It’s been eight months since Ana Hernández was found dead at her home, south of Tegucigalpa, the capital of Honduras. Her family still doesn’t know the results of the autopsy, which would determine if Ana was a victim of femicide. Recently, her father was issued a certificate to claim the corpse and a crime report by the District Attorney’s Office, but the results of the autopsy were not revealed. For Ana’s family this is another sign of the impunity that surrounds not just her case, but many others in Honduras.

Text: Vienna Herrera

Photography: Fernando Destephen and Jorge Cabrera

Translation: José Rivera

English edit: Amy Patricia Morales

Cover: Generated with Canva AI

Ángel Hernández paid the District Attorney’s Office 8$ for two reports to have answers about her daughter’s autopsy. The reports did not reveal the cause of death. He leaves the folder that contains the reports on the table and walks away with a feeling of indignation. He’s reluctant to accept the only and insufficient explanation provided by the Attorney General’s Office about the violent death of his daughter, Ana Hernández, on March 19, 2023.

“I know that the case will not be solved,” Don Ángel said as he sat on a white plastic chair in his living room. I had to wait for almost a month to get those papers: a certificate to claim the corpse which states that the cause of death will be determined upon “conclusion of an investigation,” and a report issued by the General Secretariat of the Attorney General’s Office (Secretaría General del Ministerio Público) which—in addition to the same information—states that “it’s issued exclusively to request political asylum.” But Don Ángel is not seeking asylum and is not planning to. However, those words seem like a warning or an omen.

Ana was a 32 year-old woman who worked at the National Institute of Investigation and Intelligence (Dirección Nacional de Investigación e Inteligencia – DNII). She was found dead at her home, and authorities initially considered her partner—Franco Méndez, artillery officer—the main suspect. He said that Ana had killed herself and even though he was detained for illegal possession of weapons, authorities released him nine days later. Ammunition, cartridge cases, six grenades and rifle and handgun magazines (all prohibited outside of military facilities) were found at his home.

Ana’s death occurred in the midst of a national strike by the Attorney General’s Office and judicial morgues. During this time, autopsies were not performed on dozens of victims who suffered violent deaths. Ana’s family was desperate and occupied the country’s main highway as a sign of protest. As a result, an autopsy was performed, but at the Faculty of Medicine of the National Autonomous University of Honduras and not in Forensic Medicine.

Don Ángel is concerned. People involved in the case have told him to stop inquiring about his daughter’s death and to stop demanding justice. After not receiving any news on the case for a while, he managed to meet with the prosecutor leading the case and the person responsible for performing Ana’s autopsy in Forensic Medicine. In early November, the prosecutor told him that Ana had been alive for 20 minutes, which explains why there was blood in the kitchen, but she was found in her bedroom.

Ana’s family did not find any traces of blood between the kitchen and her bedroom; they did find blood on the kitchen sink when they were cleaning the house. According to her family, Ana was found with a gun in a position which does not match a suicide, the alleged cause of death mentioned by Franco. Franco acted strangely on the day when Ana died; he called Ana’s father and told him that he had a fight with her, and she allegedly threatened to kill herself. He later said that he was far from the house, but acquaintances of Ana deny that claim. Moreover, Franco told the police that they did not live together, but his belongings were found at the house.

“The District Attorney’s Office cannot explain how my daughter shot herself, went to the kitchen, cleaned the blood on the floor and then died in her room,” Don Ángel said. When Ana’s sister asked the prosecutor to clarify how that version is possible, she got upset and told them that she’s just reading what she saw on the investigation report and that she was recently assigned to the case.

Don Ángel is doubtful about the investigation report that the Police Unit of Investigations (Dirección Policial de Investigaciones – DPI) issued to the Attorney General’s Office. A source within the unit told Contracorriente that the hypothesis of a suicide was ruled out. Ana’s father says the police did not analyze the data on her phone, but asked him if he knew the access code or if he knew someone who could hack it.

At the end of the meeting, the prosecutor offered Don Ángel a report, “That’s all we can give you,” she said. He accepted the offer, hoping that they would provide a clearer explanation about his daughter’s death. Weeks later, when the report was ready, he noticed it stated that it was issued to request political asylum. Don Ángel doesn’t know what happened to Ana’s partner, but a military officer said he was discharged. Contracorriente tried to verify this information, but no member of the Armed Forces came forward, not even anonymously.

Don Ángel says that nothing will bring his daughter back and he has to come to terms with her passing. Ana was about to finish paying off the mortgage on her house, and now the bank is waiting for the autopsy to proceed with the insurance claim. In addition, Don Ángel says that benefits from Instituto de Previsión Militar, where Ana contributed since she began working at DNII ten years ago, have been suspended. DNII has not expressed their condolences to Ana’s family and has not reached out to them to ensure that their rights are protected.

Furthermore, the medical examiner who performed the autopsy told Don Ángel that they’re evaluating the possibility that Ana’s death was an accident. One hypothesis suggests that someone had made a shot into the air and went through the roof and hit Ana’s head. According to the medical examiner, she died in a matter of 20 to 30 seconds, which contradicts the prosecutor’s hypothesis that she died after 20 minutes. Don Ángel could not understand many technical terms the medical examiner mentioned, but he said that they will send the evidence to other countries to determine if the hypothesis is feasible.

The medical examiner told Don Ángel that he performed the autopsy on Keyla Martínez, a nursing student who was a victim of femicide in a police cell in 2021. Don Ángel lost hope when he heard those words, “that’s why I think my daughter’s death will remain in impunity. Cases are never solved.”

Keyla’s case is similar to Ana’s. Preliminary police reports suggested that Keyla had also killed herself. The details of her death are also not clear to her family. Although the only person accused of the crime—Jarol Perdomo, a police officer—was put on trial, none of the witnesses came forward, and Perdomo never testified.

Keyla’s family is dissatisfied with both the trial proceedings and the court’s decision that found the officer guilty of involuntary manslaughter. This offense is outlined in the new Penal Code, referring to a situation where a person causes the death of another due to gross or ordinary negligence. According to our current legal framework, the penalty for this crime ranges from one to three years for minor cases and three to seven years for serious ones.

This resolution came about after the Supreme Court (Corte Suprema de Justicia) rejected an appeal to a writ of amparo submitted by the family. The family sought a sentence for aggravated femicide, a crime punishable by 25 to 30 years in prison, rather than homicide, for which the defense had requested a sentence of 15 to 20 years.

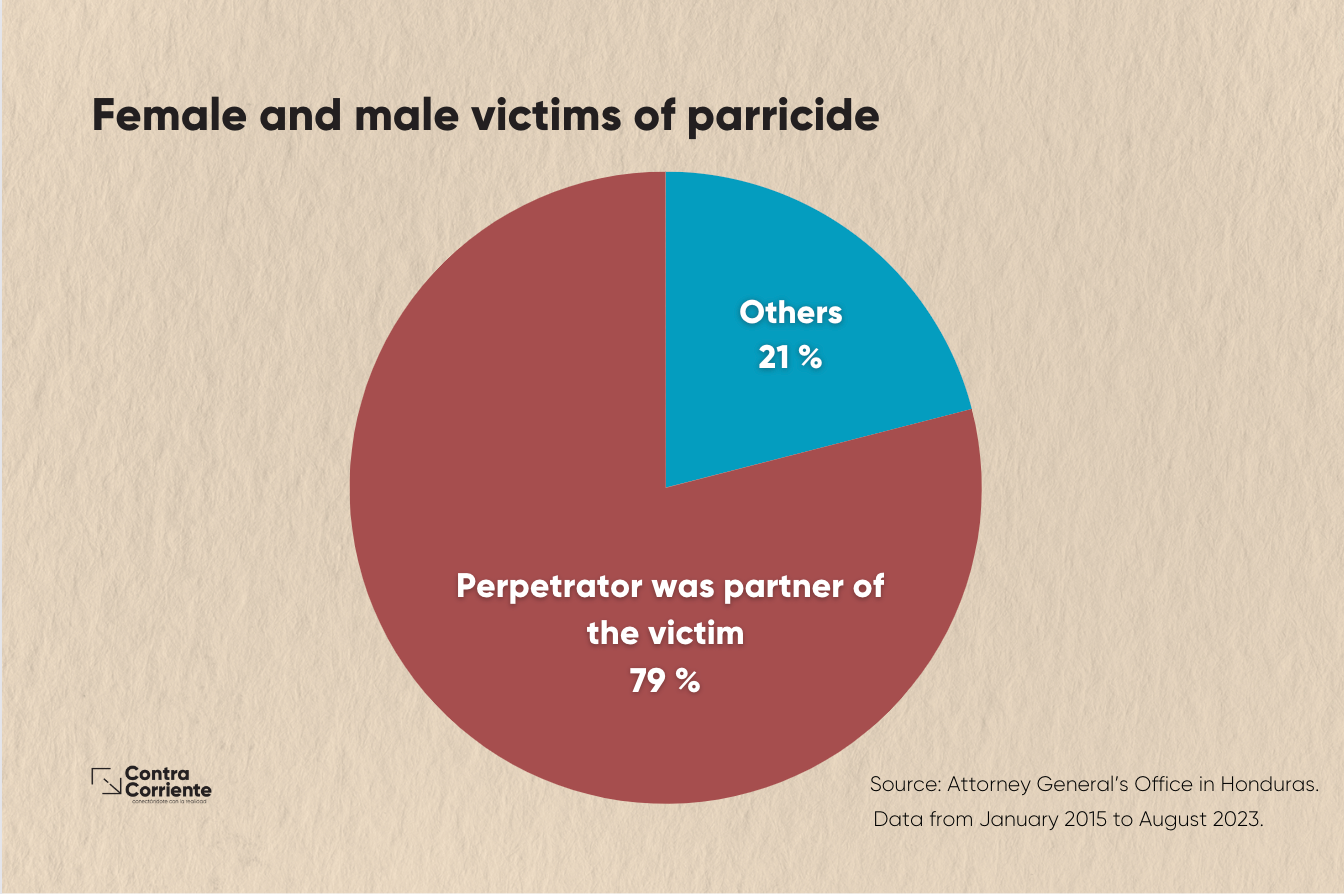

Wrong categorization of crimes is not unusual in the Honduran legal system. From January 2015 to August 2023, the Attorney General’s Office registered 21 parricides—from the 100 cases that occurred during that time—in which the suspect had a relationship with the female victims. However, Article 208 of the Penal Code stipulates that the crime is considered aggravated murder if the perpetrator “was the victim’s partner.”

The feminist attorney Karol Bobadilla says that the 2013 amendment of the Penal Code to recognize femicide as a crime hasn’t had any impact on the lives of women or the violence they face. “Public officials have no awareness or understanding of what constitutes a femicide and the importance of the Penal Code to identify the types of human rights violations that women suffer.”

Moreover, Bobadilla said that erroneous hypotheses and the wrongful categorization of violent deaths as suicide are indications that there’s a pattern in public institutions. “It’s a pattern that violates international standards, which establish that due to the highly violent environment surrounding women, all cases of seemingly violent or non-violent deaths must be investigated as femicides.”

According to the Gender Equality Observatory for Latin America and the Caribbean, Honduras, with a rate of 6 per 100,000 women, is the Latin American country with the highest rate of femicides and violent female deaths. The Dominican Republic has the second highest femicide rate, 2.9.

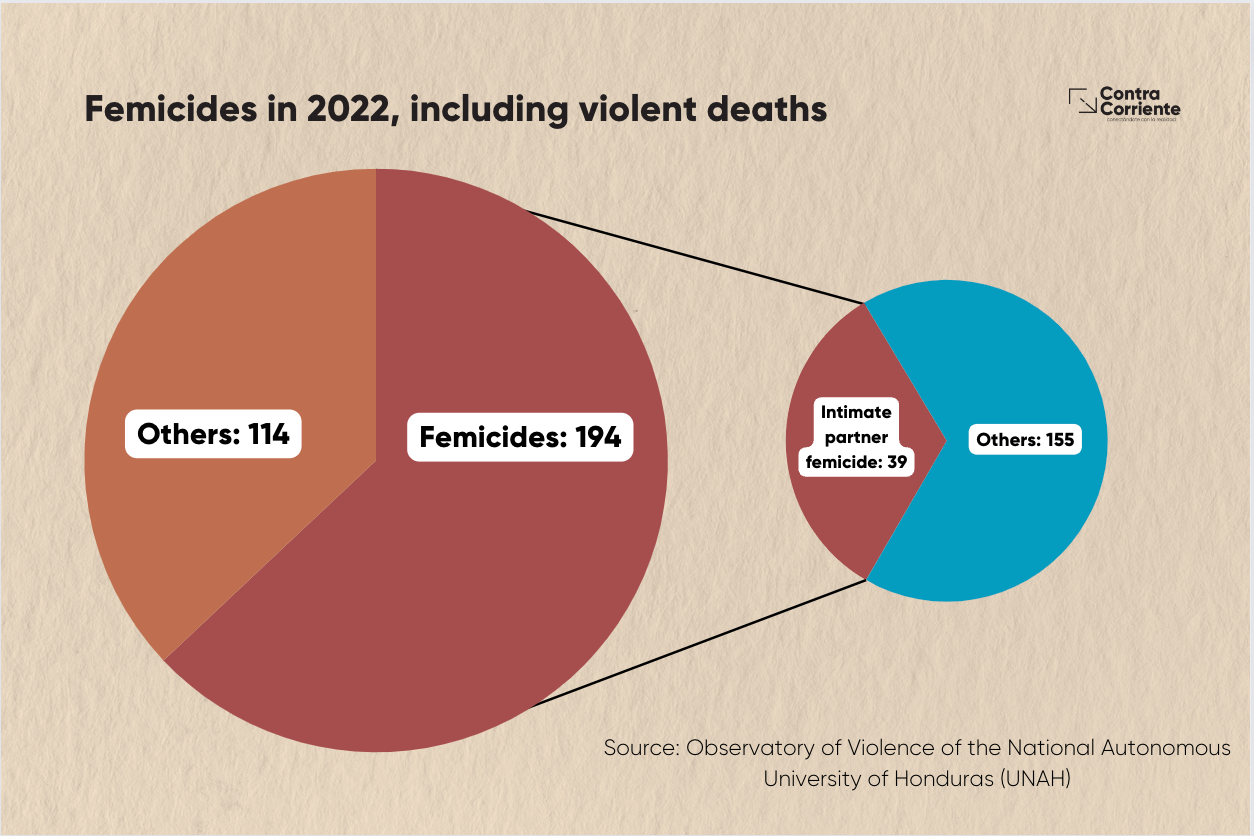

The Violence Observatory at the National Autonomous University of Honduras (OV-UNAH) registered at least 7,095 violent female deaths and femicides between 2005 and 2022. Most of the women were between the ages of 30 and 34. In Honduras, femicides constitute the most common cause of death. OV-UNAH carried out a case-by-case study of data from 2022 and determined that of the 308 registered cases, 194 were femicides and the rest were inconclusive violent female deaths or murders. Of the 194 femicides, 39 cases were intimate femicides, i.e., the victim was murdered by her current or former partner.

Migdonia Ayestas, coordinator at OV-UNAH, expressed how concerning those numbers are. “Men think they own women and (…) as a partner, former partner or suitor that they have the right to take the life of a woman. We need to make progress in our commitment to prevent crimes against women,” she said.

The Center for Women’s Rights (Centro de Derechos de Mujeres – CDM) denounced that although 1,104 femicides and violent female deaths were registered by the Attorney General’s Office during the last three years, only 29 cases led to a conviction.

Don Ángel has been told that Johel Zelaya, acting attorney general, is the only person who can help him solve his daughter’s case, but he hasn’t met with him yet. Contracorriente tried to contact Zelaya and Mario Morazán, deputy attorney general, to know more about Ana’s case and how they plan to address femicides and violence against women from the judicial branch, but by the time this piece was published, they had not responded to our interview requests.

Alice Shackelford, United Nations Resident Coordinator in Honduras, stressed the importance of institutions responsible for women’s justice. “The acting attorney general and the deputy attorney general should work hard to address this issue while keeping in mind its historical context, and the Supreme Court should inform the population about the steps they’re taking to reduce cases of violence against women,” she said.

Doris García, minister at Secretaría de Asuntos de la Mujer, an organization committed to promoting and protecting women’s rights, said that for almost two years she tried to meet with Oscar Chinchilla, former attorney general, but he would never agree to a meeting. García affirmed that the acting attorney general has met with her to listen to her demands, “The Attorney General’s Office is responsible for investigating violent female deaths and for establishing and strengthening units that assist in the investigations. To the degree that those efforts are successful, perpetrators will think twice about murdering a woman,” she said.

Bobadilla says it’s concerning that the institutions responsible for guaranteeing justice in Honduras, the National Police, the Attorney General’s Office and the Supreme Court have no perspective of gender. “More than half of the population cannot turn to these institutions to seek justice.”

Although Don Ángel says that no one will be held accountable for his daughter’s murder, he refuses to lose hope. He keeps Ana’s house intact with evidence that could prove Ana was a victim of femicide; “in case the prosecutors want to see it,” he said.

Don Ángel saw Julissa Villanueva, security vice-minister, on one of the most popular Honduran television programs talking about a possible case of domestic violence. He sighs and says with a tone that reveals resignation and sadness, “I wish those responsible for ensuring justice would go on one of those programs to talk about my daughter’s autopsy. I wish they did it for Ana and all the other victims.”