Photos by Martín Cálix

Almost a year after the country declared a national state of emergency due to the pandemic and in the midst of a new surge in COVID-19 cases, only two of the seven mobile hospitals procured by the government are up and running, and these are only operating at a reduced capacity. The Superior Court of Audit has sent two audit reports to the Ministry of Justice on improper procurements made by Invest-h and COPECO related to the public health crisis.

The Honduran Cardiopulmonary Institute, also known as the Thorax Hospital, had exceeded its capacity in June and July 2020, and no longer had any ventilators for seriously ill COVID-19 patients. The doctors then decided to use two Breas Vivo ventilators purchased by COPECO (Comisión Permanente de Contingencias), the Honduran emergency management agency. They stopped working after only five days of use and the two patients connected to these ventilators died.

The ventilators were the first pandemic-related purchases made by COPECO. Tasked with managing the public health crisis, COPECO spent US$2.28 million on 90 devices for treating patients with severe coughs (Phillips CoughAssist T70), 90 Trilogy Evo portable ventilators, and 40 Breas Vivo 65 ventilators. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued several adverse event reports for these devices, most recently in February 2020.

Suyapa Sosa, the Thorax Hospital’s head of pulmonology, told Contracorriente that in January 2020, a multidisciplinary team from the hospital sent the Ministry of Public Health specifications for equipment needed to address the emergency. “We didn’t want what always happens౼ they buy disposable equipment without warranties. That’s just plain theft,” said Sosa.

But the ventilators didn’t work and were missing some components, so the government had to pay an additional 4.5 million lempiras (US$184,083) for the missing components. The purchase was made through Invest-h (Inversión Estratégica de Honduras), a government agency for planning and executing strategic development projects. Yet when the additional components arrived, the ventilators still didn’t work.

“A Vivo 50 ventilator arrived with a damaged screen and another Vivo 65 unit has an internal leak. This hasn’t been reported to the supplier since we don’t know who provides warranties for the equipment or if it’s even covered under a warranty. Thirteen of these ventilators are sitting unused in storage,” stated a document issued by the staff at Leonardo Martinez Hospital in San Pedro Sula.

The deaths attributed to ventilator failures were documented in a Superior Court of Audit (Tribunal Superior de Cuentas – TSC) report on COPECO procurements. Authored by cardiologist Dr. Luis Fernandez, the report indicates that after the two patient deaths, he “strongly recommended against using these ventilators. This recommendation is also based on FDA warnings about the device’s lack of safety alerts during potential malfunctions.”

The ventilator purchases were authorized by the former head of COPECO, Gabriel Rubí, who was fired in April 2020 due to his role in these questionable purchases. Rubí told the TSC that quotes for the ventilators were obtained by the Honduran embassy in the United States, and that the minister of finance at the time, Rocío Tabora, asked him to fund the purchases due to the ventilator shortages in the marketplace. However, the TSC report notes that Rubí did not provide any documentation to support this claim.

After being dismissed from COPECO, Rubí returned to his previous position as a National Party congressional representative for the department of Yoro. Rubí is running again for Congress in the next election and has joined Nasry Asfura’s faction in the National Party. Asfura is the current mayor of Tegucigalpa and has been indicted for allegedly embezzling 28 million lempiras from the mayor’s office.

The TSC report details a number of irregularities in the ventilator procurement process, including an inconsistency in the ventilator invoices issued by Partners Medical Supplies, Inc. (dba City StairLift). Payment for the ventilators was made to a different company, International Medical Equipment, LLC. In addition, the website and email addresses indicated on the invoice (www.partnersmedical supplies.com, info@partnersmedicalsupplies.com) are non-functional.

Another irregularity is that COPECO never verified whether the supplier was eligible to enter into contracts with the Honduran government, nor whether it was legally incorporated in its country of origin. Lastly, COPECO did not obtain a notarized statement from the supplier affirming that there were no disqualifying conditions that could result in a contract annulment.

Sosa said there was pressure to use the faulty ventilators, but they refused due to their bad experiences with the equipment, particularly the two deaths.

The minister of public health, Alba Consuelo Flores, informed the news media that her agency was investigating the deaths to “analyze their causes, to determine whether the equipment was actually a factor, and why the equipment was not tested prior to use.”

COPECO also purchased airway suctioning equipment that isn’t needed for treating COVID-19 patients. This equipment cost more than 15 million lempiras (USD$702,000) and according to the TSC report, is now stored in the Ministry of Public Health’s national drug warehouse.

As for the malfunctioning ventilators, Sosa said, “I think they’re in our [Thorax Hospital] warehouse, although I know we’ve asked to return them. We don’t want anything to do with these useless ventilators.”

While these are the first two deaths directly attributed to questionable government purchases during the public health emergency, it was only the first of many poor decisions related to the pandemic.

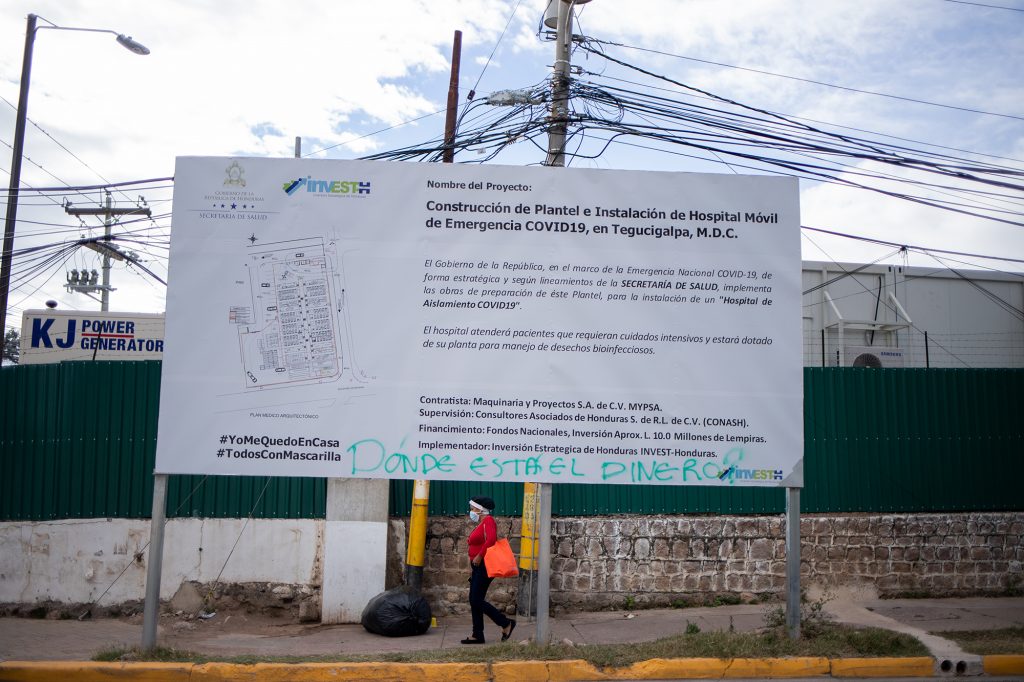

The endless wait for the mobile hospitals

A few weeks after the national state of emergency was declared, there were concerns that the country’s hospitals could be crushed under all the COVID-19 cases. Consequently, Invest-h initiated the purchase of seven mobile hospitals with medical waste treatment capabilities and biomedical and biosecurity equipment. The contract included transportation of the hospitals to Honduras, installation by specialists, and hospital site preparation. All this would cost 1.74 billion lempiras (US$69.6 million).

In an interview with Contracorriente, German Perez, a representative of the National Association of Industrialists (Asociación Nacional de Industriales – ANDI) said, “We could have built a real hospital with all the money spent so far and that continues to be spent [on the mobile hospitals]. We could have met all the specifications [for the hospital] in the same amount of time or maybe a little more, but at least we’d have a new hospital to use once the pandemic is over.”

Gustavo Irías, executive director of the Center for Democratic Studies (Centro de Estudio para la Democracia – CESPAD), said that corruption in the midst of an economic crisis is an indicator of the difficult years ahead for Honduras. “The country is collapsing, its imports and exports have dropped and, paradoxically, we’re experiencing an overvalued lempira. Then, despite the millions spent on measures to combat the pandemic, the country’s hospitals have collapsed,” said Irías

The first two mobile hospitals purchased by Invest-h arrived in Honduras on July 9, 2020, and the remaining three arrived in November, despite promises of delivery between May and June. The San Pedro Sula mobile hospital began operating in October 2020, and the Tegucigalpa hospital began operating on January 29, 2021.

The mobile hospital in Tegucigalpa was delivered six months before it was finally up and running. According to a TV newscast, the hospital modules had 56 defects, 90% of which were rectified. The Tegucigalpa mobile hospital coordinates patient care with the University Teaching Hospital (Hospital Escuela Universitario – HEU), and although its initial maximum capacity was estimated at 91 patients, this was reduced to 64 patients. It has 16 intensive care beds, 16 intermediate care beds, and 32 for basic care with vital sign monitoring.

At the end of January, the death of one the first two patients transferred from the HEU to the mobile hospital was reported. The patient was sent back to the HEU because the mobile hospital does not have a full-fledged intensive care unit (ICU).

“There are modules of the mobile hospital designated for intensive care, but as I said before, it was a titanic task to get this hospital functioning for basic and intermediate care patients. It will take much more time to enable the ICU modules,” said the HEU’s deputy director, Franklin Gómez, to several media outlets.

Sinely Diaz, a relative of the deceased patient, stated in the Hoy Mismo newscast that she was never informed of her uncle’s transfer to the mobile hospital and subsequent return to the HEU. “No one knows much about these mobile hospitals. Someone should tell us whether they’re really prepared to receive seriously ill patients. Someone should be responsible for accepting patient transfers, for verifying that they’re in stable condition and for keeping them stable. Not make them worse like what happened to my uncle,” said Diaz, adding that her uncle died an hour after being readmitted to the HEU.

One of the obstacles that delayed the opening of the mobile hospital in Tegucigalpa was that no one realized that it would need its own operating budget. However, Fredy Guillén, the Vice-Minister of Public Health, said that 24-25 million lempiras had already been transferred to the HEU budget, which is the estimated monthly operating budget for the mobile hospital.

In a statement to the media, Guillen said that the mobile hospitals, “…have been heavily criticized by political partisans. I’m not going to participate in that controversy because that’s not my strength. I prefer to work rather than talk. But it’s important to say that the very trustworthy HEU team is behind these hospitals, which will be a great asset for the Honduran people.”

Contracorriente tried to contact Rony Antúnez for an interview, but he did not respond to our requests. Antúnez is in charge of the mobile hospital in Tegucigalpa, and previously was responsible for coordinating the Government Civic Center’s triage unit. In other statements to the media, Antúnez said that the mobile hospital will provide 24-hour care and will have 275 employees. “Now’s the time to look ahead and get the hospital up and running as soon as possible. Let’s not dwell on how long it took to get here,” he said.

However, the TSC audit claims that the Invest-h contract with the mobile hospital supplier did not include any stipulations about delivery timelines; a deficiency that ultimately harmed the country’s health care system, since the acquisition of these hospitals was intended to “care for the country’s COVID-19 patients and alleviate other facilities in the national public health system, which at times have been heavily strained due to their inadequate capacity for this type of patient.”

One of the most heavily criticized decisions made by Marco Bográn, the former Invest-h director, is that he authorized full payment for the seven mobile hospitals before a contract was in place with appropriate quality assurance provisions and penalties for late delivery.

According to the TSC, the Honduran government should have imposed fines of more than six million lempiras (US$281,115) for the late delivery of the first few mobile hospitals alone.

The delays prompted Invest-h to send emails to Axel López, the representative for Elmed Medical Systems, the intermediary through which the hospitals were purchased, asking him for an explanation of the delays. In his reply, López placed the blame on pandemic restrictions in Turkey, the country where the hospitals were being assembled. However, no formal request for an extension of the delivery time was ever received.

The TSC sent an official letter through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to authorities in Turkey to obtain more information on the progress of the mobile hospitals. The Turkish embassy in Guatemala responded, “There are no restrictions on the production or transportation by land, air or sea of commercial goods for the industrial sector, either domestically or internationally.”

Once the hospitals arrived months after the promised delivery date, the expert engineers that the manufacturer agreed to provide never arrived to assist the specialized teams in the local installation. The mobile hospitals were not installed within a week of delivery as promised, and 61 ventilator units are still missing.

Furthermore, the bid submitted by Elmed Medical Systems (dba Hospitalesmoviles.com) included photographs of mobile hospitals installed by other Turkish companies౼ Turmaks Healthcare & Mobile Solutions and SDI Global LLC. Elmed’s bid also included images of the technical specifications for hospital modules installed by one of these other companies.

“[Elmed Medical Systems] did not have any demonstrable experience in this area, so they resorted to the improper use of information belonging to other companies in order to win a contract with the Honduran government. Moreover, no evidence was presented that demonstrates that patents pertaining to the mobile hospitals proposed in its [Elmed’s] bid are registered to them.”

An NCAGE code (for NATO registered suppliers) “TH663” appears on Elmed Medical Systems’ invoice. According to the verification tool on the NATO Support and Procurement Agency website, this code belongs to SDI Global LLC.

Recommended reading (in Spanish): Invest-h purchase of mobile hospitals was a scam

Another Invest-h purchase cited in the TSC audit report is the procurement of 350 ventilators from Dimex Médica, a Honduran medical supply company, which was paid 80% of the contract value in advance. Invest-h also purchased 200 ventilators from Grupo Técnico, which was paid 75% of the contract value in advance. Invest-h disbursed more than 218 million lempiras (US$8.76 million) for both purchases.

Dimex Médica was supposed to begin delivering the ventilators last August, but the TSC audit report indicates that they still have not been delivered. Dimex is now unable to deliver all the ventilators stipulated in the contract and will only deliver products corresponding to the total amount paid in advance. The TSC report also says that the government should fine this supplier more than 5 million lempiras (US$209,168) for the delivery delays.

As for Grupo Técnico, the company has stated that it could not deliver the ventilators on time “due to force majeure.” However, this supplier has also failed to provide the manufacturer’s bills of lading, so a cancellation of the entire order is being considered.

Invest-h also bought 250,000 COVID-19 tests costing more than 48 million lempiras (US$1.9 million), which were damaged in transit due to elevated temperatures. So far, Invest-h has not required the supplier to replace these damaged tests. The purchases were made from Bioneer, a South Korean company, but there is no evidence that any bids were obtained from other suppliers. There is also no evidence that an expert was consulted regarding this purchase, so Invest-h made the mistake of acquiring test kits that did not contain all the components needed for testing, such as swabs, tubes, and transport media.

Invest-h paid 100% of the test kit cost in advance without securing any basic guarantees from the supplier. Invest-h submitted claims to the supplier for the replacement of 150,000 tests, but Bioneer responded with a counteroffer to replace them at a cost of $2 each, plus shipping and insurance.

Recommended reading (in Spanish): Another US$2 million in questionable purchases by Invest-h for COVID tests and processing equipment

Invest-h made another questionable purchase of 150,000 KN95 masks from Access Telecom for a unit price of 116.32 lempiras (US$4.64). Contracorriente found that this company is linked to Arturo Osmond Maduro Zelaya, a nephew of former President Ricardo Maduro, although former Invest-h director Marco Bográn said that he had mistakenly placed Maduro’s name on the purchase order. The TSC report also revealed that Access Telecom’s bid had the highest price of all the companies competing to supply these masks.

Recommended reading (in Spanish): The fortunate few benefitting from the pandemic

A flawed justice system

Although the TSC has asked the Ministry of Justice to take action, as of October 2020 it has only formally pressed two charges against Marco Bográn and none against Gabriel Rubí.

Bográn was remanded to custody for embezzlement of public funds and violation of the duties of public officials. These charges do not pertain to the procurement processes described above, but for paying Invest-h employee housing expenses and for awarding a contract to his uncle, Napoleón Corrales, for construction of the mobile hospital in Santa Rosa de Copán. Two days after his detention, the presiding judge ordered his release and imposed alternative measures.

Irías says, “There is a network of corruption that has shielded itself [from prosecution] very well. For example, the corruption cases investigated by the Mission to Support the Fight against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (Misión de Apoyo Contra la Corrupción y la Impunidad en Honduras – MACCIH) were effectively countered by a series of impunity agreements that had the sole purpose of preventing the criminal prosecution of senior government officials. We also know that the ruling party has a track record of misusing public funds to finance political campaigns in election years like this one.”

In four of the 13 corruption cases investigated by the now-defunct MACCIH, at least half of the people implicated in acts of corruption were acquitted. One of these cases involved a network that embezzled public funds to finance political campaigns. In addition, many of the legal regulations that were modified to benefit public officials accused of corruption remain effective today.

“The pandemic and the recent floods have provided a favorable environment for corruption because impunity is becoming even more entrenched, and efforts to reverse this trend have failed. Furthermore, many sectors of the Honduran economy have collapsed, which will take many years to recover. There are no prospects for a short-term recovery for our country,” said Irías.