Several members of Indigenous communities, including leaders, who hold a peaceful protest in front of the Attorney General’s Office in Ciudad de Guatemala, asserted that they are guardians of democracy. However, they distance themselves from political and electoral struggles. The Attorney General’s Office and the Constitutional Court have undertaken a series of actions that jeopardize the inauguration of Bernardo Arévalo, scheduled for January 14, 2024. Indigenous leaders have said emphatically that protests are peaceful, ruling out any partisan or political motives. In fact, they want to avoid the conditions that led to the armed conflict in Guatemala that lasted 36 years.

Text: Leonardo Aguilar

Photography: Fernando Destephen

Translation: José Rivera

English edit: Amy Patricia Morales

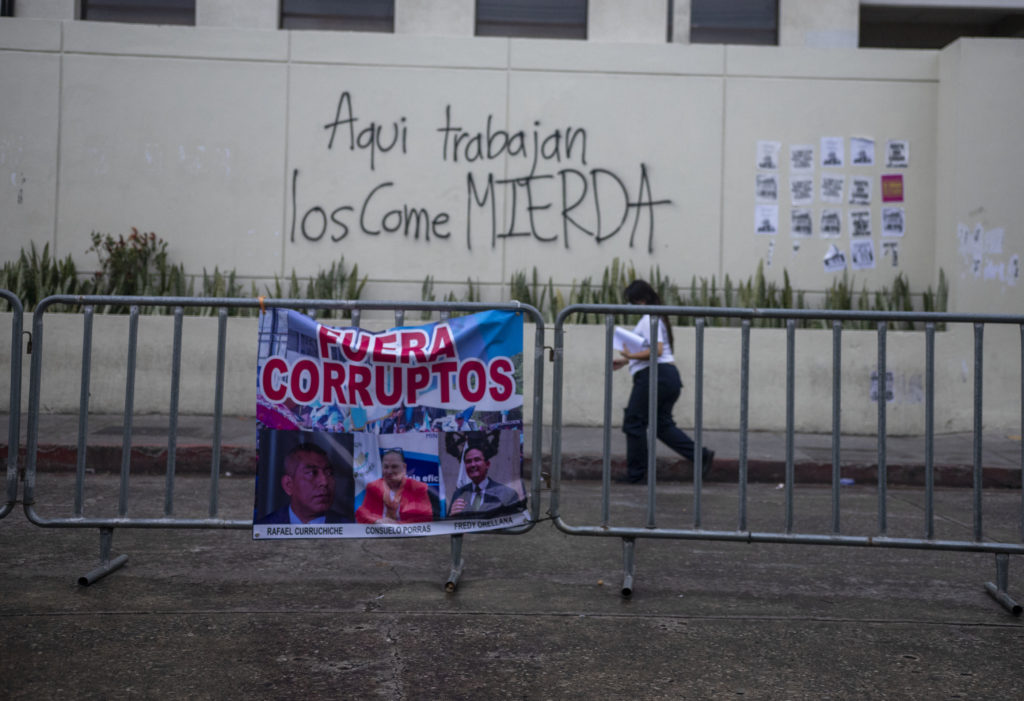

Light rain was falling on Ciudad de Guatemala, the capital of Guatemala, in the afternoon of Saturday, August 28. Hundreds of members of Indigenous communities had been peacefully protesting in front of the Attorney General’s Office for 26 days . The demand was simple: the resignation of four high-ranking public officials, including Consuelo Porras, the attorney general.

Many Indigenous people were drinking coffee, resting on mattresses and talking about their journey to the city from remote communities. Some of them come from Petén, the northernmost department in Guatemala, located more than 522 kilometers—a plus 10-hour drive by car—from Ciudad de Guatemala.

Inhabitants of Totonicapán, led by Concejo de Autoridades de 48 Cantones, ruling body and maximum authority of the Maya K’iche’ people asserted that the protest, during which at least 500 people took turns to surround the Attorney General’s Office in Ciudad de Guatemala, were absolutely peaceful.

Protesters were in the middle of the main street, as well as on its sides, where they set up tents, mattresses, food, an altar and a dais, from which—with loudspeakers—they gave euphoric speeches.

“I made friendships that I never thought I would. At the beginning, we were just about seven Indigenous groups and we’re 27 now,” an Indigenous leader said. His speech was clearly heard in the surrounding areas and was only interrupted by people shouting, who—with air horns, in the jubilation—celebrated the unity of the Indigenous movement.

Leaders of this movement asserted that the purpose of the protests—far from demanding support for president-elect Bernardo Arévalo and Movimiento Semilla, his political party—is to avoid a major confrontation in Guatemala. The movement is acting as a balance to demand and ensure that democratic principles are preserved.

Efforts by the Attorney General’s Office to overturn electoral results caused indignation in Guatemala.

After the results of the first round of elections that set Arévalo, who unexpectedly made it to second place, on the path to the presidency were announced, the Attorney General’s Office confiscated several ballot boxes. This set off the alarm among the Guatemalan population.

In mid-October, during a national strike that lasted several days to demand respect for the election results, one protester was killed and two were injured when armed men carried out an attack in the municipality of Malacatán, San Marcos, one of the plus 100 locations where peaceful protests were organized.

Recently, the Electoral Tribunal confirmed the suspension of Movimiento Semilla’s legal personhood after actions by the Attorney General’s Office and the Constitutional Court.

Main demand of the Indigenous movement

In addition to the resignation of Consuelo Porras, protesters are also demanding the resignation of the following public officials: Rafael Curruchiche, head of the Attorney General’s Office anti-impunity unit (Fiscalía Especial Contra la Impunidad – FECI); Cinthia Monterroso, prosecutor; Fredy Orellana, judge. These public officials—who are included in the Engel list, a list of individuals who acted undemocratically and were involved in significant acts of corruption released by the U.S. State Department—are accused of acting in bad faith and contrary to principles of Guatemalan democracy.

“We have a message for our Honduran brothers and sisters. This movement is led by all Indigenous peoples in Guatemala, from the Mam to the K’iche’. We all came together. What is the most urgent demand of the movement and the reason why we are protesting? The resignation of four public officials in Guatemala.”

Rogelio Pineda, mayor and representative of Totonicapán’s zone #4, told Contracorriente that the protests broke out because democracy was infringed upon.

“We talk about democracy as if it were simple, but it’s not because it encompasses many conditions throughout the country. I think that 48 Cantones decided to protest as a way to balance power in the country. Since democracy has been infringed upon, strengthening it is of paramount importance,” Pineda said.

According to Pineda, the four public officials, whose resignation is demanded, exceeded their authority and acted in bad faith. “We are talking about the authority of the Attorney General’s Office, which is not occupied by the way. We are simply resisting peacefully. Consuelo Porras is the embodiment of corruption. If we, Indigenous people, don’t act as a counterweight to balance power, they will continue undermining democracy in Guatemala.”

Pineda affirmed that the Attorney General’s Office in Guatemala has promptly investigated alleged irregularities that took place during the elections, but has ignored several high-profile cases that involve former presidents and other individuals who have political and economic power.

“And therein lies the imbalance and actions of bad faith. Of course, if there were irregularities concerning the votes, they should look into it. We’re not against that, but voter fraud is unacceptable and absolutely corrupt. They’re weakening the foundations of democracy.”

No one can explain the importance of 48 Cantones in Guatemala right now and its influence better than Pineda. He said that 48 Cantones was practically established in the aftermath of the Independence in Guatemala more than 200 years ago. Each time the organization presses its demands, “the balance of power is maintained in Guatemala.” Protests are now taking place around the country, it’s not just the K’iche’ people, to whom 48 Cantones belongs, who are involved.

“It’s tough, but if we don’t fight, who’s going to? Somebody has to do it, and we’re not just looking out for ourselves, we’re looking out for the future generations. Just as our ancestors taught us, we will continue to teach it. We have to be a people unified in resistance against any direct transgression against the common good of the general population.”

Pineda affirmed that well-educated professionals are essential to the movement’s success. “Many members of the organization are lawyers, engineers, doctors and architects. In other words, 48 Cantones cannot be considered ignorant. The people of Totonicapán, the K’iche, are more conscious than ever. I think that networking is important because it helps us strengthen our strategies.”

For years, protesters have demanded solutions to the energy crisis and issues concerning education, health, and Indigenous self-governance.

For instance, Pineda said that more Guatemalans have fallen into poverty since the privatization of the energy industry. “Guatemalans who live in conditions of poverty and extreme poverty were affected when the energy industry was privatized. It’s not easy for a family who lives on 50 or 60 quetzales ($6 to $8) a day and has three or four children to pay an electric bill of 20 to 25 quetzales. More than 50% of the family’s income is spent on electric bills, and this is the problem.”

Indigenous people are aware that Arévalo is not going to have the support of the Attorney General’s Office, the Supreme Court and Congress during his presidential term. “It’s going to be very difficult for Arévalo to exercise his authority as president in an equitable way and to enact any laws, but that’s why the strengthening of social movements is crucial.”

However, Pineda stressed that the movement is looking out for the well-being of the Guatemalan population in general, irrespective of who is in power. “We have never supported a specific political party. The fact that Arévalo was elected president is irrelevant. If someone from a different political party had been elected, and voter fraud had also taken place, we would still be here demanding respect for democracy,” he said.

Moreover, Pineda said that he’s aware of Arévalo’s family history. His father, Juan José Arévalo, was an iconic president from the period of democracy that began after the Revolution on October 20, 1944, in which Jorge Ubico, a dictator, was overthrown. However, Pineda affirmed emphatically that the Indigenous people of Guatemala will have to judge how Arévalo governs the country. “When 48 Cantones considers that actions by the government are unjust, we are going to organize and protest for the well-being of the population.” Pineda added that once Arévalo is sworn in as president, they will demand that the new government respects Indigenous people.

“That’s politics, and he will have to manage it well. So, I think that Indigenous people as a movement are valuable allies.” Pineda also acknowledged that consensus between the government, Indigenous movements and the private sector is necessary.

“That kind of alliance is necessary to have an equitable country. We should not fight with those who have economic power because they play an essential role in Guatemala’s development. If we are willing to fight with people who have the money, we’re off to a bad start. We simply have to talk and ensure that resources are distributed equitably.”

For now, Pineda made it clear that there’s only one urgent demand, “To ensure that Arévalo is sworn in. That’s the one thing we’ll guarantee.”

Indigenous authorities say that they represent the collective will of communities

Gladys Tzul, a sociologist, told Contracorriente that Indigenous resistance has significantly expanded in Guatemala in recent years.

She explained that there are two political systems in Guatemala, state and communal. The latter has a different electoral system, and different positions and responsibilities. The movement is not led by one person who decides about its future and its actions on a whim.

“Indigenous authorities called for a protest, but they represent the collective will of communities. There’s leadership, but they speak for all communities and not for themselves. Indigenous people from other regions of Guatemala gradually joined the protests; people from Petén and Izabal in the north, Chiquimula on the east, and other departments on the south coast. In other words, the movement is widespread.”

Tzu added that at one point more than 200 blockades were reported in Guatemala because the population went out to the streets on October 2. “That’s the day when protests began, October 2.”

Whether protests were spontaneous or well-planned and thought-out, Tzu says that since we’re talking about a political system that entails a deliberative assembly, protests were a measure taken by the citizens.

“Legal actions such as memorandums, court filings and petitions were sought at all levels of authority, but no action was taken, so protesting was the only alternative we had. I strongly criticize the idea that all of this was spontaneous because there’s no way that it could be. It was deliberate, and the decision was made by communal assemblies and authorities. Otherwise, protests wouldn’t have continued for 28 days.”

Tzu further explained the role of the Attorney General’s Office, an institution that should be impartial but it’s not. As a result, many communities are suffering, facing unlawful evictions and criminalization of their leaders, for whom arrest warrants have been issued.

“That also explains the generalized uprising, yes, to safeguard democratic order, so that there is a transition of power, but there is also that big umbrella that, if you think of your head in an umbrella, this is held by the rods, by the handle, then the rods and the handle are all these critical demands that the communities have made against the Public Prosecutor’s Office. The Public Prosecutor’s Office has been the institution that facilitates agribusiness, mining; that is why the communities of Petén are rising up to demand the resignation of[Rafael] Curruchiche and Porras.”

According to Tzu, the right of self-government is a historical demand by Indigenous people, and it’s important to emphasize that communities have handled the current situation quite well since they “stirred” the city.

“Indigenous people who live in the city started the protests and were later joined by the popular middle class because of the same structural conditions. What we see in the horizon is that Guatemala is supported by communal politics because funds for education, schools, highways and hospitals were embezzled. And who fought against this? Communities.”

In front of the Attorney General’s Office, Tzu said that Indigenous authorities have acted cleverly and changed strategies. “Indigenous communities had occupied the streets, but they’re now taking turns to protest in front of the Attorney General’s Office. For instance, my community came on Wednesday (October 25), and other communities came today (Saturday, October 28), so we’re taking turns.”

Tzu said that Indigenous authorities had made it clear that the movement is not about any political party, but rather about safeguarding democracy and avoiding conditions that existed during the war. In other words, the objective is to guarantee a democratic transition of power, and to ensure that the right to protest and to assemble are respected.

“So, I think that the movement is more broad in that respect,” Tzul said.

However, she argued that when Arévalo is sworn in, he has to be smart and understand that the population is a significant counterweight that balances the power held by the State. This was demonstrated during the plus 20 days that people went out to the streets.

“Arévalo should be smart enough to not intervene in the movement and at the same time to engage in dialogue.”

The struggle of Indigenous communities and a vision of gender

Doña María Juan Elías is deputy mayor, serves on 48 Cantones’ board of directors and is leader of a communal organization.

“I studied and then started working at an organization that supports communities in rural areas. I overcame the fear of speaking in public and learned to defend women’s rights. There are other issues that affect communities such as machismo and the lack of women participation in different areas of society, including decision-making. And that’s the reason why I fight.”

Doña María said she has been involved in leadership for 18 years and is currently fighting for the inclusion of women in decision-making.

“I’m inspired by the participation of women because we’re not just housewives, we’re also able to lead different groups. It’s important for a woman to have a job to support her husband, or if she is on her own, that she is able to occupy positions in committees to lead and make decisions,” she said.

Doña María experienced hardships when she began working in leadership positions. When her husband passed away, she had to keep working and raise her children.

“Those are challenges that I had to overcome. My children are now adults; they graduated from university and are working. They’re grown-ups and I don’t have the responsibility of raising children anymore. They take care of me now.”

Leadership and sacrifices

Óscar Rodríguez and Elizeo Yax are leaders in their communities. They also work in construction to provide for their families.

Rodríguez grows vegetables and other crops such as wheat and barley, but decided to do construction work to increase his income.

“I work in agriculture and in construction because it’s the only way I can provide for my family since wages are low. I’ve been married for three years and I’m a father now, but to earn a little bit more money and provide for my family, my wife and I had to make a decision. I mostly work in construction, but also in agriculture when I can put in extra hours of work.”

Óscar shared that he is committed to defending democracy and has the utmost respect for the authorities of 48 Cantones. He left Pacapox in Totonicapán for Ciudad de Guatemala at 2 a.m. and arrived at 5:30 a.m. “Mayors have always been elected by our communities, and we have always respected decisions made by the board and the council.”

Elizeo said that there’s considerable development in Guatemala, but corruption gets in the way of ensuring that everyone benefits. “The economy in my community is driven by those who migrated to the U.S., but we know that it’s a risky journey and people have lost their lives.”

Agriculture, Elizeo explained, is essential for his community and for Guatemala, and shared that the area of education and health care also needs improvement. To conclude, Elizeo explained that he’s protesting in front of the Attorney General’s Office not to support a political party, but because they’re eager for justice, one that is served equitably.

Although democracy dictates that Arévalo is going to be sworn in as president, nobody knows what will happen in Guatemala on January 14, 2024. The Indigenous people of Guatemala stressed that they are ready to organize and protest if authorities responsible for the democratic transition decide to act arbitrarily. This fits perfectly well with the following excerpt from the Popol Vuh: “Let everyone rise up, no one stays behind. It’s not one or two of us, it’s all of us.”