The first 100 days of Honduran president Xiomara Castro’s administration have exposed the complex situation facing Honduras. Internal conflicts within the president’s party and the political alliance that won the elections last November have hampered real change. Although Castro has kept some of her promises, the country’s structural problems are holding her back in many ways. Un met campaign commitments loom over the first female president of Honduras, including her promises made to women.

By Vienna Herrera

Photos by Jorge Cabrera and Fernando Destephen

In her inaugural speech, Honduras’ first female president enumerated 21 urgent tasks for her first 100 days in office. That milestone has come and gone, and President Xiomara Castro’s performance reveals lackluster results: five of the 21 tasks were completed, seven were partially completed, and seven were not addressed.

Our analysis excluded two irrelevant promises made in the inaugural speech: to imbue the Armed Forces with the power to protect the environment, which it already had, and to grant amnesty to the Guapinol prisoners, who were freed without needing the promised amnesty. Two unfulfilled commitments pertain to demands for female sexual and reproductive rights, and food sovereignty tied to lower bank interest rates for food producers and environmental protection.

Lester Ramírez, director of transparency and governance for the Association for a More Just Society (ASJ) sees a lot of improvisation in the new administration – normal during a transition period – and expects more formality as the year goes on. The government’s greatest challenge, says Ramírez, will be to deliver its number one campaign promise; national reconciliation.

“The president talked about this right after she won the election, and reconciliation still hasn’t happened. We are living in highly polarized times, and the young men and women who swept this administration into power are feeling very disappointed and betrayed because they are not getting what they expected,” said Ramírez.

Ricardo Castañeda, an economist with the Central American Institute for Fiscal Research (Instituto Centroamericano de Estudios Fiscales – ICEFI), said, “These first 100 days have revealed the government’s priorities and its appetite for addressing other issues.”

Despite the propensity for new governments to establish 100-day goals, Castañeda feels that it is important for them to set realistic expectations because complex problems are not solved overnight.

“This government should leverage the high levels of legitimacy and political capital that it currently enjoys because we have seen in other countries how quickly this political capital and legitimacy can erode. It’s important to have technical studies and inclusive dialogue as a foundation for any major reforms,” he said.

Promises fulfilled during Castro’s first 100 days

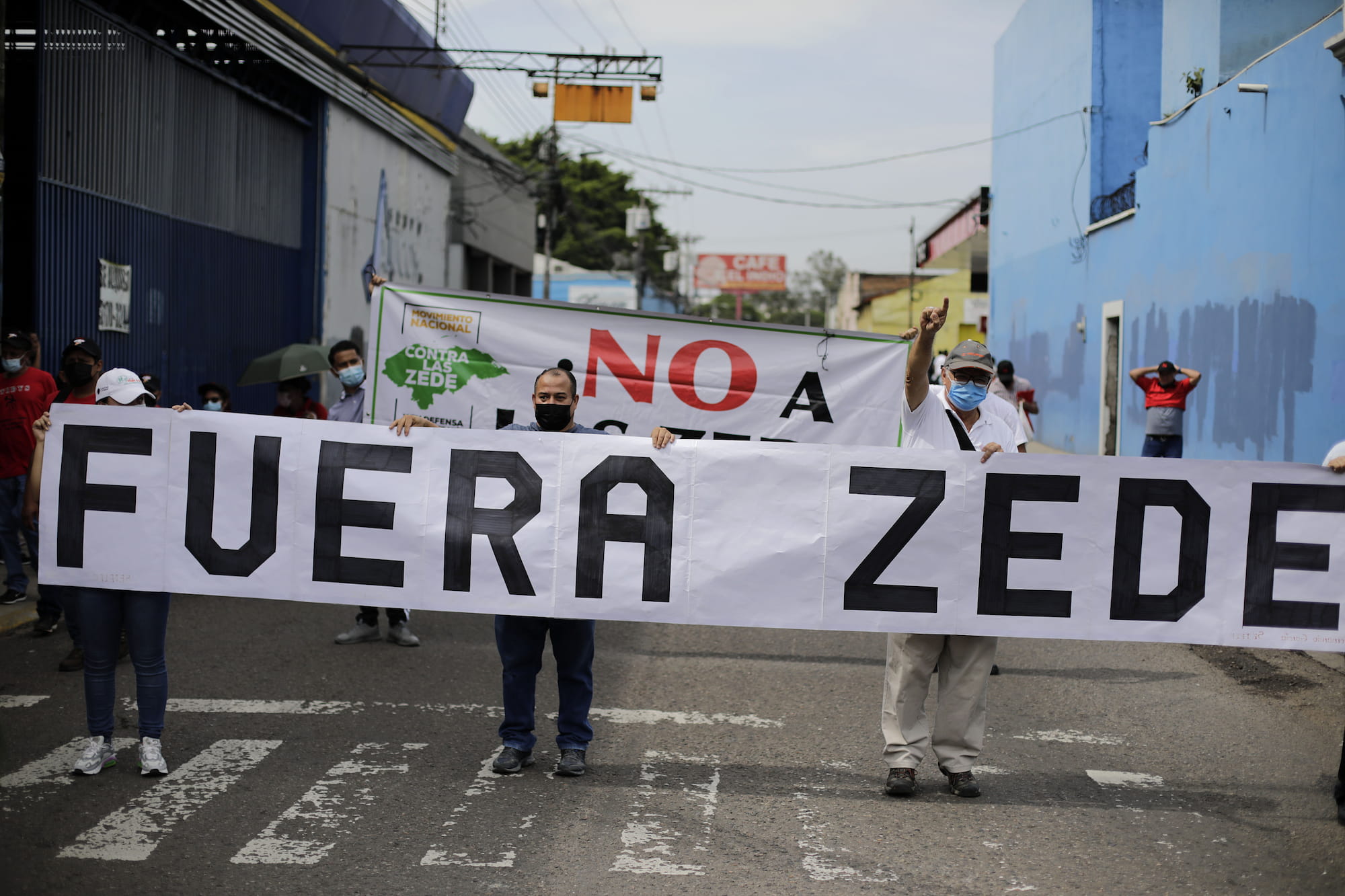

- Repealed laws authorizing the Employment and Economic Development Zones (ZEDEs)

- Implemented fuel subsidies

- Restored Honduran nationality for Father Andres Tamayo

- Implemented an electricity subsidy for households that consume less than 150 KW/H/month

- Amended the government budget approved by the previous administration

100 days and still no emergency contraception or concrete measures for women

“The president has said that this is the century of woman, but when is it going to start? We have no clear direction or support from our president,” said Jinna Rosales, a member of a group advocating for government authorization of the emergency contraceptive pill (ECP) (Grupo Estratégico por la Pastilla Anticonceptiva de Emergencia – GE-PAE).

Rosales said she is tired of reminding people of how important it is to repeal the 2009 ban on emergency contraception, “We have been meeting on other topics, but no one wants to talk about the ECP ─ there’s some sort of fear.” She said that feminist organizations left their March 8 meeting at the Presidential House with high hopes, but now have doubts about whether the government will be able to deliver.

Ana Ruth García is a pastor and coordinator of the Ecumenical Advocates for the Right to Choose (Ecumenicas por el Derecho a Decidir). After the March 8 meeting, the president appointed Health Minister José Matheu (Salvation Party of Honduras) to communicate with women’s groups.

“We met at his home because he didn’t want to attract media attention by meeting in his office,” said Garcia. “He raised the same old unscientific arguments that emergency contraception has only been approved for rats and monkeys and not for human beings, which we refuted.”

Several sources who attended the meeting with Mathei told Contracorriente reporters that Human Rights Minister Natalie Roque was also present. According to these sources, Roque, who is known within the Libre Party for her feminism, supported Matheu’s opinion about how “harmful the pill is” and told the meeting participants that it wasn’t the right time for the president to take up this issue.

Roque confirmed having attended the meeting as a mediator but told Contracorriente that she was not against it [the ECP] because “the right to emergency contraception is part of female sexual and reproductive health rights for which we have a responsibility as a government [to protect].” She claims to have urged the Health Minister to remove all restrictions on the use of the ECP.

“Several issues were raised in that meeting,” said Roque. “One was the valid concern that some young women in urban areas use the ECP as a routine contraceptive method, which has serious health consequences.” Roque made this assertion despite studies by the World Health Organization indicating that repeated use of the ECP poses no known health risks, but that more effective methods of contraception are better.

Roque backpedaled on her recent statements to The New York Times that the government “is not in a position to start a fight with an enemy as powerful as the Church,” and that legalizing the ECP now would simply be “adding fuel to the fire.”

She told Contracorriente that this was not her own view, but rather an opinion the Health Minister expressed to her. “I would never say that women, especially victims of violence, should wait even longer. What I told them [The New York Times] is that the government is being challenged on all sides right now, and the feminist agenda and women’s sexual and reproductive health issues are being used to attack the government.”

In June 2021, when she was running for president, Xiomara Castro met with feminist organizations and signed an agreement to address some of their demands. The agreement includes a commitment to enable women to fully exercise their right to sexual and reproductive health “free of religious fundamentalism. [I] commit to doing this early in my presidency, to repeal the ECP ban, and to approve the protocol for caring for survivors of sexual violence.”

Jinna Rosales believes that the ECP ban is still in place because of all the men close to the president. “These macho men in government positions are constantly chirping in the president’s ear, ‘No, don’t do it.’ What’s the problem? It’s all these high-level government officials, ministers, and directors who are saying that women’s issues are not a priority,” she said.

Jessica Sánchez, an analyst of feminist issues, says that Castro owes Honduran women a great deal. “She positioned her campaign to speak to the feminist movement, she repeated its slogans and identified with its struggles. But now it seems that she’s obligated to a lot of people who don’t know what to do. She has been co-opted and can’t say ‘No’ without everyone declaring that government infighting is endangering her ability to govern,” said Sánchez.

President Castro also promised to reduce femicides and violence against women, but this type of violence persists, while the female victims are ignored. On February 3, 2022, Rosaura, for example, survived an attack by a man who repeatedly harassed her in Choluteca (southern Honduras). Three months later, her assailant has not been brought to justice and is still at large.

Read (in Spanish):The consequences for Rosaura, a survivor of attempted murder

The femicide rate in Honduras continues unabated. Ecumenical Advocates for the Right to Choose has recorded 100 femicides in Honduras so far in 2022 (January-April), equaling the number for the same period in 2021.

Jinna Rosales is clearly frustrated by these numbers. “This data is alarming ─ it demonstrates that women are living in crisis. When three policemen were murdered, the government acted immediately and declared a state of siege in Colón. The very next day, four women were killed in Yoro but the government did nothing,” she said.

Unfulfilled promises during Castro’s first 100 days

- Focus on agricultural development and food sovereignty; renegotiate CAFTA

- Ensure government transparency and develop a digital, pro-development republic

- Justice for Berta Cáceres

- Create mechanisms to lower bank interest rates for agricultural producers

- Senior citizens, people with disabilities, children, youth, indigenous peoples and afro-descendants, and the LGTBI community to have a place and voice in her government

- Repeal laws that undermine social protections and criminalize poverty, and that foster corruption and looting of public wealth and financial trusts.

- Hold a referendum on constitutional reforms

The change in government brought about a restructuring of the National Police that elevated women to 40% of the country’s police chief positions. However, the Security Ministry has not presented a plan to reduce femicide rates.

“We have been unable to eradicate years and years of macho and patriarchal thinking and practices despite high levels of violence against women. Yet the priorities of the Security Ministry seem to lie elsewhere,” said Gilda Rivera, coordinator for the Center for Women’s Rights (Centro de Derechos de Mujeres – CDM).

The government has moved forward on some gender issues. On March 8, Castro sent a bill to the National Congress to elevate the National Women’s Institute (Instituto Nacional de la Mujer – INAM) to ministerial level, as well as a bill to enact the Comprehensive Law against Gender Violence; an initiative sponsored by various civil society organizations.

Rivera said that she feels more openness on the part of the president’s office and the National Women’s Institute. She and the gender commission established by the National Congress met with representatives of the president to discuss the proposed laws.

“Some of the comments made in the meeting indicate that the process might be slower than expected, especially because of the intent to create a technical committee to monitor progress,” said Rivera.

Another open issue is the Law for Women’s Shelters, a proposed bill with a very different objective from the Comprehensive Law against Gender Violence. The Law for Women’s Shelters seeks US$410,000 in government funding for the country’s ten women’s shelters so that they don’t have to depend on international funding.

Jinna Rosales says that women’s organizations are losing patience. “We aren’t going to let ourselves be used anymore. [The government] tells international funding agencies that it’s in constant dialogue with us, but really all it’s doing is stalling for time and no progress is made.”

Internal crises expose pervasive machismo in government

Some recent government crises seem to have been resolved without the president’s involvement. The conflict in the National Congress in which two separate boards of directors competed for control was apparently resolved in a meeting between legislator Jorge Calix and Libre Party leader and former President Manuel Zelaya held in the Presidential House. This unusual turn of events revealed that even though the country elected its first female president, men are still active behind the scenes during crises, negotiations, and political violence.

Read (in Spanish):Back-room deals made by men expose ongoing exclusion of women and political violence

Similarly, legislator Mauricio Rivera (Libre Party) recently led an attack on the Women’s City to denounce its director and presidential appointee, Tatiana Lara. Although feminist activists from the Libre Party and other government officials publicly supported Lara, the president remained silent on the matter, even on Twitter. Yet on other occasions, the president has taken to Twitter to decry the use of leaked images from the Presidential House of former President Hernandez’s extradition, and to demand the immediate release of journalist Cesar Silva after he was arrested on defamation charges.

“We’re a little concerned about the president’s lack of visibility. When she does appear in public, she only talks about social and economic issues or about the approval of some proposed laws. But she’s silent on women’s rights,” said Jinna Rosales, who believes that the women’s movement in Honduras was weakened when many female activists took government jobs.

“I’m afraid this might have negative consequences for us in the long run, such as dissipating our objectives and struggles. We need strong responses. Women who become civil servants undoubtedly start off with the willingness and spirit to continue the struggle, but they are not the decision-makers,” said Rivera.

Jessica Sanchez said, “[The president] has to escape her own spiral of violence because it’s suffocating her. We haven’t seen this type of violence in politics before, and she has to escape that. She has to take charge of the country and of the efforts to empower women and reduce violence.”

The government owes people transparency

On March 1, the National Congress repealed the Law for the Classification of Public Documents Related to Security and Defense. While many people applauded the abolition of this law, it hasn’t had much effect on access to public information in Honduras.

On March 2, Finance Minister Rixi Moncada presented a report detailing how US$168 million was embezzled by the previous administration. The report indicated that 10 companies benefited the most from tax breaks and exemptions over the last 12 years. Contracorriente subsequently submitted an information request to the Ministry of Finance for the names of these companies. However, the ministry denied the request on the grounds that the Honduran tax code has provisions to protect public servants and other taxpayers “regarding the [tax] declarations and data provided by taxpayers or third parties, as well as information obtained in the exercise of the tax collection and audit function.”

Partially fulfilled promises during Castro’s first 100 days

- To implement an International Commission Against Impunity in Honduras (CICIH)

- To secure funding for in-person classes, face masks, vaccines, and school snacks

- To implement urgent measures promised during the presidential campaign to reestablish Honduras (as a socialist and democratic country)

- To repeal laws passed en masse on the last day of the previous National Congress

- To develop a foreign policy based on Central and Latin American sovereignty and solidarity

- To freeze all permits for river exploitation and open-pit mining; rescind illegal permits and concessions; preserve forest resources; and safeguard national parks and other protected areas.

- To repeal laws that undermine social protections and criminalize poverty, and that foster corruption and looting of public wealth and financial trusts.

The government’s transparency portal has not been updated since the new administration took power. Contracorriente recently submitted a request for information on Presidential House employees’ and the president’s appointed advisors’ pay. When one information request was denied and the other was answered erroneously, Contracorriente was compelled to submit an appeal to obtain the information.

Contracorriente’s experience with public information requests submitted during previous administrations is that the requests were often denied on the basis of internal rules, regulations, or codes. The Secrecy Law was rarely cited as the reason for the denial. Often, no response at all is received, requiring an appeal that can take months to resolve. Many people who submit information requests that go unanswered don’t bother to file an appeal.

ASJ’s Ramírez said that they asked a National Congress commission to conduct a detailed review of the Secrecy Law prior to abolition. “We told them that any measure to repeal the Secrecy Law had to ensure that the information protected in the past [by the Screcey Law] would be made available. I personally spoke to [legislators] Ramon Barrios, Fatima Mena, and Jari Dixon. These are the types of problems that arise when we don’t listen to the news media who are doing the investigative work, and we don’t give them the tools to do their jobs,” said Ramírez.

Commitments to protect the environment and help agricultural producers

One of President Castro’s 21 commitments for her first 100 days in office was to freeze approvals of permits and concessions for river exploitation, open-pit mining, and forest resource exploitation, and to preserve national parks and other protected areas. On March 1, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment declared that open-pit mining in Honduras was no more. But after much pressure from mining companies, the ministry backtracked on March 21 and said the elimination of open-pit mining would have to wait due to ongoing improvements to the ecosystems around the mines and to mitigate any negative impacts on neighboring communities [due to an abrupt cancellation].

Jessica Sánchez says that this fosters an environment of ungovernability. “They make these public statements, but they’re just statements and not binding like a presidential directive, nor are they submitted to the National Congress for ratification. This raises the issue of governance, especially with the board of directors of the National Congress. I feel insecure about these governance issues; she [the president] should declare, ‘I approve this’ and that’s it,” said Sánchez.

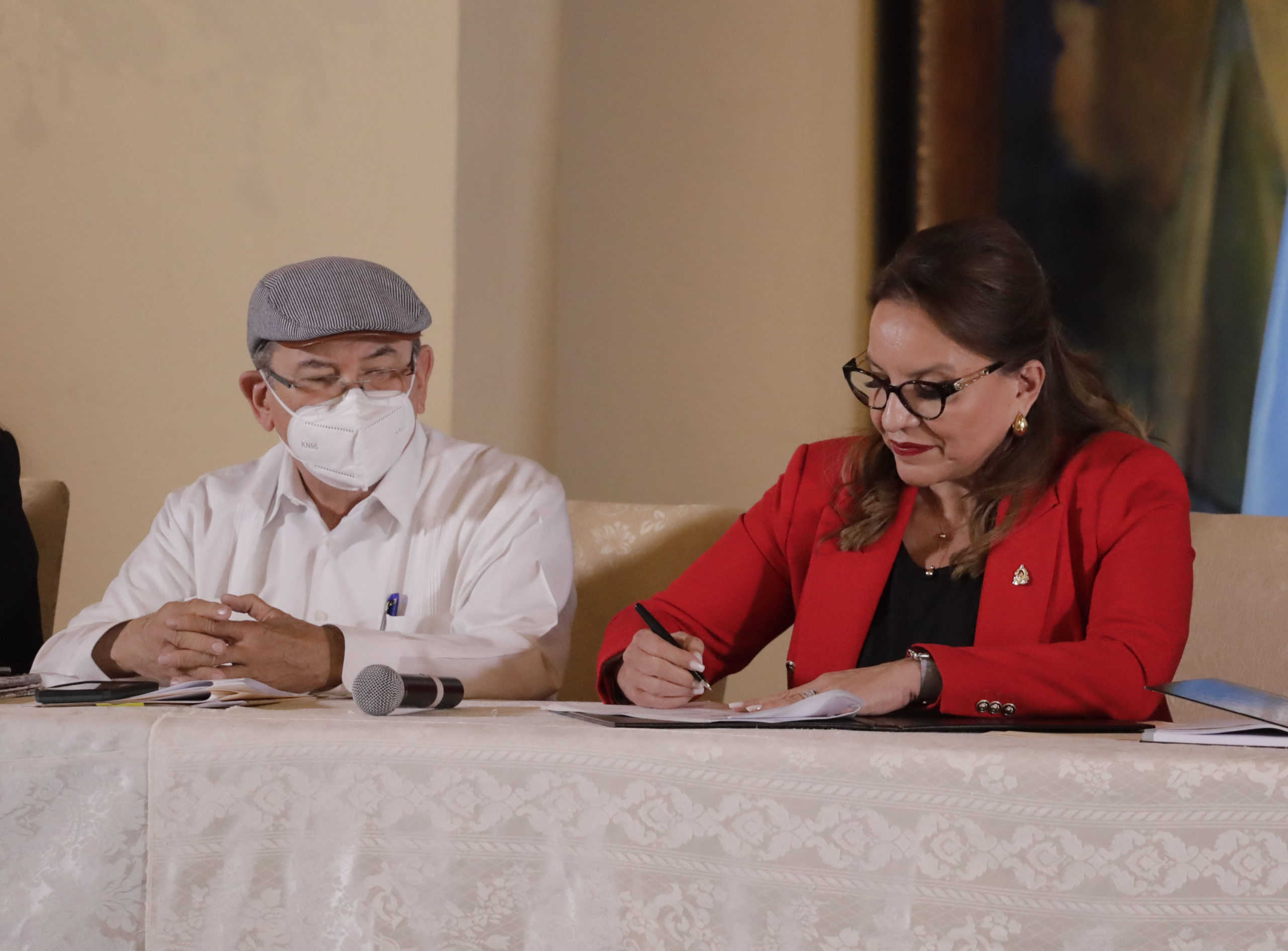

On April 20, the Law for Employment and Economic Development Zones (ZEDE) and other related decrees were repealed by the National Congress and ratified by President Castro. However, companies located in a ZEDE will now be directed by the Ministry of Development to register under one of the existing regimes for special economic zones.

César Benedith is president of the village council for Triunfo de la Cruz, a community of indigenous Garífunas. It was one of the first areas targeted by ZEDE investors and has had conflicts in the past with tourism projects. Benedith says that the repeal of the ZEDE law doesn’t solve the community’s underlying problems, “In addition to eliminating the ZEDES, we need access to financial resources for community development. Why? Because the ZEDES were attracted by all our undeveloped land. We have to develop these areas now before another government comes along and passes another law.”

Benedith said he was very supportive of the change in government, but that it’s discouraging to see so few Garífunas in government jobs. “I’ve always dreamed that the nine indigenous peoples of Honduras would be able to make demands and be properly represented [in government].”

While there may be a few Garífunas in the administration or the National Congress, Benedith doesn’t feel adequately represented because “they think like ladinos [the mainstream culture].” He says, “I’m looking forward to a more inclusive and democratic government where everyone has access to the Presidential House, not just the people in suits, where we are consulted about projects that affect us.”

President Castro also promised to focus on agricultural development and food sovereignty, and to order the Central Bank and the Ministry of Finance to create legal market mechanisms to lower interest rates on loans to agricultural producers.

Gustavo Rosa, president of the Catacamas Cattle Ranchers Association and former Catacamas mayor (the birthplace of the Zelaya-Castro clan), said that rural Honduras must be revitalized through concrete government policies. “There are problems with financing, for instance. The country is undergoing a serious jobs deficit. One sector that can generate jobs immediately is livestock and agriculture,” said Rosa in an interview with Contracorriente. He claims financing for this sector is being diverted to others who take advantage of low interest rates and the lack of government oversight.

Ramírez says that the government has only acted so far to reduce certain bank fees, “But those are consumer-oriented actions for those of us who use credit cards. They were talking about reducing interest rates for agricultural producers.”

ICEFI’s Ricardo Castañeda said that doing anything that affects powerful business interests will always be difficult. “A government that comes in promising change is obviously going to encounter obstacles. It’s going to face opposition from historically privileged sectors that aren’t willing to give up their advantages. To be successful, a democratic government must have the ability to dialogue openly with various sectors of society,” he said. Castañeda strongly believes that a government’s decisions must not be based on their popularity, but rather its decisions should be fact-based to ensure that they will improve public welfare.