Ex-president Juan Orlando Hernández (2014-2022) was arrested at his home in Tegucigalpa and taken to the police special forces headquarters after the United States requested his extradition on drug trafficking charges.

By Leonardo Aguilar, Vienna Herrera, Jennifer Ávila, Fernando Silva, and María Maradiaga

Photos by Jorge Cabrera and Fernando Destephen

After the United States formally requested his extradition, former president Juan Orlando Hernández was arrested on February 15 by a police special forces squad led by the security minister General Ramón Sabillón. Police and military forces had cordoned off Hernández’s residence the day before to prevent his escape.

The arrest came after the United States presented a request to the Honduran Supreme Court for Hernández to be extradited to face three criminal charges.

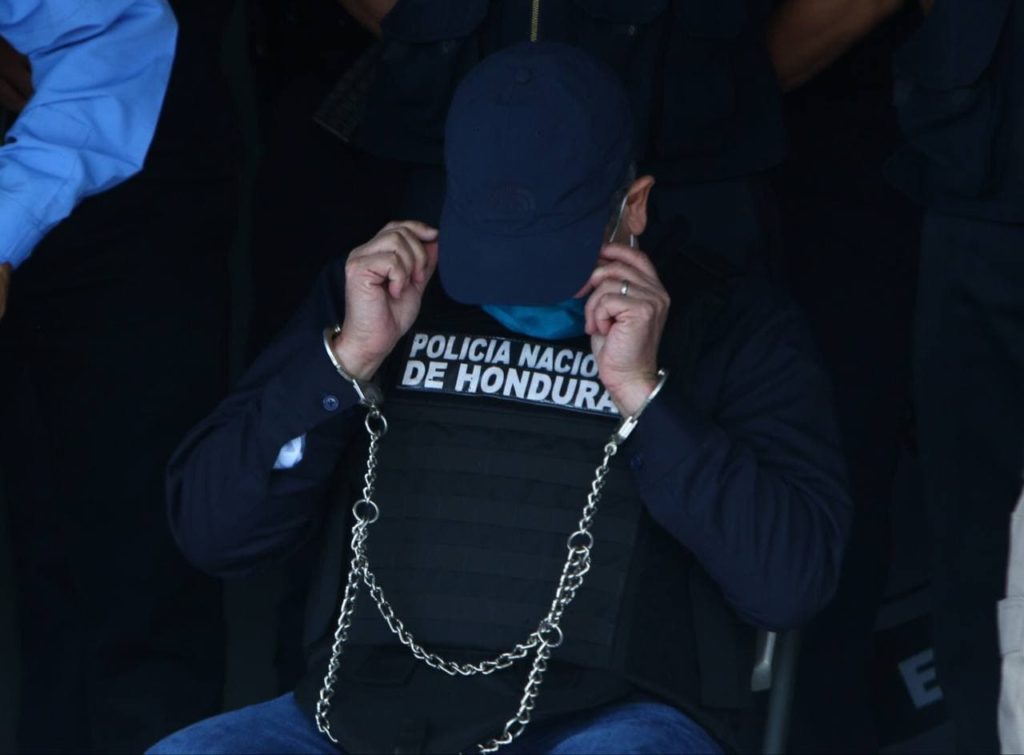

With his hands and feet cuffed, Hernández wore a black cap, a facemask, and a bulletproof vest as he was escorted by police to a van and later taken to the Special Forces Command facilities by helicopter.

The National Police issued a statement declaring that the arrest was carried out by order of President Xiomara Castro, who demanded strict application of the law, and in coordination with the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). The statement affirmed that police protocols were strictly followed in order to ensure the safety of the former president.

Minister of Security Sabillón stated that Hernández would be remanded to the custody of the Special Forces, and would be transferred at 10:00 am on February 16 to the Supreme Count for his first arraignment.

Hernández tweeted an audio message on February 15 stating that he had informed the National Police that he would voluntarily turn himself in once the Supreme Court appointed a judge to hear his case; “It’s 5:45 a.m. This message is for all of you who have supported me with your prayers and good wishes. Thank you very much. It’s not an easy time─ I don’t wish this on anyone. The purpose of this message is to tell you that my representatives have informed the National Police that I am willing and ready to cooperate, and will voluntarily turn myself in when the Supreme Court appoints a judge to hear my case. I am doing this to face the situation head on and defend myself. Greetings to all.”

Sabillón, exiled abroad during the Hernández administration, held a press conference to state that after his arrest, Hernández would appear before the appointed judge to face charges of drug trafficking, arms trafficking and unlawful association. Sabillón assured that the entire process would comply with the law, that the National Police had an established procedure for extradition cases, and that no exceptions would be made in the former president’s case.

“The president has instructed us to act in strict compliance with the law,” said Sabillón.

Honduras and the United States signed a bilateral extradition treaty in January 1909, as well as a supplemental agreement in February 1927. However, since the Honduran constitution did not allow the extradition of its citizens, it was amended in 2012 to allow the extradition of Honduran citizens accused of drug trafficking, money laundering, and terrorism. The constitutional amendment enables the courts to appoint a judge to review documentation and issue arrest warrants pertaining to an extradition of a citizen. A group of magistrates held a plenary session via Zoom on February 15 to appoint a judge, which was confirmed by Supreme Court spokesperson Melvin Duarte.

Read: Former Honduran president Hernandez gains immunity from drug trafficking allegations

Duarte said that the name of the appointed judge had not been divulged in any of the 32 previous extradition cases, but it was leaked that the judge hearing Hernández’s case was Edwin Francisco Ortez Cruz. Since 2014, the Supreme Court has handled 32 extradition cases, said Duarte, and only one case was delayed due to extraordinary circumstances. He stated the process takes approximately four to five months.

Hernández’s legal defense team issued a statement that reiterated the willingness of their client to voluntarily turn himself in, and that he was awaiting the appointment of a judge as required by the constitution and current extradition treaties. The statement indicated that Hernández expected full protection of his human rights, and assurances that his case would proceed in the same manner as the 32 previous extradition cases.

Read: President-elect Xiomara Castro’s inauguration means new hope for Honduras

The statement from the Hernández defense team read, “In accordance with the provisions of the court-approved writ for these cases, the extradition process consists of two hearings. The first is to inform the subject of the extradition request of the charges against him or her. The second hearing is held a month later and consists of the presentation of evidence. After that, the judge considers the case and issues a decision, typically two or three months later. The decision can be appealed.”

A message for Honduran politicians

Hernández’s National Party issued a statement expressing support for the former president, and requested respect for due process and the “respectful treatment of the former president of Honduras” by security forces.

In February 2021, an investigation into the National Party by Insight Crime (published in Spanish by Contracorriente), revealed that the political party that governed Honduras from 2010 to 2022 had become a federation that welcomed politicians and officials involved in criminal businesses ranging from timber to drug trafficking to the misappropriation of public funds.

In recent years, several National Party politicians have been sanctioned by the United States under the Magnitsky Act and named on the Engel List. These laws impose sanctions on human rights violators and corrupt and anti-democratic actors, and deny them visas to enter the United States.

Former congressional representative Oscar Nájera has been sanctioned under the Magnitsky Act and named on the Engel List. A National Party legislator for 30 years, he lost his seat in the November 2021 elections. In an interview with Contracorriente, Nájera said the extradition request for the former president is “a media event more than anything else. The international left’s strategy is to destroy democracy. All this comes from right here in Honduras, from these crooks who live off the NGOs [non-governmental organizations]. They used to always speak up for Juan Orlando and now they don’t even poke their heads out.”

Nájera and Hernández were added to the U.S. State Department’s Engel List of corrupt and anti-democratic actors in Central America at the same time. However, Hernández’s inclusion on the list was kept secret until February 8, 2022, after he left office. Although Nájera has publicly acknowledged that Honduras is indeed a narco-state, he claims to have no knowledge of the allegations against the former Honduran president.

“I support Hernández, but if he was involved in anything irregular, he knows why he did it and will have to suffer the consequences. I feel sorry for him, and especially for his mother and children. Actually, I never knew much about President Hernández. I heard press reports about him, and I consider myself a friend of his brother, but I never could have imagined all this,” he said. Najera was referring to the former president’s brother, Antonio “Tony” Hernández, who was sentenced to life plus 30 years in prison by the Southern District Court of New York for drug and arms trafficking. Najera said that he greatly admired the U.S. justice system because even though he has demanded to be investigated by the U.S., “none of my enemies have been able to destroy me.”

The charges against Hernández

A document leaked from the Honduran foreign ministry to the press with an informal translation of the extradition request sent by the U.S. Embassy specifies the three main charges against Hernández: 1) Conspiracy to import a controlled substance into the United States; manufacture and distribution of a controlled substance; possession of a controlled substance with intent to transport it aboard a U.S. registered aircraft; 2) Using and carrying firearms, or aiding and abetting the carrying and possession of firearms including machine guns; and 3) Conspiracy to use or carry firearms including machine guns and destructive devices during and in connection with the importation of narcotics.

The leaked document states that from 2004 to 2022, Hernández participated in the trafficking of approximately 500,000 kilograms of cocaine to the U.S., transported to Honduras by air and sea from Colombia, Venezuela and elsewhere; “Hernández received millions of dollars in bribes and profits from multiple drug trafficking organizations in Honduras, Mexico and elsewhere. In return Hernández protected drug traffickers from investigation, arrest and extradition.” The document also accuses Hernández of using Honduran police and military forces in these drug trafficking activities and allowing brutal acts of violence to be committed.

Another allegation in the leaked document is that in 2005, when Hernández was seeking reelection as a National Party legislator, he accepted US$40,000 from a drug trafficker named Victor Hugo Diaz Morales (alias “El Rojo”) through his brother, convicted drug trafficker Juan Antonio “Tony” Hernández. “El Rojo” was a witness for the prosecution in Tony Hernández’s trial.

In 2009, Hernández allegedly received US$100,000 from “El Rojo” for his campaign to become president of the National Congress. In exchange, Hernández fed him information on anti-drug security operations. The document alleges that “El Rojo” and Hernández transported 140,000 kilograms of cocaine to the U.S. during that period, and that in exchange for US$2 million, Hernández worked with former president Porfirio Lobo Sosa in 2009 to help extradited drug trafficker and former mayor of El Paraíso (Copán), Amílcar Alexander Ardón Soriano. Lobo and Hernández also allegedly promised government jobs to Ardón and his cousin, protection from arrest, and contracts for fictitious companies controlled by drug traffickers to launder money.

Hernández is also alleged to have accepted US$1 million for his 2013 presidential campaign from drug trafficker Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán in exchange for protecting the Sinaloa Cartel’s activities in Honduras. Hernández ordered Ardón to bribe certain politicians and election officials and to go to several municipalities that didn’t support Hernández in order to manipulate the vote count and ensure his victory in the 2013 elections.

During his first term as president, Hernández made a deal with Geovanny Fuentes Ramirez who gave him US$25,000 in exchange for protection and information on security operations. Hernández told Fuentes that he wanted access to a cocaine laboratory near a major Honduran port, and allowed Fuentes access to military personnel for his personal use.

In 2017, Hernández solicited Ardón’s support for his campaign for a second presidential term. Ardón used approximately US$1.5 million in drug money to bribe election officials and politicians, and Hernández was unconstitutionally re-elected to the presidency.

Hernández continued to collaborate with drug traffickers in Honduras while his brother was on trial in the United States. The leaked document states that on or around May 29, 2019, Fuentes visited Hernández at his home and agreed to pay bribes in exchange for protection. Approximately one week after Tony Hernández’s conviction, prisoners armed with machetes and guns murdered Magdaleno Meza (“co-conspirator 2”) in a Honduran prison to prevent him from testifying against the ex-president.

In an interview with Contracorriente, former president Porfirio Lobo commented on the allegations in the extradition request leaked by the Foreign Ministry, saying that while he never had a personal friendship with Hernández, his interactions with him in the political arena never revealed anything suspicious like drug trafficking. Lobo also denies any dealings with other implicated politicians such as former mayor Alexander Ardón.

“This allegation that I was involved with Ardón of El Paraíso is false. I have never been in any meetings with him─ never. I have nothing to do with him,” said Lobo.

He claims he never did anything during his presidency to protect drug traffickers, but this is not the first time his name has surfaced in allegations of illegal activities. On October 11, 2019, Devis Leonel Maradiaga Rivera, the former head of the Los Cachiros cartel, testified at Tony Hernández’s trial that he paid between US$500,000 and US$600,000 to Lobo in exchange for protection from extradition. In 2016, Lobo’s son, Fabio, pleaded guilty in the Southern District Court of New York to knowingly and intentionally conspiring to import cocaine to the United States.

In July 2021, Lobo was added to the Engel List and named in the Pandora Papers investigation (led by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and conducted in Honduras by Contracorriente and the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística – CLIP)). This far-reaching investigation found that Lobo owned three shell companies in Panama while he was president. His wife managed another offshore company while she was first lady, and Lobo’s son and right-hand man also sought to create companies in tax havens.

Regarding the possibility that the next extradition request will have his name on it, Lobo claims to be unafraid, and says that he’s willing to turn himself in voluntarily if that happens.

“I’m not afraid of anything. I don’t owe anything, and when allegations first surfaced in 2017, I went to the Attorney General and asked to be investigated. I told the U.S. Embassy that I was here if they needed me. My lawyer at the time even went to the U.S., and it’s not easy to get appointments there … When the Engels List was published, which is just a copy and paste of the MACCIH (Mission to Support the Fight Against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras) investigations, I went back to the Attorney General and asked again to be investigated, like I’ve done since 2017. If they summon me, I’ll go. But I can guarantee that I’ll return,” said Lobo.

Juan Orlando Hernández didn’t act alone

The cases brought by the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York clearly reveal that Honduras has become a narco-state whose government institutions promote and permit large-scale drug trafficking. These institutions include the National Police and the Armed Forces, which were supposed to be leading the battle against drug trafficking. Now, less than a month after the inauguration of a new president, these same institutions were ordered to immediately arrest former president Juan Orlando Hernández.

A large contingent of special forces, transit, preventive and border police units was deployed to the residence where the former president was staying in Tegucigalpa. The first security forces to arrive at the Hernández residence were from the Military Police, a unit that Hernández created and unsuccessfully tried to formally establish in the constitution. They were gradually withdrawn until they were more than 200 meters from the residence. Sabillón led the operation and waited for the court order that would allow him to personally arrest the former president, backed by an institution that faces the enormous challenge of cleaning itself up.

Alfredo Landaverde, a former leader of Honduras’ fight against drug trafficking, was the first to provide the facts that would reveal the country to be a narco-state, and his warnings resound loudly today. Landaverde was assassinated in 2011 for these allegations. His widow, Hilda Caldera, spoke to Contracorriente on the historic occasion of Hernández’s arrest. She said that there were too many people implicated in the case, “It’s a very large-scale case, so support from abroad, from the United States, is clearly needed because many people with power and influence in this country are implicated.”

“The blood of martyrs calls for justice. My husband was the first to stand against this. He saw what was happening, and these are the types of events that honor his memory. He faced this alone, sacrificing himself, and challenging the powerful drug traffickers,” said Caldera.

“I don’t want to kick Mr. Hernández’s family when they’re down, but if you look at all the deaths, all the victims of drug trafficking, all the people who consume drugs, this is unforgivable. Alfredo once told me, ‘Drug trafficking cannot be forgiven because it affects young people the most.’ It’s a never-ending cycle of suffering, and I’m just one of the many victims,” she said.

Hilda Caldera says it’s important to bring down the entire network around Juan Orlando Hernández; “He was at the top, he had the most power. That means there was a very large network that we definitely hope will be dismantled. We need to reveal the whole web that he set up.”

Josué Murillo, an attorney and international political analyst, told Contracorriente that the requested extradition of Hernández should not be surprising because U.S. Representative Norma Torres had already publicly called for it. “Once he stepped down from the presidency, Hernández was vulnerable to both domestic and international justice proceedings. Besides the public disclosure of his wrongdoing, we are hoping for justice to be imparted in accordance with legal due process. The Honduran and U.S. people who have been affected by the deeds and misdeeds of Juan Orlando Hernández deserve this and now he must pay the piper,” he said.

Murillo thinks that Hernández’s network will also be brought to justice; “The close political and personal friends around Juan Orlando Hernández will be scrutinized by the U.S. justice system and also by the Honduran people. We know that he did not act alone. The almost total impunity he enjoyed while he governed the country was aided and abetted by several figures in his cabinet and in the country’s security forces. I believe that they will also be investigated in due course and will be brought to justice if there is sufficient evidence.”

Juan Orlando Hernández became a member of the Central American Parliament (Parlamento Centroamericano – PARLACEN) immediately after leaving office. The PARLACEN provides diplomatic immunity for its members, but the experts consulted by Contracorriente concur that this immunity doesn’t necessarily protect him from extradition.