Xiomara Castro became the first female president of Honduras. She ran with the Libre Party, the party founded by her husband, José Manuel “Mel” Zelaya, not long after the coup d'état that ousted him from power in 2009. Castro promised a new future for Honduras after 12 years of National Party autocracy.

However, just a few months after taking office in January, the past has already cast a long shadow over the Castro administration. She pushed through an amnesty for allies of her husband accused of corruption, appointed former Zelaya officials to government positions, and placed several family members in key positions; provoking accusations of nepotism. Now an advisor to the president, Mel Zelaya is increasingly influential in the country’s politics.

By Leonardo Aguilar and Jennifer Avila

Photos by Fernando Destephen and Jorge Cabrera

Cover illustration by Donají Marcial

Former president José Manuel Zelaya was ousted from office 12 years ago, but he is back in the Presidential House once again as an advisor to his wife and current president, Xiomara Castro. Dozens of people enter the José Cecilio del Valle Palace every day hoping to meet Mel and voice their complaints and demands. Some come in hopes of getting a letter of recommendation from Mel for a government job. On March 18, however, Mel’s calendar only had one appointment. Without his wife present, he met late into the night with Enrique Flores Lanza, his former minister who had returned after a decade of exile in Nicaragua.

On the day Xiomara Castro was sworn in, Mel was handed the presidential sash that was snatched from him in 2009 when a coup overthrew him, and he was marched in pajamas at gunpoint to a flight out of the country. The Libre Party that he founded and now leads, put his wife in the presidency. Castro came to power promising a new future for Honduras after 12 years of the autocratic narco-state led by former president Juan Orlando Hernández and the National Party. Hernández was recently extradited to the United States to face drug trafficking and weapons charges.

However, instead of the promised fresh start, the first four months of the Castro administration have seen a return to the past. Besides Mel’s position as an influential advisor, several members of the Zelaya family have been appointed to key government posts. Just one week after her inauguration, Castro declared an amnesty for old allies of the Zelaya clan with pending legal cases, allowing them to return from exile abroad.

Flores was indicted on July 30, 2009 — one month after the coup — for falsifying public documents, abuse of authority, and fraud in a tax case in which former president Zelaya was also indicted. Zelaya himself benefited from an amnesty provision in the Cartagena Agreements that allowed him to return to the country in 2010. Jacobo Lagos, Zelaya’s chief of staff and manager of the Honduran Telecommunications Company (Hondutel), and Rebeca Santos, Zelaya’s finance minister, had their cases dismissed by the Honduran courts. Flores was also charged with abuse of authority, embezzlement of public funds, and usurpation of official functions for stealing US$575,000 from the Central Bank of Honduras.

A cartoon of a man pushing a wheelbarrow full of money out of the Central Bank on June 26, 2009, was seared in the public consciousness when it was widely disseminated in the media. Five years later, Flores confessed that the money he requested for the Presidential Honor Guard was actually used to pay for the Fourth Ballot Box scheme. Zelaya and his cronies wanted a public referendum on allowing a fourth ballot box in the general elections to be held six months later. They were seeking a constitutional reform to allow presidential reelection. The referendum was declared illegal by the Court of Appeals, excoriated by the mass media, demonized by the Church, and denounced by top military officials. The coup d’état followed soon after.

Contracorriente and the Redacción Regional journalism collaborative obtained the case file, which includes the testimony of a witness for the prosecution. A former Central Bank employee testified that the withdrawal was authorized by a signed note from Flores indicating that it was for expenditures related to the Presidential Honor Guard. The case file also documents a withdrawal of US$2.1 million on June 24, the eve of the referendum. When asked about the details of the June 26 withdrawal, the witness explained that they loaded wheelbarrows with 500-lempira bills and pushed them to the Presidential House; “We entered through the basement and took an elevator to Flores Lanza’s office. We left the money there.”

The Castro-backed amnesty decree erased the embezzlement evidence and all of the remaining charges against Flores. The president defended the amnesty, claiming that it protected political and social leaders who were persecuted for opposing the coup d’état. But it has also benefited at least three officials accused of corruption that are close to the Zelaya family.

Berta Oliva is the director of the Committee of Relatives of Detained and Disappeared Persons in Honduras (Comité de Familiares de Detenidos y Desaparecidos en Honduras – COFADEH), an organization dedicated to protecting human rights in Honduras. By law, COFADEH has an influential voice in the amnesty process. Oliva says that Flores and his lawyer, Milton Jiménez, provided a legal review of the proposed amnesty law that was ultimately approved. When questioned about Lanza’s involvement in developing a law that would personally benefit him, Oliva extolled Lanza’s record as a defender of human rights. Lanza’s lawyer made the same claim to COFADEH, who later formally documented this characterization of Lanza.

“He represented small farmer groups, and defended Renato, the journalist who was threatened in the 1980s, at no charge,” said Oliva, alluding to the threats against television news anchor, Renato Alvarez.

Though Mel’s former strongman has no official position in Castro’s administration, the influence of the president’s husband and several of his former officials is overwhelming. Rixi Moncada, who was Zelaya’s labor minister and manager of the National Electric Energy Company, is now Castro’s finance minister. Rebeca Santos, Zelaya’s finance minister is now president of the Central Bank. Edmundo Orellana, Zelaya’s defense minister, is now the minister of transparency. The list goes on. Edwin Araque, former president of the Central Bank is now president of another government bank—the Production and Housing Bank (Banco de Producción y Vivienda – BANHPROVI). Enrique Reina, a former Zelaya advisor, is now Castro’s foreign minister.

The Zelayas’ return to power is revealing their desire to complete unfinished business. In her final campaign speech, Xiomara Castro said that her mandate would be a continuation of her husband’s Citizen Power project that was cut short by the coup. She also promised a constitutional referendum. Mel still talks about how a group of military officials, business leaders, and coup-plotting politicians used his “Fourth Ballot Box” as an excuse to crush a nation “full of hope.”

On March 18, Zelaya welcomed Flores back to Honduras, and said, “Today one of the leaders of the Liberal Citizen Power government has returned. He was the coordinator of the Fourth Ballot Box and played a fundamental role in the transformation of Honduras.” Flores wore a white guayabera and sported a neatly trimmed beard at the press conference, discarding his tailored suits and clean-shaven look of the past.

The Zelayas’ relationship with the armed forces

After two weeks in office, Castro sent three of her closest relatives to a meeting with the Army General Staff, but Honduras’ first female commander-in-chief did not meet with the top brass of the army she commands. Representing her were three emissaries who share the same name. Defense Minister José Manuel Zelaya, a Zelaya nephew, led a delegation that included advisor José Manuel Zelaya Castro, the Zelayas’ son, and Mel, now as a presidential advisor.

The appearance of three people named José Manuel Zelaya acting in an official government capacity soon went from a curious coincidence to business as usual for a family sharing their newly-obtained power. Mel is a presidential advisor and their eldest child, Héctor Manuel, is his mother’s private secretary. Xiomara Hortensia, the younger daughter, is a congressional representative, and their youngest child, José Manuel, presents himself as an ad honorem advisor. Mel’s brother, Carlos Zelaya, is the secretary of the National Congress, and his son is Defense Minister José Manuel Zelaya. While this may look like nepotism, it is not illegal. These presidential appointments and the election of two Zelayas to the National Congress all fall within the bounds of Honduran law. Having such a tight-knit circle of power could be justified as a strategy for preventing another coup d’état.

“The armed forces have the weapons and strategies, so the president needs someone she can completely trust to oversee them,” said Edmundo Orellana, the former minister of defense under Mel Zelaya when he was ousted by the coup. When asked about his son’s new appointment, the former president’s brother, Carlos Zelaya, said, “We put someone we trust in that position because coups don’t take place without the armed forces.”

The defense minister is a 33-year-old lawyer who is holding a public office for the first time. Many party activists regard him as a technician rather than a politician. “He’s a specialist, especially in the area of communications,” said Marco Ramiro Lobo, the mayor of the Zelayas’ hometown of Catacamas.

Memories of the coup are still an open wound. When asked about trust in the ministry of defense, Edmundo Orellana said, “I was caught in the middle. The president trusted me but I don’t know if the military did. The problem grew to the point that it became unmanageable for me. Political and international pressure and pressure from organizations, civil society, private enterprise, and the churches … was so intense that it transcended what was an eminently military issue. There was a conspiracy against the president led by the National Party that involved virtually the entire government structure, including the armed forces.”

Arístides Mejía was Orellana’s predecessor as defense minister. He said the overthrow of Mel Zelaya was “a coup led by idiots because the country later completely collapsed. The problem could have been solved institutionally. The president didn’t control a single institution, unlike his predecessor who controlled them all. Mel didn’t control the courts, the armed forces, the attorney general, the electoral tribunal, the audit court, or even his own party. So what was everyone so afraid of?” asks Mejía.

General Romeo Vásquez Velásquez, the military leader who executed the coup is now retired. He made an unsuccessful attempt at becoming a politician and then wrote a book with his version of history. Sitting in an armchair in the living room of his home on the outskirts of Tegucigalpa, he lets out a chuckle when he looks at the photo of Mel with his son and nephew meeting with the top military officers. “The first gentleman… some people say he’s the first gentleman and others say that he snatched the presidency away from his wife, the elected president, who only uses the office as a defense mechanism. For me, there is one simple rule in the game of power—never show up your leader or your master, never overshadow your superior.”

Twelve years after the coup, the Zelayas are still afraid, or perhaps they are just protecting themselves.

Back at the ranch

In late April, Mel Zelaya disembarked from a helicopter that had landed at the El Aguacate airstrip, close to his family’s properties in the community of El Espino, on the outskirts of Catacamas. Olancho is one of the country’s largest departments, larger than the entire nation of El Salvador. It borders the departments of Gracias a Dios and Colón, both of which are primarily rural cattle ranching areas. They are also key drug trafficking routes. Sparsely populated expanses of land are ringed by mountains and jungle, and several nature preserves have deteriorated due to government neglect and incursions by drug traffickers.

Mel’s trip was for an extremely sensitive negotiation. Environment Minister Lucky Medina had promised to destroy an illegal road that cut through the Río Plátano Biosphere by the end of March. The road was constructed in a nature preserve designated by UNESCO as a world heritage site and provides cattle ranchers and indigenous people with a means of transporting their products from Gracias a Dios to Olancho. But locals claim that the road mostly benefits drug traffickers, so much so that they call it the “narco-highway.”

The road construction project kicked off in 2021, during former president Juan Orlando Hernández’s last year in office, and caused an uproar due to the extensive environmental damage that it entailed. However, construction of the road actually began in 2007, when Mel Zelaya was president.

No one is better suited to calming troubled waters in Olancho than Mel Zelaya, a local leader, and member of a family that is basically esteemed as local nobility. Property registers show that Zelaya owns several tracts of land in El Espino, on the road to the National Agricultural University. One property consists of 350,700 square meters of pasture land. Another measures 71,600 square meters and includes a house. A third property measures 64,500 square meters and also has a house. Lastly, he owns 488,000 square meters of fenced pasture land in the area.

In 2016, the Zelayas gave their son-in-law, attorney Juan Carlos Melara, 13,500 square meters of fenced pastures in the same area. Melara is the husband of their eldest daughter, attorney Zoe Zelaya, the only child that doesn’t hold public office. Melara was Zelaya’s assistant during the Citizen Power days, but Mel dismissed him in 2007 to “avoid” any semblance of nepotism.

When he was president, Mel donated property in El Espino to Teletón Honduras, a non-profit organization that raises money for disabled children, and donated money to build a classroom building at the National Agricultural University. Former president Porfirio Lobo Sosa of the National Party also donated money for a similar classroom building a few years later. Both buildings are tangible symbols of Olancho’s two landowning caciques and their respective political traditions.

Barely a month after the environment minister promised to destroy the controversial road, Mel arrived to negotiate with a delegation of cattle ranchers from the Moskitia region (Gracias a Dios department). The resulting agreement stipulated that the cattle ranchers would halt their extensive cattle ranching in the area if the government allowed the road to remain. A few days later, a group of Miskito leaders arrived in Tegucigalpa, demanding to be heard by the government.

“They should stop provoking the Miskito people,” protested Orlando Calderón, a member of MASTA, an indigenous Miskito organization. “The road crosses the river and goes all the way to Wampusirpi de Warunta where most of the narco-owned livestock ranches are located. If the military also starts invading our lands, they will grab land for themselves — there’s absolutely no control there.”

“We were happy when the minister said that the road would be destroyed to protect the area, and promised that the army would prevent land invasions,” said Calderón. But then Mel met with the cattle ranchers and agreed to preserve the road so they could use it to access their properties. Most of the cattle ranchers are from Olancho, and many represent people in high places.” And he’s not wrong. In Olancho, the Zelaya family are local nobility.

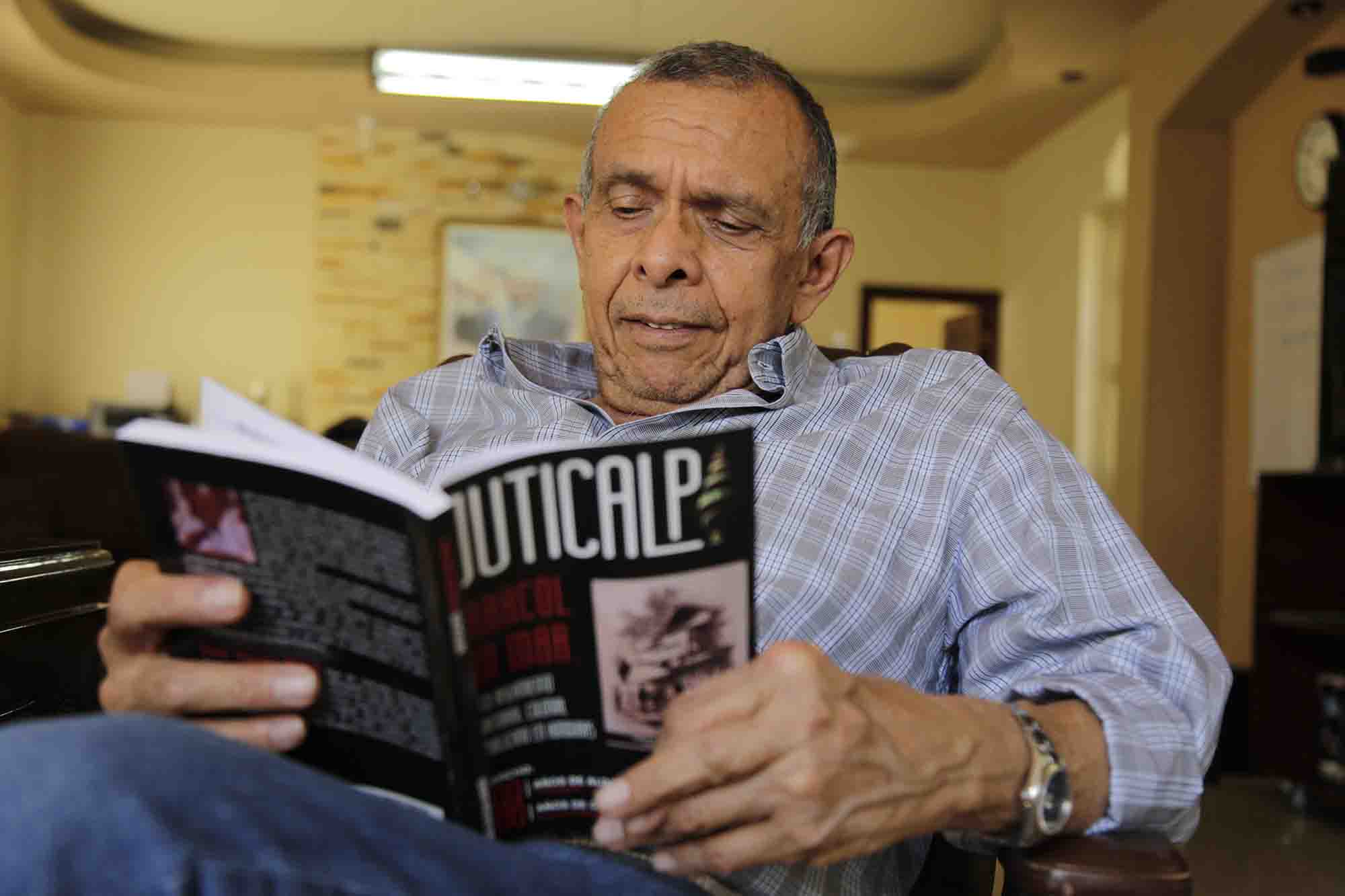

In the departmental capital of Juticalpa, a gray-haired man working in the city’s cultural center is intimately familiar with local history and the Zelaya family. Dario Euceda Roque is an author and former schoolmate of Mel Zelaya who worked as a speechwriter for Zelaya when he was president.

Euceda has researched Zelaya’s ancestry in Honduras and claims that it dates back to the Spanish conquest. “The first Zelayas [in the Americas] were three brothers; Santiago, Miguel, and Joseph. They first traveled from Spain to Mexico with the famous conquistador, Hernán Cortés. There is a city in Mexico called Celaya, spelled with a “C,” that they founded or conquered,” said Euceda.

When the Zelayas came to Olancho, says Euceda, they settled in the Lepaguare Valley of Juticalpa and asked the king of Spain to give them some land there. “The king granted them personal title to the property in 1536 as a reward for conquering foreign lands on his behalf. The Lepaguare Valley still belongs to them. I’m a lawyer and I can assure you that those property titles are legally valid.”

The Zelayas were always influential in Olancho, the largest cattle ranching area in Central America during the 18th century. According to Euceda, a Zelaya has always held some public office in Olancho; governor, mayor, or military commander. “In this century, two Zelayas have become president; Xiomara and Mel.”

But not everyone in Olancho supports Zelaya and Lobo. Sergio Antonio Campos, who ran for mayor of Catacamas as an independent, dubbed his campaign, “The Rat Catchers.” He complains that the Zelaya family “has been deified. People forget that before the coup there was an embezzlement scandal connected to the Fourth Ballot Box initiative. I believe that they gained a lot of followers by buying them off.”

People who have it all like to establish dynasties to preserve their wealth and power. Mel’s political success and his family’s current domination of the political landscape can be traced back to a push from his father, the first José Manuel Zelaya of Catacamas.

José Manuel Zelaya Sr. and Ortensia Rosales had four sons: Mel, the eldest, followed by Carlos (the current National Congress secretary), Héctor (murdered at a young age), and Marco, who married a daughter of former president Carlos Roberto Reina (1994-1998). The patriarch of the Zelaya Rosales family was convicted and imprisoned for participating in the notorious Los Horcones massacre of 14 religious leaders, campesinos, and students in 1975. Sentenced to 20 years in prison, Zelaya served little more than a year when he was pardoned under a general amnesty in 1980.

Deputy Foreign Minister Gerardo Torres, says that the Las Horcones massacre “is something that they [the Zelaya family] and Mel, in particular, will always have to deal with.” Torres doesn’t hold Mel Zelaya responsible for the sins of his father, pointing to “Mel’s denunciation of the secret Contra [Nicaraguan Resistance] base in El Aguacate, Olancho.”

Mel still owns the Los Horcones ranch in Juticalpa, as well as several lots in the city’s Castaño neighborhood where he spent his adolescence.

Mel Zelaya’s start in politics dates back to the 1980s, when a Liberal Party leader “fell from grace” and left a vacant seat in the National Congress. At the time, a close Zelaya relative named Armando Rosales was the National Congress secretary. According to Dario Euceda, Rosales said to Mel’s father, “Look, Benigno’s seat is vacant now, put Melito in there.” And Mel’s father agreed.

But Mel Zelaya needed a more powerful sponsor to become a national player in Honduran politics, and he quickly found one in Carlos Orbin Montoya, who became president of the National Congress after successfully guiding Liberal Party presidential candidate José Simón Azcona (1986-1990) to victory.

Mel does not forget old loyalties. In 2006, he returned the favor to Montoya by naming him Honduras’ representative to the Central American Bank for Economic Integration, and later as a director of the Central Bank. Montoya was one of the coordinators of the Fourth Ballot Box initiative prior to the coup.

Castro hasn’t forgotten either. In March, she appointed the 76-year-old political veteran as manager of Hondutel, the state-owned telephone company.

Mel Zelaya, the shrewd politician

Darío Euceda believes that Mel Zelaya’s main political talent is his shrewdness. “He sniffs out everything,” said Euceda. This was evident, said Eucenda, in his handling of a group of dissident Libre Party legislators during a dispute over control of the National Congress.

Mel has a tight grip on the Libre Party. Its statutes empower him to act as the party’s legal representative, general coordinator, president of the national coordinating committee, and a member of the party’s political committee. All decisions made by the party’s national coordinating committee or its national assembly must go through Zelaya. Since the party was registered in 2012, Libre has only had one legal representative and one general coordinator, who will hold those positions until 2025.

The Zelaya family founded and is fully invested in the party, much like El Salvador’s Bukele family and their New Ideas party. Besides Mel, Libre Party leaders include his wife, the president, his brother, his nephew, the minister of defense, and other government officials like the former mayor of San Pedro Sula, Rodolfo Padilla Sunsery (who also benefited from Castro’s amnesty by the dismissal of corruption charges against him); Finance Minister Rixi Moncada; labor leader and legislator, Juan Barahona; campesino leader and current deputy director of the National Agrarian Institute, Rafael Alegría; the current president of the Honduran Institute of Land Transportation, Rafael Edgardo Barahona; and legislator Beatriz Valle, who currently seems to be at odds with Mel Zelaya.

In the 2021 general elections, Valle and Jorge Cálix, widely recognized as the leaders of Libre’s M28 movement that Mel promoted when the party was founded in 2012, garnered more votes than any other congressional candidate in Honduran history. But after the dispute over the National Congress board of directors, some began calling them “traitors.”

But Xiomara Castro’s historic victory and Libre’s sweep in the congressional elections did not translate into party unity. Beatrix Valle thinks that they were victims of political jockeying that further strained frayed relationships. She claims that her relationship with Mel began to deteriorate when she decided to run for congress. “I noticed that Mel hardly spoke to me anymore, which I thought was strange. Just think, why would I start mistrusting Mel after 23 years? That never crossed my mind.”

Congressional leaders in Honduras often become viable candidates in future presidential elections. The landslide victories won by Cálix and Valle should have propelled them in that direction, but old quarrels and back-room political deals surfaced. And so, while Cálix tried to claim the top job in the National Congress with the support of Valle and other legislators, Castro was determined to stick to the political deal she made with the Salvador Party of Honduras in exchange for support of her candidacy. That deal included a Castro promise to back Luis Redondo of the PINU Party as president of the National Congress. When the dust settled, Redondo emerged victorious after Mel Zelaya met with Jorge Cálix in the Presidential House without Castro present.

More than 100 days after the rupture in the Libre Party, the Zelaya family has only grown stronger. Carlos Zelaya was appointed as secretary of the National Congress, a key operating function, and became the acting president of the legislature. Rafael Sarmiento, a close relative of the president, was appointed as head of the Libre Party congressional delegation. Beatriz Valle is among those who think that there was never any disagreement between the president and her husband, that it was all a skillfully planned strategy. She is convinced that the Zelaya family set a trap for her. “It was well-planned. They pushed us towards the edge by having Raúl Valladares [a well-known TV anchor] and other people close to Mel call me. “They gave us a little push by calling to ask us, ‘Are you still behind Jorge [Cálix]? Great! I’m with Jorge too.’ They did this so we would completely commit to Cálix,” said Valle.

With Cálix and Valle neutralized, a path opened up in the National Congress for the Zelayas’ third child—their daughter, “La Pichu.”

The clock is running fast in Honduras, especially since presidents are limited to a single four-year term. People in Catacamas and the corridors of political power are already speculating about the Zelaya clan’s next move, which might be the anointing of another Zelaya as Xiomara Castro’s successor.

On May 9, Dassaev Aguilar, the Castro administration’s director of public relations, tweeted a photo of himself with Hector Zelaya, Xiomara’s private secretary and son, captioned, “with the next president of Honduras.” Aguilar later backpedaled and explained that this wouldn’t happen in the next elections since it is prohibited by the Honduran Constitution.

One thing is clear—the political power of the Zelaya clan is strengthening and they do not want a repeat of what happened in June 2009.

COFADEH’s Berta Oliva says she doesn’t ever want to say the words “coup d’état” again and hopes history doesn’t repeat itself. But she believes that the forces that carried out the coup are still lurking behind the scenes. “Who removes and installs presidents? Who carries out coups all over the world? The United States,” she said. “What do the powers that be want? To demonstrate that Xiomara’s government is weak. That was their motive for criticizing the amnesty and the dispute in the National Congress. That’s why they say that Mel Zelaya is in control and is the real power behind the president. But if that’s the case and he succeeds in moving the country forward, what’s the problem? Under the [Juan Orlando Hernández] dictatorship, he had his brother in Congress, his sister was a minister, and another brother was a security advisor. He had his whole family in the government. Why wasn’t this considered a problem back then?”

Twelve years after the coup d’état, as he sits in a chair that looks tiny in his enormous house, General Romeo Vásquez analyzes the state of the nation, a nation that is now led by the same people who terrified him to the point that he preferred violating the constitution rather than allowing Honduras to turn into “another Venezuela.” Vásquez said, “They were able to come back and win easily because of everything that happened in 2009. They should be happy.” But he thinks that President Castro’s story may turn out differently. “She won because the people voted for her in a nice, democratic, and transparent election.”

However, the retired general is not happy. “They’re using the people’s political goodwill toward Castro to violate the law. That’s not why the public elected her—it was to solve the country’s most pressing problems. Yes, it’s still early in this administration and we should give them a chance. But as the saying goes: a leopard can’t change its spots.”

Editor’s Note: Despite multiple attempts at obtaining interviews with Manuel Zelaya Rosales, Xiomara Castro, Hector Manuel Zelaya, Carlos Zelaya and Xiomara Hortensia Zelaya, we did not get a response either directly or through the Press Secretary, Ivis Alvarado, to whom we submitted requests for interviews with the president, her private secretary and her senior advisor. “Time taken by the president to conduct interviews is better spent solving the country’s problems,” replied Alvarado. Josué Manuel Zelaya, the youngest son, refused to grant us an interview. We have been asking for an interview with Enrique Flores Lanza since the day he returned to Honduras. Although he was initially willing, he stopped answering messages on his private phone. We also contacted the Minister of Defense, José Manuel Zelaya, who requested that we submit a questionnaire and said he would respond via Whatsapp instead due to a health problem. After several reminders, the defense minister stopped answering his phone and never responded to the questionnaire.

*This article is part of Redacción Regional’s República Finquera journalism project to report on authoritarianism in Central America and Mexico. The project is an alliance of media outlets and journalists in the region, including Contracorriente.