Protests by Indigenous peoples and environmental groups in Honduras have been taking place in Tegucigalpa to demand that the Xiomara Castro government fulfill its commitments, such as ending open-pit mining and destroying a drug smuggling road. The president has been silent, while her husband, advisor and former president José Manuel Zelaya, remains omnipresent and has even publicly mistreated a representative of Indigenous peoples. The protesters’ demands remain unheeded, while the Public Prosecutor's Office has opened criminal cases against some of them.

Text: Leonardo Aguilar

Photographs: Jorge Cabrera and Fernando Destephen

Translation by Ann Deslandes

On August 3, a group of 30 Lenca Indigenous people from western Honduras spent the night at the Presidential House to demand that the current government continue paving a 15-kilometer stretch of road, a project that has been suspended since the previous administration.

Six months had passed since Berta Zúniga Cáceres, coordinator of the Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (Consejo Cívico de Organizaciones Populares e Indígenas de Honduras, Copinh) and daughter of environmentalist Berta Cáceres, murdered in March 2016, gave President Xiomara Castro the Vara Alta Lenca, a sacred wooden staff that symbolizes Indigenous and Black women’s resistance to the dispossession of collective property. Zúniga Cáceres carried a small poster showing an image of her mother and the words “Berta will return and it will be as millions.”

In the initial days of her government, Castro promised to pay special attention to Indigenous peoples and to put a stop to resource extraction companies doing open-pit mining. Now, however, she remains silent while the protests of different Indigenous and environmental groups continue in Tegucigalpa.

When dawn broke at the Presidential House on August 4, it was not Castro who received the Lenca representatives of La Campa, Lempira, nor was it José Carlos Cardona, head of the Secretariat of Social Development (Secretaría de Desarrollo e Inclusión Social, Sedesol)’s ‘Nuestras Raíces’ (‘Our Roots’) program, which is aimed at promoting the development of the most impoverished areas of the country. Instead, it was President Castro’s husband and presidential advisor, former president José Manuel Zelaya.

During the meeting, Lenca Indigenous leader Darwin Reyes stood up, took the microphone and reverently addressed the former president, calling him “comandante.” While calling for the road to be completed, Reyes was interrupted several times by Zelaya. When he finished, all Reyes got was a monumental scolding from the former president.

“Comandante, I just want something,” said Darwin Reyes, “and excuse me, but we have been here from 12 o’clock at night until 6 o’clock in the morning.”

“Compañero, I have been doing this for 39 years,” answered Zelaya.

“You have only [been doing it] from 12 o’clock at night until 6 o’clock in the morning.”

But Reyes insisted, “Comandante, just one thing, we want you to order the minister to have the project ready by a certain date.”

“There’s no point speaking here, because I’m not being understood,” Zelaya answered, raising his tone, adding, “I thought you were getting what we are saying here. There is no money! Do you understand that? It’s pretty straight forward.”

Then Zelaya turned to the other Lenca people sitting across the table, “Let’s leave this one (Darwin Reyes) for a moment so he can see the light. Look, I already spent 15 or 20 minutes explaining, there is no money! If, objectively, there was, there is no way to extend all those roads that have been stopped … We can see all the effort the community is going to and that’s why we’re here, making a big difference.”

“Do you understand me, Darwin, do you understand me or don’t you understand me. This one is a little hard to understand. After all, he says he wants to be a politician,” Zelaya added, provoking jeers from the audience.

Our roots: Mel Zelaya’s program

Some Indigenous people call Our Roots (Nuestras Raíces) “Mel Zelaya’s program,” because it was Zelaya who convened leaders of the Garífuna, Miskitos and other Indigenous peoples. He also announced that the program would be implemented through the Solidarity Network (Red Solidaria), under instruction of the president.

Zelaya’s ascendancy in his wife’s government has been constant. In addition to his current role as advisor, at least ten officials of his government have been included in the Castro administration, this despite the fact that they had pending court matters.

The Ministry of Social Development is no exception: the current vice minister of Sedesol and executive director of the Solidarity Action Program (Programa de Accion Solidaria – Proasol), Olga Lydia Díaz, was director of the Family Allowance Program (Programa de Asignación Familiar, Praf) under Zelaya and, according to a report published in 2011, one of the promoters of the fourth ballot box referendum in Colón department. In February 2009, another report questioned her for signing a contract two years earlier that benefited businessperson Amilcar Bulnes via clauses that were detrimental to the interests of the government.

While there is no official information linking the president’s sister, Olga Doris Castro, to the current administration, Mel’s sister-in-law was coordinator of the Solidarity Network under his government. She also coordinated programs within the Zelaya government through which millions of dollars were administered after the cancellation of Honduras’ foreign debt in April 2005, under the Highly Indebted Poor Countries Initiative (HIPC). The aim was to assist some 200,000 of the poorest families in the country using 4 billion lempiras (at the current exchange rate, about US$162 million) through programs and projects. The study Honduras: What Happened to the PRS, published in 2007 by the Swedish International Cooperation Agency, revealed that out of 22 indicators of the Poverty Reduction Strategy (PRS), 11 were not met. Among them were the reduction of extreme poverty and mortality of children under five years old.

Our Roots program head José Carlos Cardona confirmed the influence the Zelaya family had in the past and defended Zelaya’s role, arguing that it was necessary to “illustrate the experience we had in those years.”

Cardona said the new Our Roots program is broader than the previous one, because it includes issues such as food security and sovereignty, intercultural education and ancestral knowledge, “plus advocacy, which is so necessary at this time.”

According to Cardona, talks have been held with 22 government institutions so that they “undertake works in the last quarter (2022) in the areas targeted by the program.” He also affirms that Sedesol has requested 200 million lempiras (US$8.1 million) for Our Roots in the 2023 federal budget.

As the past figures of Mel’s first government are re-appearing as heads of social programs under the Castro administration, the affected communities have their doubts.

Miriam Miranda, Garífuna leader and coordinator of the Black Fraternal Organization of Honduras (Organización Fraternal Negra Hondureña – Ofraneh), remembers the first version of Our Roots, “There came a time when people only came to collect money in briefcases,” she said, referring to corruption. “It was disgusting and now they want to keep doing that.”

These programs, said Miranda, are just seeking “to co-opt leadership in the communities.”

“How is it possible that they want to repeat a project in which there was wastefulness?” Miranda continued.

“We do not need populist projects that generate division in communities. Ofraneh is demanding respect for the ancestral rights of the Garífuna people … we do not want projects that are just more of the same,” she said.

Minister Cardona told Contracorriente and Redacción Regional that Ofraneh participated in recent meetings of Our Roots. Miranda denies this, saying, “I want to be categorical, put it in your article. Ofraneh through the voice of Miriam Miranda confirms that it is not participating in Our Roots. It is a replica of the previous program.”

Almost eight months after Xiomara Castro’s promises and during the first weeks of the implementation of the Our Roots program, the Garífuna, the Lenca, the Miskitos and the environmentalists of Guapinol have had to go to a lot of effort to travel to Tegucigalpa to demand that the promises be kept. Some of these groups have held sit-ins and read statements. They have even taken over the Public Prosecutor’s Office and forcefully entered the Supreme Court of Justice with the goal of being heard in order to stop the destruction of water sources, prevent extensive cattle ranching in protected areas, demand results regarding the disappearance of four Garífunas who were fighting against the dispossession of their territories, and stop discrimination against Indigenous peoples.

A drug trafficking road allowed by the government

While Mel Zelaya shouts at the Lencas that the government has no money to finish a stretch of highway in an impoverished area in the western part of the country, he quietly meets with powerful cattle ranchers from La Mosquitia, in the eastern part of the country, to authorize the continuation of a highway that many say is a drug trafficking corridor and which crosses the protected area of the Río Plátano Biosphere, listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site.

As part of the Our Roots program, on August 15, the government invited a group of Indigenous Miskitos, who came to the Presidential House from the department of Gracias a Dios, one of the most difficult areas to access. Once again, the former president was the protagonist of the meeting, this time together with Minister Cardona, the health minister, José Matheu, and private secretary Héctor Manuel Zelaya, son of the presidential couple. According to the government, this was the third ‘multicultural dialogue’ and representatives of 15 territorial councils participated.

“I did not participate,” says Miskito leader Passyn Dolly, “I represent the Departmental Council of Elders of the people of La Mosquitia. I don’t feel that the project is really an investment project for the development of La Mosquitia, rather I feel that it is a space to entertain the Miskito population, while other damage is being done.”

Dolly added that the organization Muskitia Asla Takanka (Masta, in Spanish, ‘Unidad de La Mosquitia’), and the 12 territorial councils are against the continuation of the road.

Dolly maintains that Mel Zelaya wants to “grab our lands and invade us with as many people as possible.” At stake is 98% of the resources of the Río Plátano Biosphere. “The government is dividing the people of La Mosquitia so that they kill each other, fight and live in social chaos,” Dolly adds.

The Miskito people were the first to travel to Tegucigalpa during Xiomara Castro’s administration to denounce the government’s broken promises. At the end of March, Lucky Medina, secretary of the Environment Ministry, promised to destroy the narco-road that connects Olancho department with Gracias a Dios. The work was inaugurated last year under the government of Juan Orlando Hernández, but construction began in 2007 when Mel Zelaya was president. One month later, Mel sealed a pact with the cattle ranchers of that area. According to the signed agreement, in exchange for stopping the destruction of the road, the ranchers in the eastern zone committed to stop extensive cattle ranching.

Masta says that the cattle ranchers have not stopped. Just after the deal between them and Zelaya, the former president said in Tegucigalpa that even the military have grabbed land and are beginning to form part of this group of ranchers.

Contracorriente and Redacción Regional tried to contact Medina, to ask for an explanation as to why former president Zelaya reversed his promise to destroy the road. Medina did not respond to calls or messages.

Zelaya was also contacted and via a WhatsApp message, he asked us to send him the questions in writing. After we sent them, he cut off communication.

Mining, violence and contaminated water

Protecting themselves from the sun with hats and visors, hundreds of environmentalists from five Honduran cities arrived in Tegucigalpa on Tuesday, August 16 to stage a sit-in in front of the Environment Ministry building. The protesters took a stand against water contamination and violence caused, according to them, by three mining companies: Canteras y Más, Inversiones Los Pinares and JAMART. ‘Water is life, no to mining,’ read a huge red banner held by four men.

The group of environmentalists from Colón and Olancho went to the National Congress where they demanded the repeal of legislative decree 252-2013 that legalized mining concessions in Carlos Escaleras National Park, the source of 34 rivers that supply the municipalities of Gualaco, San Esteban, Bonito Oriental, Tocoa and Sabá.

“We are no longer going to be able to drink water, no one bathes in the river anymore, because the miners are up there causing a disaster. If they don’t leave, we will leave the country. We will have to migrate,” shouted one of the demonstrators.

On the day of her inauguration at the National Stadium in Tegucigalpa, Xioamara Castro presented a list of 22 urgent measures for the “re-foundation of Honduras” in the first 100 days of her government. Among them was to grant “no more permits for open mines or exploitation of our minerals, no more concessions for the exploitation of our rivers, watersheds, our national parks and cloud forests.”

On February 28, the Environment Minsitry declared Honduras a territory free of open-pit mining, but, as would happen with the narco-road, the entity soon reversed that decision, arguing that more studies were needed of each particular project. According to a report published in El Heraldo, Secretary Medina said last March that large mining emporiums located in Honduras will continue to operate in the country under strict supervision. Among these, the multinational Aura Minerals and the company Los Pinares, have open-pit mining licenses approved by the government.

According to Contracorriente’s platform Abriendo Datos, Honduras has granted more than 1,500 mining concessions, the majority since 2012. There are 73 protected areas in Honduras, of which 21 are national parks; of those, hydroelectric or mining companies have active concessions in at least five of them.

Xiomara Castro has mentioned that she supports environmentalists from the community of Guapinol, who in the last four years have experienced a socio-environmental crisis due to the installation of a mine in a protected area. Eight of them were imprisoned for 40 months, accused of the crimes of aggravated arson, unjust deprivation of liberty and damages against the company Inversiones los Pinares. The president even used the slogan “freedom for the political prisoners of Guapinol” during the campaign and when she took office. However, the Los Pinares mining company continues to operate.

We recommend:The hidden connection of a U.S. steelmaker to the controversial Los Pinares mine in Honduras.

Garífunas take over the Justice Ministry

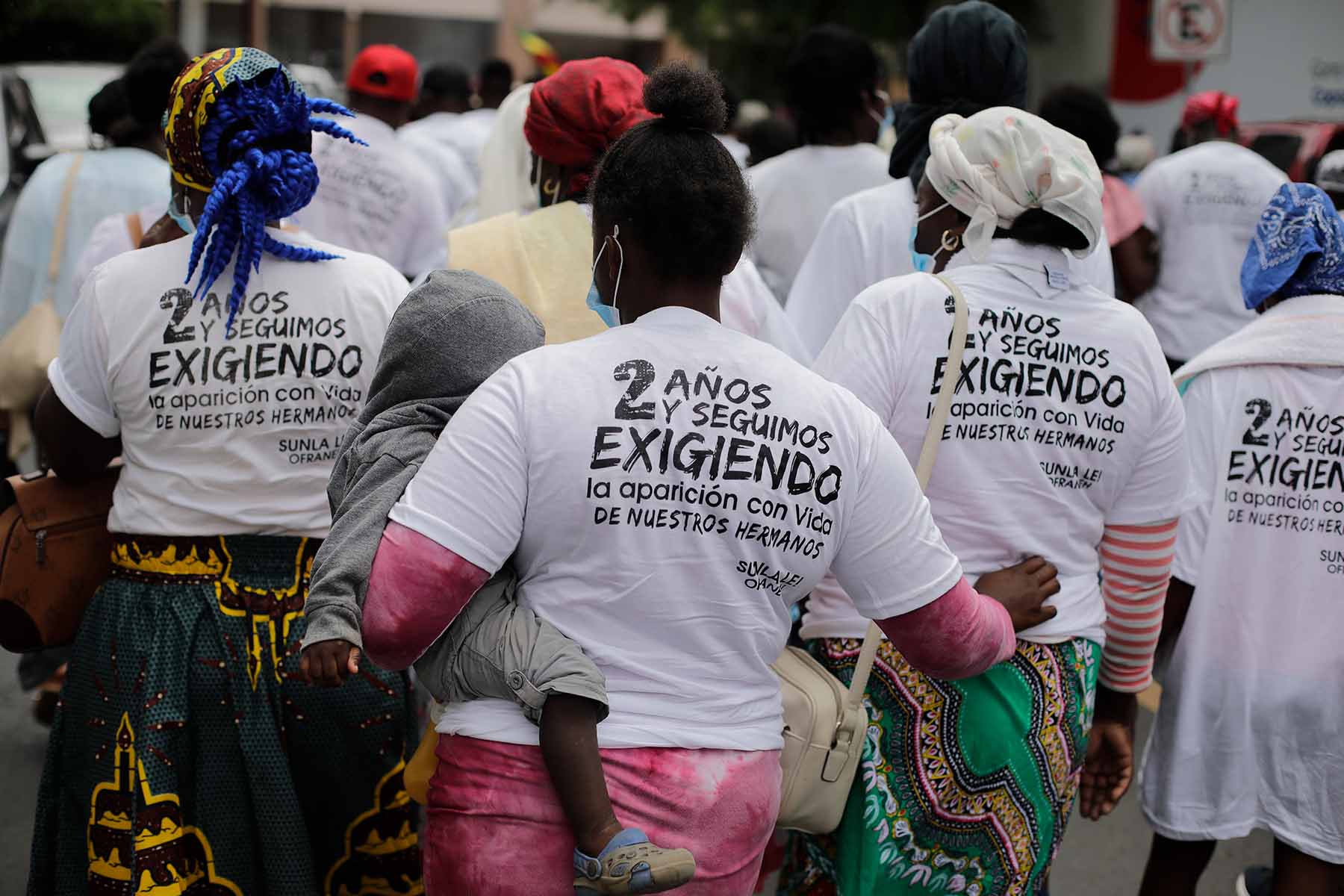

On August 9, a week after the first outreach between the government and Indigenous Lenca, at least 300 Garífuna, accompanied by some Lenca — including members of Copinh — and Tawahkas, traveled from the Caribbean coast of Honduras to Tegucigalpa. Instead of going to the Presidential House, they went to the Justice MInistry to demand answers after two years of the forced disappearance of four members of their community.

The Garífuna protest was an unprecedented event. The group entered the Justice Ministry and went to the door of the office of the Attorney General, Óscar Fernando Chinchilla, who did not come out to meet them.

“There is no political will from this government to recognize the rights of the Garífuna and Indigenous peoples,” said Ofraneh co-ordinator Miriam Miranda during the protest.

The Garífuna demanded the creation of a special prosecutor’s office to investigate the forced disappearance of these four Garífuna. Far from opening a dialogue between the Garifuna and the Justice Ministry, there is now a criminal investigation against Miranda, lawyer Edy Tábora and Luther Castillo, an official with the Ministry of Science and Technology. Ofraneh also denounces “investigations against other leaders who participated in the activity, in a shameful action of political persecution” according to a communiqué published on August 17, 2022.

A day later, Copinh announced on social media that a space for agreement had been opened between its organization and the Honduran government to “provide a solution to the historical abandonment of the Lenca communities by the Honduran state.” Berta Zúniga Cáceres, coordinator of Copinh, and cabinet secretary, Rodolfo Pastor, were present at a roundtable created for this purpose.

But while Copinh is trying to build bridges with the government, it is no stranger to persecution. On August 19, 2022, the organization shared part of Ofraneh’s denunciation with its networks, saying, “Once again we are making a statement to make it clear that if the Justice Ministry thinks it is going to intimidate us with these acts of criminalization it is wrong. We will continue to fight for the restitution of our ancestral rights.”

Ofraneh is not stopping either. In the midst of the Justice Ministry’s threat, they continue to demand justice for the disappeared. A week after the protests, they filed an appeal against the Attorney General, Óscar Chinchilla and the Deputy Attorney General, Daniel Sibrián; an injunction before the Constitutional Chamber to continue the investigations.

The National Congress of Honduras will begin a process to choose the next Attorney General, since the current one, Óscar Chinchilla, will leave office in September 2023. The same applies to the current 15 magistrates of the Supreme Court, who will finish their seven-year term in February of next year.

Edy Tábora, Ofraneh’s lawyer, said the state cannot look for the Garífuna while believing that they are dead. It has to search for them on the assumption that they are alive, which is one of the most important international norms in addressing forced disappearances.

In spite of the fact that the Justice Ministry continues to be led by the prosecutors elected by the previous Congress, the new government has not declared its position on the protests carried out by Ofraneh.

Miriam Miranda has the same message to President Xiomara Castro as the Lencas, the Miskitos and the rural workers in Toco, “I believe that the president appointed by the country must assume her leading role. We join the voices that say “we want Xiomara,” we women want her to be a protagonist, to assume her role as president, to respond to a people who are hopeful in this new government that voted for her in a landslide, as a result of being fed up with 12 years of dictatorship.”

*This report is part of República Finquera, a project covering authoritarianism in Central America and Mexico by Redacción Regional, an alliance of media and journalists in the region, including Contracorriente.