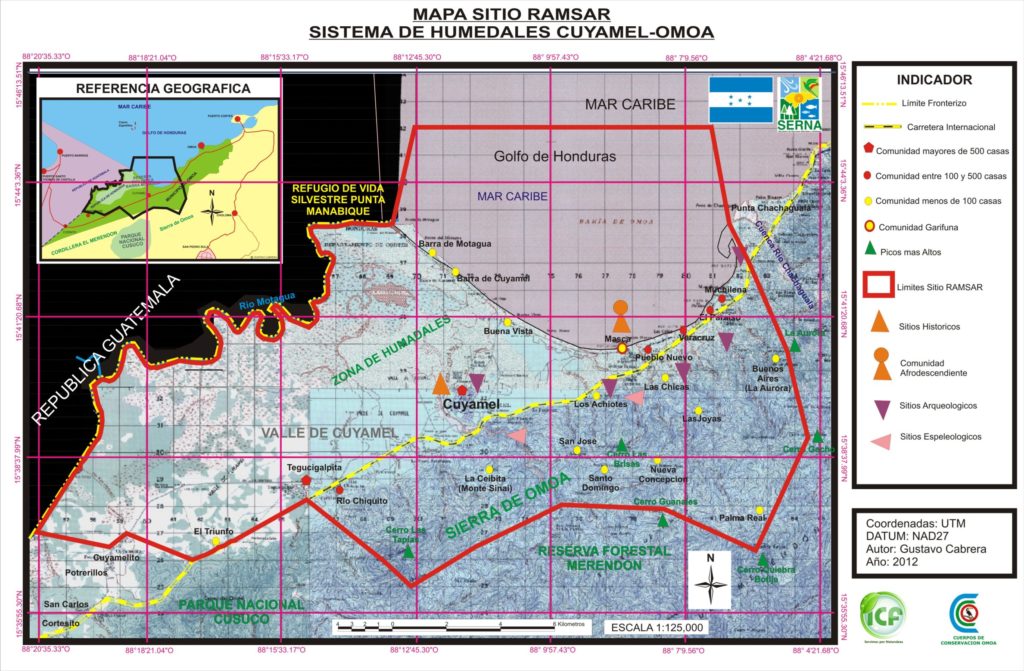

In the coastal border area between Honduras and Guatemala lies the land once slated for the Cuyamel-Omoa National Park (El Parque Nacional Cuyamel-Omoa - PANACO). In 2011, Honduran environmental authorities, with information and support from different NGOs, proposed that a protected area be created there. The wetlands of the region belong to the second most important coral reef barrier in the world: the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System. Indeed, the biodiversity of this area and its ecosystem services are so important that, in 2013, Omoa was declared a site of international importance no. 2133 by the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands (making the region a ‘Ramsar site’). It is now dying in the face of the advance of oil palm and king grass monocultures, under the complacent gaze of Honduran environmental authorities.

Text: Areli Palomo Contreras

Colectivo Linea 84 Periodismo Etnográfico y Acción Comunitaria

Photographies: Fernando Destephen/ Contracorriente

Investigation: Arelí Palomo Contreras y Roberto Chávez

Editiing: Jennifer Ávila / Contracorriente

The land where PANACO was to be located is currently inundated by oil palm and king grass, and the file corresponding to the declaration of the protected site was burned in a fire in the offices of the Forest Conservation Institute (Instituto de Conservación Forestal, ICF), which originally designated the area for protection.

PANACO was ended in the name of benefiting business people claiming to be producers of clean energy. The cost is the disappearance of a site that could have been a very important water reserve for the country.

The flood zones of what would have become PANACO, located in the municipality of Omoa, include two mighty rivers that flow down from the mountains and bathe the plains on their way to the coast. One is the Cuyamel River that descends from the Sierra de Omoa; the other is the Motagua River, the natural border between Honduras and Guatemala, an area that also suffers from garbage contamination that adds to the deterioration of the wetlands.

Omoa is a remote place, the daily life of its 77 communities blending with the lush vegetation. 24 of these communities depend mainly on fishing, agriculture and tourism.

According to the journalist alliance Tras las huellas de la palma (on the trail of the palm) there has been no investigation by state entities of the installation of oil palm plantations in these important wetlands.

The alliance built a database of 298 records of fines and sanctions, issued between 2010 and 2021, against 170 companies and individuals linked to the palm oil business in six of the main producing countries in the region – Colombia, Honduras, Guatemala, Ecuador, Brazil and Costa Rica. In the case of Honduras, six requests for information were made to the authorities, but in 12 years only three cases were identified and none were related to Omoa and its wetlands.

The protected area that never was

We arrived at Cuyamel, in Omoa, to talk to Gustavo Cabrera, a short man with short black hair. He says that many pass through here asking about the communities that are sinking in the Caribbean due to the rising sea, a visible effect of climate change in this area. They also ask him about the waste carried by the Motagua River that contaminates marine and terrestrial life.

Cabrera, a native of Omoa and son of farmers, says he grew up with the conviction of loving his people and his forest. He is a biologist and one of the founding members of the non-governmental organization, Conservation Bodies of Omoa, (Cuerpos de Conservación de Omoa CCO), created in 2001 with the idea of establishing a protected area in the municipality: PANACO.

Cabrera says that they had to make many efforts. In their favor was the fact that the area’s ecosystems are part of the Mesoamerican Reef System (MAR). In 2006, as part of the NGO Alianza TRIGOH (Tri-national Alliance for the Gulf of Honduras), CCO sought to establish a binational biological corridor that would link the Punta Manabique protected area in Guatemala with the protected area they wanted to propose in Omoa. In the same year, the 1997 Mesoamerican Caribbean Reef Systems Initiative was ratified, committing the MAR “custodian” countries (Belize, Guatemala, Mexico, and Honduras) to make institutional and financial efforts to care for the reef.

Everything was lined up to create PANACO. <<Still, it was not possible, there was no will. The authorities were not interested>> says Cabrera.

Efforts from the NGO that Cabrera helped found continued in the following years until, within the same framework of the MAR initiative, the European Commission appeared on the scene with the Sustainable Management of Natural Resources and Watersheds of the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor in the Honduran Atlantic project. Cabrera says that in this scramble for funds, the Omoa Conservation Corps organization managed to include the park’s proposal in the project and finally obtained resources to carry out a biophysical diagnosis of the area in 2010. They were able to integrate the necessary information so that the Forest Conservation Institute (ICF) could finally propose the official declaration of PANACO to the National Congress.

On June 28, 2011, the declaration of PANACO was published in the congressional gazette, La Gaceta, and it explained the Honduran State, through the ICF, had announced its decision to declare the park a protected area through Ministerial Agreement 008-2011. This resolution legally delimited and protected 30,031 hectares of marine and terrestrial areas. This agreement was the basis for subsequently declaring the entire PANACO area as a Ramsar site in 2013. Only one step remained for the park to become a reality: for Congress to make the official declaration.

For Cabrera’s organization, this was a triumph. The park’s 2012-2024 Management Plan was immediately created. The document stated that the core zone had to be set aside for conservation.

The file for the declaration of PANACO was sent on September 4, 2011, to Rigoberto Chang Castillo, the Secretary General of the National Congress at the time.

Twenty days later, Chang had submitted the PANACO bill to Congress, waiting for the president of the legislative chamber at the time, Juan Orlando Hernández – who is now facing trial in the United States on drug trafficking charges – to approve and sign it. According to requests for access to information made for this investigation, those are the latest communications on the status of the PANACO proposal in the National Congress archives.

And it turns out that the file disappeared.

A copy of the file was requested from the ICF. Their response was: “This Department does not have such information, given that the file that was in the custody of the DAP [Department of Protected Areas of the ICF], was burned during the fire that occurred in the ICF facilities on April 26, 2013, which was communicated to the public through Agreement 01A-ICF-2013 and published in La Gaceta No. 33,122 dated May 13, 2013.” Further, “the file submitted to the National Congress of the Republic was lost in said State Body”.

The PANACO proposal remained in legal limbo and was never declared by the National Congress. Due to its regional and international importance, its boundaries and geographic area of 30,031 hectares coincide almost entirely with the hectares declared as a Ramsar site in 2013.

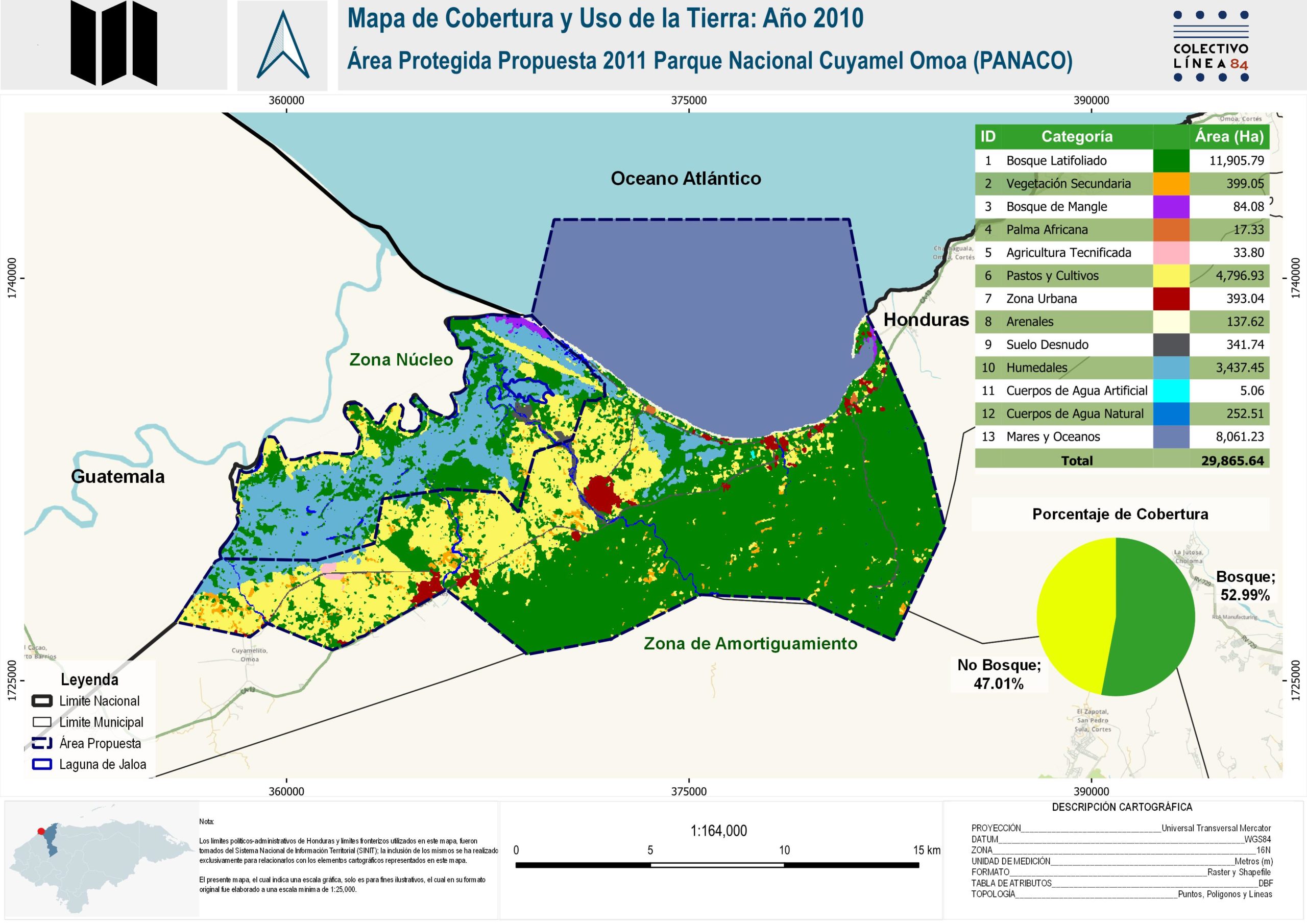

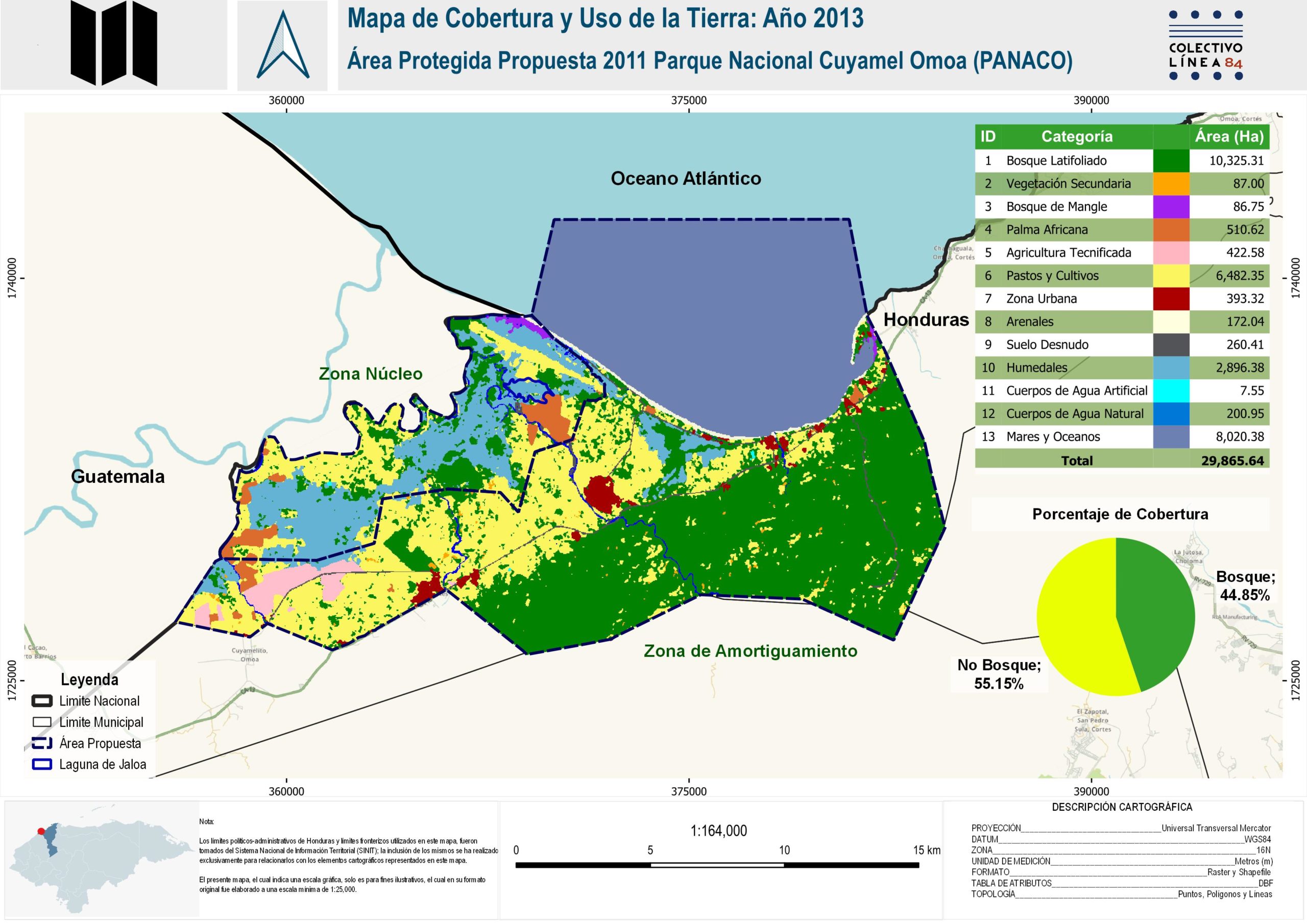

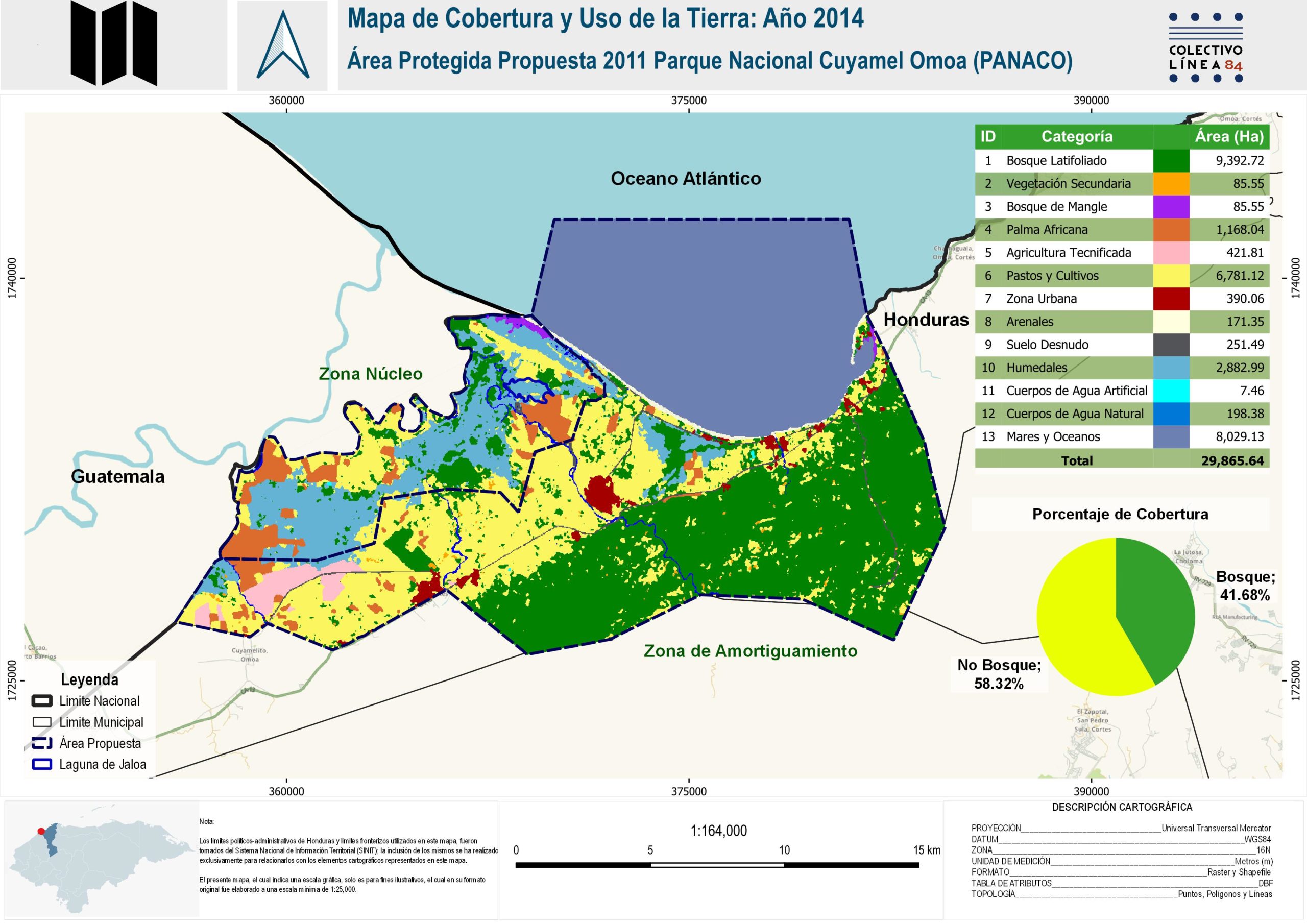

Between 2011 and 2014, the Cuyamel wetlands, located in the core zone intended to be protected by PANACO, were destroyed. About 1,170 hectares of wetland disappeared.

The destruction of the Cuyamel wetlands

<<I arrived here in 2018 when a large part of the wetlands of what would become PANACO had already died>> says an Omoa resident. Locals talk about the old protected area proposal and whisper about what caused its demise. Not everyone dares to mention the details because, they say, behind it are the great economic interests of <<powerful people>> overseeing the monoculture of oil palm and king grass (also known as grass, or elephant grass).

The disaster, they say, began with the palm plantations. The palm growers arrived in this area of Omoa around 2012. Locals remember how they used large tractors to uproot the trees “with roots and all” to prepare the land. They also dug to make canals and divert the course of the Cuyamel River. “If you could see how all that was! Now that the [Jaloa] lagoon is almost lost, you won’t see it like before, there’s nothing left,” says Ezequiel (a pseudonym to protect his identity), as we walk towards the Jaloa Lagoon.

Gustavo Cabrera corroborates what Ezequiel says and assures us that the palm growers altered the dynamics of the wetland to the point of disaster.

According to PANACO’s management plan, the Jaloa Lagoon and its surroundings were the heart of the wetland.

The Cuyamel wetlands began to be destroyed shortly after ICF made the proposal for the declaration of PANACO. By 2012, the Association of Co-Managers of Protected Areas in Honduras (Asociación Mesa de Organizaciones Comanejadoras de Áreas Protegidas de Honduras MOCAPH) publicly denounced the deforestation of the site and presented a report of damages to the wetlands. The press also reported it. In 2013, Alianza TRIGOH issued a statement warning about the destruction of the areas that would become part of the Cuyamel-Omoa park, and the Mangrove Network also urged about the illegal logging of the mangroves in Ramsar site 2133. All urged the environmental authorities to act and stop the advance of the palm in the area.

On November 4, 2013, the Cooperativa Mixta Palmas del Caribe (COMPACAL Ltd), the only company dedicated to palm cultivation in the region, applied for an environmental license to plant oil palm on a total of 2000 hectares. Their project is located in what was the core and buffer zone of the former proposed protected area in Omoa and within the current Ramsar site.

COMPACAL Ltd. was established on August 18, 2012. It has 25 members, including Guillermo Noriega Suárez and his daughter Gilma Edelmira Noriega González.

Guillermo Noriega is known in Honduras as the Timber Magnate. In 2005, the U.S. Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) detailed Noriega and his daughter Gilma’s timber operations. The report on illegal logging mentions the dismissal of Gustavo Morales, former director of COHDEFOR (formerly ICF) in 2004, in connection with the indiscriminate granting of logging permits in the department of Olancho to Comercial Maderera Noriega. The businessman’s daughter told EIA undercover agents that the basis of this business was the payment of government officials and her closeness to one of the country’s major political figures: former Honduran President Porfirio Lobo Sosa.

Over time, Noriega’s business diversified. <<Don Guillermo did not have palm at that time, I think that is a new investment of his (…) He is a lumber dealer, that has been, he has been dedicated to the lumber business, he was in the area of Olancho and that has been his main activity, I did not know that he had planted palm…>> says former president Lobo Sosa in an interview with the journalistic alliance.

<<Noriega is not one of the big palm growers>>Lobo says and then calls him on the phone. According to Lobo, Noriega assured him that he indeed had about 200 manzanas (approximately 140 hectares) of oil palm, but that he currently had about 50 manzanas left because the sand had buried the rest, mainly because, in 2020, COMPACAL suffered losses due to the floods that hurricanes Eta and Iota caused in the area.

Tras las Huellas de la Palma has tried persistently to contact COMPACAL’s representatives, but no response has been obtained to date.

Expanding palm

By September 2013, months before COMPACAL applied for its environmental license,

Redmanglar had already issued an urgent communiqué alerting the authorities, both MiAmbiente and ICF, about how palm growers and other agrofuel-producing entrepreneurs were destroying the wetlands of the Ramsar site. In October of that same year, the Asociación Mesa de Organizaciones Comanejadoras de Áreas Protegidas de Honduras (MOCHAP) issued a communiqué stating that the authorities had endorsed the destruction of 800 hectares of the site in favor of agro-industrial oil palm projects.

After the company’s environmental license application in 2013, the Environmental Evaluation and Control Department (DECA) of MiAmbiente convened the National Environmental Impact Assessment System (SINEIA) – a group of people including technicians, authorities and civil society – which has the task of making an inspection of the site, preparing a report and then a technical opinion to see whether or not the license is granted.

In COMPACAL’s technical report No. 66/2014 of January 13, 2014, it insists that the project is already operating and the ICF needs to verify where the plantations are located – to see if they coincide with the protected area or special or fragile ecosystems – and to determine if the palm plantation can be done in the area.

The file was sent to the head of ICF’s Protected Areas and Wildlife Department, Alejandra Reyes, who asked the Institute’s Northwestern Region to visit the area. In the technical report APNO-01-2014, biologist Alex Vallejo, coordinator of Protected Areas in that region, declared that oil palm planting was viable.

This document was used by Reyes to endorse the palm project as technically viable in the area that ICF itself had proposed in 2011 as Cuyamel-Omoa National Park.

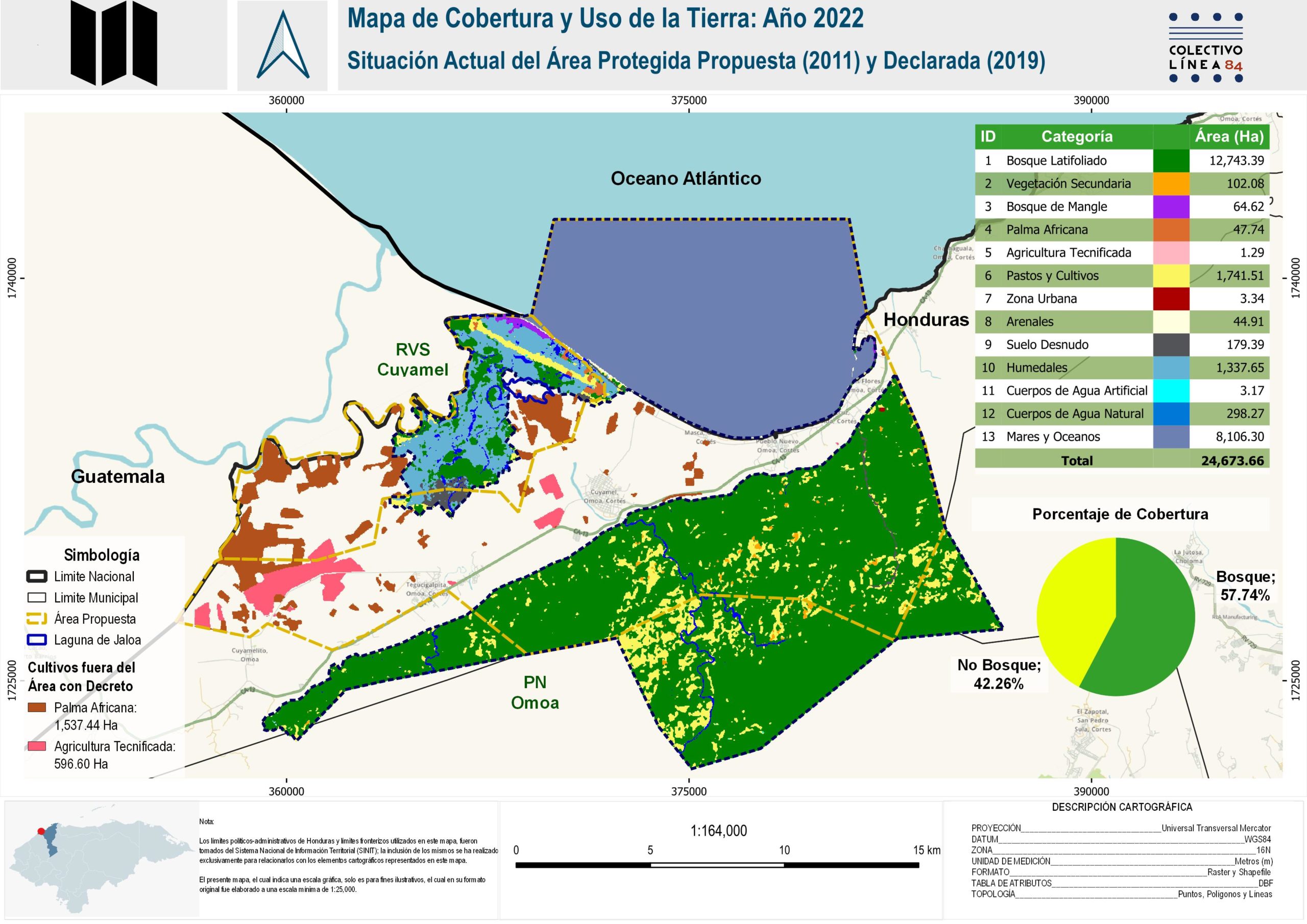

In his opinion, Vallejo never reported the damage that had already been caused previously to the wetlands, considering that by 2013 at least 510.62 hectares of palm were already planted in the heart of the wetland, as seen in this map made from satellite images for this investigation.

In 2014, several contradictions began to appear among various Honduran environmental authorities. Alejandra Reyes requested the opinion of the Wildlife Department (DVS) of the ICF to judge, this time, whether a project to plant king grass could be carried out in the area. It also requested the opinion of the General Department of Biodiversity (DiBio) of MiAmbiente regarding the site, since it is a Ramsar site, and asked it to find a company for having planted the grass without a license.

However, in the DAP-008-2014 ruling of the palm company COMPACAL, Reyes did not request the pronouncement of ICF’s Wildlife Department, nor MiAmbiente’s guidelines regarding the Conventions that safeguard the Ramsar site.

ICF only asked MiAmbiente to fine the palm company for starting operations without authorization. The amount of the fine was 5,000 lempiras, the equivalent of only US$200.

Although MiAmbiente ended up sanctioning COMPACAL, the entity did not mention this case nor did it provide information about it when this journalistic alliance requested, through information requests, the details of the sanctioning processes against palm oil companies.

On February 10, 2014, the Department of Environmental Assessment and Control (DECA) of MiAmbiente, with the approval of the ICF, issued its technical opinion No. 200/2014 in which it asked COMPACAL – in order to move forward with the licensing process – to conduct an Environmental Audit Study (EAA), given that the plantation had already begun and was a category 4 project, that is, it is part of the projects considered of greater risk to the environment for containing irreversible damage and of great magnitude, according to the environmental categorization table of that time. The document mentions contamination from the use of agrochemicals in soil, air, water, flora, and fauna.

A direct source from MiAmbiente with several years of experience in environmental license procedures, and who asked for his name to be withheld, explains in an interview that the “punishment” for starting activities without a license “is nothing… it is 5000 Lempiras regardless of the category [of the project], 1, 2, 3 or 4…”.

“Although PANACO was an area still in projection, it had already been subjected to the various biological characterization studies, for which the ICF declared its viability as a protected area and as a RAMSAR site [which was declared in 2013], which implies that the authorities were already aware of its importance at the local, regional and international level,” comments the expert source.

Despite all this, on July 16, 2014, the Minister of MiAmbiente, José Antonio Galdames Fuentes, in Resolution No.0871-2014 granted COMPACAL a Provisional Environmental Certificate and indicated that, within six months, it had to present a report on compliance with all the measures imposed on it and leave a guarantee fund of 15 million 500 thousand Lempiras (approximately US$622 thousand) to be spent in the event of non-compliance with the measures and/or environmental damage that was not remedied in time. In addition, he informed the company that it would have to pay a fine of US$200 for having started oil palm cultivation without a license.

Days later, on July 28, 2014, COMPACAL’s legal representative, Rebeca Lizeth Melara Raquel, asked MiAmbiente that instead of submitting the compliance report every six months, it could do so every year. In addition, she asked for the return of the guarantee fund money because the basis for calculating the amount was not for the entire project, corresponding to 2,000 hectares, but for 698.8 hectares of inspected crops that were approved in the provisional environmental certificate.

The truth is that, by 2014, in what was to be PANACO, there were already 1,168 hectares of oil palm.

In 2015, MiAmbiente gave in to the company’s requests and ended up charging COMPACAL only 1,480,000 lempiras (approximately US$60,000) for its guarantee fund.

The moment it all ended

On July 16, 2015, ICF and Jesús Juan Canahuati Canahuati, owner of the company HGPC Agrícola, which grows king grass in the wetlands that were to be protected by PANACO, signed a Cooperation Agreement to recategorize and redefine the protected area. Among the company’s obligations and responsibilities would be “to provide technical and financial support for the process of redefining and declaring the Cuyamel-Omoa area”.

By the end of 2015, there was not much to do. The wetlands were already full of palm and HGPC Agrícola would start planting king grass in one of its farms, after the re-delimitation of the area. PANACO was dying.

By September 7, 2016, PANACO was officially dead.

With full financial support from HGPC Agricola, PANACO was recategorized and its boundaries were redefined. A new biophysical diagnosis was made and another file was created. On that date, the new protected area proposal was published in the official gazette La Gaceta by ICF Executive Decree No. 0392.

The new area would be called the Cuyamel-Omoa Subsystem of Protected Areas (SAPCO) and would be divided into Omoa National Park and Cuyamel Wildlife Refuge. Jaloa Lagoon would remain outside of the protected area.

Three years later, on September 18, 2019, through legislative agreement No. 101-2019, the National Congress of Honduras issued the official declaration of SAPCO, achieved with the support of HGPC Agrícola.

This journalistic alliance tried insistently to contact HGPC Agrícola for comment on their role in the delimitation of PANACO and how this benefited their king grass plantations. We have not received a response to date.

Although there are mitigation measures and requirements for planting African palm and king grass, most of Cuyamel’s wetlands no longer exist, and those that remain are severely reduced and damaged.

The Jaloa Lagoon, the representative of the heart of Cuyamel’s wetlands, was left at the mercy of the surrounding palm plantations and is not incorporated into the new protected areas. The PANACO file disappeared from the archives of the National Congress and the ICF. No one explains how it happened.

What remains

“There’s not much left,” says Ezequiel as we walk between palm plantations and pasture. We are looking for the Jaloa Lagoon; the heart of what used to be the wetland. As we walk, I remember what a local environmental activist said: “Here we survive on fishing and the little tourism that comes in… with the pesticides they use on the palm trees, the fish are dying. The lagoons have dried up and the people have nowhere to fish. The resources are running out.”

What used to be PANACO and the Cuyamel wetlands are filled with palm and grass.

We finally reached the Jaloa Lagoon, our steps sinking in its swampy soils. We got on a cayuco (boat) and rode a small stretch of what was left. The palm plantations became the clandestine tombs of the Omoa wetlands and much of its vegetation. The marks that delimited the old core zone of the park are still in the area: they are like natural tombstones that remind us of what used to live there.