Journalists in Honduras are vulnerable to violence, and impunity is the norm after any are attacked, threatened, or murdered. The only body in Honduras that investigates violence against journalists is the FEPRODDHH (a special prosecutor office). However, it only has five courts, all in Tegucigalpa and no dedicated investigators or any legal right to investigate murders.

Text: Leonardo Aguilar

Photos: Jorge Cabrera y Fernando Destephen

This article was edited in collaboration with the LatAm Journalism Review (LJR)

Honduran cameraperson and TV presenter Ricardo Ávila told his boss that he lost control of his WhatsApp account; something he saw as a possible hacking of his phone.

A week later, on May 26, this year, he was killed with a shot to the head while driving to work in Choluteca, in the southern part of the country.

After this violent act, 93 journalists and media workers have been killed in Honduras since 2001.

In astatement released on May 24, the National Human Rights Commissioner (CONADEH) said that impunity in the murders of journalists exceeds 91%. Likewise, it explained that between 2016 and April 2022, the Internal Forced Displacement Unit (UDFI) received around 67 cases of journalists (20 women and 47 men). Of those, 51 are at risk of displacement and at least 16 have already been victims of forced internal displacement, due, in 81% of cases, to threats, followed by attempted murder, extortion, injuries and family violence.

“Of these more than 90 murders, the rate of criminal investigation is very low. We only have four cases where there is a sentence for the crimes of homicide or murder; and approximately 22% of them are under investigation. The other cases are subject to total impunity, and we assume that they will remain that way because 15 to 20 years have passed,” Osman Reyes, president of the Association of Journalists of Honduras (CPH), told Contracorriente.

The only office that exists in the country to investigative violence against journalists and protect them is theSpecial Prosecutor for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders, Journalists, Communicators and Justice Workers (FEPRODDHH), but it has only five prosecutors – all based in Tegucigalpa – without assigned investigators and without legal jurisdiction to investigate murders.

How do the mechanism for protection and the special prosecutor for journalists operate in Honduras?

Honduras has the Protection System for Human Rights Defenders, Journalists, Social Communicators, and Justice Operators, which came into effect in 2015 and, as of November 2021, recorded 126 active cases.

This protection mechanism is called to work in coordination with the CONADEH and with the public prosecutor.

Both the CPH and the Honduran Bar Association (CAH) withdrew from the protection mechanism in 2021 as a form of protest, alleging passivity of the protective space.

“We have this protection mechanism for journalists, lawyers, people from vulnerable groups, but it is not acting in response to these complex situations,” Reyes said.

However, since 2018, Honduras has also had the Special Prosecutor (FEPRODDHH), but its presence is not visible.

Despite the fact that Reyes is the president of the CPH, he said that he has not heard anything about the FEPRODDHH for two years and that he does not even know who the head of said prosecutor’s office is.

“I understand that at the time, this special prosecutor’s office was created to deal with these cases. We were in contact two years ago with Prosecutor Keila Aguirre, who had create a team and with them, we allocated some cases, but she contacted me one morning and told me that they had already rotated her out of the prosecutor’s office. To this day I don’t know who remained, I don’t know if that prosecutor’s office still exists, if it continues to work, because at least in my capacity as president of the Association of Journalists I never had contact with that prosecutor’s office again,” Reyes said.

Reyes added that he met with Security Minister Ramón Sabillón in 2022, but that he was presented with the same data and advances given by previous governments.

“We had meetings with three security ministers from three different governments, the same presentation made by the first was made by the second and the number of advances is the same as that of the third. The classic answer is always: we are investigating and going nowhere,” Reyes said.

Amada Ponce, director of the Committee for Freedom of Expression (C-Libre), a coalition of journalists and civil society organizations, agrees with Reyes and said that C-Libre’s experience with FEPRODDHH is unsatisfactory because the majority of the cases don’t receive the necessary attention.

“As of last year, there were only two prosecutors assigned,” she told LJR.

“The majority of cases that we have filed with these prosecutors have not been attended to in the more than three years that we began to file claims. One of the most difficult experiences to deal with has been with the cases that have been brought from media workers and human rights defenders who are in the territories, where the human and investigative resources are very limited,” Ponce said.

Vulnerable group | Complaints since 2018 | Complainants | Prevalence of crimes reported | Departments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Journalists | 64 complaints as of May 14, 2021 | 12 women and 52 men | Threats, disclosure of secrets, injuries and damages, limitation and impediment to fundamental rights, abuse of authority, violation of the duties of officials, torture, violation of freedom of expression, theft, discrimination, crimes against intellectual property. | Francisco Morazán, Choluteca, El Paraíso, Colón, Yoro, Cortés, Atlántida, La Paz, Santa Bárbara, Comayagua, Valle, Copán, Intibucá. |

Human rights activists | 136 complaints as of May 16, 2022 | 51 women and 85 men | Illegal detention, threats and homicide, kidnapping, hate speech, threats, coercion, home invasion, injuries and damages, abuse of authority, violation of the duties of officials, torture, raid by public officials and employees, discrimination, employment discrimination, sexual harassment. | Francisco Morazán, Copán, Yoro, Cortés, Colón, La Paz, Santa Bárbara, Choluteca, Valle, Atlántida. |

Judicial operators | 52 complaints as of May 13, 2022 | 31 women and 21 men | Attack, intimidation of witnesses and others, threats, coercion, abuse of authority and torture, cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment, abuse of authority, violation of the duties of officials. | Islas de la Bahía, El Paraíso, Francisco Morazán, Cortés, Choluteca, Ocotepeque, La Paz, Olancho. |

Table prepared in June 2022 by Contracorriente with data provided by the public prosecutor’s office through the Institute for Access to Public Information.

Ponce said that FEPRODDHH does not have access to the photographic voter registry of the National Register of Persons (RNP) to identify the aggressors against these vulnerable groups.

“This prosecutor does not have access and we thought that was a big deal. We are talking about identification of an aggressor, a task that does not represent any effort or expense. Access to a photographic registry only means a password and entering that registry. Other prosecutors have it, but this one does not.”

Ponce said that they have presented more than 300 complaints before the public prosecutor, but “to date, none of the cases has been concluded with a final sentence, not that we know of.”

Complaints made by journalists, lawyers, and human rights activists to the FEPRODDHH | |

| 2018 | 61 denuncias |

| 2019 | 97 denuncias |

| 2020 | 39 denuncias |

| 2021 | 33 denuncias |

| 2022 | 12 denuncias |

*The FEPRODDHH didn’t include complaints made to other organizations. | |

Figures compiled by Contracorriente in June, 2022 por Contracorriente using data provided by the Public Ministry through the Institute for Access to Public Information

“This gives us the feeling that this prosecutor’s office was created in name only, and not to bring aggressors against vulnerable groups to justice,” Ponce said.

No cases being tried

Contracorriente found out that 252 complaints have been formally filed with FEPRODDHH since the creation of the prosecutor’s office in 2018.

Prosecutor Jerry Vallardes, head of FEPRODDHH, told Contracorriente that there haven’t been any sentences passed yet, and that currently there are no pending cases against aggressors against journalists, or human rights defenders being tried in courts or criminal tribunals. Vallardes only mentioned that there is a case that could possibly go to oral and public hearing, but that involves a judicial operator.

To understand why the cases with FEPRODDHH do not advance, or why sentences that generate precedents to protect journalists are not obtained, Valladares explained that many of the cases are referred to a justice of the peace, where they are settled by way of conciliation, while other cases known by FEPRODDHH are referred to other prosecutors, such as those for ethnic groups or crimes against life.

In the hearings of the justice of the peace courts, the victims are exposed to and face their attackers, who in many cases can be police or military personnel.

According to Amada Ponce with C-Libre, most of the attacks against journalists are committed by police and military.

“This is common in a country like Honduras, which is very weak in terms of human rights and access to democracy,” she said.

Since the 2009 coup d’état, protests in the country against the deterioration of institutionality and the displacement of vulnerable populations from their territories have been on going. The protests persist today despite the fact that the new government represents a large part of what was the political and social opposition. In this environment of continuous protests, the repression by the police and military has been constant and journalists and activists have been among the most affected.

“Most of the cases we have are cases of threats and personal injury. However, in accordance with the Code of Criminal Procedure, although these are crimes of public action, consequently, a particular instance is required, that is, that the victim authorizes us or gives their consent to initiate the investigation and to be able to prosecute the case in accordance with Article 26 of the Code of Criminal Procedure,” Valladares said.

Regarding how they get cases, Vallardes said that, “In most cases, the complaints come through organizations or through the protection mechanism.”

The chief prosecutor of FEPRODDHH said that the cases, that are not remitted to a justice of the peace, on most occasions fade away because the victims “unfortunately” don’t trust the judicial operators.

One of the ways in which the FEPRODDHH turns the case over to another prosecutor’s office, Valladares said, is based on the “causal link,” meaning, they assess whether the aggression against the journalist occurred due to the exercise of their work or if it happened because of a personal issue. If they cannot confirm that a journalist has been attacked or threatened because of their work, they pass the case on to another prosecutor’s office.

Vallardes does not see any problem with the fact that FEPRODDHH does not have jurisdiction to handle cases of murders of journalists, because in his opinion, “The issue of crimes against life is a fairly complex issue. Even having information centralized to be able to clarify criminal structures, criminal conduct, relationships with firearms, relationships between people is complicated. Then it was determined that all crimes against life be investigated by the Prosecutor for Crimes Against Life, there are deaths against women, politicians, journalists, vulnerable groups,” he said.

“Currently, we only have an office in Tegucigalpa and we have jurisdiction and scope to hear cases throughout the country. Regarding the logistics issue, we have the necessary support, the vehicles to make the journeys, and support with travel expenses. We have not had limitations to the budget to cover emergencies in San Pedro Sula, La Ceiba, Choluteca, but I think that the Achilles’ heel is that we do not have investigators,” Valladares explained.

He added that the FEPRODDHH only has five prosecutors, including himself, and all of them are in Tegucigalpa, with only the ability to try some crimes related to the “limitation of fundamental rights,” meaning, threats, injuries, and others.

In the absence of investigators, these five prosecutors also have to act as investigators.

“That void is filled with the same prosecutors, who become investigators, when we need to go, we go,” explained Valladares, who said that “by function of scope,” ATIC (the investigative arm of the public prosecutor’s office) only deals with crimes of high impact, crimes of corruption, organized crime, homicides, and murders, “so we are limited in being able to work cases with the ATIC,” he said.

Valladares said that his office does not have the technical knowledge to be able to identify the origin of cyberattacks.

“The real situation in the country is complex because, let us remember that social media like Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, and WhatsApp, operate freely in the country, but there are no representatives of all these companies in the country. All their representatives are based in the U.S., so when we require information from these companies it is impossible to access this information and especially with this type of crime,” he said.

Osman Reyes, CPH president, said he’s concerned about the situation of journalists in Honduras.

“We are in a complex situation as a profession. Regardng the case of Ricardo Ávila, a cameraperson for one of the largest channels in the south of the country, we must also add the threats faced by journalist Manuel Santiago Serna, a veteran journalist in the city of San Pedro Sula who is being harassed by phone, messages – from numbers registered in Colombia, they have even sent him private photographs of his own family,” he said.

Reyes said that similar threats, with numbers registered abroad, have been received by the former president of the CPH, Dagoberto Rodríguez; “We can say that we are at a critical moment, that far from improving, far from getting out of a critical situation, we see that it tends to worsen.”

A murder in southern Honduras

At the beginning of the investigation into the murder of 25-year-old Ávila, police said it was a traffic accident. Then they put forth the hypothesis that it was a robbery. Now, after evidence has emerged, they said it was a murder.

Amada Ponce said that MetroTV, the channel where Ávila worked, was one of the few channels that covers social movements in Choluteca.

Over the last three years, C-Libre has issued a total of 11 alerts about threats and harassment that journalists from MetroTV in Choluteca have received.

A week before his murder, Ávila notified the owners of MetroTV that he lost control of his WhatsApp account, which was internally interpreted as a threat.

Alejandro Aguilar, owner and manager of MetroTV, told Contracorriente that he gave instructions to the staff to block Ávila’s number.

“We didn’t know who was using his WhatsApp. But we never imagined what would happen a week later. We did not imagine the tragedy,” he explained.

Although Aguilar said that he didn’t know the reasons why Ávila was killed, he is interested in obtaining protection measures both for himself and for the employees at his channel.

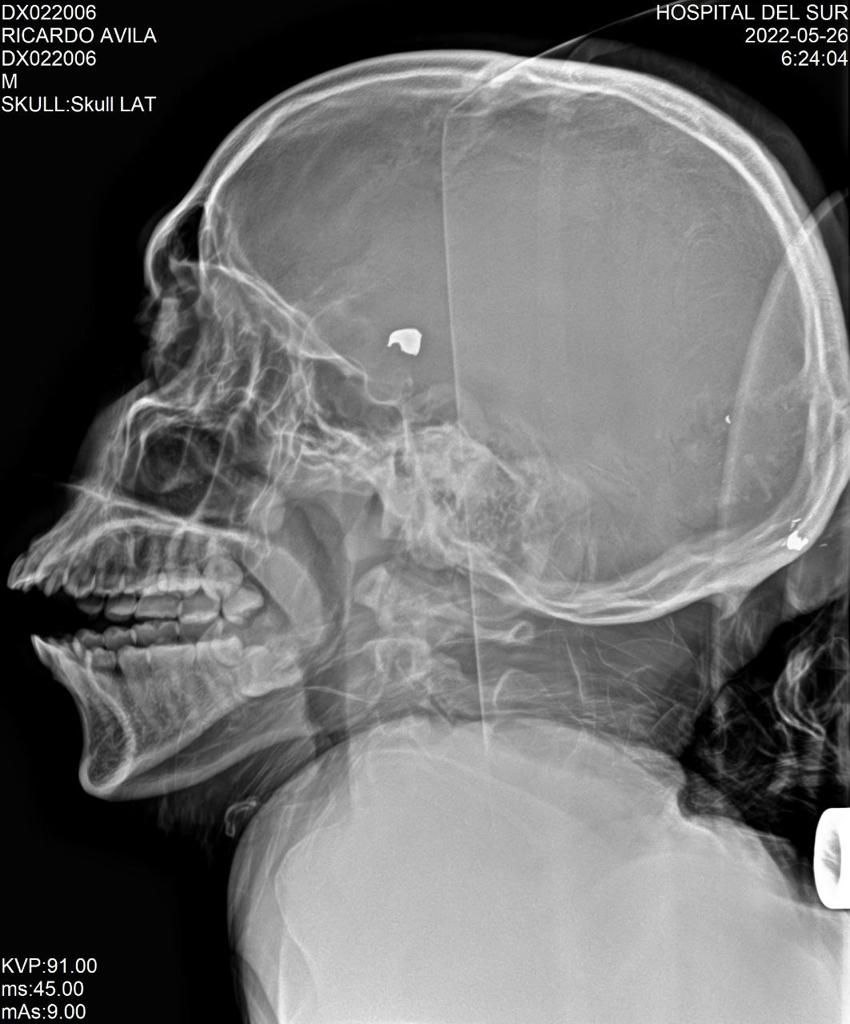

Aguilar said that in the hospital in southern Choluteca, at first it wasn’t clear that Ávila had been shot in the head. Then, the X-rays came, “When the person in charge of X-rays arrives, he looks at me and asks, ‘Has Ricardo ever been shot?’ And I tell him no. And he tells me: ‘Come on, look at the pictures.’ You could see the bullet entrance in one part of his head, and a bullet inside, in his brain. So the staff became worried.”

While the doctor and the person in charge of the X-rays tried to understand what happened with Ávila, Aguilar took the time to make a pair of phone calls.

“I called a man who is in charge of the patronage of a community close to where they said that the alleged accident occurred. I woke him and asked for help, ‘They tell me that Ricardo had an accident, but I need you to go to see, because they said that the motorbike is still on the edge of the street. Help me, if it’s possible, pick it up and then tell me. When you arrive, I need you to find the helmet and take a picture of it.’ The man later called me and told me, ‘I just got here and the motorbike is being taken by the police.’ I said to the man, ‘Ask them to give you the helmet.’ He sent me the photos of the helmet and there you can see the bullet hole.”

Aguilar showed the images of the helmet to the surgeon, who, surprised, told him that it matched the X-rays. “‘It was a shot,’ the surgeon told me,” he remembered.

Later, Ávila was transferred to the Teaching Hospital of Tegucigalpa, the capital of Honduras, where he died on May 29.

Contracorriente contacted the spokesperson of the National Police in the department of Choluteca, Officer Gerson Escalante, who said no one has been captured but they have identified “suspects” that caused Ávila’s murder.

“The investigations regarding the journalist continue, everything points to those suspects belonging to a criminal group from Marcovia,” Escalante said.

The version provided by Escalante to Contracorriente was that the patrol from the National Police received a 911 call reporting a road accident with a motorcycle.

“Then in South Hospital, it was observed that the person had a wound caused by a firearm without an exit wound. Then the National Police went to where the injured person was found to carry out an examination of shell casings and to carry out investigations there. Information was collected on who the suspects were and to start there were two hypotheses,” Escalante said.

Escalante affirmed that the first hypothesis was about a robbery. “It was purported to be an attempted robbery, but according to investigations, that is being ruled out.”

The police spokesperson added, “It was a targeted attack. The goal was to end his life. So far, I do not have the information on what the reason was for these criminals to have taken his life, this data is managed by the DPI (Police Directorate of Investigations).”

“There are two teams investigating this murder. There is a team from Choluteca and a team from Tegucigalpa investigating,” explained Escalante, who added that violence has increased in Choluteca in recent months.

¿Qué dice la ministra de Derechos Humanos sobre el asesinato de Ricardo Ávila?

Natalie Roque, human rights minister, told Contracorriente that the murders of Ricardo Ávila and a prosecutor in Nacaome, which occurred on May 29 and 27, respectively, added to the threats that some journalists are experiencing, are due to a rearrangement of organized crime in light of the new government.

“Not just the murders, but also the threats show a very strong reaction by organized crime, as they regroup to keep control and use other types of violence,” Roque said.

Prosecutor Karen Almendarez was killed on May 27, a day after the murder of Ricardo Ávila. That also happened in the southern region of the country, specifically in the municipality of Nacaome, Valle department. Almendarez was assigned to the Environmental Prosecutor’s Office.

The human rights minister said that as long as the structural conditions for violence remain and that it is focused on human rights defenders, journalists and judicial operators, there will be no prosecutor’s office capable of putting a stop to the violence.

“It must be recognized that the human rights ministry has the National Protection Mechanism, but this needs a profound restructuring since it has not been a guarantor for the life of this sector of the population either,” the secretary said.

Roque views the actions of prosecutors in different officeswith much concern and said that the levels of impunity are enormous.

“As long as we continue with these problems of impunity and weakness in the investigative processes, we are not going to have guarantees of rights,” she said.

“We have seen the recent threats, murders, and aggressions, against judicial operators, journalists, and human rights activists, and this tells us also that we must redouble, triple and multiply efforts, because the actions of some prosecutors are very limited due to lack of resources. There may be will but if there is no support it is difficult to guarantee rights,” Roque concluded.

Two teams investigate the murder of Ricardo Ávila

Ponce regrets that it is a different prosecutor’s office, such as the one for crimes against life, that handles these type of cases, and that there is no special prosecutor’s office trained to investigate deaths of journalists. Because, in her opinion, it is evident that in the case of Ricardo Ávila there has been bias since the beginning of the investigation.

“The police were insisting, from the beginning, that the murder of Ricardo Ávila was a robbery or common violence, however, we know that absolutely nothing was stolen from the journalist. His backpack, money, his belongings, and cell phone were still on his person and the keys were in the motorcycle. How can they have robbed him if all the things he was carrying were in his possession?,” she asked.

The media outlet where Ricardo Ávila worked had previously made 11 complaints for which C-Libre issued alerts, stating that they felt vulnerable due to the exercise of their journalistic work. During Ávila’s funeral, on Monday, May 30, part of the journalistic union of Tegucigalpa and the southern zone demanded justice for the death of the journalist.

“We call on Hondura authorities to clarify this criminal attack that led to the loss of life of colleague Ricardo Alcides Ávila, with the aim of presenting those responsible before the courts,” C-Libre said in a statement.

This article was edited in collaboration with LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).