Comayagüela is the commercial epicenter of the capital of Honduras and also the most unequal. There, violence and multiple expressions of survival converge. On the main street of the Las Crucitas neighborhood is Rinconcito Jamaica, a safe space for internally displaced Garifuna women who see Olivia Sierra, the owner, as a matriarch to whom they can turn when their lives are in danger.

Text: Vienne Herrera

Photography: Jorge Carbrera

Translated by: Amy Patricia Morales

Olivia Sierra closes her front door and leans against it, standing in a hallway encircled by staircases. As she enters to engage in conversation, she does so quietly to prevent the conversation from seeping beyond the walls. In 2014, a criminal organization killed her eight-year-old granddaughter. This, the result of her daughter Marcela refusing to work for them. Marcela applied for asylum in the United States and left with her son, a six-month-old baby.

For her safety, the name of the gang that controls her neighborhood will be omitted. Olivia Sierra looks nervously at her surroundings, she wants no one to hear us.

She whispers into the recorder: “They killed her [my granddaughter] because my daughter did not want to sell drugs.”

Sierra wears a turban that conceals her hair and a traditional Garifuna blue dress adorned with vibrant green, yellow, red flowers, as well as black-colored dots and squares. Her dress stands out vividly against the backdrop of the gray wall.

The woman who fears being heard is 50 years old. She was born in Triunfo de la Cruz in Tela, a Garifuna town, that survives off fishing on the Northeast coast. Her mother was poor and her father abandoned them during pregnancy.

The Garifuna community descended from enslaved Africans, who inhabited the Caribbean island of Saint Vincent. In 1797, they settled along the coast of Honduras. In the last decade, these communities have struggled against land displacement due to extractivist projects, drug trafficking, forced disappearance, and judicial harassment.

Sierra returns to Triunfo de la Cruz at least twice a year to visit her family.

Sierra says she doesn’t know much about the displacement. The ancestral lands of the Garifuna people are of interest to hotel resorts, which has led to violence against them. Kidnappings, murders, threats, criminalization, displacement, and disappearances are among the problems that have left a mark on a place that has been emptying for decades due to economic insecurity.

Dispossession and poverty causes high levels of displacement from Triunfo to urban areas. Among them, to Comayagüela. Comayagüela and Tegucigalpa jointly hold the designation of the capital of Honduras within the Central District. Both cities evolved with the internal migrations, but their urban design has stifled individual aspirations and strained social connections.

Olivia Sierra’s mother migrated with her daughter to the Capital city when she was just three months old. Since then, she’s lived in Comayagüela, 300 kilometers of distance, with her daughter Denia and her six grandkids. She’s been displaced at least six times in the city.

Comayagüela relies on the informal economy for its sustenance, making it one of the most unequal places. This peripheral city is inundated with a myriad of survival tactics, where one can come across everything from food to secondhand clothing.

Olivia Sierra has a house in the Fuerza Unidas neighborhood in Comayagüela. However, she says that she had to abandon her house due to a criminal organization attempting to seize it from her. For the past four years, she has been residing in the Las Crucitas neighborhood within the same city.

At Las Crucitas, houses sit on top of one another. They emulate the same structure mountains take, upon which their houses are constructed. The majority are painted green, purple, or blue. It’s not a predominantly Garifuna neighborhood but more Afro-Hondurans live here than any other neighborhood in the Central District.

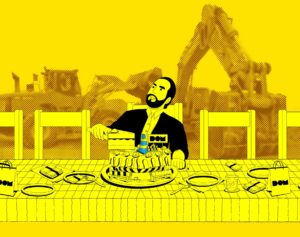

Rinconcito Jamaica is on the main street of Las Crucitas. Founded in 2018 by two Garifuna men, it’s now home to Olivia after she rented the room sitting above the business. Since then, they abandoned the house and left Olivia with it. “From one day to another, they left for Mexico” she recounts to share how she became the owner of the business. To enter Rinconcito Jamaica, you have to walk in through a makeshift door. You can see cases of empty drink bottles and chairs on top of tables. They sell Garifuna products and sell food like coconut bread, coconut oil, and gifiti (aguardiente, or firewater macerated in chamomile and eucalyptus). At night, people dance punta (a traditional Garifuna dance), dancehall, and reggaeton.

She did not let us enter Riconcito. Beyond being a business, it is also a refuge for Garifuna women.

In the last decade, she helped her daughter escape and at least 15 other Garifuna women and internally displaced women, seeking refuge. Rinconcito has served as a refuge where women can live temporarily and connect.

The majority of women search for Olivia Sierra when they have also fled gender-based violence or threats from gangs or armed organizations. She offers her house as a place of refuge, meanwhile, they tend to Rinconcito Jamaica. Sierra supports them economically so they can flee.

Threats are not sent to us; they simply arrive

The women refugees at Rinconcito live through gender-based violence in silence. When they ask Olivia Sierra for help, she offers it without asking too much. They trust her because she’s known for lending a hand to other women. While at the same time, remaining cautious.

“Here we don’t receive threats, they simply arrive,” says Sierra, nodding her head and crossing her arms.

The last woman she helped at Rinconcito was in 2020. She lived for a while at Olivia’s house and later left for the United States in December with her six children. “That day, Rinconcito was open, we had no choice but to take the money we had saved up for rent, and we gave it to her so our comrade could leave,” says Olivia.

Olivia Sierra’s eyes are filled with tears.

The warrior Barauda

For 10 years, Olivia was a part of Barauda, an association comprising of 26 Garifuna women, internally displaced from the violent neighborhoods of Comayagüela. Barauda is the name of a Garifuna warrior who fought against the Spaniards on the Saint Vincent islands in 1795 and now a symbol representing the historical fight of Garifuna women.

The Barauda association used to sell bread up to 2017, when a gang, “those people”, as Olivia refers to them, stole and ransacked the place, a block right before Rinconcito Jamaica. Following this incident, the association searched for alternative locations to sell at, but were robbed again, and as Olivia Sierra recalls, some members “raped, including their daughters”.

A few meters from Las Crucitas is the Belén Police Station, a place that has been denounced given the poor conditions its facilities are kept in and its staff purge, having reduced almost half of their employees.

It’s June 3rd, 2021 and the sidewalks of the neighborhood are busy. Women sell fried steak with beans, a common dish in Comayagüela and Tegucigalpa. Some men repair vehicles in street repair shops.

Olivia feels a strong sense of community among the Garifuna people in a city predominantly mestizo. “A little corner where we can look after our dead, when they die of illness or are killed, where we can dance punta, celebrate important events such as the 200th anniversary of our arrival to Honduras (..) there is a little corner for everyone,” says Olivia.

The matriarch speaks inside a hallway in her building. She does not move away from the door. From time to time, she makes her keys rattle in her hands. Olivia speaks candidly about her life but she sets boundaries over what we can know about her. She does not invite us to enter el Rinconcito or her home.

Reviving the joy of the Garifuna community is not an easy task when it’s surrounded by violence. The Honduran government does not categorize violence by neighborhoods, but Las Crucitas, her neighbors say, is very dangerous.

Las Crucitas is just a few meters from neighborhoods like Los Profesores, Bellavista and La Obrera, areas that, according to the National Police, have a high presence of organized gangs. In the absence of data, violence is measured by incidents like assaults and robberies, or more overt incidents such as unpunished murders. Life in these neighborhoods is narrated through the lens of different manifestations of violence.

In Honduras, the term “barrios” is used to describe impoverished areas controlled by gangs and armed groups. It is an ambiguous term but dominated by one clear meaning: latent danger of death.

The Honduran Penal Code has recognized domestic violence as a crime since 1997. During the first decade, the national figure barely reached 12,000 complaints, according to data from the Public Prosecutor’s Office. The number of complaints doubled in 2009, after the coup. Since then, every year the figure only increases.

A culture of silence affects the figures of gendered violence in the neighborhoods. In 2020, the National Emergency System registered 282 daily complaints of gender-based violence. Most of them did not go to trial. The annual report of the Judiciary noted that only 715 hearings were held for this crime.

Francisco Morazán, the region where Comayagüela is located, is the region that reports the most domestic violence complaints to the National Emergency System. In 2020, Honduras ended the year with more than 90,000 reported cases of domestic violence. Of these, 10,020 came from the Central District. By the end of July 2021, there were 5,758 cases from the Central District.

The Garifuna culture follows a matriarchal tradition, which is why women turn to Olivia for help. Rinconcito and Olivia are their sanctuaries within the city. Olivia refuses to speak about the reasons women flee because in neighborhoods controlled by gangs and armed groups, there is no channel to make a formal complaint against the gender-based violence.

The police should not enter the area without warning first. “Here, daughter, it’s, see, hear and shut up, that’s the only way to survive. You cannot participate, nor say anything at all. If you say something, or talk or call the police, for example, before they arrive, you are already dead,” says Olivia.

When experiencing domestic violence, asking criminal groups for help is not an option either. “If you call and tell these people – gang members – that you are suffering domestic violence from your partner, it’s practically as if you are selling your soul to the devil because by doing so, in their view, you become one of them.

Olivia does not allow us to speak to the women she helped. She protects them, just as she protected her daughter, her grandson, and herself. Both of her two daughters also do not want to talk about what it is like to be a woman in Las Crucitas or what motivates them to flee from one day to the next.

Silence prevails as a form of self-protection. Women flee with fear.

The location of the impacts

In central Honduras, Comayagüela is the place where the blows hit the hardest. In 1998, the devastating Hurricane Mitch hit the city so hard that more than twenty years later there are still visible after-effects in its neighborhoods. The first case of COVID-19 in Honduras was recorded in Comayagüela.

In the early months of 2020, the Honduran government imposed a curfew that resulted in the complete shutdown of Comayagüela, a place where the majority of people primarily depend on the informal economy for their survival. It was in this area that the military took control and, with the help of police, repressed people who ventured into the streets in search of food.

El Rinconcito Jamaica remained closed for 10 months. During this time, Olivia Sierra began selling coconut bread at the store’s entrance. The bread is a Garifuna recipe with easy-to-find ingredients. She sold each loaf for 10 lempiras (42 cents). This is how she survived the beginning of the pandemic.

“We learned to save, not to give food away; we learned to eat with the pandemic,” Olivia says and laughs. Her laughter is ironic. They could only eat what was easily accessible. “It was dramatic, but educational,” she says as her smile fades.

Between December 2020 until the end of 2021 Olivia did not help any women flee Honduras. Now, she’s focused on supporting the women who have not left and seek to survive in the barrios. At Rinconcito, she sells the coconut bread that the other women make. Sierra does not allow us to talk to these women either.

What did not change with the pandemic was the dynamics of the neighborhoods in this city. Borders still remain, and so does the fear of crossing them. The women who speak do so with fear, they do not want to give their names but they say that they do not feel free, that the rule is to go from home to work and vice versa, never to stray elsewhere.

But that fear marks a deep class division. There are stigmas about certain neighborhoods – such as Las Crucitas – that prevents them from accessing stable employment. Most of the women who have a job work in domestic labor or informally, such as selling in markets or on the streets.

Why do many women from the interior of the country, like the Garifuna, migrate to a neighborhood riddle with conflict in a violent city?

Olivia preferred to put down roots in Comayagüela and maintain her Garífuna identity, so far from the coast where she was born because it has offered her more opportunities to sustain her livelihood.

Olivia adopted Denia twenty years ago, whom she knew because her family – still living in Tela – was Denia’s neighbor. The girl had lost her mother at the age of 12. At 14 she moved with her from Tela to the capital.

With Denia’s 34-year-old children, Olivia Sierra watches through social media and video calls the life that, far away from her, Marcela and her grandson, now 8 years old, now have.

When Marcela arrived to the United States, she told her mother that she is a lesbian and that she had many dreams to fulfill being there. She wanted to study to become an otolaryngologist. Now Marcela is married to a woman and studying the career she wanted.

“I am happy for my girl, I accept her as she is because she is my daughter. If she is happy I am happy too. She has her life made with the girl she married, they love each other, they respect each other, and they are raising my grandson together,” says Sierra with a smile.

Many Garifunas gravitate towards the city, driven by the presence of family or acquaintances already living there. But the neighborhoods where they come to live in are generally dominated by gang violence, armed groups, assailants and racism, which is why many women eventually end up fleeing the country. While there is a reason that exists, it does not resonate within the explanations provided by the women. When they recount their experiences of mistreatment, abuse, or physical harm, they refrain from labeling it as gendered violence.

Olivia thought about leaving many times. She never did. Now she says she wants to go to see her daughter in the United States, but the migration route seems very dangerous and difficult to travel at her age.

“In this beautiful country like Honduras, life is every person fending for themselves,” says Olivia, with sadness and resignation.

There is something Olivia Sierra repeats to herself many times: the best thing that could have happened to the fifteen women she helped escape was to get out of the neighborhoods that make it impossible for them to have a dignified life.

Olivia Sierra says she has slept little, that she is tired.

Olivia rattles the keys again.