Text: Jennifer Avila and Danielle Mackey

Photographs: Jorge Cabrera and Fernando Destephen

Fact-checking: Celia Pousset

Translation by Ann Louise Deslandes

At the entrance to the Metropolitan Preventative Police Unit (Unidad Metropolitana de Prevención – UMEP) in the city of Trujillo in northern Honduras, once the haven of the drug trafficking cartel ‘Los Cachiros’, a vehicle with more than a hundred large caliber bullet holes sits on display.

Tourists take pictures with the car on the sidewalk, where officers go out to smoke a cigarette in the summer afternoon heat.

Deputy Commissioner Cristobal Muñoz welcomes Contracorriente to the police unit, known as UMEP 19. It is the most recently created by the Xiomara Castro government as part of a process of restructuring the police forces in Honduras.

Muñoz told us that while 350 police officers are needed for the proper functioning of his unit, he currently only has around 50. He said he expects that number to be made up by returned officers who were ‘loaned’ from the police forces to guard the country’s penitentiaries.

That is: in April, President Castro ordered the penitentiary centers be placed in the hands of the National Police after an intervention by the Armed Forces in 2019. The deputy commissioner explained that preventative police have been covering the posts temporarily, pending new penitentiary officers who, most likely, will be the police officers that were purged from the institution 6 years ago.

In 2016, the Special Commission for the Purification and Transformation of the National Police (‘Comisión Especial para la Depuración y Transformación’) was created in Honduras. The Commission purged approximately 6,500 police officers, of which 33% were referred to the Public Prosecutor’s Office for investigation. With the arrival of the new government, approximately 1,000 of the purged police officers sued the State, claiming they had been illegally removed from their posts. Meanwhile, the police are charged with facing the violence in the country and fulfilling the electoral promises of transformation and demilitarization of public security during the new government.

Deputy Commissioner Muñoz was recently named head of the unit in Trujillo. He was previously assigned to the city of Olanchito in northern Honduras, where his mission was to get homicide numbers down, which he claims to have achieved. “You won’t believe it, but it was the power of prayer,” he said, noting that he always told his police officers to ask God for help in the face of escalating violence.

A failed cleanup

On July 1, 2022, the Castro government inaugurated a community police force as part of a security strategy aimed at lowering the number of homicides through prevention activities. The mission of the community police is to involve communities in citizen security roundtables, which will support the preventative police, such as UMEP 19.

The inauguration events were enlivened and organized with funds from the G.R.E.A.T. (Gang Resistance Education and Training) program, funded by the U.S. government. This program has been operating in Honduras since 2012.

The importance of US support for the police in Honduras remains high. In March, the police director, General Gustavo Sanchez, told Contracorriente that the restructuring of the police forces was underway, and a readjustment of the budget was necessary since the current one was insufficient for the situation in which the institution finds itself. Weeks before, the national general budget assigned 7,850 million to the Security Office and 9,336 million to the Defense Office.

Sánchez is under the command of Security Minister Ramón Sabillón, the first police officer to assume that post in Honduras.

Sabillón and Sánchez share much more than the vision of a new police force. Both were in the US during the government of former President Juan Orlando Hernández, extradited for drug trafficking. Sabillón was in exile and Sánchez was appointed as police attaché in Washington. Both said they were persecuted for not aligning themselves with the Hernández government, whose main security objective was to weaken the civilian national police.

“We are redistributing the resources we have, but we need more. Eighty percent of the budget goes to salaries and wages, but the Armed Forces have almost 10 billion,” said Sánchez.

“In Honduras there is not a defense problem, but a security problem,” he added.

According to the general, the police purge that was promoted after several murders involving active members of the National Police was a flawed process that is currently costing the Honduran State millions of dollars in labor claims.

“There have been 7 purge processes,” explained Sánchez.

“The last was a flagrant violation of the constitution and its laws that should not be repeated,” he added, noting that the state ends up being responsible for lawsuits.

“Oversight mechanisms must be created, yes, but in this way with all institutions. At this moment I am responsible for the continuous purging process,” he said.

According to Southern District Court of New York documents from a case against Fabio Lobo – son of former President Porfirio Lobo Sosa – in August 2016, the US government requested legal assistance from the Honduran government to seek, among other things, investigative files and evidence held by the Special Commission for the Purification of Honduras as well as reports from this same commission related to the defendants. The case documents show that the following year, the government learned that its Honduran counterpart had not responded to the request despite its urgent nature.

Illegal activity by members of the police has been widely known to the Honduran population. Figures such as former national police chief Juan Carlos ‘El Tigre’ Bonilla, now extradited to the US for drug trafficking crimes, were feared for many years.

“General Bonilla had already been tried [in Honduras] and got off scot-free. The state institutions failed with the whole narco-state structure that was functioning,” Sanchez contended.

Minister Sabillón, who has gone down in history as the first police minister to capture a former president, returned to Honduras a few days after Xiomara Castro won the November 2021 elections. Looking for a new chapter in his story, a long-bearded Sabillón appeared before the media and made himself available to the new government.

After more than 20 years of a police career, now in his minister’s office, he said the national police does not need another purge.

Sabillón, who was also the person who placed the handcuffs on former President Hernández when he was captured to be extradited to the United States on drug trafficking charges, said the extradition of a former police director ‘raised the image’ of the police in Honduras. It sends the message that “no one is protected,” and “whoever participates in crimes, pays.”

“The extradition warrants of the past were not executed. We are doing it, and we even went after a president.”

Sabillón emphasized that the current government is generating more confidence among the population. Even so, he said, external support is fundamental.

In the previous government, said Sabillón, the police were “treated… in a dehumanizing way.”

“I suffered it.”

“If we said something against the system they fired us, if we did not keep quiet they killed us.”The previous campaign to purge the police in Honduras was “illicit” and based on a “false flag,” Sabillón continued.

“[It created] a social and public hatred against the institution…[it] maybe had a little bit of good intention because there were bad policemen, but maybe it was 1%, and [one should not] fire 5000 people because of that.”

The concerns of the minister and the police director are far removed from those of Muñoz in Trujillo, who day to day has to cover one of the regions of the country most affected by drug trafficking and agrarian conflicts with very few police officers. The structural precariousness of the institution and the accumulated loss of prestige due to far-reaching corruption rest on his shoulders.

In April 2022, three police officers recently appointed to Muñoz’s UMEP 19 were killed on an African palm [trees used for palm oil] farm while chasing a suspicious vehicle that failed to stop in a police operation. Muñoz said that the case of the agents was something unusual. He said that the police officers were returning from filling their patrol car with fuel and “mistakenly” followed the suspicious vehicle. A mistake, said Muñoz, because there are roads where police officers know they cannot be trusted and these officers were careless, a chance occurrence. So far, the case has not been resolved, however, President Castro decreed a state of emergency in the area for ten days. The days passed, but the police unit in charge of this state of emergency continues to be active.

Currently, the Police has the challenge of cleaning up its image after the extradition of Bonilla, the prosecution of several members of the institution involved in drug trafficking cases investigated by the U.S. Attorney’s Office of the Southern District of New York and the questions that continue to be asked about violent events in Honduras in which police officers on duty are involved.

On May 29, a young man was killed by police officers in a sting operation after he assaulted a policewoman during a soccer match. Further, on July 15, there was a massacre in which 4 young people were killed, one of them the son of former president Porfirio Lobo Sosa, and in which the perpetrators used police clothing and weapons. And, in an entrance test for aspiring police officers held recently in the facilities of the National Police Academy (ANAPO), mistreatment was reported, which has already resulted in the death of four people without there being, so far, a deduction of legal responsibilities within the institution. All these cases are still under investigation.

These cases do not tell us anything new, since the Southern District Court (SDNY) showed that Honduran politicians play a key role in the drug trafficking business; but it also showed the high levels of corruption in the country’s police institution.

The police: a key part of the narco-state

It was during the investigation of an armed attack in 2004 that Carlos Alberto Valladares Zuniga, then head of the homicide division in San Pedro Sula, met Leonel Rivera, a drug trafficker.

Valladares had been an officer for a decade and was on an upward trajectory, just a year after being named police chief in the city of El Progreso and winning an award from the US Embassy for his work fighting criminal groups such as gangs.

However, one decision turned his trajectory upside down. Valladares agreed to receive a bribe from Rivera, a member of Los Cachiros, to stop the investigation against him and let him go free. To achieve this, Valladares pressured the victim’s girlfriend so that she would not press charges. Thus began a mutually beneficial relationship that became increasingly lucrative in the years that followed as Rivera and his brother built one of the most important drug trafficking empires in Honduras.

In a phone call one day in February 2017, the officer and the drug trafficker reminisced about their years of collaboration. Valladares reminisced about the half-dozen times they both traveled to Tocoa to help with drug shipments, trips on which he brought his service weapons to provide protection. He recalled the various ways he helped solve Rivera’s problems, for example, when in 2012 the pregnant wife of Rivera’s cousin was killed after leaving a bank where she had cashed a check. Valladares used his authority as a police officer to obtain the bank’s surveillance video and helped find the two alleged killers. He was present with a group of more than thirty police and narcos the day the cartel kidnapped the assassins from a business in Tegucigalpa. From there, Rivera’s men took the two assailants to a farm and tortured them to death.

The officer recalled coordinating with a former regional director of the Administrative Office of Seized Assets (Oficina Administradora de Bienes Incautados – OABI) in San Pedro Sula to allow him and other police officers access to the place where one of Rivera’s pickup trucks that had been seized in an anti-narcotics operation was stored. Once there, in exchange for a payment of $80,000 each, the police officers removed 100 kilograms of cocaine from the seized vehicle. He also recalled when he was with Rivera and Fabio Lobo, son of an ex-president, waiting for a drug plane to arrive in Omoa, Cortes, and Lobo, not very patient, pushed Rivera to get them closer and closer to the airstrip.

What the policeman did not know the day he expressed all those memories over the phone was that the drug trafficker had new bosses and was recording him for the DEA as he and prosecutors from the SDNY court collected evidence of these crimes.

Valladares’ criminal activity dates back to at least 2008, when he helped Rivera kill a member of his own cartel for violating the rules at a nightclub called Bailables de Occidente in San Pedro Sula. It is facts like these that have been uncovered since 2013, when the small group of DEA agents and prosecutors in New York set out to investigate drug cartels in Central and South America and discovered that Honduras was “one of the world’s main transshipment points for South American cocaine” subsequently consumed in the US.

In short, what US investigators found was that, since at least 2003, “multiple drug trafficking organizations operating in Honduras worked in conjunction with politicians, law enforcement officials, and military personnel” to move mountains of cocaine into the country on planes and boats from Venezuela and Colombia, then on to Guatemala and Mexico for its final destination, the United States. Politicians involved included presidents and congressmen, who received bribes from the cartels, often disguised as ‘campaign contributions’ and, in return, promised policies that allowed the drug trade to continue. Some businessmen were also central figures in this network, for example, to launder illicit money into licit businesses and banks.

The SDNY court investigators also saw that the drug traffickers’ relationship with the state sometimes went beyond bribery. In some cases, cartel representatives were on the state payroll. Narcos had access to information on national anti-narcotics radar systems and naval intelligence, and had the power to divert the attention of the judicial system elsewhere. “These extensive drug trafficking networks contributed to Honduras becoming one of the most violent places in the world,” the SDNY court concluded.

But a key piece of that entire structure was the police, like Valladares. Drug trafficking in Honduras would not have been able to function without the National Police, both at the national leadership level and at the middle management level, as well as the police officers who patrol the streets. Officers received bribes in exchange for information about who the government was investigating, how to avoid military and police checkpoints along their routes, and when and where interdictions would occur. Sometimes the officers also provided security for the shipments as they passed through the country. For example, police officers in the service of Los Cachiros escorted trucks carrying large quantities of cocaine owned by Mexican drug traffickers who were shipping their product to the United States, the SDNY court noted. The officers also played other roles, such as contract killings and money laundering.

Indeed, while US federal prosecutors identified Valladares as the “most culpable” of the officers they had prosecuted as of 2018, his crimes were not exceptional. The court has charged seven Honduran police officers to date, and their investigations and trials are ongoing. The most recent defendant charged was Juan Carlos ‘El Tigre’ Bonilla. The information that has come to light through these cases makes it clear that, in a variety of corrupt ways, the Honduran police institution stopped protecting its people – if it ever did – to serve and protect the drug trafficking business.

DOWNLOAD THE FULL DOCUMENT HERE

The New York Trials

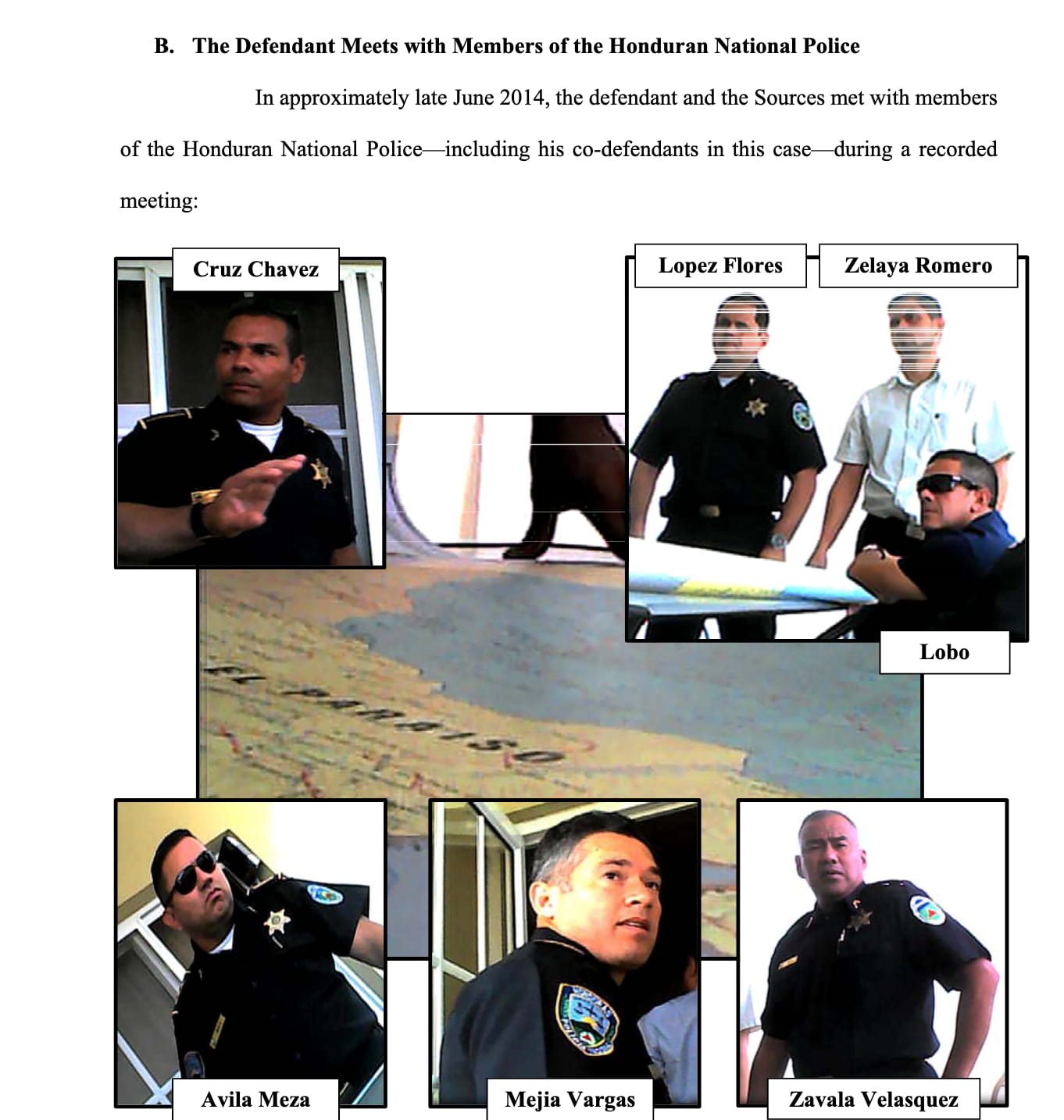

In addition to Valladares, the SDNY court tried police officers Ludwig Criss Zelaya Romero, Mario Guillermo Mejia Vargas, Juan Manuel Avila Meza, Carlos Jose Zavala Velásquez and Victor Oswaldo Lopez Flores. With the exception of Bonilla, whose trial has not yet begun and who has pleaded not guilty, all of the others were found guilty.

According to an interview with a source close to the investigations, the cases that have labeled Honduras as a narco-state began about 8 years ago between the SDNY court team and the DEA. “The goal of our office is to target the highest level of corruption and drug trafficking anywhere in the world” said the source, who asked that their identity be protected so as not to prejudice the ongoing investigations.

The leaders of the cartel ‘Los Cachiros’ were the main ones under investigation but by turning themselves in they gave up a lot of information that was key to the rest of the cases. “That was a big step for our investigation. They had immense information and cooperated fully with us,” he said, adding that although they already thought there was political and military involvement in drug trafficking, “it turned out to be greater than we thought. It crossed party borders, it crossed administrations for more than 20 years, and it wasn’t just that they [drug trafficking] was allowed to pass, but that high-level politicians, businessmen, the police and the army were directly involved.”

But the turning point that gave way for corruption to take over the state was the coup d’état Honduras experienced in 2009.

“The key turning point in the end of any facsimile of democracy in Honduras was the coup,” said Fulton Armstrong, who, between 2008 and 2011, was on the Latin America staff of the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee and, prior to that, served as the U.S. National Intelligence Officer for Latin America. Armstrong was the highest-ranking CIA analyst on Latin America in the U.S. government.

“It was then [in 2009] that the right wing realized that there was now an opportunity to regain control, including control of the police,” said Armstrong, specifying that at that time “the alliance between the Honduran right wing and the right wing in the U.S. Congress and in Washington” was re-established.

Several years before the coup, narco-corruption had already taken root within the police institution. In 2004, the same year that Valladares first accepted a bribe from the Cachiros, another officer, Juan Manuel Avila Meza, began working for the drug cartel. This police officer was also a lawyer, holding regional command posts throughout the country and legal defense positions in several private companies.

According to his case documents, Avila Meza was introduced to Javier Maradiaga by Ruben Santos, a former police officer linked to the criminal network. While at first he primarily used his knowledge as a police officer to help move cocaine and to offer Los Cachiros access to the large quantities of drugs that police had seized from other traffickers, within a few years he also began laundering drugs for Los Cachiros. Within a few years, he also began laundering drug profits and helping Los Cachiros avoid confiscation of money and property from the illicit business, for example, by involving middlemen in the laundering chain and putting a luxury house in San Pedro Sula in his name to prevent the Honduran government from seizing it. He received at least $20 million from for the protection of his assets.

2004 was the year when a third officer, Ludwig Cris Zelaya Romero, was contacted by Fabio Lobo – the son of former President Porfirio Lobo – and Los Cachiros who sought him out on the recommendation of another police officer who was not named in the court documents. The drug traffickers asked him to provide security for shipments from both groups, to which Zelaya Romero agreed. That same year, Zelaya Romero was promoted to the position of Inspector in the Honduran police and received a diploma of recognition for his “valuable participation in the ‘Safer Community’ campaign, demonstrating ability and enthusiasm for the benefit of society.” Shortly thereafter, Zelaya Romero expanded his initial role to coordinate police protection of the transport of Lobo and Los Cachiros shipments through Honduras on their way north. For that service, according to the SDNY court, Zelaya Romero was paid $100,000.

In 2005, another police officer, Mario Guillermo Mejia Vargas, was in monthly contact with Los Cachiros for four years, during which time the brothers alerted him when their shipments would arrive and, along with Zelaya Romero, Mejia coordinated the police officers who would provide armed security for each shipment while guiding the drug traffickers on how to avoid state checkpoints along the route. At the time, Honduras was governed by Ricardo Maduro of the National Party, who came to power promising to be tough on crime. His government gave special prominence to the National Police.

Corruption also ensnared Carlos Jose Zavala Velásquez, a police officer who had held multiple high-level roles in the institution, including with Interpol, the FBI, and with Israeli and US special forces in special operations, among other positions, most of which were focused on police intelligence and combating organized crime. In 2008, when Zavala was named Division Chief of the specialized ‘Cobras’ unit in San Pedro Sula, the police director in that area was Juan Carlos ‘El Tigre’ Bonilla. The following year, taking advantage of his position, Zavala began to guide the trafficking routes of a narco-network led by Hector Emilio Fernandez Rosa, known as ‘Don H’.

‘Don H’ maintained his business for a decade and was responsible for ordering the murder of 19 people, as well as working with Joaquin ‘El Chapo’ Guzman’s representatives to move Mexican drugs north and paying million-dollar bribes to political candidates and state security officials to keep the illicit trade flowing.

Two years before entering the underworld to collaborate with the likes of ‘Don H,’ Zavala Velásquez’s assistant was murdered, so Zavala decided to flee Honduras and seek asylum in the United States. He returned to Honduras in 2008 and was given a position in the “Cobras” police unit. While working for ‘Don H’s’ network, Zavala Velásquez provided security for his shipments for at least three years, receiving between five and 20,000 dollars per shipment, and leaked information to the narcos about possible police checkpoints along their planned routes. He himself accompanied at least one shipment to provide armed security.

In 2009, Mejia Vargas was arrested and jailed in Honduras along with nearly a dozen other officers for participating in an illegal raid on the home of an alleged drug trafficker, but was subsequently released.

According to evidence in the hands of the SDNY court, by 2013, Avila Meza was already laundering money for Los Cachiros through an exotic animal zoo and a front company called INRIMAR, for which he contacted other lawyers to hire their services. He also began collecting debts for Los Cachiros. In early 2014, Zavala Velásquez met Avila Meza and Mejia Vargas at a police academy training in Tegucigalpa, and the latter recruited Zavala Velásquez to provide security for a shipment. In February of that year, Avila Meza led a meeting with “los Cachiros” and the former president’s brother, Antonio Hernandez, as well as Mejia Vargas and another police officer, Victor Oswaldo Lopez Flores, in which he presented maps to the group, identifying checkpoints and offering advice on logistics to improve the operation’s chances of success.

In June 2014, another group of police, including Zavala Velásquez – who, at the time, was an officer in charge of combating organized crime – held a meeting with Fabio Lobo and men they believed to be representatives of a drug cartel but who were actually DEA informants and to whom they offered help with a drug shipment in exchange for a $100,000 bribe. The meeting was recorded and what Zavala Velásquez and his companions did was the same as the meeting a few months earlier between police and narcos: they placed a map of Honduras on a table and described to Lobo and the alleged narcos the Honduran police presence along the cocaine transport routes. In exchange for their support in the operation, in addition to the bribe, they requested new phones, vehicles and a $200,000 pool to bribe other officers. Two years later, Zavala Velásquez was promoted to a position in the Xatruch special forces unit in the Bajo Aguán region, a joint unit with the Armed Forces to address the agrarian conflict in that area of the country. That same year, Zabala was arrested for his involvement in drug trafficking and Fabio Lobo and Mejia Vargas were extradited to the United States.

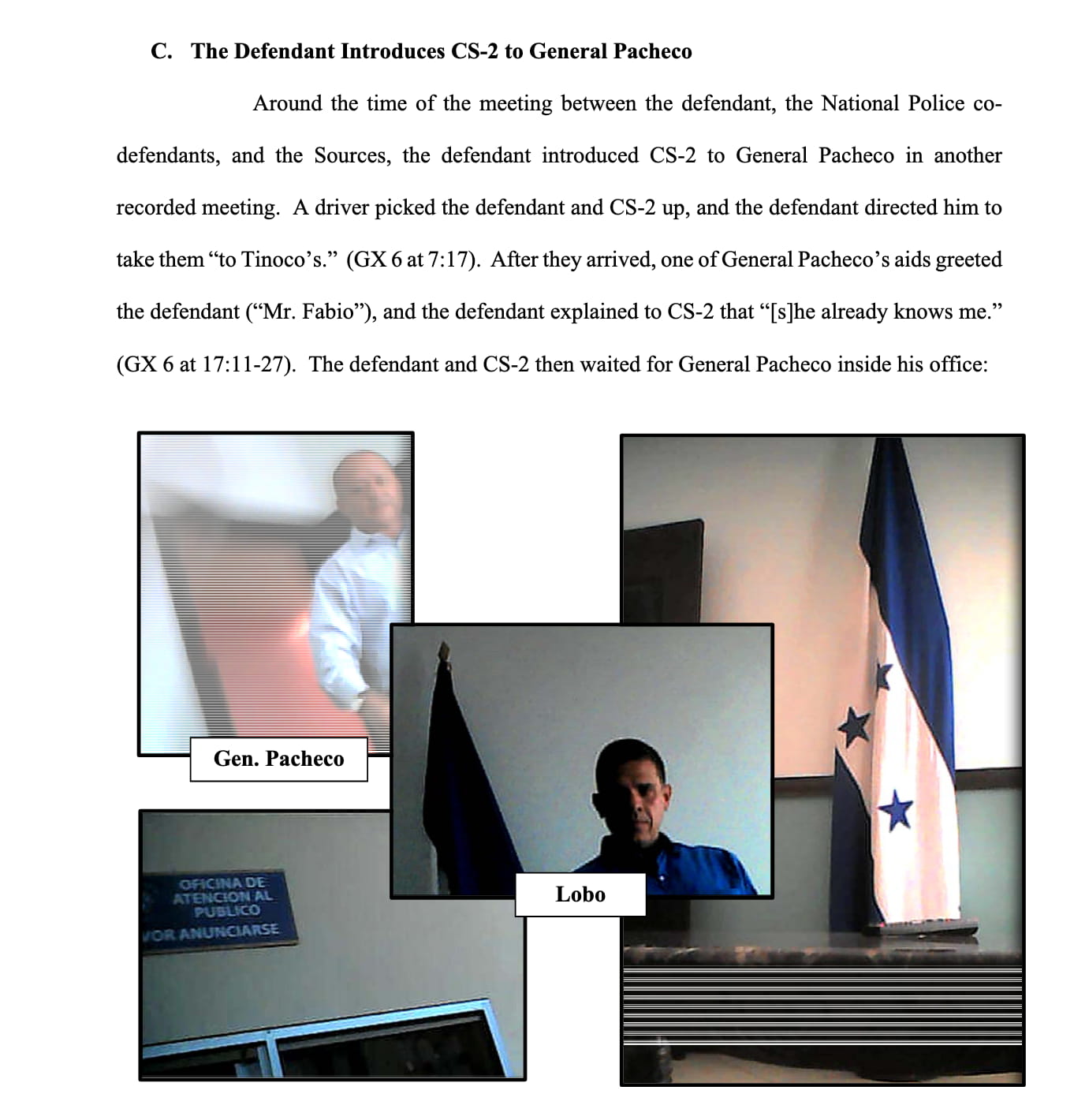

Evidence in the case against Fabio Lobo, at which point he sought support from General Pacheco Tinoco, a military officer and Minister of Security during the government of Juan Orlando Hernández. Pacheco has not been charged so far and he denies links to drug cartels.

U.S. Support for the Honduran National Police

All of this criminal activity by a police force at the service of drug traffickers occurred at a time when the institution was receiving ongoing training from the U.S. government on a variety of topics, such as special operations and counter-narcotics in the jungle and at sea, criminal investigation tactics, community policing, and strengthening the anti-gang unit.

According to a former US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agent who was based in Honduras and who requested anonymity because he was not authorized to speak publicly, the idea behind some US training for state security forces in Central America is to equip elite teams that have undergone a vetting process with the knowledge and equipment needed to tackle crimes such as drug trafficking and stop them before the crimes reach the United States.

With some units, that means not only vetting elected officials through the Leahy Law and a polygraph to certify that they are trustworthy, but also equipping them with materials such as vehicles, uniforms, cell phones and a special office to isolate them from the rest of the police force to minimize the chances that they could divulge confidential information sought by organized crime networks about ongoing investigations, such as the kind of information that was given out by officers on trial in the SDNY courthouse. But, according to the former agent, the road to that goal was always uphill in Honduras. “Even within the unit that had gone through the scrutiny, there were always problems, like constant replacement’; … we had to replace people because of integrity issues.”

Examples of the problems they had included criminal activity, he said, but also minor infractions, such as misuse of official vehicles or work cell phone bills for thousands of dollars of non-work use. What progress the U.S. trainers were able to make in the time they were there was not substantial, the former agent said. The biggest problem was an internal culture of corruption.

“There was corruption from the top down. It was obvious, talking to our unit and hearing their stories and seeing things that could happen. You could hire [a police officer or gang member] to kill someone for five hundred lempiras, that’s how desperate people were for money,” he said, adding that there were many types of corruption at work in the police force but, specifically, “the police were afraid to get in the way of the cartels.”

Honduran Security Minister Ramon Sabillón emphasized that without the support of the United States, a security strategy adequate to the transnational crime problem facing Honduras cannot be developed. He knows this because in his police career he went through two exiles precisely for having dismantled criminal networks. Sabillón said his first exile was to the Dominican Republic with support from the US government in 2006, after he received threats while he was director of the customs police during the Nationalist government of Ricardo Maduro.

“It was because of an issue of arms trafficking, corruption in passports for the entry of citizens from other countries with links to drug trafficking, and the customs issue. I had to take my family out.”

“In the end, I had to leave, they were sending me to a place where they were practically going to turn me in, so I had to go somewhere else, it was a threat against my life”, said the minister.

Sabillón returned in 2009, after the coup, and began investigating Carlos ‘El Negro’ Lobo, a drug trafficker now convicted in the United States. With that case, the minister said he has worked on thirteen cases of extraditable officials. “I collaborated with the DEA, I did my part, but remember that organized crime has several characteristics and that it is systemic, you can be dealing with a person from an institution and it can be a soldier of organized crime. They would warn when we were investigating them, when the system shuts down on you, you can’t do much. But that is changing with the extraditions, we are dealing blows of justice,” he explained and assured that he was never involved in illicit acts despite the fact that he has been previously pointed out as an accomplice of drug trafficker Amilcar Leva Cabrera, ‘El Sentado’ who was killed in 2015 when he was already working as an informant for the DEA.

“El Sentado is dead, the other people are captured, as an investigator one must exhaust all possible avenues, making the appropriate interventions, but there are many people who have been dedicated to lying and discrediting, if he had been linked to him how could he be living peacefully in the United States for six years? He would be in jail there,” Sabillón added.

“The problem is that those who managed drug trafficking were not the police, the police were errand boys, the politicians have managed drug trafficking in this country,” said former commissioner Leandro Osorio. Osorio was purged from the police in 2016, but his case became known internationally because it was he, as director of the Police Investigation Directorate (DPI), who dismantled a drug laboratory linked to Antonio Hernández, brother of the former president, now imprisoned and convicted in the US for drug trafficking crimes.

“If you look, most of the police involved are those who were in the west, there is General Bonilla […] and who sent them were the politicians, but here they [showed society] that the problem in this country was the police,” said Osorio, who has become a recognized analyst on security issues.

About Bonilla, Osorio said that he had a very important relationship with the US government. “If these foreign intelligence units have had important knowledge, I wonder if Bonilla was part of this structure or if they sent him to do a job.”

“Tigre Bonilla had a godson who was one of the Valle Valle,” said Osorio.

“In this country General Bonilla was all powerful in the police, he handled intelligence, he handled prevention, he handled investigation, he handled everything, but what I can say is that at no time in my case did he ever give me an arbitrary order,” Osorio continued.

“On the contrary, I did an operation against an officer in the southern zone who was meeting with some criminals, among them some drug traffickers, and I immediately relieved them of their duties,” he said.

There is no doubt that successive US presidential administrations have empowered corruption networks in Honduras. Armstrong, the former intelligence analyst, said the culpability of the United States for continuing to support Honduran administrations after the coup – which were clearly corrupt – is enormous. “We have been the enablers, the facilitators, the ones who gave the green light to the coup plotters, to Lobo and JOH. This includes some major Democrats and the evidence was there for a long time,” he said.

According to John Lindsay-Poland, a researcher working for the American Friends Service Committee, an organization affiliated with the Religious Society of Friends (the Quakers), “the Biden Administration has not substantially changed most foreign policy objectives in the region. Nor have they sanctioned U.S. forces involved in training foreign forces involved in serious crimes,” as required by the Leahy Law, adding that “thus there is no paradigm shift.”

Lindsay-Poland, who for decades has been a writer on U.S. foreign policies toward Latin America, said the United States must take responsibility for having supported such regimes and their corrupt security forces. “But right now, that’s an imaginary world,” he said.

Meanwhile, in Honduras, Osorio called the purification commission a “narco-commission” because he agrees with current police authorities that the purge only served to annihilate the police.

In February 2022, Osorio told Honduran media that 85% of all purged police officers would return to the National Police because the claims against the State are in the millions. He, for his part, said that he does not plan to return to the institution.

“Perhaps 10% of those purged were those who were linked to crime,” said Osorio.

But the powers of the state were managed poorly, he explained.

“So, many of us who were removed were removed because we were a hindrance to the drug trafficker Juan Orlando Hernández Alvarado.”

Osorio said it has been frustrating how entrenched crime in the state has challenged the security forces. The commissioner recounted that after arresting people linked to the former president in 2015, that same year, in December, he realized that one of the detainees was released “on leave” on December 31 from prison.

“They paid more than ten million to an army officer who was the director of a penal center for that individual to go to his New Year’s Eve dinner at the house.”

“[I] recaptured him again in a clinic in San Pedro Sula and sent him to prison.”

Osorio said that when he reported the capture to one of the government ministers, he sensed the minister was annoyed.

The person Osorio had recaptured “subsequently escaped from the prison, his whereabouts are still unknown,” and the record was lost from the prison.

For Osorio, there is currently a reconfiguration of organized crime and he mentioned several signs and causes of this, one of them, he said, is the capture and extradition of Juan Orlando Hernández Alvarado, another is the escape of the leader of the Mara Salvatrucha MS-13, ‘El Porkys,’ and also the sentencing of Carlos Alberto Alvarez Cruz, alias ‘Cholo Houston,’ another leader of the criminal organization. He also explained that “there is also the zero-tolerance policy, of the Salvadorean President, Nayib Bukele, thus there is a natural reason that pushes these [criminal] organizations to Honduras and Guatemala, they are coming even in boats”.

El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele has established a seven-month state of emergency following a failed negotiation his government held with the Mara Salvatrucha. Osorio denied that Bukele has negotiated with gangs, despite evidence of this, and advised that the new government of Xiomara Castro in Honduras should take as an example what its neighbor is doing. “I think this government should look to at El Salvador as they were in front of a mirror,” he said.

Meanwhile, Deputy Commissioner Muñoz expects reinforcements in Trujillo, a municipality that has seen a spike in violence that has even directly touched its police. Between January and June 2022, the Trujillo police reported 39 homicides and 4 undetermined violent deaths, a high figure considering that, during the whole of 2021, the police reported 37 homicides and 6 undetermined violent deaths, to these figures were added the three police officers killed in April.

Muñoz showed us the bulletholed car parked in front of his police office and told us “the boy [the driver who was a young policeman?] was saved by a miracle; that happens when God has a purpose and it is not your turn to die.”

“I’m going to ask them to move this car from here because people look at it and get scared.”

THIS REPORT WAS SUPPORTED BY A GRANT FROM THE FUND FOR INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM.