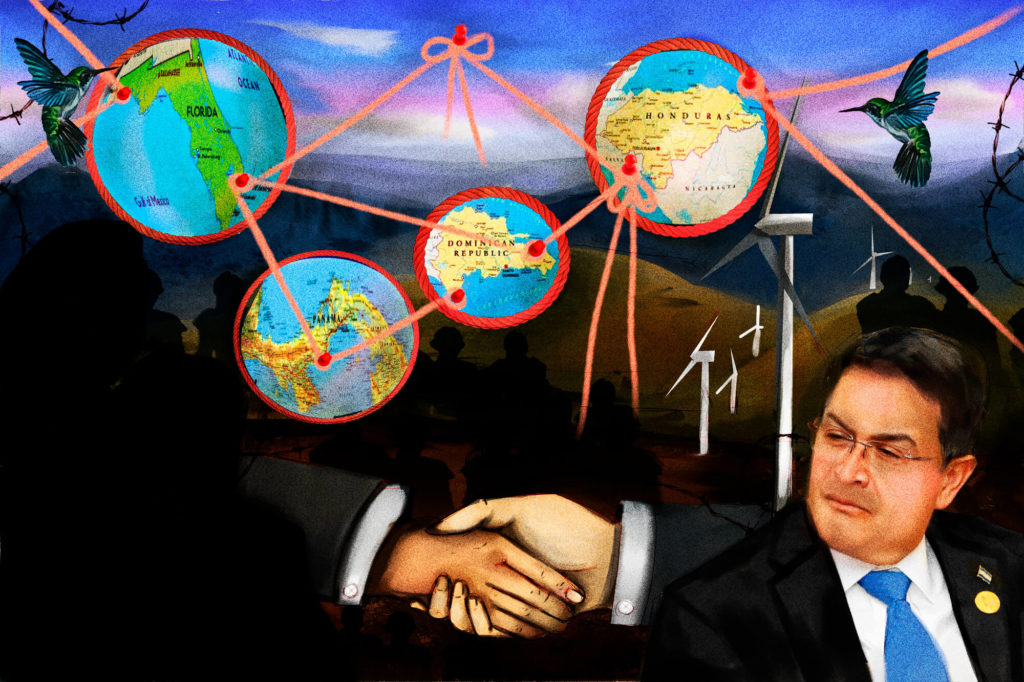

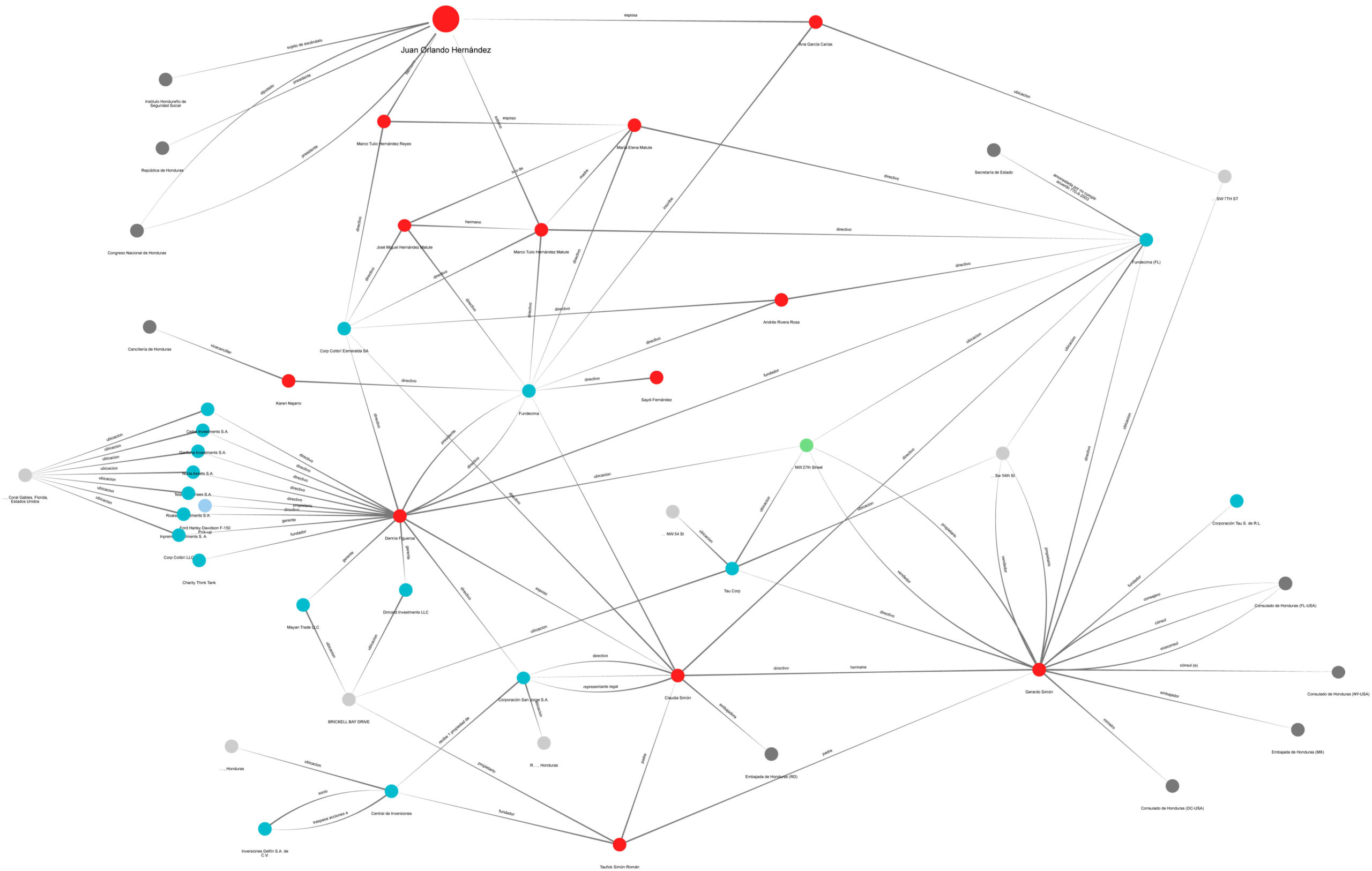

As detained former Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández faces extradition to the United States on three drug trafficking charges, this investigation examines a group of his relatives and friends, who have been partners for years in a maze of charities and companies in Honduras and Florida, multiple of which have no apparent business activity. The paper trail also leads to Panama. The associates – including the current Honduran ambassadors to Mexico and the Dominican Republic, a nephew of the former president, and a former financial consultant to the congress – told us that their ventures didn’t succeed due to a decade-old scandal involving one of their charities, Fundecima.

By Jennifer Ávila, Danielle Mackey and María Teresa Ronderos for Contracorriente and CLIP

In 2016, Claudia Simón de Figueroa, a professional event organizer and party planner, was appointed as the Honduran ambassador to the Dominican Republic by then-president Juan Orlando Hernández. Simón was already close to Hernández’s wife, Ana García Carías; around 2010, she began volunteering with García Carías to create the Criando con Amor(Raising Children with Love) program, according to Simón. Five years later, with Hernández in the executive, that program became part of the government under the Ministry of Social Inclusion (Secretaría de Inclusión Social – SEDIS).

Their husbands also had experience working together. Hernández, before taking the reins of the nation, was a legislator and president of the congress. At the same time, in 2010, Simón’s spouse Dennis Figueroa was a financial consultant to the congress, according to Figueroa, who now identifies as an independent financial consultant.

Figueroa and Simón gave separate interviews to this investigative team, comprised of Contracorriente and the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística – CLIP), with support from journalists and media outlets across the region. We followed the trail of a 2012 scandal that erupted around Fundecima, a Honduran non-governmental organization (NGO) directed by Figueroa, in which police at a routine checkpoint stopped a pick-up registered to Fundecima, and discovered in it the wife of the Minister of Finance and a stack of more than $40,000 in local currency. At the time, Fundecima representatives rushed to explain that they were in the process of selling the truck to the minister, Hector “Tito” Guillen. A subsequent media frenzy, sparked by the prominent positions of the people involved, raised questions about the source of the money and the relationship between Fundecima and the government. The Honduran Attorney General opened an investigation but eventually removed Fundecima from the case, even though the organization failed to submit required financial statements to the government. Now, ten years later, it is clear that the inquiry left loose ends.

Our team uncovered documents proving that Fundecima was established by García Carías, former president Hernández’s wife, acting as attorney for Dennis Figueroa. We also discovered a second Fundecima in the United States. The U.S. non-profit, which appears to have never operated as a charity, was founded by Figueroa, his wife Claudia Simón, and her brother, Gerardo Simón, currently the Honduran ambassador to Mexico, along with their lifelong friends who are part of the Hernández family.

The members of that group appear on the boards of directors of multiple other companies and charities in Honduras and the United States. Simón family residences repeatedly occur on public documents as the businesses’ U.S. addresses. Various of the entities never showed any activity – as is the case with six companies that Figueroa founded on the same day in Panama.

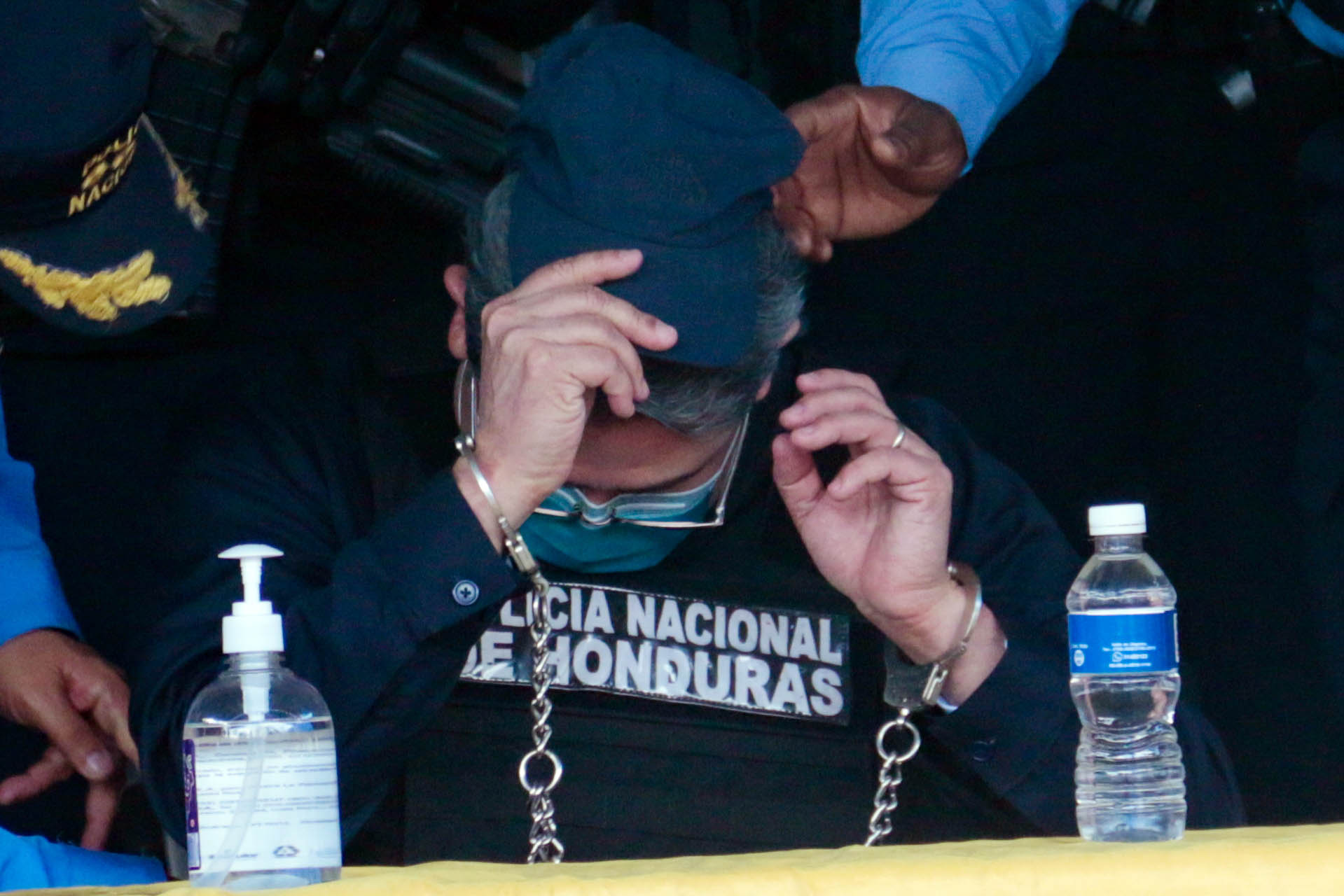

In 2022, after eight years as president of Honduras, Juan Orlando Hernández left office on January 27 and was made a representative to the Central American Parliament (Parlamento Centroamericano – PARLACEN). Less than two weeks later, the U.S. State Department declassified a designation it had made in July 2021, when it added Hernández to the Engel List of “corrupt and undemocratic actors” who engaged “in significant corruption through fraud and misappropriation of public funds,” rendering him ineligible for visas and admission to the U.S. On February 14, the U.S. government submitted a request to the Honduran Foreign Ministry for extradition of the former president on three drug trafficking charges.

In this context, the discovery of this group of companies and people – which includes two ambassadors, a former congressional financial advisor, and, in one case, the former first lady – raises new questions about the firms’ purposes and activities.

“I’ve created many companies. Some have worked out and others haven’t,” Figueroa told this journalistic alliance. “Some were incorporated but never actually operated. Fundecima was established as a charity, but we couldn’t accomplish what we set out to do.”

The Simón siblings made similar claims, as did Marco Tulio Hernández Matute, a nephew of Juan Orlando Hernández, who was on the boards of directors of some of these entities, including Fundecima.

It was necessary to establish a second Fundecima in the United States, Figueroa said, in order to fundraise for charitable activities in Honduras. His brother-in-law Gerardo Simón, who was a diplomat in Florida at the time, joined in that effort.

Simón has accumulated twelve years in the foreign service, beginning with his 2010 nomination to head of commercial affairs at the Honduran consulate in Miami, under President Porfirio Lobo in the first administration after the 2009 coup. Simón was soon promoted to vice consul in Miami, and later made consul in 2014. After a brief assignment at the helm of the consulate in New York City, in 2019, he was made a minister at the Honduran embassy in Washington, D.C. In April 2020, Simón was appointed Honduran ambassador to Mexico, where he currently serves. He became a member of the board of directors of Fundecima in Florida while a full-time diplomat.

Fundecima’s Miami directorate also included the former president’s sister-in-law, María Elena Matute de Hernández, a former judge. Her son, Marco Tulio Hernández Matute, also sat on the board. Public records show Fundecima’s Florida address as Gerardo Simón’s house, and when Simón moved, Fundecima’s base did too. In an interview, Simón insisted that he was never involved with Fundecima or any other of the group’s companies, even though he was listed on its board of directors. He lent his name and address, he said, as a favor to Dennis Figueroa.

Fundecima, the charity with big names and without a clear mission

Marco Tulio Hernández Matute, Claudia Simón and Dennis Figueroa have known each other since they were children, when they were students at the American School in Tegucigalpa. Their longstanding family ties make it unsurprising that they would attempt to go into business together.

According to Hernández Matute, after Figueroa’s sister Cynthia Marina was killed in a car accident, they decided to christen a charity with her name. In 2006, they established the Fundación para el Desarrollo Comunitaria Cynthia Marina (Cynthia Marina Foundation for Community Development – Fundecima), and it was registered by the lawyer who would later become first lady, Ana García Carías.

The organization’s objective, said Hernández Matute, was to promote “development in the Cerro de Hula community through financial assistance for women.” Cerro de Hula is the point of highest elevation in the municipality of Santa Ana, a few kilometers from Tegucigalpa, and is the current center of production of wind energy in the country.

However, Dennis Figueroa and Claudia Simón told us that Fundecima’s mission was to support bilingual education for girls, because Figueroa’s deceased sister, the foundation’s namesake, was a private school teacher who sponsored scholarships and supported girls in rural impoverished areas. Fundecima was created to continue Cynthia’s efforts, the couple said. Figueroa claimed that the organization strayed from its original purpose of education into very different areas, like wind energy, as a way of raising money for the girls.

The earliest available records pertaining to the Honduran Fundecima date to 2010, and indicate that, in addition to the three lifelong friends, its board of directors included Hernández Matute’s mother, the former judge, and his brother, José Miguel Hernández Matute. Dennis Figueroa’s parents were also on the board. Additional directors have included Saydi Fernández and Andrés Rivera Rosa, private citizens who have never held public office.

Also on the Fundecima Honduras board was Karen Najarro, a confidante of former first lady García Carías and currently the country’s vice-minister of foreign relations. Earlier in her career, Najarro was an official in the Vida Mejor (Better Life) program, a signature initiative of the Hernández administration, and later became an official in the Ministry of Social Inclusion (Secretaría de Inclusión Social – SEDIS). Najarro did not respond to interview requests via Whatsapp messages and phone calls.

In December 2010, four years after the founding of the Honduran Fundecima, a second iteration of the foundation appeared in Florida, with many of the same members of the board of directors and the notable addition of Ambassador Gerardo Simón. Figueroa told us that the group needed to create a U.S.-based Fundecima to receive school supplies for the girls. “Several American companies offered to make donations. We had already identified $300,000 to $400,000 in donations,” said Figueroa.

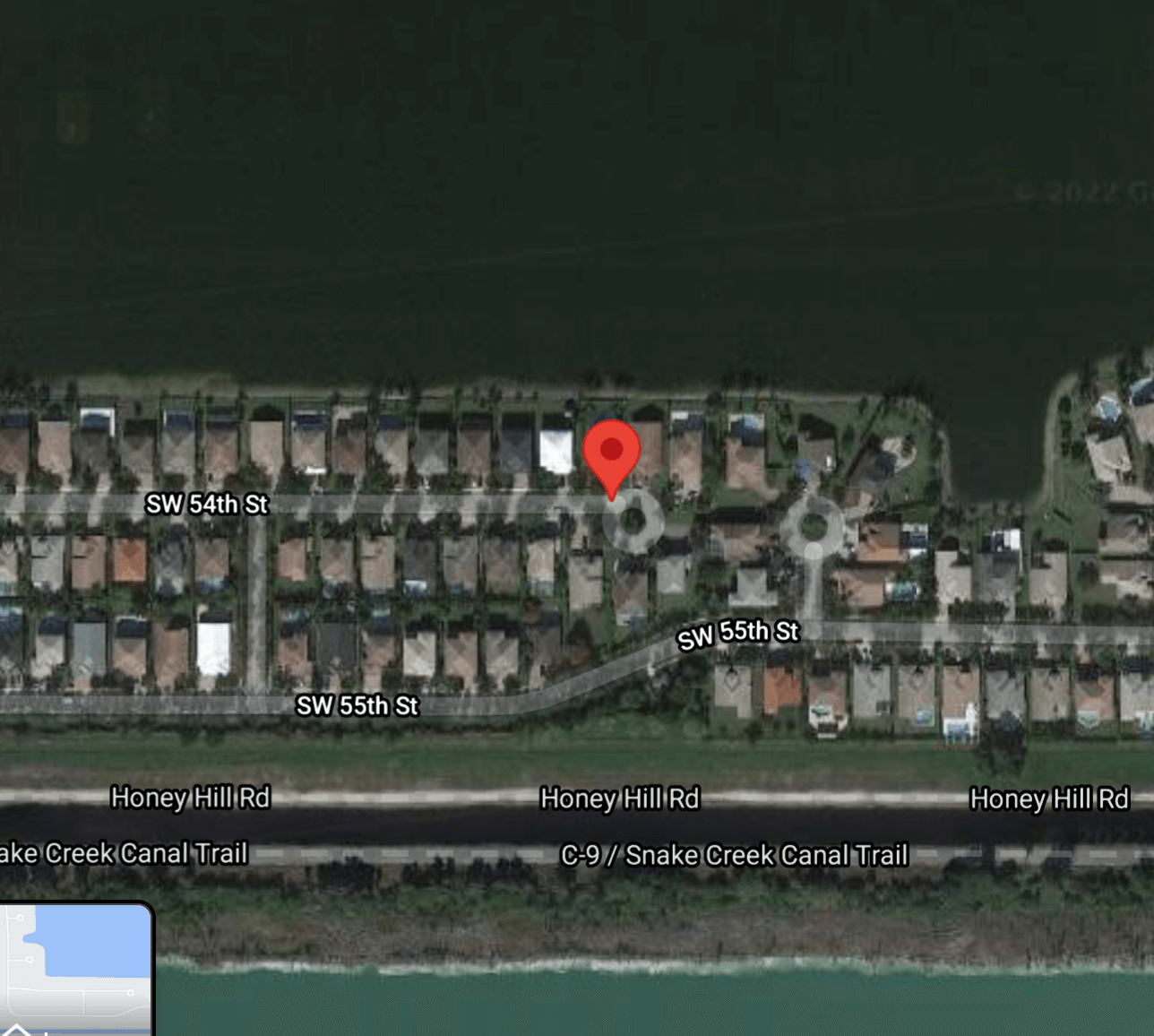

Fundecima’s first U.S. address was a lakefront home on Southwest 54th Street in Miramar, Florida, in the house where Gerardo Simón lived while vice consul. He had purchased it for $468,000 with his wife, Ana Hasbun, and lived there for a year.

That same year, Juan Orlando Hernández and García Carías tried unsuccessfully to buy a property in Florida. According to public documents, they made a down payment on a Marriott Resort timeshare in Villas at Doral, but when the additional installments went unpaid, they were sued, and the couple appeared to have lost their investment.

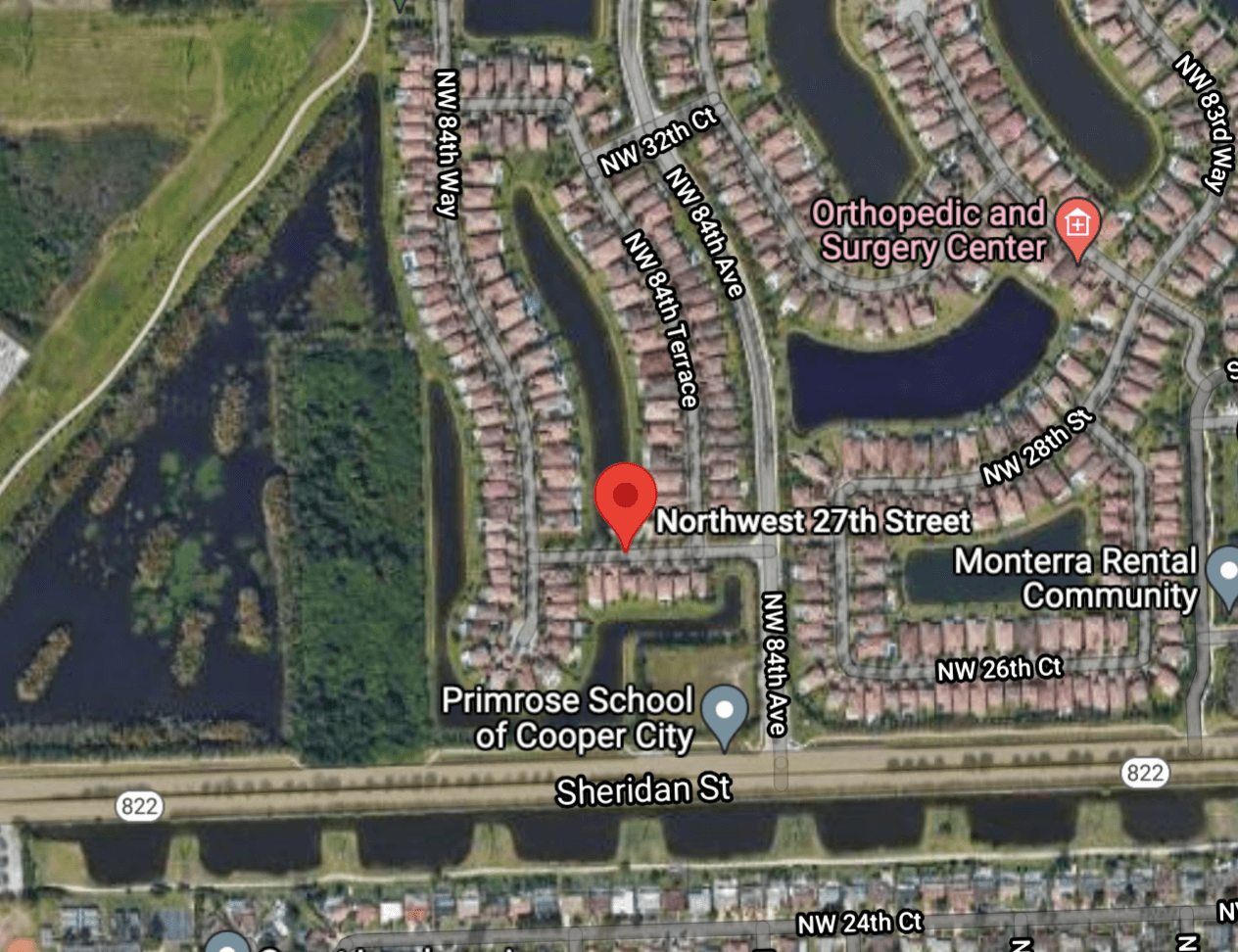

Public documents show that Fundecima Florida was inactive for more than a year, and then reactivated on May 21, 2012. It moved to another location, about 13 miles away, on 27th Street in Cooper City. This new location was an upscale Broward County residential complex called “Monterra,” in a home that, on December 30, 2011, Gerardo Simón and his wife had purchased for $554,000.

Diplomat and first lady, neighbors

In June 2013, Ana García Carías also bought a house in Monterra. It was mere months before her husband won his first term as Honduran president, during a campaign that was later revealed to have been pumped with illicit money. Some of the illegal contributions came from public funds embezzled from the Honduran Social Security Institute (IHSS), a fact later admitted by Hernández himself. At least $2.6 million more was drug money, according to the U.S. Department of Justice, information that didn’t become public until years later during the trial of Hernández’s brother, Juan Antonio “Tony” Hernández. According to U.S. authorities, one million dollars of those narco proceeds were a bribe to the Hernández campaign from Mexican drug lord Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán.

Hernández’s wife, García Carías, paid $804,586 for the house in Monterra. It was located just a one-minute drive from Gerardo Simón. For four years, they were neighbors.

In June 2017, the Simóns sold their home for $650,000. In the public record of the sale, signed by the couple, they declared their new residence as a luxury apartment in Miami, located on Southwest 7th Street and now worth $757,000. At that time, the apartment was owned by a company registered in the British Virgin Islands called Hacock Invest & Trade Limited.

A year later, in October 2018, García Carías also sold her Monterra house, for $880,000. In the public record of that sale, she declares her new residence as the same luxury apartment on Southwest 7th Street, still owned by the company in the British Virgin Islands. Hacock, which had bought the apartment in 2016, sold it in 2019.

Gerardo Simón acknowledges renting an apartment in that area, but denies ever sharing an address with García Carías. He also denies knowing anything about Hacock, the company in the British Virgin Islands. García Carías received our questions about the apartment and her close relationship with the Simóns and Fundecima via her assistant, but offered no response.

On November 23, 2018, one month after García Carías sold the Monterra house, her brother-in-law Tony was arrested on drug charges at the Miami airport. The U.S. Embassy in Honduras immediately announced that he would be prosecuted in a federal court in New York City.

About two months later, Gerardo Simón was assigned to the Honduran Consulate in New York City, a position he held until June 2019.

Fundecima, the charity that doesn’t seem to help anyone

From 2010 to 2012, Fundecima was a registered organization in Florida, but Honduran activists in Miami heavily engaged with their ex-patriot community say that the organization never provided any services. One told us that it seemed to be a shell company. “I assure you, as a Honduran in Miami, that it doesn’t exist,” said another.

In fact, Ambassador Gerardo Simón confirmed this. “It didn’t do anything,” he said in a telephone interview conducted in Mexico by a collaborating journalist with this team. Simón said he had nothing to do with Fundecima. Nevertheless, he went on to offer details; for instance, he said, the Florida Fundecima had no connection to its Honduran counterpart, nor did it open any bank accounts, he said. Although he claimed it was not a tax-exempt foundation, public documents clearly indicate that it was a 501(c)(3) organization, which is the U.S. tax code designation for a non-profit entity. Simón also said that he personally closed down Fundecima Florida.

“I’m a person who will take my good name, above all, to the grave, and I have no connection to any of these companies at issue,” said Simón in the interview. “That happened ten years ago. Since then I’ve realized that I may have been very young then, and discovered that sort of thing isn’t for me.”

Gerardo Simón and Dennis Figueroa both claimed that Fundecima Florida only existed for six months, but public records indicate the foundation was active for two years. For her part, Claudia Simón claims that she didn’t know anything about the U.S. Fundecima, even though she was on its board of directors.

“I didn’t even know there was a Fundecima in Florida,” she said. “It was founded here in Honduras to collect aid for the girls I’ve been supporting for a long time,” she said. After hesitating, said that maybe she did know about Fundecima Florida, but was never involved with it. “I had no connection with that company. I had my hands full with the one here,” she said, “with trying to collect a few resources. I mean, I was the one who was always putting myself out there to help these girls. That’s how Fundecima started.”

The three friends insist that Gerardo Simón had no active role in Fundecima Florida, and the ambassador himself claims the same. “Since I was the commerce official in the consulate at that time, my brother-in-law asked for my home address to create it, but to say that I founded, operated, or directed the organization— no, never, in no moment.” He says that he has always been careful not to mix his business activities with his diplomatic career.

In addition to serving as Fundecima Florida’s address, Simón’s home was the registered base for a for-profit company called Tau Corp, founded in 2007 by Simón and his wife for business activities. Although Tau Corp is no longer active, it filed reports to the state of Florida from 2009 until April 30, 2013, two months before Honduras’ new Diplomatic and Consular Service Law took effect, which prohibited diplomats and consular officials from “conducting professional or commercial activities for their own benefit in the same country where they represent Honduras.” After having directed Tau Corp for three years, in June 2013 when the new law entered into force, he created Corporación Tau in Honduras and closed the Florida company. Simón cites this as an example of his respect for the law, saying that he did that at the recommendation of the U.S. State Department.

The Simón siblings said their family wealth has been accumulated over many years. But it is impossible to know whether the diplomats declared the earnings they made during their years of public service, because this information is cataloged as classified in Honduras by the Superior Court of Audits. We filed a motion before the Constitutional Chamber of the Honduran Supreme Court challenging this classification, but it awaits resolution.

Gerardo Simón furthermore said that he has never been involved in companies accused of corruption, and that he was not implicated in the Honduran government’s investigation of Fundecima.

The aforementioned investigation – after one million lempiras in cash were seized in the truck connected to Fundecima – meant that the promised donations never arrived, according to Figueroa. “We ended up just spending money on starting up the foundation over there,” he says, “because then the incident occurred.”

Open questions remain after the one million Lempiras

It was July 31, 2012, when Dinora Suyapa Aramburi López, the wife of then-Minister of Finance, Héctor “Tito” Guillén of the National Party, was detained by police with the equivalent of more than $40,000 in cash. She was riding in a Ford Harley Davidson F-150 pickup that Fundecima representatives said they were selling to Guillén for 1.25 million lempiras, more than $50,000. Guillén had not fully paid for the truck, according to a document that Fundecima’s lawyer presented to the press and the Attorney General. Two months later, on September 19, 2012, Figueroa dissolvedFundecimaFlorida.

At the time, Juan Orlando Hernández was president of the congress and was a presidential candidate in the 2013 elections.

When the news first broke that the Finance Minister’s wife was found with cash in an extravagant truck, the connection to Fundecima wasn’t yet known. The journalist who made that connection was named Ariel Da Vicente. After his story ran, Da Vicente received death threats against himself and his family, and was forced into exile for a time, according to a source close to the case. Da Vicente died of cancer in December 2021.

In a hearing during the investigation into the money and the Ford, Guillén, testifying in his own defense, denied Da Vicente’s reporting and said that he took no action against the journalist. “Trash doesn’t merit much attention in this country,” he declared. “Someone makes defamatory accusations, and TV reporters just seize on it.”

In 2013, the Special Prosecutor for Transparency and Against Corruption (Fiscalía Especial para la Transparencia y Contra la Corrupción – FETCOP) charged Guillén with fraud and abuse of authority. He was forced to resign, but in 2014, the charges were dropped. Guillén subsequently disappeared from public life; he last appeared in the press when he attended a 2016 meeting convened by the mayor of San Pedro Sula. Attempts to contact Guillén failed because his cell phone number is inactive.

Alongside the fraud case, the Special Prosecutor for Organized Crime opened an investigation into money laundering. The officials were interested not only in the source of the cash but also the vehicle in which the money was found, according to case documents. And, given the fact that the truck was mid-transaction, not yet fully sold to the minister, investigators also looked into Fundecima.

In Honduras, civil society organizations must register with a government agency, called the Dirección de Registro de Sociedades y Asociaciones Civiles de Honduras – DIRRSAC, to which they must submit regular financial reports. The DIRRSAC then maintains a file on each organization. In response to two freedom of information requests filed by this team, in 2019 and 2020, the DIRRSAC provided only four documents on Fundecima: its original registration, its boards of directors from 2010 to 2016, its explanation of a failed 2013 project, and its request for its own dissolution in Honduras in 2016. Fundecima’s file itself was missing, including the required financial reports.

But a page included among the documents listed all of the officials who had reviewed Fundecima’s file over time. The last person on that list was Jorge Montes, the DIRRSAC director. InSeptember 2020, the DIRRSAC clarified to us that Montes had checked out the file and never returned it. We interviewed Montes, but he refused to discuss the matter.

Fundecima’s missing financial reports were also established in the 2012 press coverage of the scandal. Of course, such information would have been key to investigating suspicious money movements. In 2013, the Ministry of Interior and Justice issued a list of civic organizations sanctioned for failing to submit financial reports, and it included Fundecima.

According to minutes from a Fundecima board meeting that were among the documents gathered in the investigation, on February 28, 2011, the board approved Figueroa to purchase a vehicle for use by the foundation. He bought the F-150weeks later, in April, from a Ford dealership in Tegucigalpa. One year later, he sold the vehicle to Guillén, alleging it was too expensive for the foundation, via a promissory note that specified the truck would be paid in two installments. Guillén testified that Figueroa had offered to sell him the Ford during one of their many conversations in Congress. The cash and the truck were seized by the government as part of its money laundering investigation.

In August 2012, an attorney representing Fundecima requested his client’s removal from the investigation, arguing that the purchase and sale of the truck had been duly documented. In 2019, the court responsible for confiscations determined that the only remaining asset of unknown origin was the cash found in the vehicle. As a result, the F-150 was returned and Fundecima was removed from the case.

Many questions remain. If Fundecima did not submit any financial statements to DIRRSAC since 2012, why didn’t the Honduran government shut down the foundation, in accordance with Article 26 of the Special Law for NGO Promotion (Ley Especial de Fomento para las ONGs)? Enacted in 2010, this law states that failure to comply with financial reporting requirements will result in the termination of an organization’s legal status. And, if the Fundecima directors argue that their charity work was unviable because they were unable to raise money, how were the foundation’s coffers empty if it had bought and sold a lavish vehicle?

When Fundecima filed for dissolution in Honduras, in 2016, it claimed that its donors and partners had backed out. Fundecima, an organization whose stated purpose was to help low-income girls with bilingual education, bizarrely claimed in that filing that its last active project was a 2013 consultancy to create an urban development plan for one of the largest cities in Honduras, Danlí. The document stated that its contract for the consultancy was canceled because the investigations into the incident with the truck damaged Fundecima’s reputation.

The urban development project it described indeed existed, and was financed by the World Bank through the Honduran Social Investment Fund. But Fundecima does not appear among the project’s registered bidders nor on the list of subcontracted consultants. (The project was awarded to Informes y Proyectos, a company that has no apparent relationship with Fundecima or Figueroa.)

In his testimony during the investigations, Dennis Figueroa had claimed that he derives most of his income from Inversiones de Centroamérica, a company he has owned since 2000. He also said that he has a master’s degree in marketing and thus provides consulting services to private companies.His descriptions of exactly what Fundecima did only raised more questions: He said that the foundation raised funds from members, signing contribution agreements with private entities like the corporate giant Tabacalera Hondureña, a tobacco company in San Pedro Sula that is a subsidiary of British American Tobacco, and that it also earned income from clean energy projects.

“We have never received any money from the government,” Figueroa told investigators. He continued, confusing the matter of Fundecima’s identity even further: “The foundation’s main objective is to support small, medium and large enterprises in increasing their job-creation capabilities, to carry out marketing for projects, clean energy generation, gender equality analysis of community projects, and we were in the process of getting into exporting agro-industrial and artisanal products for small and medium producers, but then came this unfortunate event that linked us to this investigation.”

Figueroa’s statements then, of course, contradict what both he and his wife said in our interviews, that Fundecima was dedicated to helping young girls. And, despite the 2016 application for annulment, no public documents thus far confirm that the foundation was actually dissolved in Honduras.

Hernández Matute lamented what he saw as the investigation’s impact on the foundation. “Fundecima had just started up when all this happened, and it closed all doors for us. We had obtained funds from a private transnational company, and the car was in the name of the foundation because we had to capitalize on it,” he told us, adding, “And Tito [Guillen] did pay for the car.”

The inability to fundraise after the scandal is why they decided to close the Florida location so quickly, Figueroa said. “We clarified everything to the press, and especially to the Attorney General,” he said. “People say all sorts of things, but the fact remains that the damage to our reputation prevented us from moving forward.”

Dennis Figueroa is not a public official, but is well known in the National Party. Three high-level sources confirmed to us that he was close to former president Hernández, an advisor of sorts, and that he was involved in financing political campaigns for the National Party.

Figueroa categorically denies this. “I have never managed any National Party money, absolutely not. What is true is that I have a very good relationship with the business sector due to my consulting and entrepreneurial activities, and I have participated in meetings in which businesspeople have made donations to the party.”

Figueroa also said that he no longer does consulting for the public sector. “After that mess with the car, I stepped away from all activities involving the government,” Figueroa said, adding, “My mom suffered a lot because the incident marred my sister’s name. That made me realize that I don’t want anything to do with it. I have kept my word, have tried to make our country more transparent, and I have suggested ways of involving civil society, but no one has listened.”

Fundecima is not the only prominent Honduran entity founded by this group of people close to former president Hernández. Nor is it the only one with a questionable mirror company with an identical name in Florida.

The Colibrí Group

In Honduras, the Figueroa and Hernández families have been known as the Colibrí Group, due to their association with Corporación Colibrí Esmeralda, a company created in 2004 in Tegucigalpa by Figueroa, in representation of another of his firms, Inversiones CD. Other partners include his wife Claudia Simón, in representation of her then-four-year-old son, and Marco Tulio Hernández Reyes, who is the brother of former president Hernández and father of Hernández Matute. Indeed, also among the partners are both Marco Tulio and his brother, José Miguel Hernández Matute, along with Andrés Rivera Rosa.

This list is almost identical to Fundecima Honduras and Florida, and they are all people close to former president Hernández.

Colibrí’s purpose was to develop wind energy projects, said Hernández Matute, like Fundecima, although he clarified that they meant the entities to perform different functions in that sector. Public documents show Colibrí’s designated business activities as renewable energy project development, consulting in engineering, architecture and urban development, and the sale and purchase of real estate. ]

But Colibrí’s name does not appear in any of the approved contracts in the renewable energy sector in the country, according to public records. Nor has it ever had any government contracts.

Hernández Matute claimed that Colibrí never pursued a project in the country’s center of wind energy production, the Cerro de Hula region, because they prioritized other business ventures over this one. “I’ve closed that chapter of my life,” he said.

Hernández Matute also brought up several other Honduran companies in which he was involved with Dennis Figueroa and Claudia Simón. One, Comunicaciones Allegro, was founded in 2004 by Figueroa’s company Inversiones CD, and which, as an entity, became a Colibrí shareholder in 2005, along with Hernández Matute. Allegro was supposed to be a content provider for telecommunications companies like Tigo, and it too failed, said Hernández Matute, because of evolving technology.

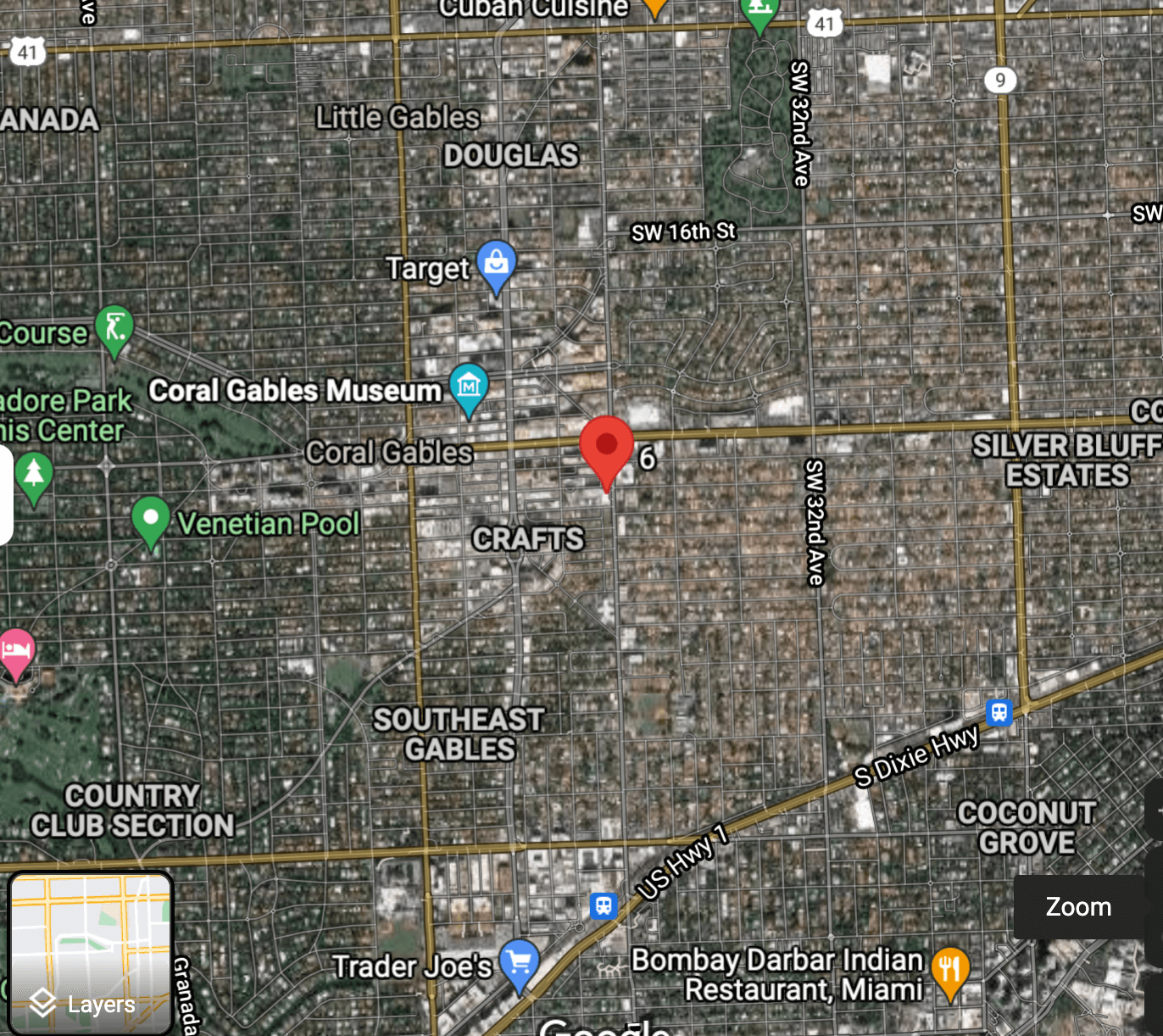

Just as with Fundecima, Figueroa created a second company called Colibrí in the United States, registering Corp. Colibrí, LLC in Miami on December 12, 2008. The only named director was Figueroa, and there was no board. Colibrí registered its domicile to an address in Coral Gables, Florida. In 2011, Figueroa filed to dissolve the company.

In Florida, Colibrí had “various functions, but all in the area of financial consulting,” Figueroa said. “It worked for clients who were American companies, so we opened the LLC. But this had nothing to do with the Simón family,” he said, referencing both his wife and brother-in-law, the diplomats. “I am Dennis Figueroa and those were my financial consulting activities.”

The Honduran Attorney General’s office, while investigating Fundecima, also attempted to look into Colibrí. It formally solicited asset declarations and criminal records for “Grupo Colibrí de Honduras,” “Fundecima,” and “Fundeciman,” but its search came up dry. When prosecutors asked Figueroa directly if he had any relationship with “Inversiones Colibrí de Honduras,” Figueroa replied that he did not. The prosecutors presumably meant to ask about Figuera’s company, Corporación Colibrí Esmeralda, and to conduct document searches by the full, proper names of Colibrí and Fundecima, instead of the acronyms and erred-but-similar names it solicited. The investigation ultimately produced no findings.

Hernández Matute blamed the group’s multiple inoperative companies on the scandal with the cash in the truck, which, he alleged, was orchestrated to discredit Juan Orlando Hernández while he was positioning himself to become the National Party’s candidate for president. He also said that being related to Juan Orlando “has constrained and hurt us.”

Figueroa claims that, in Honduras, Colibrí did operate for a while. “I did financial consulting with that company,” he said. “You might think it odd that the company never did anything in the field in which it was registered to work. The influence that I supposedly had with people in the National Party clearly never materialized,” he said. He continued: “Colibrí Honduras was created after a study on wind farms in the Santa Ana [region], and we applied for a wind farm concession during the Ricardo Maduro administration [2002-2006], but another company was awarded the contract. We were unsuccessful with the undertaking, so the company later became inactive. But I liked the name, so I used it to provide consulting services, and I made it function and grow.”

In addition to Colibrí, Figueroa has founded more apparently inactive firms in Miami and Panama.

Figueroa’s other companies abroad

In 2007, Figueroa created two limited liability corporations in Miami, Mayan Trade and Dimond Investments. Both were dissolved in 2008. Neither company identified a board of directors or any other management, but both listed their headquarters as the same address on Brickell Street, which is an apartment owned by a Simón family firm in Honduras called Central de Inversiones. The board members of Central de Inversiones include Gerardo and Claudia’s late father, Taufick Simón Roman, and in 2019, the company transferred all of its shares to another Simón company, Inversiones Delfín. At that time, both siblings Gerardo and Claudia Simón were active diplomats serving abroad, and they also appeared alongside Figueroa on the board of a second Honduran firm, Corporación San Jorge, which had received assets from Central de Inversiones.

In Miami, Mayan Trade was created to “export nostalgic products,” said Figueroa. (Such products might include traditional bread, cheese or coffee sought by the Honduran diaspora living abroad.) Figueroa explained this company’s apparent inactivity by saying it failed because he was too busy with his other companies. Meanwhile, he established Dimond Investments as a holding company, “the owner of all the other companies,” he said, “but I wasn’t able to do it, I never used it.”

Figueroa said he derived no benefit from starting several business ventures in the same city where his brother-in-law was the Honduran consul. “There is no connection between the Simón siblings and these companies,” he said.

In September 2014, when Juan Orlando Hernández was nine months into his first presidential term, Figueroa created another perplexing venture in Florida, a company called Charity Think Tank. Despite its name, this was a for-profit company, and its directors included Figueroa’s son, Andrés, and two men named Juan Camilo Jaramillo and Nicolás Hoyos. The company’s address was the Center for Innovation and Economic Development (CIED), a business incubator that aids entrepreneurs in setting up new ventures, at Santa Fe College in Gainesville.

When contacted by us, a CIED representative recalled the efforts to help Figueroa start Charity Think Tank. The representative specifically recalled Figueroa saying that he was close to the president of Honduras.

Charity Think Tank’s purpose was never clear, said the CIED representative, who asked for anonymity. Figueroa had told them that he wanted to create a support network for start-ups. The idea was to manage competitions in which participants would pitch new companies that benefited charitable causes. In the process of helping Figueroa, one of the center’s employees wrote an email to another, which read: “I am a bit puzzled by this one. There is no business element,” according to the representative, who shared its contents with us. “We didn’t have a very active role with them,” the representative told us. CIED’s last contact with Figueroa and his team was in June 2015. Charity Think Tank was shut down in September 2015.

When we interviewed Figueroa, he said that he wanted Charity Think Tank to support young entrepreneurs. “Like Fundecima, it didn’t have bank accounts or operate at all, except for events with universities and college students to promote youth entrepreneurship,” he said. “It did not engage in any commercial or fundraising activities.”

There are more companies in Panama. On a single day, March 10, 2008, Figueroa created six firms there: Inprema Investments, Nuria Assets, Tela Enterprises, Ceiba Investments, Roatan Investments, and Garifuna Investments. In addition to Figueroa, two other people appear as founders, named José Anael Reyes and Jonathan C. Davis. The address for all six companies is the same Coral Gables location to which Figueroa would register Colibrí Florida six months later.

According to Panamanian public records, the required taxes and fees on all six firms went unpaid for three years straight, and thus they were suspended. T&T Asociados, the law firm acting as their registered Panamanian agent, dissociated itself from them between late May and early June 2020.

Figueroa denied having any active firms in Panama. “I founded one or two companies and never used them, so they closed. I don’t have any companies in Panama now, nor were there active boards of directors, much less bank accounts,” he said. He had intended to use the Panamanian firms as holding companies for his other companies, but it turned out to be too expensive, he said.

Both Figueroa and Hernández Matute repeatedly decried the Fundecima scandal as the reason their businesses did not succeed. Both said that scandal was politically-motivated. Figueroa also claimed that, at the time the Ford was seized, he had stopped working as a financial consultant six months prior. “Thank God it made me step away from Juan Orlando Hernández’s presidential campaign, because he won the primary soon afterward and then went to the general election, and then there was a real uproar,” said Figueroa. “But I was already gone by then, far away from the party. God led me away from all that.”

Former President Hernández is currently in preventive detention in the installations of the special forces police in Tegucigalpa, awaiting the Honduran supreme court’s decision about whether to allow his extradition. After the brazen corruption surrounding Hernández, the National Party lost significant sway in the November 2021 elections, and is currently trying to recuperate its strength in congress.

Meanwhile, Xiomara Castro, of the Liberty and Refoundation Party (Libertad y Refundación – Libre), has taken the reins of the executive. Her campaign was able to dispense with the National Party’s long grip on power by forming a coalition between a center-right and a left-wing party.

And on February 22, 2022, the new foreign minister, Eduardo Enrique Reina, ordered all acting diplomats, ambassadors, and consuls to resign from their positions within three days.

*The following reporters and organizations collaborated in this report: Alberto Pradilla from Animal Político (Mexico); Alicia Ortega and Yanina Estévez from El Informe con Alicia Ortega-Noticias SIN (the Dominican Republic); and the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project ID Research Desk. Part of this investigation was funded by the International Women’s Media Foundation. Rigoberto Carvajal, Diego Arce and the data team at CLIP contributed to the creation of the graphics and timeline. Andrés Bermúdez Liévano of CLIP contributed to the editing.