Text by: Jennifer Avila

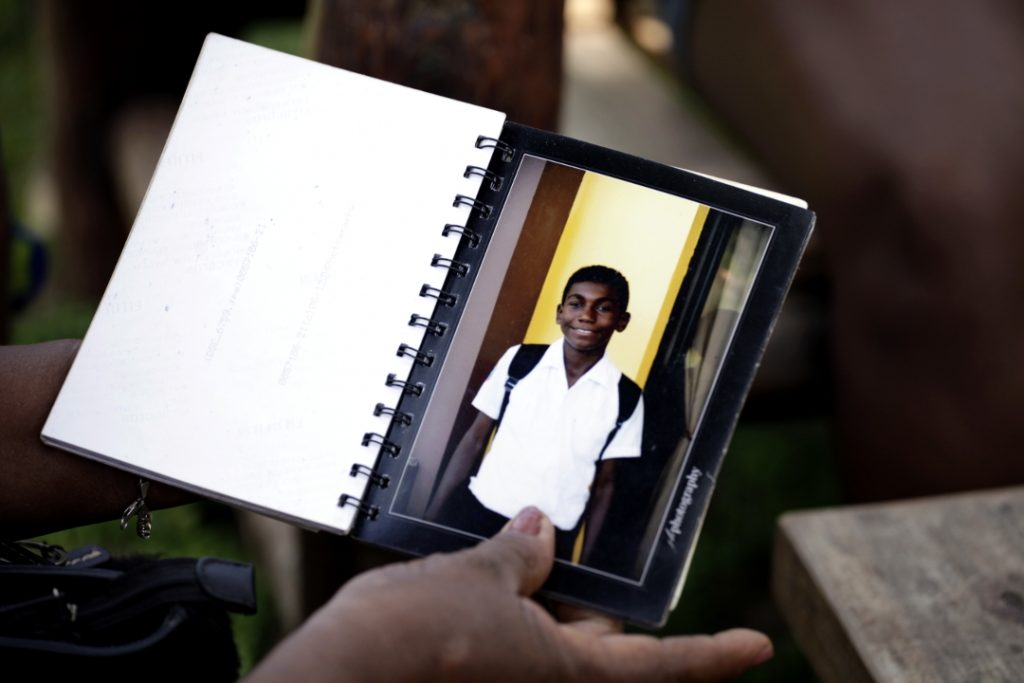

Photography: Hansel Brooks, victim in the Ahuas massacre 2012. By: Martín Cálix

Yesterday, a tribunal in La Ceiba absolved the only police officer on trial for the murder of one of the victims of the massacre perpetrated six years ago in Ahuás, Gracias a Dios. The accused was Alex Robelo, a member of the Honduran border police assigned to the Elite Unit of the American Embassy and the DEA in the fight against drug trafficking in the Honduran Moskitia. The policeman was accused of the murder of Emerson Martínez, the guide on the boat that was attacked, and was acquitted for lack of evidence in a trial plagued by racism and lack of diligence on the part of the Public Prosecutor’s Office.

The DEA’s collaborative program with the Honduran State in 2012 was known as the Foreign-deployed Advisory Support Team. Its members received military training to combat opium traffickers linked to the Taliban in the Afghanistan war, but was later expanded to Latin America in 2008 in order to combat transnational drug trafficking, and ended in the tragedy of Ahuás.

In May of 2012, four people died, one of whom was a pregnant woman. It was nighttime and a group of at least 16 Miskitos were traveling to Ahuás. The pipante, a traditional boat of the Miskitia, was full and led by Don Melanio, an old man from the town who worked with his wife as a sacabuzo, taking divers from Ahuás to the keys during fishing season. On his return, he gave the people of the community a ride. And yes, they traveled at night, which is very normal for Miskitos who, because of the sun, prefer to travel during the coolness of night.

At the time, the DEA said that the victims were traffickers who had attacked the agents and intended to capture a shipment of cocaine on another pipante that, at one point, had met with the victims. In the end, it came to light a couple of years later that the Inspector General at the Department of Justice, in his 424 page report, did not find evidence that supported the DEA’s version.

Read: DEA Misled Overseers on Deadly Honduras Operations, Watchdogs Say

But now, during this part of the judicial process, the Honduran court determined there was not enough evidence in this case. The defense for the police insisted throughout the trial that officer Robelo fired due to fear; it was a bad shot, and the bullet bounced and thus ended up crossing two ribs, the liver, and lodged into the heart of Emerson. And that is the only death that was accounted for justice, because during the exhumation, they managed to recover the bullet that was in his body and compared it, which determined that it came from a police rifle. But it could not be proven that the rifle was assigned to Robelo. In the midst of a hail of bullets that killed four people that night and wounded others, only one bullet could do some justice. But so much was discussed about the bullet that in the end, it could not be proven that it was fired by the officer who is now completely absolved.

“I just hope that justice is done,” the accused said bluntly, after the conclusions in which the public prosecutors along with the private attorneys asked for maximum conviction for simple homicide and for the crime of abuse of authority, while the defense asked for acquittal.

Robelo would be the third police to come out unscathed from accusations in this case. Noel Hernández, the officer in charge of the operative and Robelo’s boss, was provisionally dismissed in the preliminary hearing process and even served as a witness for Robelo’s defense. Also provisionally dismissed was Luis Vallecillo Cedillo, who is also a Honduran officer. None of these men have claimed to have seen a member of the DEA fire that night.

We recommend: Nosotros no somos narcotraficantes, que lo reconozca el Estado y la DEA

Living the nightmare again

The women relatives of the victims in Ahuás, the same ones who survived the attacks, cry when they tell the story as if it had happened yesterday. Six years have passed and the tears are still rolling. The pressure is on Don Hilda, Lucio cannot continue telling the story. All of the bereaved do not understand why it is so difficult to solve a case in which armed officers shoot at a boat full of unarmed civilians, and the civilians die. They die under a hail of bullets.

Clara Woods, a survivor and mother of one of the victims was called to testify at the public trial. She lives in Roatán and at the time, also lived there but would visit her mother in Ahuás. That evening, the day before Mother’s Day, she also took her son, her baby, 14-year old Hansel Brooks. Today, he would be 20 years old, but he did not survive. They found his body the next day, floating in the river in a state of decay.

When Clara approached the court in a room in a church, because in Puerto Lempira the judicial facilities were not ready for that trial, she began to speak her broken Castilian. The prosecution had to take a translator. It was a trial in the Honduran Moskitia about an event that happened in a small forgotten city where the people speak their own language. But justice was not ready for that, nor was the ombudsman. In addition to the revictimization that Clara suffered when being interrogated again and again because her Spanish was not understood, the defense accused Clara of being in collusion with drug traffickers, as if for that reason she would have to deserve the tragedy.

Clara says that night, they saw two helicopters fly by. They were used to those kinds of operations that the military had been carrying out since drug trafficking had increased in the area. They knew there was a war, but they did not feel a part of it. Before the trial, Clara talked to us. She was nervous. She spoke quickly between Miskito and Spanish. “There was a lot of fog. The young man (Emerson) was leading with focus. Then we heard 4 shots from the helicopter above that fired. Just like you all travel on the road at night, that is how we travel on the river. This has never happened before.” Clara heard the shots and quickly threw herself into the river. She could no longer see her son. The ones who could, jumped into the river. But others, like Emerson, remained dead in the pipante and others like her youngest son Hansel, her baby as she called him, remained floating in the river.

“I wanted them to kill me too. I yelled at them: you already killed my son and many other people.” But despite being wounded, Clara swam and reached mainland where she found Lucio, another of the young men who was in the pipante, was also wounded. They walked at night through a place with cows and a lot of grass, she remembers, and there they were met by military who wanted to arrest her. “I told them that they killed a lot of people who were coming on a trip. Then I heard someone saying ‘auntie, auntie’, and I saw my nephew laying on the ground handcuffed with black handcuffs on. And the military officer asked me what we were waiting on at the river so late at night. I was there because my nephew was waiting for me to help with some things I had brought, and the guy said ‘get out of my face’,” she recounts.

Robelo’s defense has a hypothesis: Clara is a narco-trafficker and communicated with her nephew who was waiting on the product, and that the pipante with the 16 people in transit was securing the river. Evidence that the defense tried to use was a deleted phone that showed that Clara called her nephew many times. The evidence was denied by the court, but during the trial it served as an excuse to say that Clara had communication with mainland at that hour, as if that were an illegal operation.

Clara says that she doesn’t understand why God saved her and not her son, “el seca leche”, who she now visits every time she can in Ahuás, where he is buried.

During the trial, they did a reenactment of the event in Ahuás. The group of prosecutors, experts, private attorneys, judges, defenders, and accused were transported by helicopter to the scene and the reenactment began at 4 pm. At the time that the two Honduran agents, Noel and Alex, went down a rope followed by an unidentified third party, they arrived at the pipante with the drugs, and according to the witness Noel, they were shot at by the pipante with the 16 passengers. They claim that it was unclear if the attack came from the pipante or from the mainland, where they later found forbidden weapons. But that made Alex shoot awkwardly, so much so that the bullet bounced and hit Emerson who died instantly. That said Noel, lost his visión after the shot, therefore his story is incomplete.

Throughout the night, the participants of the reenactment returned in a pipante with members of the army. There, they learned what it’s like to navigate the Moskitia at night. They saw various pipantes with people who had arrived from fishing, that were transporting the fish to their community. The hostility of the soldiers grew with these encounters. One of the boats had to find refuge in a community they passed by and when the military got out of the boat to ask for help, the community did not let them pass. They peaked through the door of one of the houses and when they saw mottled uniforms from inside, they did not want to open the door until they saw civilians. Just a few weeks before, the military had murdered three young Miskitos at night in a small community in Ahuás called Warunta. At this point, the Miskitos are feeling part of the war.

This trial in the middle of the Honduran Moskitia went unnoticed, while on the front pages of newspapers, President Juan Orlando Hernández appeared with Preston Grubbs, interim director of the DEA, holding hands and making deals to increase militarization in the Moskitia, because he already feels the pressure, says Hernández, from the drugs that are produced in South America and head to the United States.

Six years ago, Clara says, journalists from all over arrived to interview them. They traveled to Tegucigalpa and human rights organizations welcomed them, organized press conferences, and put the media’s focus on them. After that, they returned to their communities and forgot about them. Although, not all.

Shortly after the massacre, Clara says that a man took her to Tegucigalpa. He looked for her in her house in Roatán and took her to a place where they made her take a polygraph test.

‘That man told me to tell the truth, that Mr. Melanio fired from the pipante. I told him that I couldn’t say that because it was a lie. If Mr. Melanio fired, he would have had to stop the motor and he couldn’t have done that because we were going upstream. Then he told me that if I said this, he would give me $100,000. Then I started to cry. He told me that there was an American that came for me. Another told me that everything had been an accident. Then they removed the machine from my body and I went back.” But she could not mention in the trial anything referencing the role of the Embassy of the United States, the DEA or the Department of Justice, as if they were erased from the fact.

Lucio, who was barely 16 years old back then and was there with Clara, remembers that night that changed his life. “I speak because Ms. Clara has told me that I also have my word to say,” he begins his story.

“My wife was upriver and I went down to Barra Patuca to see my mother. The next day I went to Ahuás with Melanio. Nobody knew what was going to happen, not even with the noise of the helicopter did I imagine it until I heard the helicopter firing. I threw myself in the river and tried to pull myself up, but there was no way because I had already broken my arm, so I couldn’t. The bullet didn’t exit my body, so I suffered from this shot. I have many scars from it. I jumped in and I tried to swim, but when I did that, I felt that my arm wouldn’t move, only the other one below. It felt like my arm wasn’t working. I was scared because I asked God and he said nothing,” he says. Lucio was found later with Clara. He continues, and when he shows the scars and realizes he’s deformed, he cries.

“Now I can’t help my parents, I have a bum arm. Now I have two babies, but I’m like a baby because I can’t work. My parents are supporting me. I have suffered in this life.” A knot forms in his throat from the pain, interrupting his story.

Then Marlene Zelaya, the leader of the group of victims, interrupts. Marlene still has the videos of when they found her pregnant sister’s body in the river with Clara’s son on her phone. She shows us on her deteriorating phone and tells us, indignant, that these videos remind her that there is no justice.

“We are poor, we work in the mountains planting yuca. He did that,” and points to Lucio, who is crying with his head down. He can’t anymore. “He is very sad, obviously, all of us suffer because this pain is horrible. All the time it stays in our minds, never leaving. It’s a thing that you can’t forget,” says Marlene. She looked for Mirian Miranda from the Black Fraternal Organization of Honduras (OFRANEH in Spanish) to support them with the case. Thus, Ofraneh succeeded in including two private prosecutors at this stage of the trial. Ofraneh had also just provided legal support in the same way to the victims of Iriona, Colón, where two Garífuna people were murdered by members of the Navy in 2015. In this case, they succeeded in condemning 10 members of the Naval Forces. The same recipe of racism was present in this case.

The people are left traumatized, says Marlene. Helicopters scare them when they pass by. She takes care of the children that her sister left behind. One is already 15.

“I say that they would not have killed, they got confused between a drug pipante and one with innocent people in it. She,” pointing to Ms. Hilda, the wife of Melanio, “she was shot in the legs and can’t support herself. It is not worth saying, I seek justice. That is clear, but they don’t want to respond. They want to wash their hands,” says Marlene. She does not accept what they said in the trial or what the police witnesses said; that the Miskito people are “highly tolerable” of narcotrafficking, because Marlene does not even know the value of cocaine. And from her lost community, without basic services and ignored by the authorities, the only thing she knows is that drugs brought a war that she doesn’t understand.

The doubt of “Tiger” Bonilla

The Public Prosecutor’s Office summoned Juan Carlos Bonilla, a former director of the National Police who took the position in 2012 and signed an act that documented the types of weapons assigned to police officers. He arrived annoyed because he claimed not to know why he was summoned, that he did not know anything about the case and they made him travel from Tegucigalpa to the Honduran jungle to recognize a signature that in the end did not serve as necessary evidence to convict the accused policeman.

“The weapons are not controlled by the police director and at that time. I was not the director, but I signed because I was required, except I cannot say that the weapon was assigned to the officer,” the “Tiger” Bonilla said in the courtroom of La Ceiba when the court decided to resume the trial no longer in the Moskitia, but in the coastal city. Bonilla was known as a tough policeman, but he was also appointed by the same US Department of State in 2007 to participate in extrajudicial executions that he was never directly accused of. He himself, being the director of the police, had appeared implacable with the police purge, and there he was in the trial against an officer who was at his command, giving impetus to impunity. The Office of the Prosecutor did not request information from the National Property Unit, which has the inventory of weapons for official use. Thus, more proof that incriminated Robelo was lost.

Six years without justice

Hilda trembles when she remembers what happened that night. She and her husband Melanio returned to Ahuás after leaving the Miskitos that dive for lobster in the keys of Roatán. In those keys where they become crippled by the poor conditions of the water in which they submerge themselves. But this is the Miskito economy. They survive on agriculture and they make a few more lempiras from the fishing that can cost them their lives. Hilda and Melanio are higher up in the chain of the Miskito tragedy, they were sacabuzos and at that time, they had a pipante.

“I am a woman who has always liked working. I have worked for 20 years taking out divers to the sea. At that time, it was May 9th and I went down to leave 50 passengers, amongst divers and cayuqueros. The next day I went out at night. The moon was full. We were sleeping as usual. We were near the land of Paptalaya when we heard noises and heard the helicopters coming out. They did the shooting. As I was waking up, I heard four shots fired at the pipante and I got scared. I woke up and the helicopter shot at the pipante and when I felt the two bullets in my legs, I jumped into the water,” says Hilda who still can not move her legs normally.

After clinging to a branch, bleeding from her legs without any hope, she fainted and only remembers that she woke up in the Ahuás hospital. Her son rescued her in another pipante and they took her away.

A colonel recently assigned to Gracias a Dios told Contracorriente, on condition of anonymity, that drug traffickers operate like this: shield women, the elderly and children, and promise to get them out of poverty in order to help the drug lords reach the communities. They all go from drug dealers to human shields in the various versions told by the security forces, the only indication that the State exists in the Moskitia.

“I cannot work anymore. I used to work but not anymore. I almost do not travel because of this danger we’re in. When I hear bullets, I get nervous. I’m traumatized. When the bullets that fell come to mind, I think about how many fell into the water. God is so great that some were saved. They could have killed us all. God helped some of us,” says Hilda. She recalls that just a few weeks before it happened, Miskitos again fell victim to military bullets in Warunta, right there in Ahuás.

We recommend: Los nadie y una guerra por los recursos

Melanio, her husband, has his face cracked by the years and the sun. He does not speak Spanish. He is gone when the others speak. They accused him of having fired first.

“From where would I get weapons? I just wait for justice. The first days when the journalists came to interview me, I could not handle the nerves.”

The New York Times revealed that the DEA deceived the public, the US Congress, and the Department of Justice about that operation in Ahuás in 2012, in which commando agents were sent to Honduras.

In an official report, the DEA’s allegations that the operation had been led by Honduran agents were rejected. It ruled out the same thing for other operations in June and July of 2012, in which US agents shot dead traffickers who allegedly refused to surrender and went to take their weapons. In fact, the report points out that only DEA agents and not Hondurans had the necessary equipment to command the operation, such as direct access to intelligence. Instead of taking orders from the Honduran police, the agents gave “tactical instructions” to the Hondurans during the missions. And the stories about the three shootings show that the agency’s leaders in the country “made the crucial decisions and directed the actions taken during the mission.”

The DEA later did not cooperate with the State Department during the investigation of what happened in Ahuás and the internal investigation in the agency was nothing more than “an exercise on paper,” according to the report, because the FAST supervisor did not interview the involved and only collected written statements.

The DEA announced that it accepts the findings of the inspector general. The FAST program is over; it is the second time that the DEA developed and abandoned a military-style program in the hemisphere. Marlene helps Lucio to communicate and adds, “We all know that here it’s the military who are killing us, it’s not the drug traffickers. Before I could say that it was the drug traffickers. But no. I see that they themselves, the military, are killing. We do not trust the authorities very much because they are a double-edged sword. They only offer something but they do not uphold the law for the poor,” Marlene reflects before the trial in which she put her hopes. A trial where the policeman was exonerated and the lives of the Miskitos remain in a limbo of permanent impunity.