Only 15 cases of femicide in Honduras have resulted in convictions since the country criminalized femicide in 2013. These cases are brought before a justice system that is poorly trained in gender issues, and recent legislation has reduced the penalties for crimes of violence against women. Women who dare to report domestic violence do not receive timely care and attention – they are not safe – and this can end in femicide.

By Vienna Herrera / Contracorriente

Illustrations by Alberto Rodríguez Collía

From the special series Outposts of Silence (Estación del Silencio)*

Translation: John Turnure

Heidy Garcia still bears the scars of the violence she has endured for years. On October 23, 2018, her ex-partner tried to kill her with a machete. Now 39 years old, her face and body are scarred, and her health has deteriorated. There is still so much pain and fear.

Heidy had to report Andres Martinez for domestic violence five times to get a restraining order. However, no one checked whether the order was enforced, and he returned one day.

“So that he could finish killing me,” says Heidy, who was assaulted the day after her birthday, after she returned home from lunch with a friend. He attacked her in front of her youngest daughter as she was cooking dinner for her children.

“He was going to hit me in the face, but I jerked away out of reflex, and I screamed ‘You’re killing me!’ He said, ‘Yeah, and I’m going to finish you off now,’”

Heidy managed to escape that attack and was admitted to the National University Teaching Hospital (Hospital Escuela Universitario).

Heidy’s case of attempted femicide is now pending before the Supreme Court of Justice. The number of other pending femicide cases is not known; the judiciary did not respond to a freedom of information request placed by Contra Corriente.

In April 2013, the crime of femicide entered into effect in the Criminal Code. However, the Public Prosecutor’s Office only began reporting data on this crime in 2017, four years later. Only 30 cases of femicide have been prosecuted through 2019. This number stands in sharp contrast to the 7,041 reports of murder, infanticide, parricide and homicide filed between 2008 and 2009, in which the victim was female.

Most of these cases have not been prosecuted. Between 2010 and 2019, only 35% of the cases received by the Public Prosecutor’s Office were brought before the courts. Of the 104 cases of femicide that reached the Supreme Court of Justice between 2014 and 2019, only 23 have been adjudicated. Seven of these cases were acquittals, 15 were convictions, and the resolution of one case is not clear since the case file indicates that it involved two charges – a femicide and a misdemeanor. The perpetrator was acquitted of one charge and convicted of the other, but the case documentation does not specify which one.

Avoidable revictimization

Women’s organizations say that more than 90% of the reported femicides go unpunished. “Our perception is that the justice system is less committed to solving these crimes,” says Gilda Rivera, director and founder of the Center for Women’s Rights (Centro de Derechos de Mujeres – CDM). “Crimes against women are widespread because the justice system clearly views them as unimportant.”

The moment Heidy got to the hospital, she began demanding justice. She immediately asked a police officer from a specialized investigative unit called the DPI (Dirección Policial de Investigación) assigned to the Teaching Hospital to write down her attacker’s identification number. She expected the police to act quickly.

But Andres Martinez was not immediately arrested. Two months later, when Heidy found out where he was, she prodded DPI officers to go after him. “I’m doing your job for you. I’m the victim here and I’m doing your job for you. If you won’t help me, I’ll go to the media,” said Heidy. The police consented, but only if she agreed to go along with them. Heidy reluctantly agreed, even though she was afraid of being attacked again.

Alejandra Salgado, a lawyer with the Quality of Life Association (Asociación Calidad de Vida) who protected Heidy after the attack, reports that women like Heidy frequently must conduct their own investigations to provide proof to the police of the violence they faced. This puts their lives in danger. “If she hadn’t moved away, who knows what would have happened to her,” says Salgado.

A system allied with sexism and impunity

CDM’s Gilda Rivera says that one of the biggest difficulties women have in their pursuit of justice is weak institutional commitment. “Even among people working in the justice system, machismo and an oppressive attitude towards women is commonplace. Plus, our institutions are plagued by corruption, where powerful men often receive lenient sentences or decisions that favor them,” says Rivera.

The CDM knows the system well, as it has championed the case of Vanessa Zepeda for years. Zepeda, a nurse, was murdered in 2010 by her ex-partner, neurosurgeon Rafael Sierra. In 2015, Sierra was sentenced to 15 years in prison for murder.

“But Sierra then escaped,” says Rivera. “Hours earlier, he had been at work at the Honduran Social Security Institute [Instituto Hondureño de Seguridad Social], and someone tipped him off about his prison sentence. This is how the justice system works here,” says Rivera. “The Public Prosecutor’s Office has been unable to do anything in this case.”

Five years have gone by and Sierra is still at large.

“In Honduras, a dead woman is just a statistic,” said Vanessa Zepeda’s mother, Bessy Alonzo. “My daughter’s killer murdered her knowing it doesn’t matter if you kill a woman in this country. I read about women being murdered every time I pick up a newspaper. What’s going on here? How many women have to die like this? Why doesn’t the government help us? There is no justice.” Alonzo was quoted in the Oxfam Honduras report “The risk of being a woman in Honduras” (El riesgo de ser mujer en Honduras.)

Since 2008, the Public Prosecutor’s Office has only received 11 training courses on the subject of femicide, while the judiciary has only received one course offered by the Honduran Center for Women’s Studies (Centro de Estudios de la Mujer-Honduras, CEM-H).

For CDM’s Gilda Rivera, the problem goes much deeper than insufficient training and is rooted in unequal power relationships.

“Power is heavily centralized in authority figures who are allowed to do what they want. People often say that those working in the judicial system need more training. That may be true, but we also know some people who have access to training, yet continue to act the same way,” Rivera says.

The Follow-up Mechanism to the Belém do Pará Convention (MESECVI) issued a 2017 report on the reality in Honduras, stating that although the country’s Criminal Code prohibits conciliation between parties in sexual and domestic violence crimes, “… it is not applicable to all crimes of violence against women. According to information received by MESECVI, justice officials continue to allow conciliation, despite the provisions of the Law against Domestic Violence.” MESECVI has asked the Honduran government to prohibit conciliation in cases of violence against women.

Honduras: 104 femicide cases

The Honduran judiciary has recorded a total of 104 cases of femicide (but has not provided a breakdown by municipality and department); 51 of these cases were assigned to sentencing courts and are included in this map.

Source: Honduran judiciary.

Searching for safe haven, against all odds

Even though Heidy managed to have her ex-partner imprisoned for what he did to her, she still doesn’t feel safe. In 2019, she started to get lots of phone calls from different numbers, but the voice on the other end was always the same – her attacker. At first, he apologized and promised that if she withdrew the charges, he would work to support her and their daughter. Heidy replied, “When you did this to me, you lost all your rights.”

Then, Andres Martinez started threatening her.

“I’ll tell you one thing, I didn’t kill you before, but I’m not going to leave it at that. You better watch out because I’m going to kill you, I’m letting this [jail time] go to waste,” she says he told her.

Hearing these threats, Heidy went to the Public Prosecutor’s Office. They tapped her cell phone and gave her security protection for a while.

That’s when she decided to leave the country. She first presented her case to the Secretariat of Human Rights, which provided her with documentation to back up the threats on her life. But she says that her case was assigned to a policeman who showed up just once, to ask for her signature on something.

After all the suffering and threats she endured, Heidy’s predicament got even more difficult. She had bought a home on her own, but never had enough money to pay for the deed registration. This became a source of constant friction with Andrés because he wouldn’t let her work to pay the registration, unless she included him in the deed as a co-owner. Now she can’t live in the house and lives with a relative, who recently started asking her to leave. And she’s struggling to find work because she lost significant mobility in one arm after the assault.

“I was thinking of migrating, but they [the Secretariat of Human Rights] told me that they didn’t get people out of the country and they tried to stop us from emigrating,” says Heidy. “I’m afraid to leave because of my children, but I’m also afraid to stay here.”

Heidy also requested help from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), but her request was denied because Andrés Martínez still shares custody of their daughter.

Alejandra Salgado, Heidy’s attorney, says that they petitioned the Family Court to give sole custody of their daughter to Heidy, but were denied. They were told they had to wait for the sentencing decision of the assault case. The Honduran Civil Code states that child custody can be stripped from a parent “due to the protracted insanity of a parent, if a parent is unable to administer his/her own affairs, or due to a protracted absence by a parent that seriously jeopardizes the child because the parent fails to provide child support.” In the same chapter, the law indicates that such child custody rulings can only be adjudicated by a judge.

Dilcia Castillo, a social worker with the Quality of Life Association, says Heidy is afraid that the entire judicial system will let her down. “The authorities won’t help her. She doesn’t need a temporary solution, she needs a permanent one.”

Domestic violence: ignored and neglected

“When we have a femicide case, it’s because the government has failed to fulfill its prevention role. It has been unable to provide the necessary conditions to protect women, and a woman has lost her life as a result of this ineffectiveness,” said Supreme Court justice Tirza Flores during a forum on femicide.

Men who have been formally charged with femicide are also sometimes charged with a variety of other crimes such as abortion (forcing a woman to have an abortion), acts of lust, breaking and entering, murder, simple homicide, illegally bearing weapons, illicit association, aggravated threats and robbery. Yet domestic violence charges never appear on anyone’s records.

“The Supreme Court receives an annual average of at least 20,000 domestic violence cases. Fifty percent of these cases are vacated because the woman is financially dependent on the man and cannot continue with the case, or because they fall back into the cycle of violence,” says Ana Concepción Romero, coordinator of the Domestic Violence Courts. “The rate of recidivism can only be reduced if a model of comprehensive care exists. Ideally, by the time a case gets to the courts, the woman’s claims have truly been heeded, and she recognizes that if she doesn’t pursue the case, the cycle of violence is going to continue.”

Read more here: An avoidable femicide

Alejandra Salgado, Heidy’s attorney, says: “The government needs to get serious about domestic violence. We’ve heard about ignored domestic violence charges that later become attempted femicide cases. Men are no longer afraid of being arrested for domestic violence because they know the only punishment will be to do some community service like picking up trash or making piñatas.”

Honduran law recognizes various types of domestic violence, including physical, psychological, sexual and property violence. Those convicted of these offenses without causing damages classified as crimes under the Criminal Code are sentenced to 1-3 months of community service. Failure to complete the community service leads to a new offense of contempt of court, which is punishable by a 1-3 year prison sentence.

The current Criminal Code punishes the crime of domestic violence with a 1-3 year prison sentence, and a 2-4 year prison sentence if aggravated by bodily harm, home invasion, drug use, and more. A sentence of less than five years may be commuted to a fine of ten lempiras (US$0.40) per day of the imposed prison sentence.

Heidy claims to have been the victim of all these types of violence, and even suffered a miscarriage caused by one of her ex-partner’s blows. After the femicide attempt, Heidy sought shelter in one of Honduras’ seven women’s shelters. (They are located in Tegucigalpa, Santa Rosa de Copán, La Ceiba, San Pedro Sula, La Esperanza, Choluteca and Puerto Cortés.) They are all private institutions supported by foundations or non-governmental organizations.

President Juan Orlando Hernández’s administration created the Ciudad Mujer program to improve women’s quality of life. The program runs centers that offer support for financial independence, care and protection from violence, sexual and reproductive health, and community education. But none operate as shelters.

Idania Amador, a psychologist with the Quality of Life Association, says that Ciudad Mujer does not provide enough support for women. They’ve made requests to Ciudad Mujer for financial and institutional support for high-risk cases, but so far haven’t received any.

“Our interaction with Ciudad Mujer is that they’ll refer domestic violence cases to us at the shelter, but then don’t deliver on their promises. They bring us women who have nowhere to go from here, so we want to make sure they support us in finding permanent homes for them. The only thing they really help us with is giving clients priority appointments with the doctors,” explains Amador.

Regressive laws

In Honduras, the only specific law pertaining to violence against women is the Law Against Domestic Violence, approved in October 1997. This makes Honduras one of six Latin American countries that, despite having ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), does not have a law that comprehensively addresses gender-based violence.

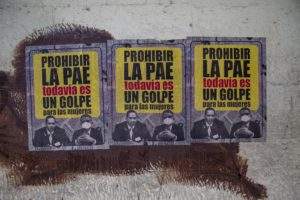

For the first time, the new Criminal Code criminalizes violence against women and devotes an entire chapter to the crime. However, the statutory penalties for these cases are weaker than in the previous code. Despite having been passed in 2018, the new code is still awaiting action by the executive branch, which could decide to repeal or amend the law.

Women’s organizations point out that the new Criminal Code weakens the sentences for crimes of violence against women, and even eliminates some. The sentence for femicide has been reduced to 20-30 years in prison; previously it was 30-40 years. Similarly, the sentence for rape has been reduced to 9-13 years; previously, it was 10-15 years.

MESECVI points out that there is also no explicit regulation in the Criminal Code on rape and sexual abuse within marriage and de facto unions. According to information MESECVI obtained from Honduras’ National Demographic and Health Survey (Encuesta Nacional de Demografía y Salud – ENDESA), 22% of the women who reported having a husband or partner indicated that they had experienced one of three forms of violence (physical, psychological, or sexual) by their partner during the previous 12 months. Furthermore, 21% were victims of psychological abuse, 10% of physical violence, 3% of sexual violence, and 11% were physically and sexually abused.

For Gilda Rivera, the most serious problem is not the weaker penalties. “I don’t think acts of violence against women will decrease becasue of longer sentences – that’s a monitoring and punishing strategy. I believe that violence against women will decline through preventive measures and greater government responsibility, rather than through punishment.”

So far, government measures to address violence against women include the creation in 2016 of a special investigative unit (Unidad de Investigación de Muertes Violentas de Mujeres y Femicidios) within the Public Prosecutor’s technical agency for criminal investigation (Agencia Técnica de Investigación Criminal – ATIC). At the same time, an inter-institutional commission for monitoring violent deaths and femicides (Comisión Interinstitucional de Seguimiento a Muertes Violentas y Femicidios) was established and began work in 2018. It is composed of government institutions and representatives from women’s organizations.

Honduras: 2 femicide units and 14 courts

In Honduras, the Public Prosecutor’s Office has two femicide units: one in the special prosecutor’s office for the protection of women, and the other in the prosecutor’s office for crimes against life. Femicide cases are heard by 14 non-specialized sentencing courts in the judiciary.

Sources: Honduran Public Prosecutor’s Office and Judiciary.

However, in 2019, some of the feminist organizations represented in the commission issued a follow-up report claiming that, “there have been just a few, mostly verbal reports of these crimes, and most didn’t even result in an arrest warrant.” Additionally, only 21% of the funds earmarked for preventing and investigating violence against women have been disbursed, and it isn’t clear what the money has been spent on.

ATIC spokesperson Jorge Galindo told Contracorriente that the special investigative unit only operates in San Pedro Sula and Tegucigalpa, and travels to other regions when high profile crimes occur.

Regarding the cases investigated by the unit so far, Galindo says that “All of them involve violent deaths of women. The prosecutor then determines if the crime of femicide has occurred”. He adds that there are only 50 ATIC agents to investigate crimes nationwide.

A social audit of ATIC’s research unit conducted by various women’s organizations and Oxfam International, reports that as of 2018, only 28 cases had been opened, of which only four were for femicide.

The projection for the first three years foresaw that, “the special investigative unit would investigate 220 cases of women who had been murdered or were victims of femicide. However, this target has not been met,” the report notes. “There is no data on the result of ATIC’s commitment in this regard.”

Two years after Heidy survived a femicide attack, she is still waiting for her attacker to be sentenced, scheduled for October 21, 2020. After taking action on her own to seek justice, she says she doesn’t feel safe.

“There’s no way I’ll ever live in peace. I’ll always be afraid,” she says. “I can’t give him time to think about what he wants to do to me, to find another way to attack me.”

Heidy doesn’t trust the protection her country can provide. It has failed her so many times.

* “Outpost of Silence” (Estación del silencio) is a transnational project coordinated by Agencia Ocote that investigates and analyzes violence against women in Mesoamerica. This article is part of a first report on femicide by the following organizations: Agencia Ocote (Guatemala), elFaro (El Salvador)y ContraCorriente (Honduras).

Supported by the Foundation for a Just Society, Oak Foundation and Fondo Centroamericano de Mujeres.