Monserrath* suffered a miscarriage at her home approximately four months after being deported from Mexico. She had been sexually abused on the migration route to the U.S., but didn’t know that she was pregnant as a result. Despite affirmation that she did in fact suffer a miscarriage, Honduran prosecutors brought charges against her for allegedly committing parricide, which can lead to a 20 to 25 year prison sentence. She was acquitted by a jury in October 2023, but her life has not been the same ever since.

Text: Vienna Herrera

Graph design: Daniel Fonseca

Translation: José Rivera

English editing: Amy Patricia Morales

Monserrath suffered a miscarriage early in the morning on October of 2022, when the reality of what she had been through months before suddenly struck her; she was pregnant as a result of sexual abuse. Monserrath’s memory of what happened that day is like a labyrinth. She barely recalls a few details: She was in a latrine close to her home and there was a lot of blood, but her baby never opened her eyes and never cried. She was scared; she was only 18 years old and was responsible for her other child and had been recently deported. She didn’t want to explain to anyone what she was going through and was afraid that people would not believe her and that they would judge her.

Monserrath said she put her ear on her baby’s chest, waiting for a heartbeat, but she didn’t hear anything. “I asked God why, if I was pregnant why did he give me a dead child,” she said and explained with teary eyes that she put the baby in a bag.

The body was found several hours later. The community where she comes from is small, so everyone knows each other and news spread quickly. Monserrath found out when her younger brother-in-law showed her a picture, “Have you seen this? They found a baby,” he said.

Personnel from Forensic Medicine arrived approximately four hours later to remove the body. Within a 48-hour period, Monserrath was facing parricide charges.

She sits in front of the tribunal. She looks much smaller than the three male judges sitting in the bench; they’re all wearing robes and have a very serious demeanor.

The courtroom is small, and its location cannot be revealed for Monserrath’s safety. Some of her friends who arrived to support her were not allowed into the courtroom because they were wearing knee-length skirts, and there’s a sign that says that women should wear pants or skirts whose length is at least four inches under the knee, otherwise they’re not allowed in. A security guard approached the other women who attended the trial and had followed the dress code and told them not to cross their legs, to keep their knees close to each other and to sit up straight, “it’s what the judges requested to avoid distractions,” he said.

The prosecutors who brought charges against Monserrath look at her with contempt every now and then. She shrugs and puts her hands together to calm herself down; she’s going to give an account of what happened, again.

The hearing and the public trial were suspended weeks before because Monserrath suffered a breakdown knowing that she had to give an account of the events and that prosecutors were very doubtful that she was sexually abused. Monserrath, who had been diagnosed with severe depression, spent that night at the hospital due to the breakdown.

Before she spoke, the judges reminded her that she’s not there to prove her innocence and it’s up to the prosecutors to prove that the charges brought against her can be defended. They ask the two prosecutors to conduct the interrogation in a sensible manner and to take into account the defendant’s mental health.

The prosecutors, however, smiled at each other. A few minutes later, they ask her if she’s really a victim of sexual abuse. “Did you notice anything odd in your body such as any odd fluids? Did you feel any changes during the journey?” they asked. The defense objects and the tribunal reprimands the prosecutors. Then, they ask why Monserrath stayed at her mother’s house after being deported and not where she used to live with the family of her partner, the father of her son. They tried to instill doubt about the sexual abuse from another perspective.

Monserrath cries and explains that she was trying to process everything that had happened to her and eventually returned to her mother-in-law’s house, where her sister-in-law also lived.

Her sister-in-law is a witness at the trial and explained that her brother married Monserrath when she became pregnant at the age of 17. Monserrath’s partner migrated to the U.S., but he was a very controlling man. “He used to tell her where she could go and what she could wear,” said the sister-in-law. For this reason, Monserrath was afraid of what he would think about the sexual abuse. He asked her to go to the U.S. with their son, and she did. However, she didn’t tell anyone and when she got to Mexico, she was sexually abused. Shortly after, before arriving in the U.S., she and her son were deported to Honduras.

Monserrath’s sister-in-law noticed something different about her when she returned to Honduras. “She was different; she used to be joyful and funny and liked to do TikTok videos. Now, she doesn’t even go out to eat,” she said. Monserrath told her that she was raped and asked her to make a promise that she will not tell anyone, especially her brother. She kept the promise as a sacred oath, which she had to break at the trial.

For most of Monserrath’s first pregnancy, she was not aware that she was pregnant, so it’s no surprise that nobody, including herself, noticed the second pregnancy. The doctor who performed the forensic evaluation when she was detained said it was not possible to notice that she was pregnant.

Dr. Braulio Mercado—an obstetrician and gynecologist who was part of the team of advisors from Optio, an organization that disputes similar cases who represented Monserrath in the trial—explained that cryptic or silent pregnancies are more common than most people think; one in every 475 pregnancies is cryptic, and it’s more common in countries like Honduras, where structural malnutrition and adolescent pregnancies are present.

Charges against Monserrath

National Police began an investigation after the removal of the body. They went to the health center and noticed no pregnancies of the women under care were interrupted. They interrogated the medical personnel, and one of them said that he had suspicions about someone.

A few days before the miscarriage, Monserrath had a high fever and went to the same health center. The queue was long, and being there made her feel worse. Her son also needed her at home, so she left without seeing a doctor. The personnel thought this was suspicious and told National Police that she might have something to do with the body because she doesn’t live far from where he was found.

There’s no statistical data on similar cases, where women are accused of committing parricide, but another crime for which Honduran women who suffer miscarriages are prosecuted is abortion. According to the study Criminalization of abortion in Honduras, based on files of Honduran women prosecuted for abortion between 2006 and 2018, and carried out by Somos Muchas and Optio, most of the denunciations, 64%, come from staff in the public healthcare system.

Medical personnel are usually not involved in the legal process; they don’t testify in court, but they denounce the patients and violate doctor-patient confidentiality, an ethical obligation to protect patient information. The name of the person who denounced Monserrath was not disclosed.

Police arrived at the house to interrogate Monserrath and her sister-in-law, the only women of childbearing age living there. They were taken to Forensic Medicine for a medical evaluation. Monserrath’s evaluation took a long time. Her sister-in-law said that when she got out she was crying and told her, “Take care of my son as your own.” She explained that Monserrath is a loving mother, and her son is very dependent on her, which is why he suffered when his mother was detained.

Monserrath was detained and publicly exposed for allegedly committing parricide. Several media outlets revealed her name and photos wearing short clothes. Although legal actions against Monserrath had not concluded, media outlets portrayed her as guilty. As a result of this situation, Monserrath suffered more serious mental health problems; she wasn’t sleeping or eating and felt depressed. She was also diagnosed with anemia.

Monserrath received mental health services from Optio. She met with other women who had been prosecuted in similar cases and are now acquitted, and this helped her considerably to continue the process.

Evidence

One of the main issues with the charges brought against Monserrath was how prosecutors determined gestational age. According to them, Monserrath was 30 weeks pregnant, which was determined by the date of her most recent menstruation. However, Dr. Mercado, the obstetrician and gynecologist consulted during the trial, explained that the same data evaluated by Forensic Medicine points to a different gestational age.

He pointed out that there are several tests to determine the gestational age like Capurro and Ballard, but prosecutors didn’t perform any of them.

“Gestational age is important because a fetus can survive between the 28th and 32nd week of pregnancy with proper care. It’s very unlikely that a fetus would survive at the 28th week of pregnancy, and there are few cases in Honduras, but it’s possible,” he said and further explained that according to data from evaluations conducted by Forensic Medicine, the gestational age is between 22 and 28 weeks, an age that jeopardizes life outside the uterus.

Before pregnancy, the size of the uterus is between six and eight centimeters. As gestation progresses, it can grow up to 33 centimeters. Medical evaluations showed that the size of her uterus was ten centimeters, an amount of growth that is not indicative of the third trimester of pregnancy, which is what the prosecutors sustained in court.

Moreover, forensic evaluations showed that the uterus was five centimeters away from the navel. “That number increases to 15 or 16 centimeters in a full-term delivery. We can verify with the evaluations that it was a premature birth,” Dr. Mercado explained and added that the gestational age could be less than 22 weeks.

According to Dr. Mercado, these measurements should have warned medical personnel of the possibility that Monserrath could suffer a miscarriage, but additional tests to rule it out were not performed. She had a fever before the incident, but they didn’t take her temperature during evaluations, “Fever can point to a premature birth,” he said.

The Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) issued a sentence against the Salvadoran State in the case Manuela et. al vs. El Salvador. Manuela’s story is similar; she suffered a miscarriage at her home and was prosecuted for murder. The Court pointed out that one of the most serious errors made by Salvadoran prosecutors was to dismiss the presumption of innocence, which implied that “authorities should have pursued all lines of investigation, including the possibility that Manuela was not responsible for the death of the newborn by evaluating her health and its impact on childbirth,” the sentence reads.

Forensic training

According to the doctor who removed the body, the newborn was alive because he was covered with vernix caseosa, a dense white substance that protects the fetus’ skin while he’s in amniotic fluid, which starts to form between weeks 18 and 20 of pregnancy. According to Dr. Mercado, this is not an indication that the newborn was alive since it’s a characteristic of all pregnancies and it’s more visible in miscarriages because the coating is thicker as it starts to form and becomes thinner as gestation progresses. There are even some newborns who don’t have the coating at birth.

The doctor who removed the body says that she has five years’ experience in Forensic Medicine, but she hasn’t had similar cases and didn’t determine the gestational age because it’s not her responsibility. When a specialist from Forensic Medicine, who was consulted by the defense, asked her what temperature speeds up a body’s decay process—since she mentioned “warm temperature” in the report on the removal of the body— she responded that he should not have that information, and it’s the responsibility of the team performing the medicolegal autopsy to arrive at conclusions.

The doctor’s superior, who is the prosecutor’s expert consultant, asked her if she’s a mother. When she said yes, he asked if from her experience as a mother she can tell if a baby is born with signs of life or not. The question was objected to by the defense and the judges.

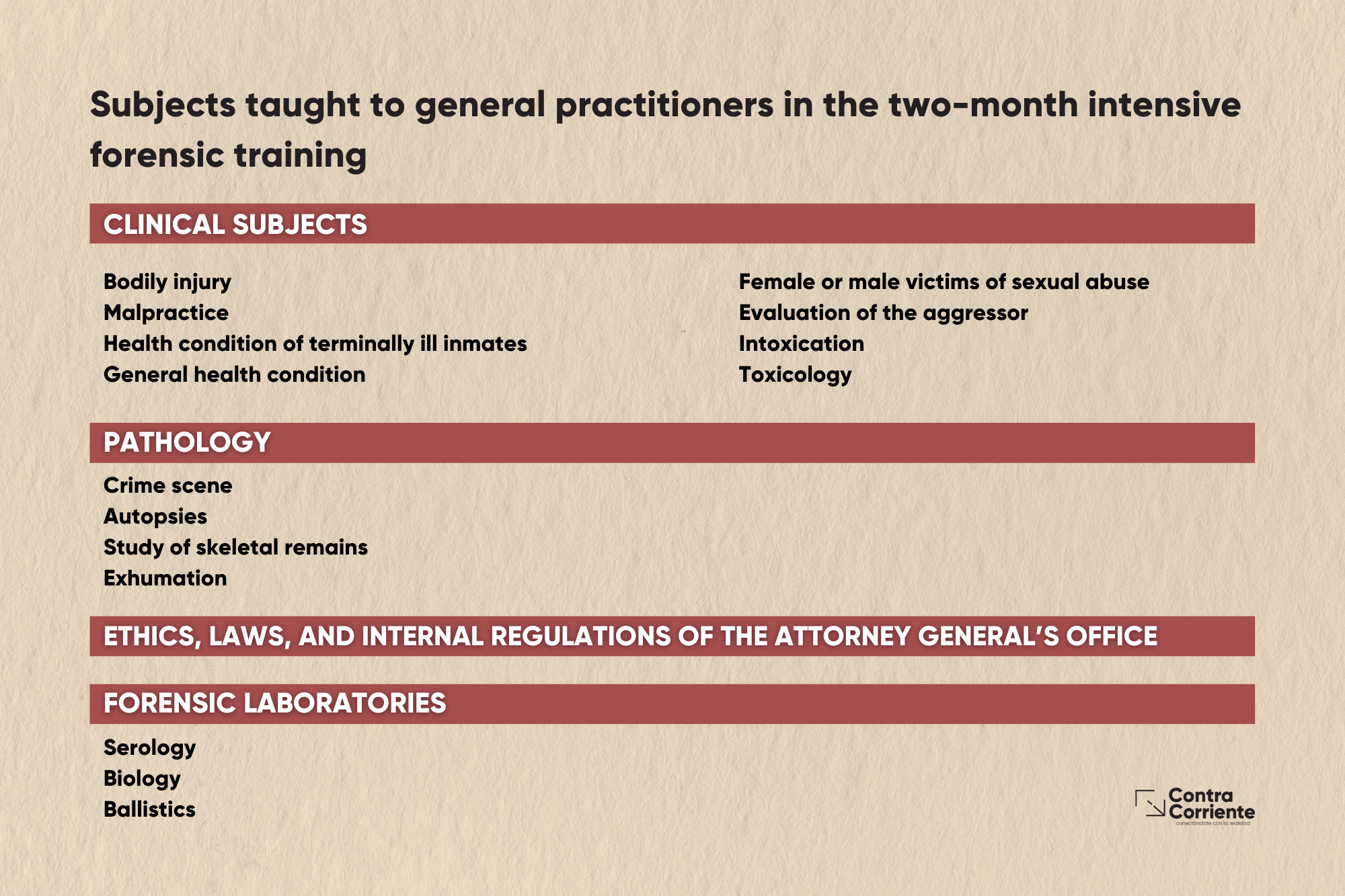

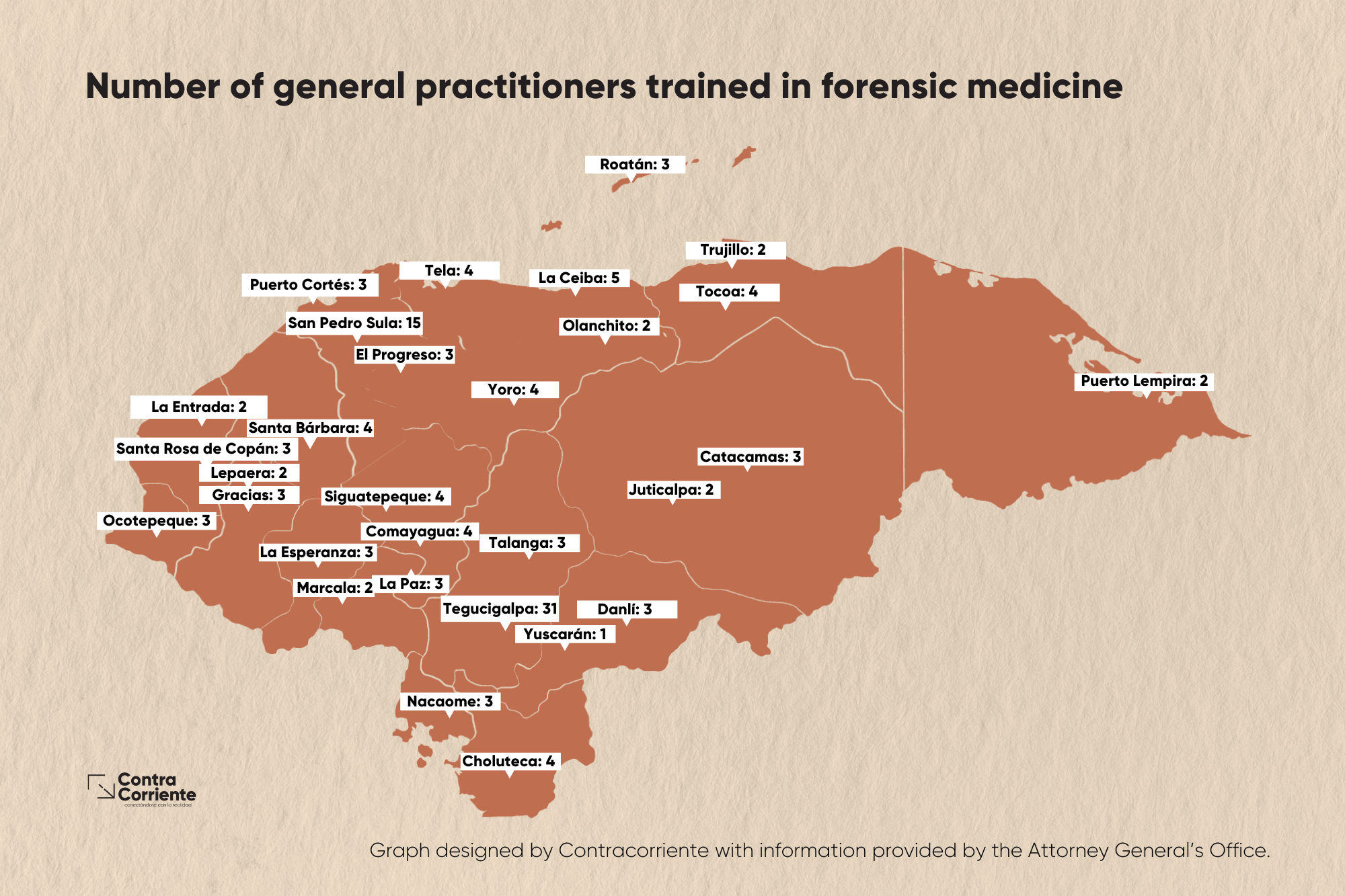

There’s an explanation for the shortcomings in evaluations conducted by Forensic Medicine. In Honduras, there are only a few professionals who specialize in legal medicine working in the public sector. There’s only five in Tegucigalpa and one in San Pedro Sula. The rest of the country is covered by general practitioners who receive a two-month intensive training on forensic medicine that includes several topics.

Although Honduras is one of the most violent countries for women in Latin America, there are registered cases of false accusations against women who suffer miscarriages. Perspectives on gender and forensic obstetrics were not taken into account in any of those cases.

According to data provided by the Attorney General’s Office, only eleven training sessions on femicide and gender and sexual based crimes were provided to forensic personnel, a total of 54 individuals including medical experts, forensic doctors and mental health professionals. Training on forensic obstetrics was not provided.

Autopsies entail fundamental tests with which prosecutors accuse mothers of murdering their own children. The lung float test—in which it’s considered that the newborn was alive if the lungs float in water due to air trapped inside—was performed during the autopsy to determine if Monserrath had murdered her child.

This test is questioned by the scientific and forensic community because it has been used in many countries, including El Salvador, to prosecute women knowing that the test can give false positives. For instance, air and other gases can enter a dead fetus’ lungs if he was squeezed through the birth canal, if doctors tried to revive him or due to decomposition and manipulation of the body.

Dr. Theodric Beck himself, who invented the test in 1823, wrote in his annotations that the mere floating doesn’t prove that the child was born alive. In 2020, the National Advocates for Pregnant Women in New York brought together 25 forensic doctors who signed a letter pointing out that the test is not scientifically reliable and it’s not an indicator of a child born alive.

Gabriela Girón, lawyer and part of Monserrath’s legal defense team, explained that the test is divided in four stages, but only one was performed during the autopsy, “They’re supposedly qualified to perform the test, but we notice that it wasn’t done thoroughly,” she said.

The Optio legal team in San Pedro Sula was involved in another case in which the gestational age was more than 28 weeks. The baby was born in a private hospital and died after two hours due to not receiving proper medical care. The mother, relatives and the doctor witnessed that the baby was born alive. However, a lung float test was performed and gave negative results.

Life after the trial

The sentencing tribunal acquitted Monserrath in October 2023. Despite the acquittal, Girón thinks that the trial brought to light a lack of gender perspective in the justice system “in the way the victim and everyone involved is treated, including experts, lawyers and personnel from the sentencing tribunal.”

Although the tribunal never doubted the sexual abuse, the prosecutors, “despite understanding these issues and knowing that Monserrath was sexually abused, omitted this fact to support the reports by Forensic Medicine,” Girón added.

Girón, who has represented other women facing criminal charges, says that the judicial process has a significant impact on their lives “because they feel trapped and stressed. Trapped in the sense that they feel exhausted by the process, which changes their lives completely.” In addition, family unity is affected because the community not only reproaches women who go through this process, but also their families.

“In the case of Monserrath, the community had so much hate for her. Some people said that if she’s not found guilty, they will slaughter a goat as a sacrifice and asked how someone like her could walk free from this,” Girón said.

Although Monserrath was acquitted, the judicial process has changed her life. She said that she’s facing an imminent forced displacement because the judicial process set her back in her studies and doesn’t have any job prospects. People in Monserrath’s community still think of her as the woman who murdered her own child because of the condemnation she received on social media and news outlets, a deficient public health system and legal actions that led to the hearing and public trial; none of this goes away with an acquittal.

*Monserrath’s real name was not disclosed to protect her identity.