An environmental conflict marked by violence is raging in Guapinol, Honduras, where local inhabitants are resisting an iron oxide mine in a national park. This cross-border journalism alliance* has uncovered that Nucor Corporation, the chief steel producer in the United States, was a powerful hidden partner behind the mining project.

By: Jennifer Ávila and Danielle Mackey

Gerardo Reyes, head of Univision Investiga, and Maria Teresa Ronderos, director of Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística (CLIP), contributed to this article.

Ilustrated by Miguel Méndez.

Discreetly and without public announcement, the largest steel producer in the United States, the Nucor Corporation, spent at least four years associated with an iron mine in Honduras that is under fire for its alleged persecution of social leaders. They are protesting the ecological damage the mine may cause to protected land, according to documents obtained through a cross-border journalism collaboration between Contracorriente, the Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística (CLIP) and the Univision Investigative Unit.

Nucor, a publicly traded company coddled by President Donald Trump, partnered in 2015 with the prominent Honduran businessman Lenir Pérez and his wife Ana Isabel Facussé. They own Inversiones Los Pinares — a company that is battling residents of a town called Guapinol, who oppose the company’s planned mine in the Carlos Escaleras National Park, in the northern part of this Central American nation. The conflict has left a trail of dead, injured and imprisoned people.

According to public records in Panama, Nucor executives joined the board of directors of the Panamanian company NE Holdings Subsidiary in March 2015, and later joined a second Panamanian company, NE Holdings, in August 2016. The Pérez-Facussé couple had granted the total shares of three of their Honduran companies to the Panamanian firms in 2015, according to Honduran public records. One of these companies was Inversiones Los Pinares (previously Emco Mining), the holder of the controversial mining concession.

Inversiones Los Pinares has not yet begun mining the 200-hectare concession, located in a national forest reserve, that it received from the Honduran government. But in 2018, the company began building an access road to the planned mine site, which it will use to transport iron oxide to a pelletizing plant in the nearby city of Tocoa. The plant, which will melt the iron with carbon or coke to form compound pellets — part of the steelmaking process — is 99.6% owned by Inversiones Ecotek S.A. de C.V., a company created in 2017 in Honduras by Pérez and Facussé. The plant’s remaining 0.4% of shares belong to another mining firm owned by Pérez and engulfed in conflict, Empresa Minera La Victoria, S.A.

According to the Panamanian registry, the partnership between the Honduran and U.S. companies included an agreement by which a subsidiary of Nucor incorporated in Switzerland, Nucor Trading, would purchase the raw materials produced by the mine.

The partnership was created in remarkable secrecy. In response to written questions from this journalistic alliance, Nucor did not explain why it signed a backdoor agreement and did not register its investment in Honduras. Katherine Miller, director of public affairs and corporate communications at Nucor, responded by email, “As is common with joint business ventures sited in foreign locations, the participants chose a location to form the venture that is neutral and equitable to both parties,” referring to Panama.

Although the company has acknowledged multiple subsidiaries in past reports to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), it has never reported the two subsidiaries involved in this mining project, as far as this journalistic alliance could confirm. Nucor did not respond to repeated questioning about this issue.

“We are always seeking opportunities to secure an abundant supply of iron ore products to help make our steel,” wrote Miller. She stated that the company saw a “logistical advantage” in Honduras and “evaluated potential opportunities to strengthen our supply chain through an investment in a minority equity position in NE Holdings, Inc.”

The company left the project due to social unrest in the area, according to its spokeswoman. “As disruptions at the site [Guapinol] turned increasingly violent and safety concerns for personnel escalated, Nucor, in consultation with its Honduran counterparts, elected to exit its equity investment in NE Holdings in October 2019,” Miller wrote. “Nucor no longer holds an ownership interest, nor does it influence the direction of the company.”

A second Nucor subsidiary was involved in the project: Nucor South America, registered in the tax haven of Delaware. According to the Panamanian documents, Nucor South America reserved the power to leave the partnership by selling its shares in NE Holdings to a company named Aluminios y Techos de Guatemala (Alutech).

Upon consulting the Guatemalan public registry for Alutech documents, this journalistic alliance found yet another company owned by Pérez and Facussé, broadly constituted but specialized in distributing construction materials. The company did not report a stock purchase in 2019. The only significant change it declared was in October 2018, when its capital jumped from 5,000 Guatemalan quetzales to 60 million quetzales — from about $650.00 USD to about $7.6 million.

Neither Nucor nor Pérez, who Univision interviewed in Miami, were willing to give further details, like the total investment amount or the plan to meet environmental and social protection standards. Pérez insisted that a confidentiality agreement with the U.S. company prevented him from speaking further.

Pérez said in a Whatsapp message prior to the interview, “Nucor is not with us; it intended to begin the project but with this whole problem it pulled out. They are a serious company and it was impossible to finalize the transaction due to this problem.”

In its response, Nucor said it sold its shares in NE Holdings in October 2019. But this assertion is unclear, because Panamanian documents show that two months prior, in August, Nucor’s officials left the company’s board of directors. The U.S. firm also declined to explain why on that same date in August, two Nucor executives joined the board of directors of NE Holdings Subsidiary. Those executives were Christopher Adam Goebel, who appears on LinkedIn as an operations manager, and John Lowry Pressly, who is listed in a company report as a general manager for Latin America. Pressly did not respond to emails Univision sent to the Nucor corporate account, but he transferred the interview request to the company spokeswoman. These Nucor officials also sit on the board of Ecotek, the pelletizing plant planned for construction in Tocoa.

When questioned about these links, Nucor’s representative neither confirmed nor denied Goebel and Pressly’s roles. She only said that the documents would be updated in the near future to reflect the fact that the company no longer had connections to the project.

This is not Nucor’s first foray into the iron and steel sector in Honduras. The company paid 12 million dollars for shares in Aceros Alfa, the largest steel company in the country, according to the public profile of a lawyer who facilitated the deal, Grossnie Velásquez of Consortium Legal. In response to queries about the date of this investment, Velásquez declined to answer, citing confidentiality. Nor did Nucor reference this investment when asked about its presence in Honduras.

Nucor’s main business partner in Aceros Alfa is Juan Antonio Kattan, from the well-known wealthy family that founded Alfa and also does business in the banking and oil sectors. Nucor conducted its investment via another subsidiary incorporated in Delaware — Nucor Harry U.S. Holdings, which it reported to the SEC — and it holds the second-largest share of stock in Aceros Alfa after American Holdings LTD, according to Honduran public documents.

Another partner in Aceros Alfa, Jacobo Atala Zablah, is a member of the family that owns the Agua Zarca hydroelectric project, which emblematic Honduran environmentalist Berta Cáceres protested until her murder in 2016. There is no existing legal proceeding that implicates this firm, nor its associates, in her assassination.

The Legal Dealings

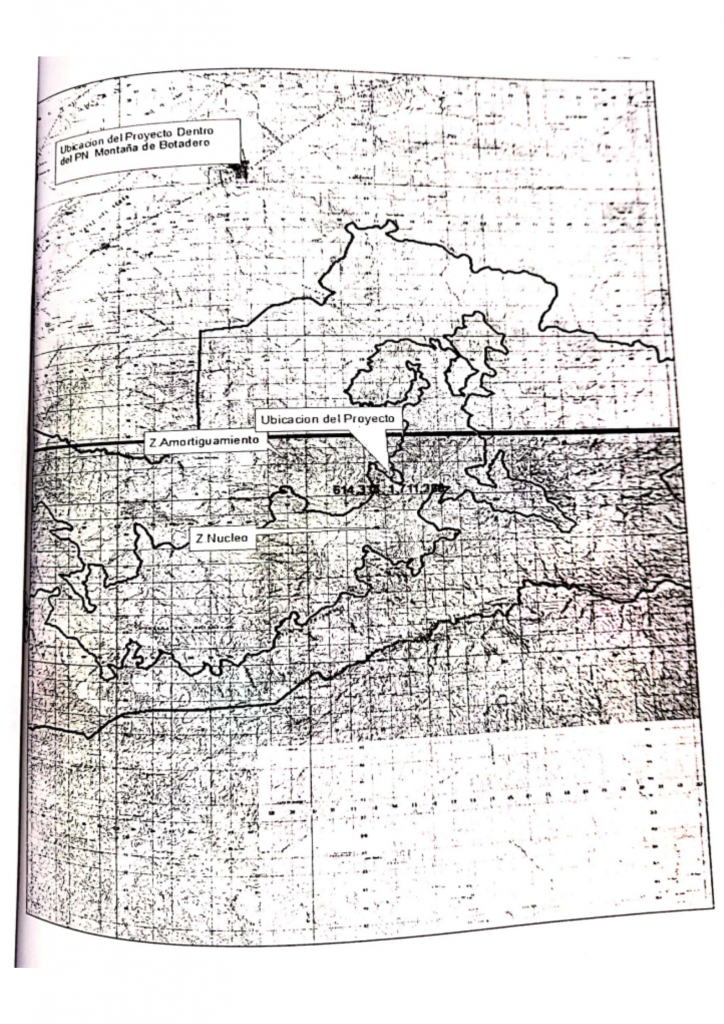

The Los Pinares mine sits in an area that, until December 2013, fell within the central nucleus of the Montaña de Botaderos Carlos Escaleras Mejía National Park. The park houses the mouths of 34 rivers, crucial for hydrating the region. It was named in honor of an environmentalist killed in 1997 when he opposed the African palm oil processing plant run by Dinant, a company owned by the late Miguel Facussé, father-in-law of Lenir Pérez and father of Ana Isabel Facussé.

Less than two decades later, how was it possible for these companies to undertake a mining project in this nature reserve that is protected by law?

On October 8, 2012, the Honduran government ordered the conservation of 96,724.40 hectares of an ecosystem, meant to protect its present and future flora and fauna and historical, cultural, and anthropological resources. In April 2013, Emco Mining (now Inversiones Los Pinares) requested two concessions for non-metallic mining exploration for iron oxide in an area that was, at that time, still part of the reserve’s nucleus, according to the Honduran National Institute of Geology and Mines (INGEOMIN).

Eight months later, in December 2013, the Honduran congress issued Legislative Decree 252-2013, modifying the park’s boundaries to remove 217 hectares from the nucleus. Now the mine’s location was no longer in the nucleus but instead in the “buffer” zone, in which Honduran law allows non-metallic mining. (Iron oxide extraction is classified as non-metallic in Honduras.) The modification was questioned by the Honduran government’s Institute for Forest Conservation, Protected Areas, and Wildlife (ICF by its Spanish abbreviation), which designates and manages natural reserves.

In 2014, the ICF deemed the iron oxide mine “unviable”, finding it would cause severe impacts on the park’ s flora and fauna. The project is an open-pit mine and, even with the legislative reform, the concession is located very close to the park’s new nucleus. The report also determined the mine could harm 32 hectares of broadleaf forest and a river just 100 meters away that hydrates a community called Corozales. But according to a source from the ICF, the congress never consulted the institute before reducing the park’s nucleus.

Despite the ICF’s report, another public agency, the Secretariat for Natural Resources, granted the project an environmental license. The minister of the secretariat when Los Pinares received its environmental license, José Galdámez, has been questioned for green-lighting another project in a protected area of Tegucigalpa, the capital of the country. Galdámez eventually left his position.

Pérez told Univision that his company sponsored meetings around the region with public officials, in which they could hear concerns from local inhabitants to “reconsider” the boundaries of the national park.

“The park had been declared a national park 12 months earlier and we brought all the actors together and asked them to reconsider,” said Pérez in an email. “We play fair,” the businessman added.

With a signed environmental permit and a legal reform that was a match made in heaven for the mining companies, it was only a matter of months before Inversiones Los Pinares received the rights to concessions “ASP” and “ASP2,” 100 hectares each, to dig for iron oxide. Additionally, Minera La Victoria, a company that is also a partner in the Panamanian holdings, received two concessions of 1,000 hectares each, in the neighboring department of Atlántida, to extract iron oxide.

According to article 56 of the 2013 Honduran mining law, for this type of mining concession, companies must pay the equivalent of US$0.50 per hectare per year for exploration rights, and US$2.00 per hectare per year to exploit the minerals. This means that since exploration began in 2013, the concession has cost Inversiones Los Pinares 100 dollars per year, and it will pay 400 dollars per year once mining begins. The mining canon for La Victoria, around 500 dollars per year, is more due to the larger size of its concession, which is valid through 2023. Additionally, the companies will have to pay royalties on the production of iron oxide to the municipality and mining authorities, along with a security fee totaling 2.5% of the value of the materials that are either exported (FOB) or in the plant.

Iron and Resistance

In addition to the rapid reduction of the park’s protected area, thereby allowing mining, socio-environmental conflicts are raging behind the scenes of these concessions. In 2016, when Minera La Victoria began exploration for its project in Atlántida, the surrounding communities protested the harm that they feared the mine would cause; the company has stopped project development at this time.

That same year, the conflict spread to Tocoa, in the department of Colon. When the inhabitants of the town of Guapinol discovered a company planning to mine in their area had obtained one of the 39 mining licenses the government had granted between 2015 to 2020, according to the INGEOMIN database, they took to the streets in protest. (Only eight of these licenses are currently active, while the remaining 31 have expired.) The people of Guapinol feared the mines would harm the rivers that supply the town with water, and they cited serious irregularities in the concession authorization processes.

The inhabitants created the Municipal Committee for the Defense of Public and Common Goods and submitted five requests, starting in 2017, for public consultations for community members to be able to decide whether or not they wanted a mine in their area. Local organizers gathered signatures, held demonstrations in front of the city hall, and blocked access roads. Despite their efforts, the calls for consultation fell on deaf ears.

In 2018, Inversiones Los Pinares began building an access road to its concession in the Montaña de Botaderos site, and the community reported that the waters of the Guapinol River became muddied and unusable. In August of that year, the community established an encampment that blocked the construction of the access road for two months.

Juana Esquivel, the Director of the San Alonso Rodríguez Foundation in Tocoa, said the protest was held because “nature is life.” She continued: “Here on this land is where our ancestors lived. We are defending their legacy, and our right not to be displaced, not to be forced to migrate to other countries, our right to stay and live in harmony with Mother Earth,” she said, “just as we had done until these companies came and generated widespread terror with their threats, abuse, and destruction of life itself.”

The mining company’s owner, Lenir Pérez, sees things differently. In an interview with Univision, Pérez said the construction of the access road brought progress to the area, where he said he had also built four schools and 147 latrines. His company, he added, was employing 1,000 people, and for these reasons, he claimed the majority of the inhabitants of La Ceibita, the town where he plans to build the pelletizing plant, widely support the project. He claimed the people of Guapinol also support the project, and he sent this journalistic alliance signatures and testimonies of people who attended “project socialization meetings” near the end of November 2017. Socialization is a process by which communities can express their opinions about the advantages or disadvantages of a mining project.

According to data collected by Inversiones Ecotek, 79% of local communities are “in agreement and see it in a favorable light, while 7% are in disagreement and 14% are indifferent to the presence of the project in this area.”

Pérez says he is persecuted by leftist organizations that bring outsiders to the area “and ask the women to cry” to create negative publicity. “We are victims of a storyline that’s not real,” he said.

Nucor, the U.S. company, added, “Despite exiting, Nucor believes the project will provide an opportunity for meaningful long-term and high-quality jobs for the local Honduran population on socially and environmentally responsible terms.”

Disturbances and Accusations

On September 7, 2018, attempts by mine personnel to clear the demonstrators from their road blockade led to a first clash. A number of local inhabitants suffered physical injuries, including one person by gunfire. The case’s legal file describes protesters detaining Santos Corea, head of security for the mine, for three to five hours as they burned a dumpster and destroyed a vehicle. Later, on October 27, police officers and military personnel forcefully expelled the protest camp from the road worksite. The confrontation between the community and state forces continued in the following days, and two soldiers were killed by crossfire on October 29. There has been no formal legal investigation into those deaths, but the mining company did file a suit against the protesters, and 32 of them face diverse charges stemming from the September 7th conflict. The defendants include four delegates from the Catholic parish in Tocoa and an employee from the San Alonso Foundation.

In 2019, twelve of the accused environmentalists appeared voluntarily before authorities to confront the charges against them: usurpation, unlawful detention, illicit association, robbery, aggravated robbery and arson. The prosecution based its accusations on a police intelligence report that claimed 51 individuals participated in crimes against the company and were supported by at least another 300 people. The prosecutor said the police had designated the group as organized crime, dubbing it “The Anti-Miners” and alleging it orchestrated the actions in question.

The leaders of the Municipal Committee for the Defense of Common and Public Goods are the activists most exposed to risk in the community struggle against the mine. They cite contradictions in the claims made by the company and the prosecutor. For example, one of the accused, Juan López, was not at the September 7th clash; he was at the San Alonso Rodríguez Foundation headquarters where he worked, drafting a statement. Another defendant, Antonio Martínez Ramos, died in 2015 – three years before the events occurred.

"We can clearly see the charges against people who weren't at the scene, another person who had died before the conflict, others who never participated in this citizen protest," said Esquivel of the San Alonso Rodríguez Foundation, who is also a member of the municipal committee.

“There has not been any response whatsoever to the dozens of citizen allegations of possible corruption in the approval process for these concessions.”

Lenir Pérez said that the Honduran public prosecutor is the party responsible for correctly identifying the accused and their acts.

There are still eight people in prison awaiting trial, while another five have been released (including Juan López), although they still face charges. The prosecution dropped the charges against seven, and another nine are still at large. Two of the defendants have been killed: Roberto Argueta Tejada in August 2019, and Arnold Morazán Erazo in October 2020.

In an interview conducted for this story, Lenir Pérez offered assurances that his company had not taken any violent action, saying, “I’ll put my name on the line, I’m telling the truth.” Pérez argued that Morazán Erazo was killed after he had begun to work on the community support projects that the company launched in Guapinol, and was organizing a plan to remove the current community leaders. Perez said that nine of his own employees and collaborators had been killed.

Pérez said the worst security threats have been against those who defend the mining project, and he said those threats were orchestrated by Jesuit priests, the San Alonso Foundation and all of their allies.

"I'll close the mine and carry on with my businesses," said Pérez, "but they'll lose the opportunity to develop themselves -- and not just one of them, but all of them." That's why Nucor left and Honduras lost an opportunity for significant investment, he claimed.

“Pattern of violence”

After having studied the legal aspects of the conflict, the International Human Rights Law Clinic of the University of Virginia School of Law published a report that argued for the liberation of the incarcerated environmentalists.

“This case [by the government against the protesters] falls in line with a pattern of violence, harassment, and intimidation directed towards human rights defenders in Honduras,” states the August 31, 2020 report. The text continues that this criminalization of social leaders “illustrates the government’s tendency to favor economic interests over human rights and its willingness to attack their citizens’ freedom of association, expression, and peaceful assembly.”

The academics concluded that the actions of the Honduran government included “potentially unlawful” moves, because, they explained, those moves could violate international civil rights legislation that guarantees the right to appeal detention.

The Clinic also raised questions about the government’s use of laws designed to take down organized crime laws as a tool to stop legitimate social protest.

Pérez — who has attracted attention in Honduras in recent months for having won the construction contract for the country’s new international airport on the U.S. military base at Palmerola — said he only wanted the people responsible for breaking in and burning the company property to be tried in court, just as anyone would reasonably want if their house was attacked.

“If I go burn down your house, kidnap your family, that is a crime,” Pérez said.

Ana Isabel Facussé, Pérez’s wife and partner in all of his business ventures, is the daughter of the deceased Miguel Facussé, a wealthy and prominent owner of African palm plantations who was described in a Los Angeles Times obituary as a “ruthless Honduran tycoon.”

The activists who oppose mining in the national park also cite studies conducted by Honduran authorities about the harm that mining could cause in the protected area. The ICF’s Management Plan underscores the biological wealth of the park and how these resources have already been damaged by mining exploration activities, widespread agriculture, and the presence of criminal groups that have used the park area to raise livestock and grow illegal crops.

“Mining activity is not so bad per se, but it can be harmful especially in vulnerable areas such as a protected zone with a highly fragile nucleus, even at low intensity,” explained an expert from the ICF Wildlife Department, the same agency that declared in 2014 that the mining project on protected land was unviable. “What the congress took on — [a decision] about shrinking the park or its nucleus area — wasn’t the most prudent, because we’re diminishing conservation areas.”

Defending the environment in Honduras is a dangerous task. The country has recorded at least 685 violent acts against environmental and land rights defenders since 2009, a figure only surpassed in the region by Brazil, and by far the highest rate when adjusted for the number of inhabitants, as reported this year in the Tierra de Resistentes journalism project in which Contracorriente and CLIP participated.

In 2019, the Municipal Committee for the Defense of Common and Public Goods was awarded the prestigious Letelier-Moffit Human Rights Award in Washington, DC. In 2020, the Committee was also a finalist for the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought, given by the European Parliament to past winners including Nelson Mandela and Malala Yousafzai, among other notable pacifists.

In an open letter by 30 European Parliamentarians protesting the pretrial detention of Guapinol social leaders, they wrote: “We are especially concerned[D1] by the prolonged detention and judicial harassment against the defenders, despite the lack of clear incriminatory evidence (of the crimes of which they’re accused).” High-ranking officials from the OAS and the United Nations echoed this same concern.

“I believe it’s essential that people question why there are eight people still in prison for defending a right as fundamental as water,” said Spanish delegate to the European Parliament and member of the Human Rights Subcommittee, Miguel Urbán Crespo, to this journalistic alliance.

In response to the international voices of concern, Lenir Pérez alleges the existence of an elaborate structure with potent capacity to hoodwink international actors into believing a fabricated “movie.”

“In this structure, everyone needs a story, and with that story they build up their profile in an NGO, they come to the United States to give conferences, they receive prizes in Europe, they’re happy to be imprisoned because what’s in their interest is the drama,” said Pérez, who furthermore said he had tried to establish communication with community leaders but has been rebuffed.

When consulted on this question, three community leaders said they have not received any formal proposal for negotiation from the company. One of the leaders, whose name we are not revealing for her safety, said she had only received a visit from a man who doesn’t work for the company but was sent by Lenir Pérez and “basically showed up to intimidate me.” Others said that the Secretary of the Environment[D2] tried to bring them together to negotiate with the company, “to take advantage [of the opportunity[D3] ].” They didn’t accept the offer “because negotiations should belong to the victimized communities.”

Nucor and Trump

In 2014, John Ferriola, then CEO of Nucor, told Time Magazine that Honduras could play a central role in Nucor’s strategy to revive the U.S. steel industry. Nucor would produce pellets that, when combined with recycled steel, would improve product quality and reduce costs. The company could then begin to expand its pelletizing operations to places like Latin America. “When you look at that whole area, you say, ‘Boy, if somebody had a place here, there, there and there, we would capture the market,’” said Ferriola.

Despite these announcements, when Nucor invested in iron mining and steel production in Honduras, it did not do so by the light of day. Instead, its subsidiaries -- Nucor South America and Nucor Trading -- partnered with holding firms for Hondurans created in a tax haven, Panama.

Nucor emphasized that its investment in NE Holdings was consistent with its commitment to “conducting business in a manner consistent with high standards of environmental and social responsibility.” Additionally, the spokeswoman said they ask their supplieres and business partners to uphold these standards, as enshrined in various internal codes and policies.

Nucor was an important donor to Donald Trump’s presidential campaign in 2016 and 2020. For instance, for the 2020 election, which the president just lost, a Political Action Committee associated with the company donated the maximum amount of $10,000 to the then-Republican candidate, as Quartz revealed. Under the Trump administration, reforms aimed at benefiting from the steel sector particularly favored Nucor, according to an investigation by the New York Times. One of the most significant involved tariff considerations that favored Nucor to the detriment of other U.S. companies, creating tensions within the industry.

Nucor also contributed one million dollars toward the production of a documentary called “Death by China”, by Peter Navarro, an economist who served as Trump’s main trade advisor, according to the New York Times. The documentary argues that China, a large steel producer, poses a threat to U.S. economic power.

In August 2017, after Trump refused to condemn the white supremacists involved in a Charlottesville protest that left one woman dead and several people wounded, 11 of the 28 senior executives who sat on the American Manufacturing Council resigned in protest. Nucor is a council member, but its representative did not resign, nor speak out against the president’s racism.

“Nucor has benefited from a cozy relationship with the Trump’s White House,” said Leonardo Valenzuela Pérez, a researcher for the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee (UUSC) in Boston. “This administration has favored protectionist measures that directly benefit Nucor and denounced trade competitors like China. Meanwhile it seems that Nucor is hypocritically hiding their businesses abroad, disrupting rural communities and their environment.”

The situation is particularly ironic given the Trump administration’s obsession with stopping immigration from Central America. “The brutal imposition of mining and energy infrastructure projects in Honduras during the last decade has followed a logic of silencing dissent, leading to murders and expulsion, forcing large numbers of people to migrate to the United States,” Valenzuela said.

Hank Johnson, a Democratic congressman from Georgia who has closely followed Honduras, told this journalistic alliance that rural indigenous communities and the poor of Central America frequently suffer from business practices that cause environmental harm and repress social protest. “They’re driven from their land by these companies and forced to make that pilgrimage to America,” the Congressman said, “and they’re fed into a private for-profit detention system.”

Over the course of 2018, the pellitizing plant obtained only a conditional environmental license, because authorities found that the socialization of the project with communities that will be directly impacted was incomplete and did not meet standards, according to Ecotek’s environmental licensure file. The population of Tocoa, the largest city near Guapinol, along with other groups of neighbors with a stake in the conflict, asked the mayor to declare the municipality a mining-free zone. The mayoral administration passed that resolution. Nevertheless, construction has not stopped. Pérez said that in 12 months, they plan to begin mining.

In September 2020, aides representing the members of the House Foreign Affairs Committee held an off-the-record meeting with three Honduran human rights defenders, including Juan López of the Municipal Committee for the Defense of Common and Public Goods, in which the aides learned about the situation in Guapinol. López is one of the people charged with crimes after protesting the mine, and he is among the group that, in 2019, voluntarily presented themselves before authorities to face the charges.

Congressman Johnson stated that it is important to understand the involvement of a giant U.S. corporation in such problematic business in Honduras within the context of a close relationship between President Trump and the polemical administration of President Juan Orlando Hernández. The congressman explained that President Hernández is under investigation in the United States following the 2019 federal conviction of his brother for drug trafficking.

“This points to the moral depravity of the Trump administration," the congressman said, which "has forged a close partnership with this corrupt narco-state,” he said. “The corruption is on both sides.”

Currently, Honduras has no U.S. Ambassador — but Ambassador James Nealon, who was serving in that post when Nucor invested in the project, told Univision that he had no knowledge of the deal, nor of any visits by the steel giant’s executives to the country.

When, in 2019, Juan López accepted the Letelier-Moffitt award in Washington on behalf of his colleagues, he repeated the words spoken by environmentalist Berta Cáceres in her own acceptance speech at the 2015 the Goldman Environmental Prize, months before she was gunned down: “Wake up, humanity, we are out of time!”