Main photograph: Juan Orlando Hernández giving a speech after a demostration in the street in his support, Tegucigalpa, october 9, 2019. Photo by: Martín Cálix.

Text by: Danielle Mackey and Jennifer Avila

This article has been amended since its original publication to reflect changing news.

Tony Hernández is a former congressman from Honduras’ ruling National Party and the brother of the sitting president. Since 2004, Tony Hernández has also helped produce and distribute 220 tons of cocaine headed for the United States, according to U.S. federal prosecutors in the Southern District of New York. To do so, he used planes and helicopters, boats and a submarine. He used cocaine laboratories in Honduras and Colombia. He provided security to cartels in the form of men, often Honduran police, armed with M-16s, AK-47s and Bazookas. Sometimes Tony provided security using his government’s radar technology, which is supposed to intercept drug planes, but which Tony used for the opposite purpose: to observe the helicopters he rented to cartels as they flew their illicit cargo, to ensure no one interfered.

On Friday October 18, 2019, Tony Hernández was found guilty of large-scale drug and weapons trafficking. Years of corruption led to the trial. Some of the powerful people who allegedly enabled and collaborated with him remain in office — including, according to court testimony, his brother, President Juan Orlando Hernández.

Both Hernández brothers have denied all accusations. According to President Hernández, what was said in his brother’s trial is an act of vengeance by criminals, people quashed in the drug war his administration has conducted alongside the U.S. government.

But U.S. federal prosecutors arrested Tony, in part, because they are investigating Juan Orlando. Since 2013, the Southern District of New York has dug into a ring of people who consolidated power after a 2009 coup and may have trafficked drugs and laundered money. The investigation remains active, and, while some have been prosecuted, the others remain at the helm of the Honduran government. They include Juan Orlando and his late sister Hilda Hernández; the current Secretary of State, Ebal Díaz; and the current Minister of Defense, Julián Pacheco Tinoco. Also on the list were various members of the Rosenthal family, who owned a conglomerate called Grupo Continental, but they have been prosecuted and are now incarcerated in the U.S.

The Crimes

In September 2009, according to court documents, a shipment of Tony’s cocaine was stolen while en route to the buyer, a Mexican cartel. The cocaine was made in one of Tony’s labs in Colombia, and the shipment was in collaboration with a Honduran cartel, the Valle Valles. But a band of eight Guatemalan thieves hijacked the load as it neared the border. Tony uncovered their identities and hired a hitman to murder them.

Tony participated in at least two additional planned murders, according to trial testimony from former mayor and narcotrafficker Alexander Ardón, who turned himself in to U.S. authorities in March and is currently incarcerated. As mayor, Ardón represented the Honduran department of Copán and the same political party as the Hernández brothers, the National Party.

In his testimony, Ardón said that in 2011, Tony called the police chief of Copán, an infamous official named Juan Carlos «El Tigre» Bonilla, to order the murder of a Guatemalan narco. The police chief dutifully committed the murder, Ardón said.

In 2013, when the Honduran police arrested «Chino,» a security worker with the Cachiros cartel, Tony said that he must be killed because he was «the only one who knew everything about the helicopters» that belonged to Tony, said Ardón. He was also murdered.

The helicopter information was vital because it was Tony’s self-protection strategy. In 2012, Tony told Ardón he would run for congress and his brother Juan Orlando would try for the presidency, Ardón said in court. Tony said he would leave all involvement in narcotrafficking, with two exceptions: he’d rent out his helicopters to cartels so they could move drug shipments, and he’d provide security for those shipments. He also supplied the pilots. And since Tony had access to the Honduran government’s drug war radar technology, he provided oversight during the flights to ensure no one intercepted his helicopters. Tony charged cartels $50,000 per flight, according to Ardón.

That same year, El Chapo Guzmán shows up in the story. Ardón testified that El Chapo, the former leader of the Mexican Sinaloa cartel, asked a favor Porfirio Lobo, who was then the president of Honduras: Help in protecting the border between Honduras and Guatemala from a narco competitor. President Lobo sent two trucks of soldiers, approximately 120 men total, and they stayed for two months. They won back the border for El Chapo, Ardón said.

The following year, Ardón testified, two remarkable meetings took place. One involved Juan Orlando Hernández; the other was between El Chapo Guzmán, the Valle cartel and Tony Hernández.

At that time, Juan Orlando was congressional president and Ardón was mayor of Copán. Rumors that Ardón was a narco had evolved into news articles. Hernández met with Ardón and told him not to run for Office again. He warned him he would no longer protect him against narcotrafficking accusations. But if Ardón would «finance» the department of Copán in the next elections, bribing whoever he must, then Hernández would name Ardón’s brother Hugo as campaign coordinator. (Hugo was also a narco but wasn’t yet publicacly known for it.) In his testimony, Ardón said he did what Hernández asked: He did not run again, and he spent $1.6 million in bribes with his drug money.

Later that year, Ardón and his brother attended a group meeting with El Chapo on an estate owned by the Valle cartel in El Espíritu, Copán. Tony was also there, Ardón testified, along with another narco-mayor named Mario José Cálix and two Guatemalan brothers who worked with El Chapo.

That day, according to Ardón, El Chapo asked Tony to provide security for his cocaine shipments as they passed through Honduras. Tony responded that if his brother Juan Orlando won the presidential elections, El Chapo would have his security. El Chapo also requested a guarantee that Ardón and the Valles would not be extradited to the U.S. or prosecuted in Honduras, to which Tony responded again that he could guarantee it if Juan Orlando won.

This was the moment when El Chapo offered one million dollars for Juan Orlando’s campaign, according to Ardón. Tony said he’d consider the offer. Three days later, Tony told Ardón that Juan Orlando had authorized the bribe. In the next meeting, El Chapo handed Tony the money, partitioned into plastic-wrapped bundles of $50,000 and $100,000.

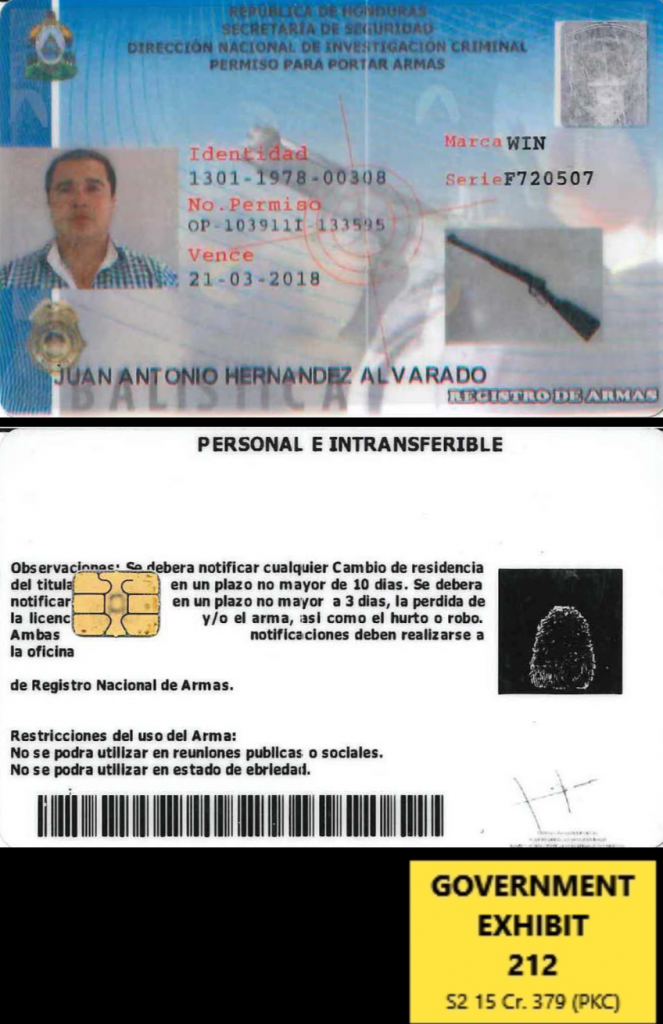

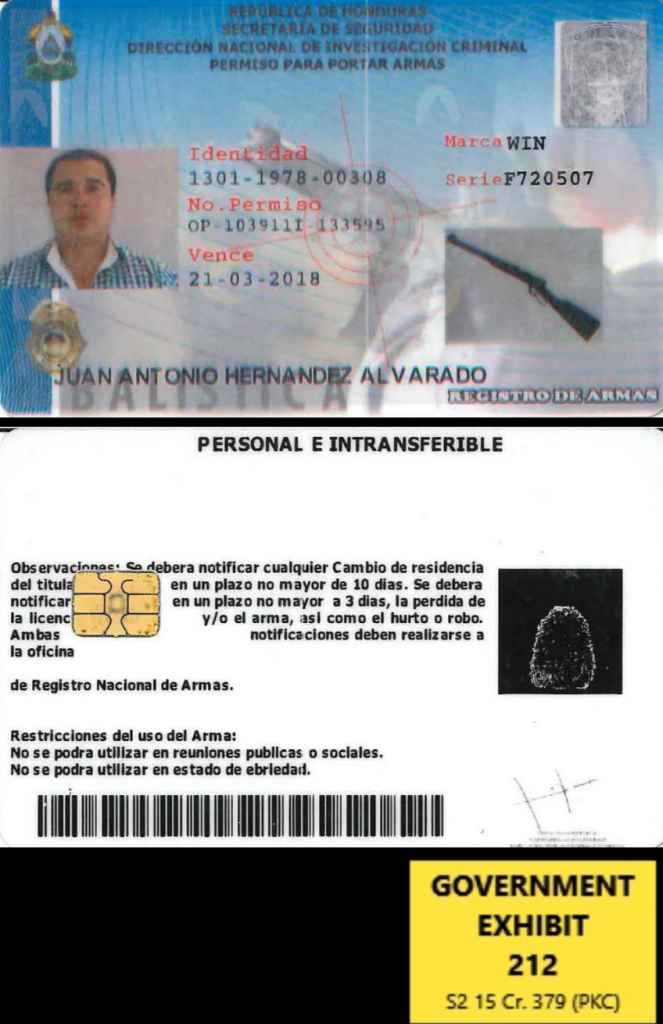

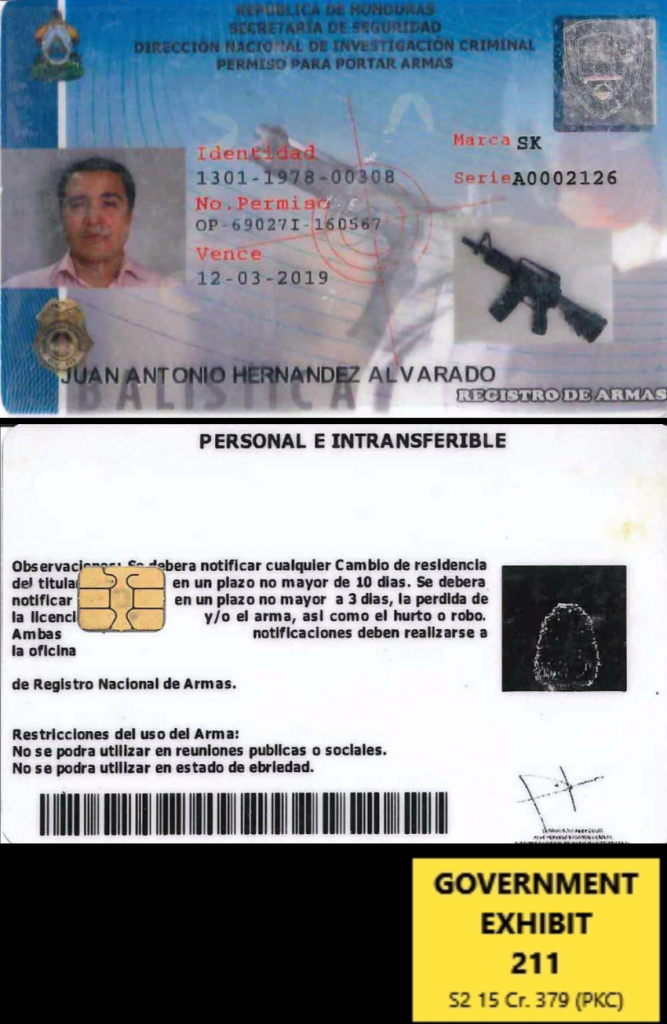

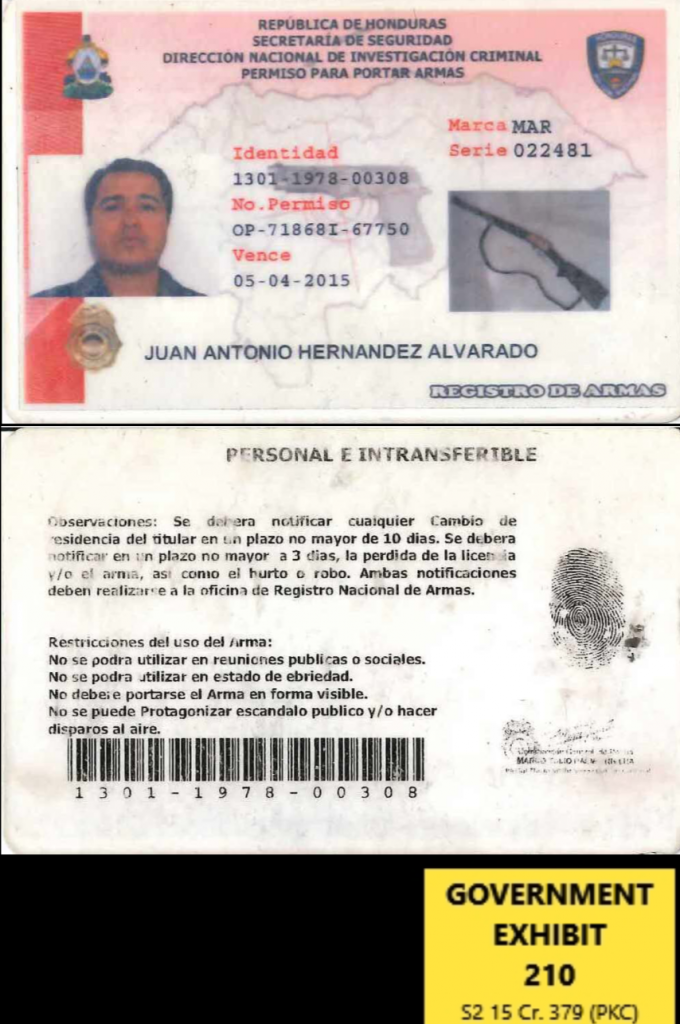

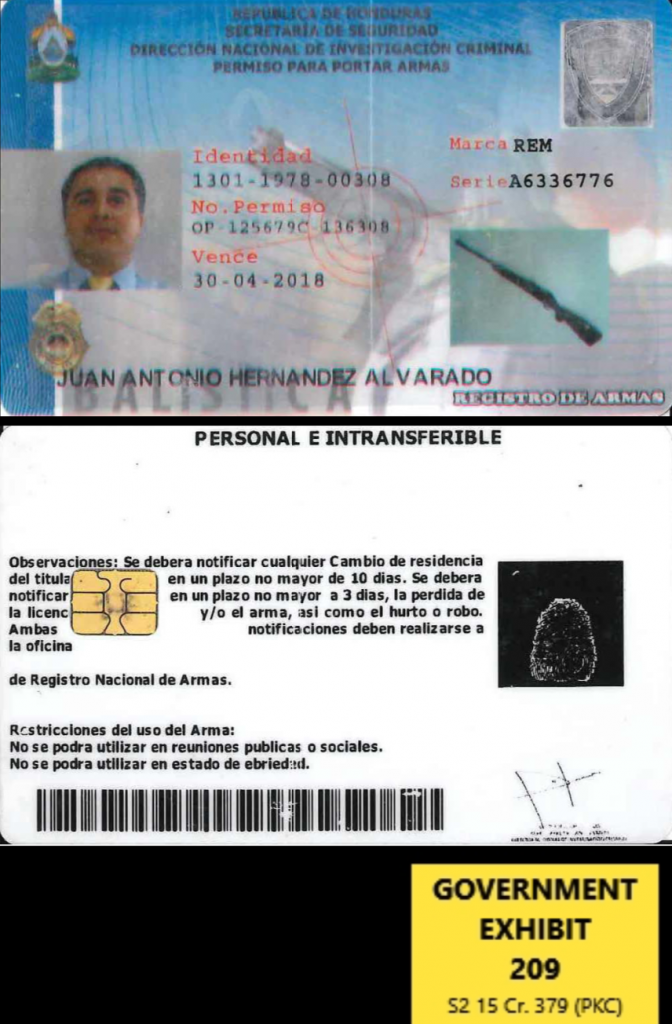

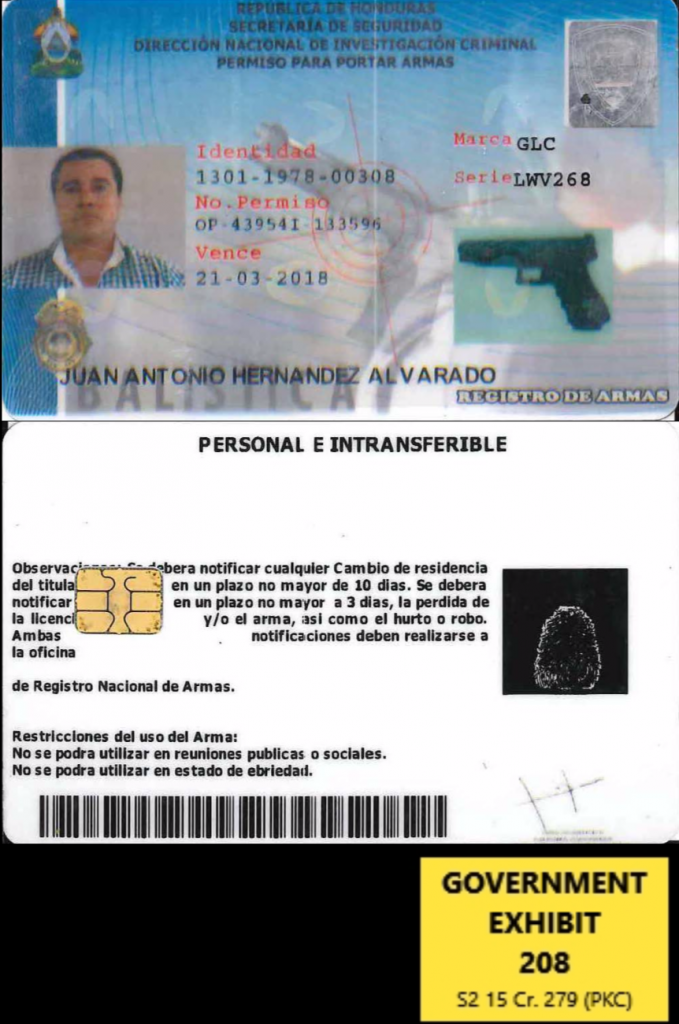

Licencias para portar armas registradas a Tony que incautaron el dia de arrestarlo.Presentadas como prueba or parte de los fiscales EEUU

Such pacts between narcos and politicians led to bloody days in Honduras.

In 2012, the country’s homicide rate was the highest in the world. A wave of children left for the United States alone and on foot, in desperate search of survival. They fled a country where nearly 3,000 kids under 17 years old were murdered between 2000 and 2014, according to the organization Casa Alianza. The children arrived to the U.S. en masse, where detention centers and courts swelled to contain them.

Meanwhile in Honduras, Tony was diverting public money into the coffers of narcotraffickers, U.S. federal prosecutors allege.

In February 2014, he met at a Denny’s restaurant with Devis Leonel Rivera Maradiaga, a leader of the Cachiros cartel, and they made a deal: Tony would pressure state agencies to pay debts to Cachiro front companies, which the cartel used to launder money, and Maradiaga would pay Tony about $50,000.

What Tony didn’t know was that the DEA had flipped Maradiaga. He covertly recorded the meeting with a wristwatch camera.

But despite the dark acts in which Tony was engaged — allegedly with the help of his brother, the president — the U.S. government remained close with the Hernández administration. Hernández pursued above-board policies that the U.S. favored, particularly anti-crime and anti-narco programs, and attempts to curb immigration. He created elite units in the police and public prosecutor’s offices with U.S. money. His administration purged the police, trained the Attorney General and conducted rural poverty reduction programs.

Those steps demonstrated values that the Obama administration shared, says Lisa Kubiske, the U.S. Ambassador to Honduras from 2011 to 2014. In an interview with Contra Corriente, Kubiske also said that she was unaware that her own government was investigating Hernández, and that this is normal.

«Juan Orlando had policies while I was there that had many aspects that were very compatible with what the U.S. hoped Honduras would achieve,» she said. «Did I know the DEA was pursuing anyone involved in narcotrafficking in general? Yes, I knew in general. Did I need to know all of the details? No,» Kubiske said. «Maybe I’ll be proven wrong, but if there had been a lot of concrete dirt on President Hernández, somebody may have said, ‘Be careful.'»

Kubiske added that although more should be known about the accusations involving the president, the current trial is not about him. «It’s not a trial about whether he accepted the money from El Chapo, although it would be important to know that. This trial is about charging Tony Hernández.»

But in the federal court in New York, Juan Orlando’s name was spoken almost as frequently as Tony’s.

Ardón testified that at least once more, in 2015, Juan Orlando summoned him to solicit campaign bribes for himself and the National Party. He promised continued protection for Ardón’s narcotrafficking.

Throughout the years, every time Ardón expressed concern to Tony about the high-level crimes in which they were engaged, Tony assured him they would not be investigated by Honduran authorities nor extradited to the United States as long as the National Party was in power.

They committed a long list of crimes behind that shield.

Tony sold weapons to the Valle cartel, and they sent them to the FARC guerrillas in Colombia, according to court documents. He also sold weapons to a witness identified only as «CW-5,» who then sold them to the Sinaloa cartel.

In October 2016, a Honduran Air Force captain named Santos Rodriguez Orellana publicacly called out Tony by publishing a photo of one of his helicopters. That same month, the DEA informed Juan Orlando that they were investigating his brother, after which Tony showed up voluntarily in Washington to give an interview. That time, the DEA let him go.

The Arrest

President Hernández enjoyed legitimacy with the Obama administration and a warm welcome by the Trump administration. On June 15, 2017, Vice President Mike Pence tweeted a photo of him smiling next to Hernández in a meeting about business and economic development.

But people isolated from the trappings of power were drowning in violence and corruption. In October 2018, the first migrant caravan left Honduras.

They walked toward the United States to solicit asylum. President Trump described them as «an invasion of our country» by «Many Gang Members» and «unknown Middle Easterners.» The Hernández administration scrambled to please the U.S., to stop migrants before they could escape their burning homeland.

In this context, the Southern District of New York issued formal charges against Tony, including an arrest warrant. On Friday, November 23, 2018 a DEA agent named Sandalio González met up with a group of U.S. agents in the Miami airport. They knew Tony had flown out of Houston that morning on American Airlines flight 1347 — a Tegucigalpa destination with a Miami layover. They settled into Terminal D, Gate 2. They waited.

They saw him walk out of the jetbridge accompanied by a colleague, with whom he had traveled to Nebraska to check out a Ford pickup for sale, and then to Houston to meet the family of a Mexican man they’d just met and whose last name he couldn’t remember, Tony would tell the DEA a few hours later.

The agents saw Tony note their presence. They saw him disappear into the bathroom. He didn’t come out, so González went in after him. Tony walked out and was approached by González’s fellow federal agents, who were from Border Patrol — the very agency that has arrested thousands of Hondurans fleeing the conditions created by people like Tony.

And that is how La Migra arrested Tony Hernández.

The interview

A couple of hours later, Agent González sat across from Tony at a small table. González wore a baseball cap and a longsleeve black shirt. Tony, in a blue polo shirt, spoke with the gravely voice of someone who woke up early and was having a bad day.

González asked Tony how long he had been a drug trafficker. Tony responded that he is not one; that yes, he knows some of them, and even some of his best friends had unfortunately fallen from the high road, but he doesn’t judge them. Yes, he said, he heard there were rumors that he was in the business, but those were pure fantasies by narcos angry with him because his brother, the president, was cooperating so effectively with the U.S. government in the drug war.

«I want to show you something,» González said to Tony.

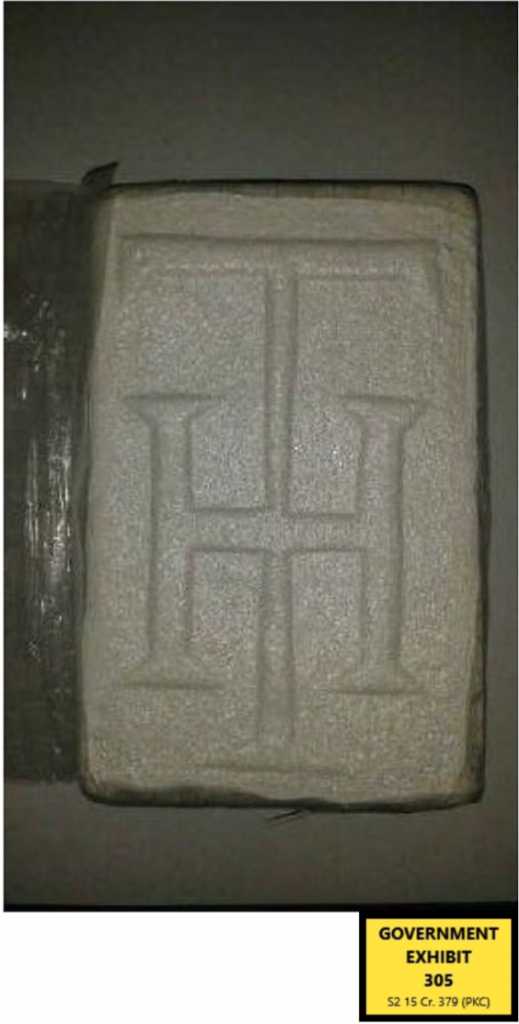

On his cell phone screen, he pulled up a photo of a white brick inscribed with the letters, «TH.»

Tony peered at it. His face didn’t change. He remained silent for a moment. Then he responded: «It’s a ‘T’ and an ‘H.'»

«Yeah, for what?» González asked calmly. Tony smiled. «Supposedly it’s ‘Tony Hernandez.'» «Supposedly?» the agent asked.

Tony shifted in his chair and let out a small laugh. He stuttered. Then he asked how they could think he would stamp his own initials on something so delicate.

But no one had said what the white brick was. And that detail caught González’s attention. «But what is this?» he asked.

Once again, Tony stuttered. «Supposedly, drugs,» he finally said.

The Analysis

Agent González and the prosecutors of the Southern District of New York represent the same U.S. government that has closely collaborated with the administration of Juan Orlando Hernández. The oddity begs an explanation.

Christopher Sabatini is a lecturer at the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University and the founder of Global Americans, a Latin America research organization. He diagnoses this as a cyclical paradox. «Imagine a president who used to be a close associate of the U.S., who was involved with narcotrafficking and then stole an election. Who am I talking about?» Sabatini asked. He wasn’t speaking of Hernández, but instead of the Panamenian dictator Manuel Noriega, who was a U.S. ally for years until the U.S. deposed him. «Noriega fell because he lived in a time when democracy was on the march, and that was his downfall. But that’s no longer the context. Democracy doesn’t matter as much,» Sabatini said.

Steven Levitzki and Daniel Ziblatt, in their book How Democracies Die, opened a debate also applicable to Honduras. «Many government efforts to subvert democracy are ‘legal,’ in the sense that they are approved by the legislature or accepted by the courts,» they wrote. «The tragic paradox of the electoral route to authoritarianism is that democracy’s assasins use the very institutions of democracy — gradually, subtly, and even legally — to kill it.» This might as faithfully describe what happened in Honduras during the coup in 2009 as the electoral crisis of 2017, in which President Hernández declared the constitution unconstitutional to enable himself to run for a second term, and was named victor after an internationally-questioned election.

But Hernández’s flagrant defiance of democracy has not eroded the legitimacy he holds in some U.S. circles, Sabatini pointed out. «JOH plays the good cop, even though he’s not,» he said. He added that the specific support from some congressional Republicans is rooted in a tendency to view everything through the lens of Venezuela. «In 2009 with the coup, Republicans and conservatives in particular doubled down on the National Party. They presented this as a black-and-white issue: Zelaya bad, in bed with narcotrafffickers, and National Party good, anti-Chavistas,» said Sabatini. «But the State Department was tracking drug flights with the arrival of Micheletti [the leader of the coup government.] They knew it, but this was such an ideological issue of pro-Chavez vs. anti-Chavez that they ignored it.»

Hernández appears to know how to pander to those Republicans. His «well-advised discourse has been that any and all protest is by ‘communists’ and ‘allies of Maduro in Venezuela,'» said Honduran security analyst Leticia Salomón, an investigator at the Centro de Documentación de Honduras (CEDOH).

For the U.S., a central contradiction is this: part of the government just proved Honduras to be under the control of narcos. Another part is supporting the ruling administration, while arguing that the Honduran immigrants who are fleeing do not qualify for asylum in the United States.

It’s an incoherence that may not matter. The priority of the Trump administration when it comes to Central America is clear, according to a U.S. congressional source not authorized to speak on the record. «If Juan Orlando promises to stop immigration, that’s all Trump wants,» the source said. «It’s also the case that Donald Trump admires dictators. Juan Orlando, of the three presidents in the Northern Triangle, is by far the most likely to do what Trump wants, which is to set up the military and shoot anyone who wants to try to leave.»

The witnesses

On October 10, 2019, in the courtroom in the Southern District of New York, Tony Hernández listens while someone else answers questions from U.S. authorities: the former Director of Operations of the Honduran police, Giovani Rodriguez, currently incarcerated in Manhattan for drug trafficking. Rodriguez is a witness in this trial, and he declares that he worked with other narcos and they all were protected by Tony.

There are no seats left in the courtroom and there are people outside who want to come in. Among them are Honduran immigrants who fled violence and corruption and have awaited truths like these for a long time. But they are recent immigrants in the United States; if they’re lucky enough to have jobs, they certainly can’t ask for an entire week off to be a spectator at a trial. So they rush here after work, and the only open seats are in the overflow room — an empty courtroom with a screen at the front that projects what’s happening in the trial, a few doors down.

Sitting in the overflow room is a middle-aged engineer who left Honduras less than one year ago, when his car was stolen by a criminal group. It turned out the robbers worked with the police, so he began to receive death threats after reporting the theft and had to escape, leaving his wife and children. He looked overwhelmed after hearing a former police official explain in detail how public security serves the will of criminal organizations. «We live in savagery,» he said.

Another immigrant witnessing the testimonies is a man whose nephew is a lieutenant assigned to the remote Mosquitia region of Honduras, a hot zone drug corridor. A friend sits beside him, a graduate of the Honduran military academy. Both are concerned by the revelations about the political elite sending the army to do narcos’ bidding. They had heard rumors, but it’s different to hear it from the mouth of cartel leaders in a U.S. courtroom. Thinking about his lieutenant nephew, the man said, «I just tell him to be careful.»

Every afternoon at around 2:00 p.m., a tall, thin teenager appears after finishing his shift as a bicycle deliveryman. One afternoon three years ago in his hometown, San Pedro Sula, he witnessed his older brother’s murder. Thieves killed his brother while trying to take the laptop he used as a medical student. The young man was standing beside his brother at the time and thus witnessed the killing, so he had to flee Honduras immediately. He is attending the trial although he sees it as a mere step toward another end. «What’s really best for the people is for Juan Orlando Hernández to fall,» he said.

On Friday, October 11, the immigrants witnessed the testimony of Devis Leonel Maradiaga. Imprisoned in the U.S. for leading the Cachiro cartel, Maradiaga took the stand and told the story of the $50,000 bribe to Tony Hernández that he filmed in Denny’s on his spy watch. He also said he bribed Juan Orlando with $250,000, and that his cartel financially supported Hernández’s campaign and the National Party.

The spectators in the court are supposed to be quiet, but sometimes they can’t contain their gasps. In the overflow room, what they’re watching on the screen is like a soap opera, a tragicomic movie about why so many people emigrate. It is the story they cannot leave behind no matter how far they flee.

It is so mind-boggling, in fact, that people in the crowd are laughing.

They laugh when Tony’s lawyer tells Maradiaga it’s obvious he has no respect for authority, and Maradiaga responds: «Both the one who offers the bribe and the one who accepts it are corrupt, sir.»

They laugh when Tony’s lawyer asks Maradiaga what he did with the millions of dollars he made through narcotrafficking, and he responds: «I already told you, sir, we invested that money in bribing the defendant [Tony], and Juan Orlando Hernández, and the army, and Tinoco Pacheco — we also bribed him, sir.» The last name referred to the sitting Minister of Security, Julián Pacheco Tinoco, and it was information that had not yet been introduced to the court, information Tony’s lawyer perhaps did not mean to introduce.

They laugh when Maradiaga explains to Tony’s lawyer how he withdrew money from his bank account when the U.S. government put him on a list of terrorists and organized criminal groups, the OFAC list, which demands immediate freezing of all accounts. «The president of Banco Continental warned me that they were going to freeze my accounts,» said Maradiaga. «I withdrew it all in cash because I was a great friend of the bank president, Jaime Rosenthal, and he gave me the cash.»

But as Maradiaga’s accusations continue, laughter fades. There is an occasional whispered, «Wow.» People slowly shake their heads. Silence rolls over the spectators like fog.

Maradiaga is just one more witness who, by the end of the trial, will have declared under oath that Honduras is a place where presidents solicit millionaire bribes from narcotraffickers and promise not to prosecute them. That Honduras is a place where the political elite perverts democracy and sends the police and army to shield narcos and execute their rivals. That Honduras is trapped in a criminal age.

A university student returns a tear gas bomb launched by the National Police during a confrontation in Ciudad Universitaria, Tegucigalpa, October 7, 2019. Photo: Martín Cálix.

Post Script

Seven months before the trial began, on March 1, 2019, the DEA tweeted photos of one of President Hernández’s visits to Washington. It celebrated the «continued partnership» between the agency and the president, through which they «work jointly to combat drug trafficking.»

There was a cascade of incredulous responses: «Is this a joke?» «This is a parallel universe!» «You should have captured him then and there.» Then, this observation: «Typical work by the DEA, working with some narcos to capture others. But sooner or later this one will fall.»

On the last day of the second week of the trial against Tony Hernández, when proceedings had ended and the crowd had exited, the teenager from San Pedro Sula stood outside the Southern District of New York. He waved goodbye, gestured toward the courthouse and said, «See you again when they bring Juan Orlando.»