One year and a half after Honduras approved the Comprehensive Care Protocol for Sexual Violence Victims and Survivors, Doctors Without Borders denounced that the protocol has not been implemented. There are no health facilities or clear mechanisms to avoid revictimization. Medical personnel in several parts of the country don’t know how to provide post-exposure prophylaxis, and the population doesn’t know where to seek help in case of a medical emergency.

Text: Vienna Herrera

Photography: Fernando Destephen

Although post-exposure prophylaxis has been available to victims of sexual violence in Honduras since December of 2022, adequate medical treatment has not been provided as there are no health facilities and the population doesn’t know where to seek help, according to Doctors Without Borders (Médecins Sans Frontières – MSF), an organization that provides comprehensive medical assistance to victims of sexual violence in Tegucigalpa, San Pedro Sula and Chamelecón.

Last year, MSF assisted 719 victims and survivors of sexual violence, but only 12 percent of them sought assistance within 72 hours of the event; of these cases, only 45 women took the emergency contraceptive pill (píldora anticonceptiva de emergencia – PAE).

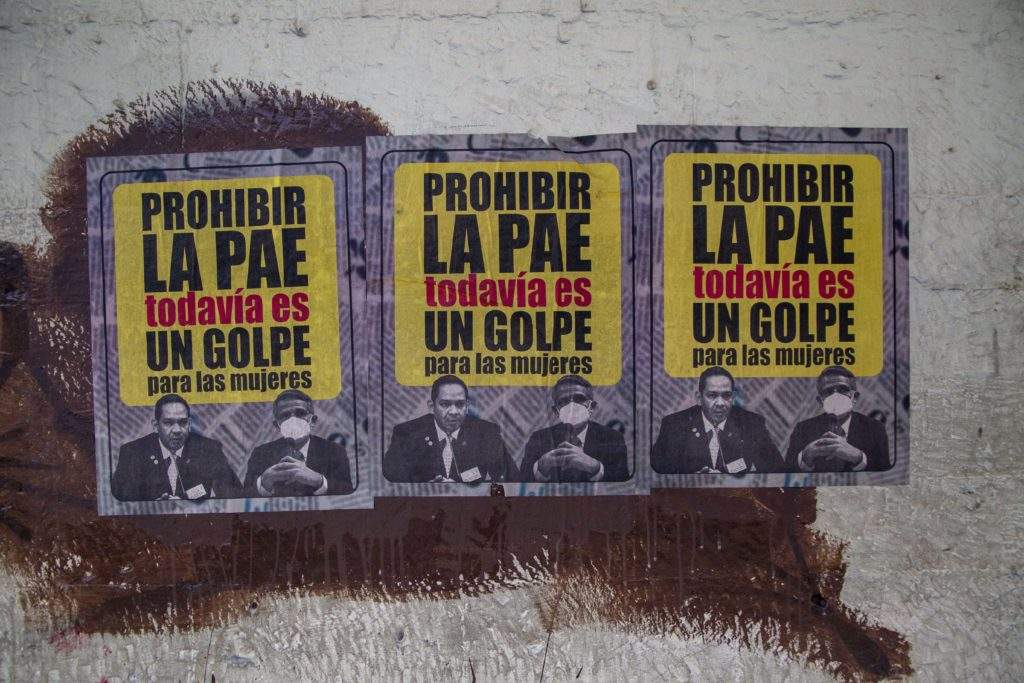

The protocol was established in 2016, but its approval was delayed since it allows the use of the emergency contraceptive pill, which was banned from 2009 (following the coup that ousted President Manuel Zelaya) to March 2023, when President Castro lifted the ban.

Contracorriente talked to two members of MSF: Laura Fonseca, humanitarian affairs officer, and Joaquim Guinard, coordinator in San Pedro Sula and Choloma, who explained the present situation of sexual violence in Honduras, the cases they see in their clinics, the most important steps to implement the protocol, and the importance of receiving care within 120 hours of the event to avoid pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases.

Contracorriente (CC): What is the present situation of the Comprehensive Care Protocol for Sexual Violence Victims and Survivors, which, according to MSF, has not been implemented?

Joaquim Guinard (JG): After the protocol’s approval in December of 2022, which was published in the official gazette, there was a campaign to inform the population. MSF continues to assist people wherever that may be; our work continues, and we have pushed for laws to be passed. Now that there is a protocol, we keep going. Over the last year and half [since the ban on the emergency contraceptive pill was lifted], we have observed that the protocol has not been implemented.

It is important to clarify that if a person goes to Hospital Escuela or any hospital in northern Honduras, they will be seen by a doctor, but authorities have not established how medical personnel should proceed, so it is not clear whether they know how to comply with the protocol. That doesn’t mean there is no medical care, but personnel could prioritize medical aspects when there is much more to the protocol.

CC: In what respect? What is going on?

JG: As an organization, we understand that there are processes in place, and while it is an achievement that the emergency contraceptive pill is approved within the protocol, we cannot keep medication in a warehouse. It is also necessary to train personnel and to establish a referral system because several medical professionals provide care. Confidentiality is also very important which is why patients should be seen and treated in a single location, if possible. Personnel should know that victims may receive care without filing a complaint.

Requirements concerning mental health, psychosocial support, protection and other aspects within the protocol have not been implemented.

Raising awareness [of the protocol] is crucial, otherwise there is no demand because sometimes victims don’t know that medical attention is necessary after an event of sexual violence, or they understand that care is urgent but don’t know where to receive it – that is what our data show.

CC: What steps are vital for implementing the protocol?

Laura Fonseca (LF): Firstly, we have to establish health facilities, which is not very clear to the population at the moment. Secondly, medical personnel should receive training to administer medication and properly assist victims, including referring them to a health facility, so that they understand that sexual violence is a medical emergency and treatment should preferably be received within 72 hours of the event.

CC: Why is it important for victims to receive care within 72 hours after an event of sexual violence? Are victims and survivors seeking help within this time frame?

LF: That is the period in which most sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV, and pregnancy can be prevented. This is a serious problem because most people don’t arrive at MSF’s clinics within 72 hours. We must ensure the population knows that sexual violence is an emergency that should be treated. We have noticed that many people don’t know there is a protocol and where they can find help.

Most people don’t visit a clinic within 72 hours. Last year, only 12 patients did. According to the victims, this is due to two main reasons: firstly, they feel emotionally overwhelmed; secondly, they don’t know the protocol exists and care is available. Information about the protocol and locations where victims can find assistance has not been clearly conveyed, and health is not promoted at the community level either.

CC: How should health facilities operate and how do referral systems around the country work to assist victims of sexual violence?

LF: It is hard to say how patients will be treated in hospitals, but when a person seeks urgent medical care, we provide emotional support so they don’t feel like a victim, making sure they are comfortable talking to us. From there, we provide mental, medical and social care so that the victims give an account of the event only once. Urgent medical care is provided to victims to prevent sexually transmitted diseases if they arrive within 72 hours of the event and pregnancy if they arrive within 120 hours.

Then, victims receive mental health care, which should be provided early on to prevent more severe disorders. Psychosocial support is also provided to victims since they know the aggressor in many cases; for example, in more than 50 percent of cases in Tegucigalpa. So victims need help to escape the cycle of violence.

CC: How can revictimization be avoided?

JG: Revictimization is an important matter. This is when, for example, a victim gives an account of the event to a doctor, a nurse, a psychologist and then a social worker. To avoid revictimization, victims should be assisted in a single center and by the same personnel so that they don’t relive the events of violence.

- What training should personnel and communities receive to assist victims of sexual violence?

JG: One should not assume personnel know nothing; this is not what we are saying, but we should address fears or preconceptions they might have. I don’t think prejudices is the right word because it has a negative connotation, but people may have certain opinions. They might think they could get in trouble for assisting a victim, or they might fear they will have to testify in court against the perpetrator, who could recognize them. Personnel might withhold medication until the victim is seen by a forensic doctor, which is understandable but wrong since we can provide certain medication without tampering forensic evidence.

Moreover, there are patients who don’t seek help because they are unaware of the protocol. But the goal is to provide a safe space, confidentiality and comprehensive care in each health facility. One has to consider not only the person’s physical health but the mental and social well-being too.

LF: Providing medical assistance within 72 hours of the event is the priority, not filing a complaint. Many people still think it is necessary to file a complaint to receive care.

CC: At what stage is the training of health professionals?

JG: It is our understanding that personnel have been trained, and they can, in turn, train other people. It is worth stressing that the implementation of the protocol is contingent on coordinated participation of the Secretariat of Health, the Attorney General’s Office, Ciudad Mujer (a government program aimed at providing health care and education to women), Unidad de Género (a government institution dedicated to promoting policies and budget allocation geared to a gender perspective and the needs of women), and others.