Text: Vienna Herrera

Photography: Martín Cálix

“I didn’t even know that the ECP – Emergency Contraceptive PIll – existed. Seven years ago, they raped me when I told my mom and dad that I didn’t like men. My dad abused me. He told me that he was going to make me a real woman,” Ana whispers her story and looks at the floor. Nervously, she touches her hands.

“He beat me so I wouldn’t give birth, and I was scared because my mom told me that if I got pregnant, she would kick me out of the house.” Ana says that even though she began to accept her fate, at three months, she had a miscarriage because she did not know how to take care of herself. She sighs as she remembers that they were twins, that when she went to her mother for help, she kicked her out of the house. She did not believe her. “She ended up saying that I had slept with him.”

While there is no exact data on the number of rapes in the country, according to the statistical register of Forensic Medicine, complaints filed in the last 10 years increased to a little more than double. During 2008, there were 1241 cases of women raped, whereas in 2017, 2761 cases were counted.

All of these alarming figures of sexual violence against women in Honduras occur in a context where there is no protocol for the care of victims of sexual violence and the use, sale, and distribution of Emergency Contraceptive Pills (ECP) have been banned since 2009, almost 10 years ago.

A woman from the municipal cleaning unit works sweeping the Cervantes Avenue in downtown Tegucigalpa. The majority of the city of Tegucigalpa’s cleaning workers are poor women who come down from the surrounding neighborhoods of the capital to sweep and pick up garbage from their streets. Photo: Martín Cálix.

A woman from the municipal cleaning unit works sweeping the Cervantes Avenue in downtown Tegucigalpa. The majority of the city of Tegucigalpa’s cleaning workers are poor women who come down from the surrounding neighborhoods of the capital to sweep and pick up garbage from their streets. Photo: Martín Cálix.

Women are the most vulnerable to suffer sexual violence. Just in 2018, 88% of cases evaluated by Forensic Medicine were women, 58% of whom were minors.

Nevertheless, the complaints filed are just a small percentage of the real violence. According to a report from the Center for Women’s Studies (CDM), only 10% of survivors of a sexual assault report it. Those who do not report it is because “the same society, through its institutions, reinforces and reproduces the idea that the victim is responsible for what happens to them, generating stigma and blame on them,” reads the report. Ana did not report on any of the incidents.

A group of women in the waiting room of the Clinic for Adolescent Mothers, a branch of the University School Hospital in the city of Tegucigalpa. Photo: Martín Cálix.

A group of women in the waiting room of the Clinic for Adolescent Mothers, a branch of the University School Hospital in the city of Tegucigalpa. Photo: Martín Cálix.

“I was young, I didn’t know anything. I didn’t even have my mom’s support. The second time – that he raped her – was because I showered immediately. I felt gross, and since he did it when I was asleep, I didn’t have any proof.” Now, Ana says that she has a group of friends who have gone through the same situation, and who encourage them to file a complaint. As if it were a secret, she confesses that she does it knowing that there will probably be no justice. “I know that here in Honduras, it is worth it to them.”

In 2017, the Supreme Court issued 104 acquittals and only 135 convictions for sexual assault. Several cases among them are not from that year but have been delayed for years due to the backlog that currently has 85,000 cases awaiting resolutions, according to official figures.

The opposition to ECPs in Honduras

The first attempt to ban the ECP was in April 2009, shortly before the coup d’état, with the approval of a ruling promoted by Liberal politician Martha Lorena Casa. She stressed that the pills performed a “pharmaceutical abortion” and “12 to 16-year-old girls take them after a night of partying.” This decision was supported by an opinion issued by the president of the Medical Association at the time, Mario Noé Villafranca.

The President at the time, Manuel Zelaya Rosales, vetoed that ruling arguing that approving it violated international agreements. However, during the de facto Micheletti Baín government, Mario Noé Villafranca was appointed Minister of Health, and in his position, he signed a ministerial agreement issued on October 21, 2009, which prohibited the sale, use, consumption, and distribution of emergency contraceptives.

Villafranca is currently a congressman for the Democratic Unification Party (UD). In a televisión program at the beginning of the year, he said openly that he would support the National Party taking the presidency of the National Congress. Hence, how he got the vice president position of the board of directors and currently also chairs the health commission.

El diputado electo Mario Noé Villafranca confirmó en #FrenteAfrente que apoyará al partido oficialista a obtener la presidencia del Congreso a cambio de la construcción de un hospital oncológico público. pic.twitter.com/L0ZdT9Dz69

— Frente a Frente (@FrenteaFrenteHN) 10 de enero de 2018

Elected politician Mario Noé Villafranca confirmed on #FrenteAfrente (name of the tv program) that he will support the ruling party to obtain the Congressional presidency in exchange for the construction of a public oncology hospital.

In addition to being a politician, Villafranca is also a medical oncologist. He receives his patients in a clinic that has a picture of Jesus Christ in the background and a bible on his desk. In the midst of these symbols, he recalls the regulation he signed in 2009. “Yes, I banned it. I did it because they were abusing it. There were girls that used it 3, 5, 7 times a week. Can you imagine? It’s a bomb. Besides being considered a micro-abortive, it is also related to liver cancer, endometrial cancer, breast cancer, it is a very delicate issue.

Mario Noé Villafranca, former Health Minister during the Roberto Micheletti period after the 2009 coup d’état, and currently is a representative in the National Congress for the Democratic Unification Party (UD). Villafranca presides over the Health Commission of the National Congress. Photo: Martín Cálix.

Mario Noé Villafranca, former Health Minister during the Roberto Micheletti period after the 2009 coup d’état, and currently is a representative in the National Congress for the Democratic Unification Party (UD). Villafranca presides over the Health Commission of the National Congress. Photo: Martín Cálix.

Villafranca says he cannot comment on whether he still thinks it is abortive because, during the first quarter of 2019, the issue will be debated in the National Congress, encouraged by recommendations made by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO).

“They have this idea that it can be regulated, that it can be sold but with extreme caution. The more accurate way would be if it was like psychiatric medications, where they must be rigorously evaluated in order to give it to the patient. A special prescription. As a commission, we’re open to listening,” he concludes.

Since its prohibition, the only institutional debate that has taken place on the issue was in 2013, when Nationalist congressman Ramón Bulnes introduced a bill to legalize it, but it was again shelved. Since then, the issue has been on the agenda of women’s organizations that consider that the ban violates the right to the physical and psychological health of women and girls in the country.

Ericka García, member of the Strategic Group for the Decriminalization of ECPs (GE-PAE in Spanish), which brings together several feminist and women’s organizations on sexual and reproductive rights activism, claims that there is a lot of misinformation and manipulation around it, especially from groups that call themselves pro-life who argue that ECPs are abortive. “They have no scientific or medical basis, just purely religious fundamentalism. With the agreements that the current government has signed with religious leaders, we know that the rights of women aren’t guaranteed and are more like a point of negotiation,” she explains.

Ericka García of the Center for Women’s Rights in her office in Tegucigalpa, Photo: Martín Cálix.

Ericka García of the Center for Women’s Rights in her office in Tegucigalpa, Photo: Martín Cálix.

The World Health Organization (WHO) says that the ECP “can not cause an abortion” because they are based on levonorgestrel, a compound that prevents or delays ovulation so that the sperm cannot fertilize the egg. The WHO also requires that they be implemented in all countries within their family planning programs and services for populations most at risk in an unprotected sexual relationship, such as victims of sexual assault.

Fertilization can occur up to five days after the sexual act, depending on the moment of ovulation the woman is in, therefore, the ECP should be taken in the first 72 hours after an unprotected sexual relationship or a sexual assault. If the egg has already been fertilized, the ECP will have no effect.

The Office of Research in Reproductive Health at the University of Princeton in the United States revealed in a study that ECPs do not cause abortions because they do not inhibit implantation. They evaluated women who took an ECP after ovulation and showed that they had the same chances of becoming pregnant as if they were not taking them: ‘If levonorgestrel were effective in preventing implantation, it would certainly be more effective when taken after ovulation.’

Despite this, the association Pro-life Honduras, founded by Martha Lorena Casco, considers the ECP as abortive, much like any other contraceptive method, such as condoms, pills, and injections, whatever prevents fertilization. They emphasize that they do not approve of any method that is not “natural”, according to their secretary’s explanation by phone in one of the conversations they had after more than three weeks of trying to contact at least one member of the organization for an interview that never happened.

Still, they have made statements on other occasions on this topic. Mercedes Acevedo, member of Pro-life Honduras, said on Radio America during the 2017 National Congress debate on abortion that the ECP is abortive and they are against them. “Our position is that an abortion is an abortion, whether in moments of rape, incest. They are a social problem of the breakdown of the family. Let’s not blame the helpless children in the wombs of their mothers.”

Seven years have passed since Ana was raped by her father. She says that if he had known about the ECP and could have used them when she was 13, she would have done it and have avoided a lot of suffering. Unfortunately, that was not the only instance of sexual assault that she had to suffer.

A soccer match between women to promote women’s rights and the decriminalization of the Emergency Contraceptive Pill, ECP. Photo: Martín Cálix.

A soccer match between women to promote women’s rights and the decriminalization of the Emergency Contraceptive Pill, ECP. Photo: Martín Cálix.

The Yuzpe method and its secondary effects

Less than three months later, Ana was raped again when she stayed at her friend’s house after a party. He abused her while she was sleeping. Ana did not know any way to prevent pregnancy, but a trusted friend showed her how to use regular oral contraceptives.

The Yuzpe method is an emergency contraceptive technique that consists of taking regular oral contraceptive pills that contain levonorgestrel and taking them in higher doses. Depending on the brand, they take between two to four pills, taking the same amount as the first dose of ECP within 72 hours after the sexual assault and another dose 12 hours after the first.

According to Ericka from GE-PAE, this method is 20% less effective than the ECP, which is 95% effective. Additionally, it has greater side effects for women due to the high doses needed to reach the quantity of levonorgestrel that the ECP contains, “which are made so that in a single dose or sometimes in two, they suffer fewer consequences. In the end it’s only medicine,” she notes.

Not only did Ana have to suffer psychological, physical, and social trauma from a second sexual assault, but also, bodily side effects for not being able to access an ECP and having to use the Yuzpe method. “I thought I was going to die because they gave me side effects that I didn’t like: vomiting, shivers, headache, things like that that lasted about 6 hours.” Ana looks at the desk in front of her with pain, as if the effects were happening to her body again.

The Yuzpe method is one of the alternatives in the face of the ECP ban, the other is obtaining it covertly. The ECP is also known as “Plan B” since that’s the brand that comes into the country secretly. Plan B pills are sold in Facebook groups, markets, and pharmacies. Their price varies between 80 up to 300 lempiras ($3-$12 USD).

This illicit sale occurs in a context in which medicines do not go through a sanitary registry, which increases health risks for the women who use them.

In August, a forum was held called “Sexual Violence and Pregnancy: The Pending Challenges of the Honduran State”, a gathering with specialists and authorities, sponsored by the Strategic Group for the Decriminalization of the Emergency Contraceptive Pill, GE-PAE. Photo: Martin Calix.

In August, a forum was held called “Sexual Violence and Pregnancy: The Pending Challenges of the Honduran State”, a gathering with specialists and authorities, sponsored by the Strategic Group for the Decriminalization of the Emergency Contraceptive Pill, GE-PAE. Photo: Martin Calix.

Care for victims in Tegucigalpa

To be a victim of sexual violence is difficult, but in Honduras, the situation is even more complicated. The authorities have cared little about the subject. In the health centers, in the University School Hospital (HEU in Spanish), and the Health Secretariat itself refer all responsibility to Doctors Without Borders (MSF in Spanish), an international, humanitarian mission that has existed in Honduras since 1974 and has dedicated 10 years to treating victims of sexual violence and aggression.

MSF has Priority Attention Centers in two departments in the country: Cortés (in Choloma) and Francisco Morazán. In the latter, they can be found in three different places: the Alonso Suazo Health Center, the Comprehensive Center next to the Prosecutor’s Office in the Dolores, and at the University School Hospital, where they dedicate themselves to providing comprehensive care in medicine, mental health, and social work assessment.

According to MSF records, last year they treated more than 500 cases of sexual violence against women, 66% of these were violations with penetration. The majority of the victims were minors (54%). The data they have for 2018 indicates that by September they have already exceeded 500 cases.

Ericka says that almost always it’s assumed that the assault is the woman’s fault for walking drunk, going to clubs, dressing in a certain way, despite the fact that the majority of reported cases are events that occur within the home. The figures from MSF support it. The majority of registered assaults were by family members, partners, or acquaintances in everyday places like the home, work, or an institution.

Ana also knows that. Her rapes happened at home by three people she knew and trusted, but she also said that they tried to rape her three more times. One incident was at a friend’s house, a friend that was taking her in when she was living on the street. “He was my friend’s dad. He tried to take advantage of me because I was living in their house and I didn’t allow it.”

For Rafael Contreras, coordinator of Doctors Without Borders in Honduras, the doctors that treat cases of sexual assault are very limited in providing comprehensive care because they cannot prevent an unwanted pregnancy. They can only give antiretroviral medicine and prophylactics to prevent sexually transmitted diseases, injections against Tetanus and Hepatitis B, illnesses that can be transmitted by the violent event.

Rafael Contreras, Director of Doctors Without Borders in Honduras, in their offices in Tegucigalpa. Photo: Martín Cálix.

Rafael Contreras, Director of Doctors Without Borders in Honduras, in their offices in Tegucigalpa. Photo: Martín Cálix.

During follow-up of these cases, Doctors Without Borders cared for 36 pregnant women, 81% of which indicated that their pregnancy was the product of rape. Mireya Hernández, a psychologist from the Emergency Adult Crisis Intervention Unit at HEU, says that the patients that are victims of rape “always come without wanting to talk. They come in with depression, suicidal thoughts, anxiety, and mental disorders because of the abuse and fear that they might be pregnant.”

Contreras notes that women are often greatly affected by an unwanted pregnancy. “Some show it, not only at the moment of childbirth, but later on they make it clear that this is not the beloved child that one might think of, but is someone or something that permanently reminds them of the violence they suffered.” He adds that other risks they run are carrying out an unsafe abortion, poor nutrition during pregnancy, risks of sexually transmitted diseases, depression, and suicide attempts.

Ana Raquel Gomez, a doctor from the Clinic for Teen Mothers at HEU, says that each month they receive at least two patients whose pregnancies are the product of sexual abuse, usually by someone they are related to or someone they know that lives nearby. “We don’t know who the man is and if he has sexually transmitted diseases. Some have come with warts and we have to treat them so that the baby isn’t born with any problems.”

Nahomy Alas, a psychology student that completed her professional practice at the HEU, recalled that one of the cases that most affected her was when she treated a woman who was abused by her uncle and was two months pregnant. She arrived at the HEU after an attempted suicide: she had ingested detergent. “She told me that she didn’t want to kill herself, she just wanted to induce a miscarriage, and two days later, she died. It’s shocking to see a patient that you’re treating, that reaches a catharsis and that the only thing you can do is watch her knowing that in the end, she’s going to die.”

The Women’s Human Rights Observatory of the Center for Women’s Studies (CDM) notes that in 2017, more than 800 girls younger than 14 years old became pregnant from sexual assault.

At the moment, the care that victims of sexual violence receive is different across the country. Maribel Navarro, a member of the Standardization of the Health Secretariat, says that they are being treated depending on the internal regulations that the health centers and hospitals have.

However, one of the problems that Doctors Without Borders have identified in the HEU is that, sometimes, without a formal complaint, the doctors won’t attend to the victims. “Reporting can not become a barrier because it is the person’s right, not their duty,” says Contreras.

Meeting of the Political Agenda of Women and Feminists in a hotel in Tegucigalpa, August 14, 2018. Photo: Martín Cálix.

Meeting of the Political Agenda of Women and Feminists in a hotel in Tegucigalpa, August 14, 2018. Photo: Martín Cálix.

An incomplete protocol

Honduras is the only country in Latin America that does not have a protocol to care for victims of sexual violence. For more than two years, it began to create one with the support of diverse organizations like Go Joven, MSF, OPS, the United Nations, women’s organizations, and the Health Secretariat, among others.

The draft of the protocol was introduced in October 2017. Since then, the technical agency that worked on it did not hear about it until January when it was announced that it will begin to be used. But that the part about pregnancy prevention, which includes the use of the ECP, has not been approved.

Rafael Contreras from MSF says that “what we know unofficially is that they have a problem with ECP because it’s prohibited. But when they talk about integrity, they need to talk about pregnancy prevention. At no point in the protocol does it mention abortion, only prevention with a medication that is preventative. Apparently, there may be a political, religious problem for which they have not validated it.”

Meanwhile, Maribel Navarro, says that “because there is a ministerial regulation, they have removed the part about pregnancy prevention from the document and now steps are being taken to repeal it. The minister is investigating a little more to make this decision.”

Women attending the forum “Sexual Violence and Pregnancy: The Pending Challenges of the Honduran State,” completed in August 2018 as part of the permanent campaign for GEPAE for the decriminalization of the Emergency Contraceptive Pill. Photo: Martín Cálix.

Women attending the forum “Sexual Violence and Pregnancy: The Pending Challenges of the Honduran State,” completed in August 2018 as part of the permanent campaign for GEPAE for the decriminalization of the Emergency Contraceptive Pill. Photo: Martín Cálix.

When the walls woke up screaming

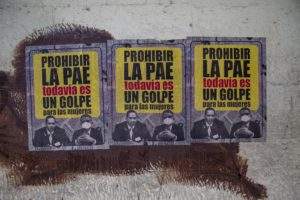

When they realized that they wanted to approve the protocol without the pregnancy prevention section, the Strategic Group for the Decriminalization of the ECP (GE-PAE) sent a letter asking for an explanation from the Secretary of Health, Octavio Sánchez Midence. When they did not receive an answer, they met with youth and ran brainstorming sessions to create an idea that links ECP with sexual violence.

At that time, a case arose that generated a lot of indignation in various sectors of society. Silvia Vanessa Izaguirre, who was 28 years old and a student in her last year of medical school, was returning from her vacation when her transportation was interrupted by assailants who tried to rape her. Silvia resisted them and was murdered. The case generated mobilizations, sit-ins, protests, and statements against gender-based violence in its highest expression: femicide.

Read more here: Los femicidios oscurecen el panorama hondureño

In this context, the poster campaign “I do not want to be raped” is born and the streets begin to be covered. The eyes of a woman and the phrase in big letters, with a list underneath of potential perpetrators: partner, professor, father, uncle, among others. They were stuck onto the walls of several cities throughout the country. The day that the campaign begins, a case of rape is reported inside a bathroom in the facilities of the National Autonomous University in the Sula Valley (UNAH-VS in Spanish).

Read an opinion column on this topic: Peligro Inminente

As a result of this, the campaign became massive. Photographs of the signs were covered by media and the movement began to take hold. However, the GE-PAE also documented several violent incidents. In the streets, they removed the posters, crossing out the “no” so that it said “I want to be raped”, and wrote things on them like “close your legs”, “why do you dress like that”, and made attacks through social networks.

“As if it offended them. Then that shows the culture of machismo violence that we have in this country. Like when a man walks down the street and sees a poster like that and it bothers him, it annoys him, it’s because there’s something there,” says Ericka.

Another violent event that occurred during the campaign was the use of the shirt that had the same image of the poster. When they wore the shirt, women reported more street harassment. Cars, motorcycles, and men would follow them. Men would even start touching them. Since the stalkers had to see the constant reminder and since the women’s bodies generated a much more violent reaction than usual, as a security measure, the girls had to restrict the use of the shirt to only wearing it when walking in groups.

Ericka adds that in the country where they live in “a culture of extreme violence, where harassment is also incredibly violent, women are afraid. And our fear is that they will kill us because of the high numbers of femicides. But also that they will rape us, that they’ll assault us. We live in a constant state of stress.”

This harsh reality of sexual assault against women increases over the years. Preventing an unwanted pregnancy resulting from rape is now in the hands of the Minister of Health. People are aware that the Ministry of Health is thinking about it, but no one knows what their response will be, despite all of the scientific evidence they are being given. The wait could last for years. Years in which the reality of women like Ana will continue repeating itself, without adequate attention.

Ana has thought about committing suicide. She says she doesn’t know what to do anymore. In spite of everything, she is dedicated to helping other women overcome their experiences with violence while trying to erase her own. Four years ago, one of the men who tried to rape her cut off her leg, and they had to give her 12 stitches, which left a scar. Ana got a tattoo to hide her scars. She sighs and reflects on her life.

“Yeah, it’s been hard.”

Note: The names of survivors have been changed for their safety.

Translation by: Witness for peace, Honduras team.