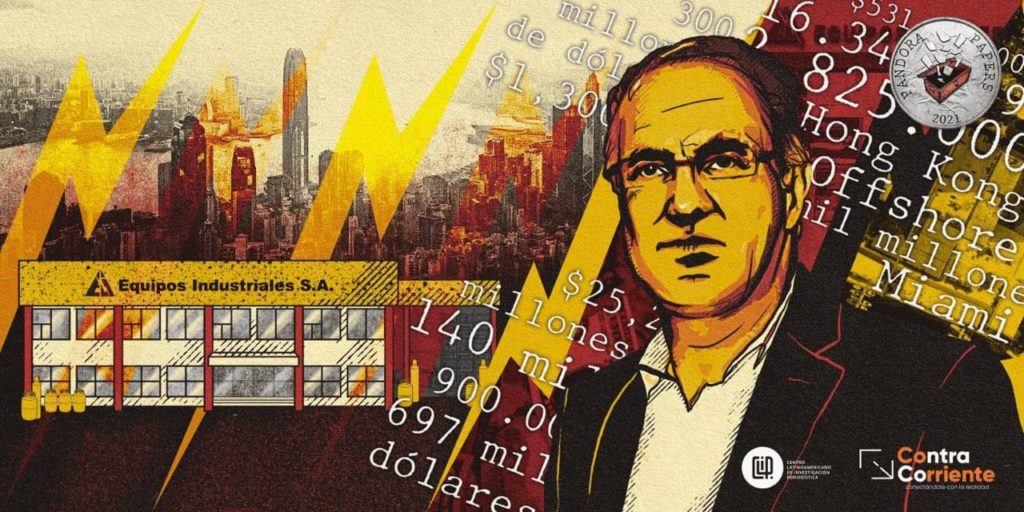

After selling equipment to Social Security for three times its value, according to the Attorney General’s Office, businessperson Fauzi Rishmawy created multiple companies in tax havens. Equipos Industriales, Rishmawy’s Honduran company, continues to be a state contractor and is one of the suppliers of the Honduran Energy Company (EEH), which manages the bills and distribution of energy in the country.

By Jennifer Avila, Andrés Bermúdez Liévano y María Teresa Ronderos y *

Ilustrations: Miguel Méndez

Photos: Martín Cálix/ Tercer Piso/ Contracorriente

“Great works are not done with force, but with perseverance,” said Pastor René Peñalba at the inauguration of the new and modern facilities of the electrical materials company Equipos Industriales S.A. in San Pedro Sula, Honduras, on September 30th, 2013. According to photos published on the social pages of Honduran news outlets, much of the country’s industrial elite attended the ceremony, including engineer Fauzi Salomón Rishmawy Hode, who had founded the company 24 years earlier, his wife and co-founder, Julia Cristina Suárez, and their sons, Juan José and Alejandro Rishmawy, also partners with their father in other companies.

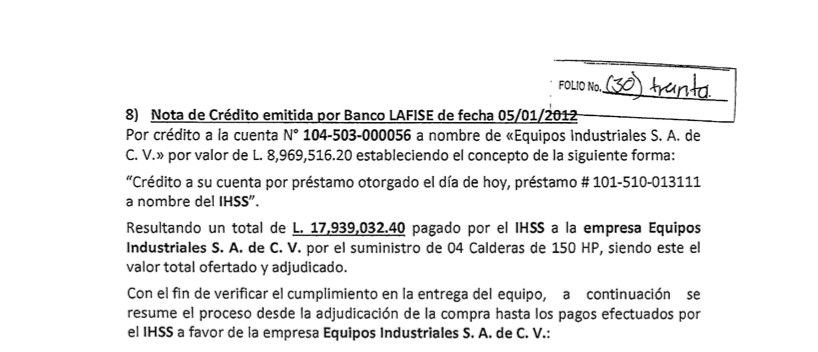

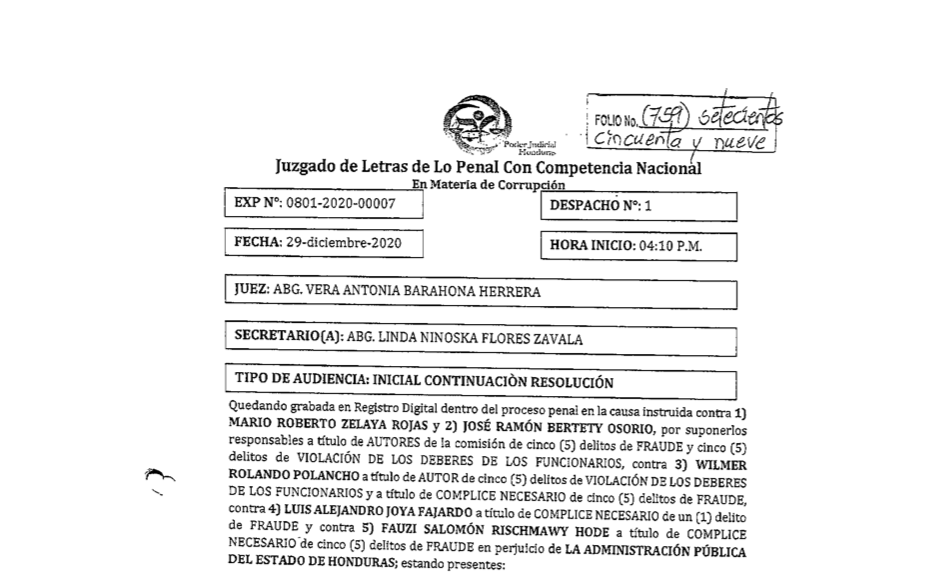

However, a case opened by Honduran courts in 2020 shows that the success of Equipos Industriales was not only due to perseverance. In July 2011, the company supplied hospital equipment to the Honduran Social Security Institute (IHSS) through a direct award contract, which, according to the Honduran Attorney General’s Office, had irregularities, including inviting bidding under unequal conditions, approving purchases without appropriating the corresponding budget, and advances of 50% instead of 20% as required by law.

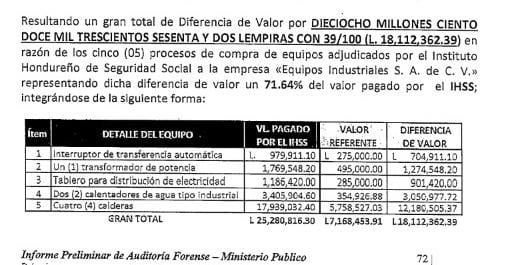

The IHSS paid approximately US$1.3 million for the equipment and, according to the Public Ministry calculation, Rishmawy Hode’s company pocketed a margin of 18.1 million lempiras (equivalent to about US$945,000 at the time). In other words, if the institute had purchased and installed the equipment directly, the Honduran taxpayer would have paid 77% less for it.

According to the Public Ministry’s indictment, Rishmawy acted as a “necessary accomplice” in this case, one of the many that make up the huge embezzlement of the IHSS. The same judicial process includes Mario Zelaya, who has already been convicted – and imprisoned – for other charges of embezzlement while he headed the institution. Prosecutors also argue that Social Security officials received money transfers – indirectly or directly – from Equipos Industriales through third parties or directly as checks, almost always with Rishmawy’s signature, from various banks, from July 2011 until the final delivery of the equipment in January 2012, for a total of 2 825 000 lempiras (around US$147,519).

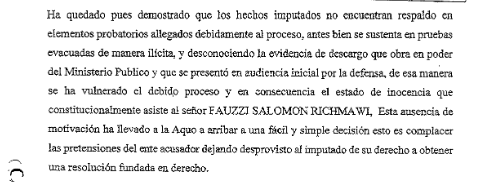

In the proceedings, the defense argued that the Public Ministry’s calculations are mistaken, there were no irregularities and that there has not been due process in this case.

At the main office of Equipos Industriales in Tegucigalpa, Fauzi Rishmawy and his son Juan José Rishmawy responded to the request for an interview made by this journalistic alliance. “I have never had a legal problem in my life,” said Fauzi Rishmawy. “I have worked hard for 45 years, my family legacy is very clean and all this has affected me in a terrible way, throwing me into problems that I have nothing to do with.”

He also added that Equipos Industriales, his family’s “mother company” continues to win public bids and to be a supplier of the Social Security Institute, and also of the Honduran Electric Energy Company(EEH). The latter, the businessperson says, represents 20% of its annual sales.

“We invoice more than one billion lempiras a year and I am not going to go and risk myself for 15 million or for 5 or for 10 million. We have won and we have lost but we have played clean,” he assures.

The case is now waiting for the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court of Justice to resolve an appeal, through which the defense seeks to have the indictment against Rishmawy revoked. The process was frozen by a suspension ordered by the high court while it reaches a final decision.

Contracorriente’s journalistic team in Honduras and the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (CLIP), within the worldwide collaboration lead by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) in the Pandora Papers project, found that on February 8th, 2018, Fauzi Rishmawy requested the creation of an offshore company in Hong Kong called Global Electric Trading Company Inc, as sole shareholder and beneficiary.

According to the incorporation documents, the company would operate as a supplier of Equipos Industriales S.A. and was created in Hong Kong, through the offshore services of supplier Overseas Management Company (OMC). In the application form for the creation of the company, Rishmawy reported that Global would have a cash flow of between US$3 million and US$5 million annually, and that the value of its annual holdings would be US$4 million. The partnership applicants reported that this company would be able to operate in Asia, Europe and the Americas, and that its assets would be “receivables, transitory inventory, sales and purchases, etc.” Finally, they said that the company would have its own account in Banco Ficohsa in Panama.

This and other documents linking Fauzi Rishmawy to offshore companies are part of a leak received by ICIJ containing confidential financial records of 14 offshore service provider companies, which create and manage shell companies and trusts in tax havens around the world.

Dubbed the Pandora Papers, these 11.9 million documents date from 1996 to 2020, and are in English, Spanish, Chinese, Greek and Russian, among other languages. The files, which were sent to ICIJ by an anonymous source in separate batches over several months, reveal connections to companies and businesses in more than 200 countries and territories. The collaboration of 615 journalists and 150 media outlets made it possible to investigate hundreds of them simultaneously in 117 countries.

The holding company and the supplier

Juan José Rishmawy and his father explained that Global Trading is still active and was created to avoid buying materials needed for Equipos Industriales from intermediaries, since its suppliers are in China.

“We created it in Hong Kong because that’s where our Asian suppliers are, we sell in the US and Central America,” says Juan José Rishmawy. “We are concerned about this narrative that you want to link the offshore structures with the IHSS case: here we have written everything down regarding these structures. None of them have a contract with the state, they are all shareholders of some companies. Others, as you mention there, are suppliers of Equipos Industriales, but ours is not the only company they supply … These are strategies that we put in place as a family to manage the estate, thinking about inheritance issues. They are not about evading taxes.”

“The reason why (Global) is a supplier of Equipos Industriales is due to a regionalization process,” explains Rishmawy’s son, who also showed the affidavits presented to the Revenue Administration System (SAR), where Global Electric is registered as a company related to Equipos Industriales.

With this supplier company in Hong Kong, the Rishmawys explain, they have been able to improve the prices of electrical materials and their company achieved better commercial conditions.

But those commercial maneuvers could have other explanations. The 2017 report published by a special commission of the Costa Rican Legislative Assembly – created after the ICIJ’s Panama Papers cross-border journalistic investigation with the purpose of “identifying mechanisms or practices used to evade taxes” through offshore companies – sheds light on this. A common use of these shell companies in tax havens, the report notes, is to serve as suppliers of goods or services. Thus, domestic companies declare payments of expensive services performed by these offshore companies which may be tax deductible, in order to pay less to tax authorities. However, the Rishmawys deny having used this company to avoid taxes.

If the tax authorities want to verify these payments of services -says the report of the Costa Rican Assembly- they have no way of knowing that the owners are the same, since the suppliers are covered by the secrecy that surrounds the offshore world.

A month before requesting Global Trading, in October 2018, Fauzi Rishmawy had applied for the creation of JAI HK Capital Inc., also in Hong Kong, for the sole purpose of “operating as a holding company of Global Electric Trading.” The same businessperson is also the owner of 100% of the shares of this holding company and is its beneficial owner. According to the documentation for the incorporation of the company, OMC would open a bank account in Panama for the client to manage the operations.

By placing Global Electric Trading under another offshore holding company, Rishmawy added an additional layer of confidentiality.

For setting up the two offshore companies, by wire transfer from his Panama bank account, Rishmawy wired OMC in Florida the sum of US$3,190.

“Is that (the layers of confidentiality) a benefit? Of course it is, in a country as insecure as Honduras. You benefit from confidentiality,” says Juan José Rishmawy. It is the same answer that the former president of Honduras himself, Porfirio Lobo Sosa, gives when asked about the creation of offshore companies and confidentiality: that Honduras is an insecure country. (See Pepe Lobo’s Secret offshore companies)

According to emails between OMC officials in Panama, originally Juan José Rishmawy Suárez, son of Fauzi, was going to be listed as director of JAI HK Capital. But they ultimately chose to appoint Jorge Rafael Carrasco Escobar,, a Honduran national.

Together with ICIJ, we sent a questionnaire to OMC asking them about the due diligence process they had in place when creating the companies JAI HK Capital and Global Electric Trading, and the origin of the money, among other details about this case. OMC replied in a letter that it cannot answer any questions about its clients due to confidentiality, but stressed that it complies with all applicable laws in the jurisdictions where it operates. “OMC is committed to compliance and maintains a robust compliance program, including due diligence policies and procedures,” it said in its response.

According to the Hong Kong Commercial Registry, the two companies, created respectively in January and February 2019, are still active today.

Carrasco, the right-hand man

Engineer Carrasco was also mentioned in the IHSS case.

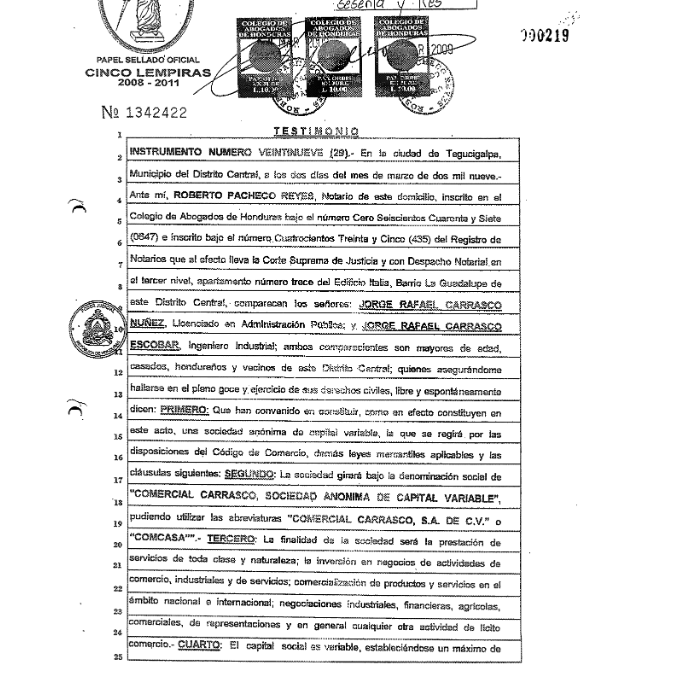

The Honduran Social Security had invited several bidders to the process of awarding a direct contract to supply four boilers and other electrical equipment to the Tegucigalpa Specialities Hospital, and the San Pedro Sula Northern Region Hospital. One of the invitees was Comercial Carrasco S.A. de C.V.

According to the Honduran commercial registry, this company was incorporated on March 2nd, 2009, before public notary Roberto Pacheco Reyes, by Jorge Rafael Carrasco Escobar and his son Jorge Rafael Carrasco Núñez. What attracted the attention of the judicial investigators was that this company had presented itself as a competitor of Equipos Industriales when Jorge Rafael Carrasco Escobar, secretary of the board of Comercial Carrasco, was himself an employee of Equipos Industriales.

In a memorandum, the IHSS Inspector certified that Carrasco Escobar had paid taxes as an employee of Equipos Industriales since June 1st, 2000 and that on October 25th, 2018 he continued to do so. It is thus clear how close Jorge Rafael Carrasco was to Fauzi Rishmawy and his company. Small wonder, then, that Rishmawy made him director of his offshore company in Hong Kong.

But Fauzi Rishmawy claims this should not be seen as suspicious. “Jorge Carrasco is an executive of Equipos Industriales, his mother has worked with me for 41 years and his sister works in the financial sector. The Carrasco family is like an adopted family. From Equipos Industriales there have been three companies of engineers who have left after working for us and, even being in Equipos Industriales, we give them the option of creating their own company. It benefits me because they buy materials from Equipos Industriales,” he says.

Regarding the process against Rishmawy for the alleged Social Security fraud, in December 2020 an anti-corruption judge issued a formal indictment against him. This means that the court felt that the Public Ministry provided sufficient evidence of the existence of the crime as required by Article 92 of the Honduran constitution. It also determined that there are “rational indications” of his possible participation in the crime. This resolution was confirmed by the Court of Appeals of the Anti-Corruption Circuit.

However, a few days later, this judicial decision was suspended following an appeal for legal protection by his defense. As long as the Supreme Court of Justice, through the Constitutional Chamber, does not issue a decision, the criminal proceeding cannot continue. Several months have passed since this suspension and the court still has not issued a ruling to determine whether Rishmawy will continue in the process or if, on the contrary, his process is closed.

Another offshore company shared with a banker

While Rishmawy was receiving payments for the equipment he sold to the Honduran Social Security Institute, which, according to the Public Ministry left him with extraordinary profits, in December 2011, another offshore company based in Panama – called Bolwell Overseas S.A. – opened an account in Panama’s Ficohsa Bank, with the signatures of Fauzi Rishmawy and Juan Carlos Atala Faraj. This bank is a 100% subsidiary of Grupo Financiero Ficohsa, headquartered in Panama.

In the bank’s forms, the directors of Bolwell Overseas S.A., incorporated on October 3rd, 2011, stated that it would have an income of US$70,000 per month and expenses of $36,000. As president, secretary and treasurer of the company Edgardo Diaz, Gina Martinez and Fernando Gil are listed. They are the same people who usually appear in such capacities in hundreds of other companies that, like this one, have been incorporated with the support of another offshore company provider based in Panama, called Aleman, Cordero, Galindo & Lee (Alcogal).

The documents from Alcogal’s file analyzed by this journalistic alliance, within the Pandora Papers project, reveal that the owners of Bolwell Overseas are two other offshore companies: Bamoore International Inc. with 4,000 shares and Enrey Investments S.A. with 6,000 shares. A later official certification from Bamoore (dated February 2015), states that the 10,000 shares of the company, at a value of one dollar per share, are owned by Fauzi Rishmawy. Another similar certification states that the 10,000 Enrey shares belong to Inversiones del Pacífico S.A. de C.V, itself a firm linked to the Atala family. As partners of Bolwell, it is reasonable that both Rishmawy and Atala had signatures on the shell company’s bank account.

According to reports from Alcogal itself, after Bolwell fell behind on the 2017 registry service (by US$350), it was finally dissolved on June 15th, 2018. Marilyn Valdes of Alcogal asked newspaper El Siglo in an email to publish the dissolution of the company, as mandated by Panamanian law.

Juan José Rishmawy explains that, “Like Bamoore, these are companies holding the shares of another company that collapsed, that was called ARMASA and that worked with timber; we were partners of others that you mention there, a company that went bankrupt and that is why it was closed.”

Rishmawy senior adds that the main client of ARMASA, Bamoore and Bolwell’s Honduran company, was called Ecosa and decided to withdraw its plants from Honduras because of “fiscal problems,” – referring to the fact that conditions in Honduras were not favorable and that this transnational company decided to locate its plants in Costa Rica and Mexico.

ARMASA was an old company, says Rishmawy Sr., adding that the timber business became very unsafe in Honduras and an incident at their plant made them decide to shut it down. “That was the reason for Bamoore and Enrey and from there they created a partnership that held the shares of ARMASA. We were partners not with Ficohsa, but with Inversiones del Pacífico, which belongs to the Atala family, majority partners of Ficohsa. But this was not with the bank but with the family,” he explains, emphasizing that none of these companies has any relation with sales to the Honduran state.

For the Rishmawys, offshore companies have been demonized, “If they were illegal, they would not exist,” says the businessperson with Equipos Industriales. “Many people have misused them, many politicians hide behind them. Seventy-four percent of the companies that are in the Fortune 500 – the largest companies in the world – are based in Delaware, which is a tax haven. It is not a sin.”

In an interview with this journalistic team on October 1st, Mario Bustillo, vice president of institutional relations for Grupo Financiero Ficohsa, explained that these businesses have nothing to do with the group, and that the Atala Faraj family has other investments and businesses outside the group that he does not know about, and therefore he cannot comment.

The Rishmawy fortune

In January 2012, according to the preliminary forensic audit report presented by a financial analyst for the prosecution for the judicial investigation, Rishmawy obtained the last payment for the boilers he sold to Social Security.

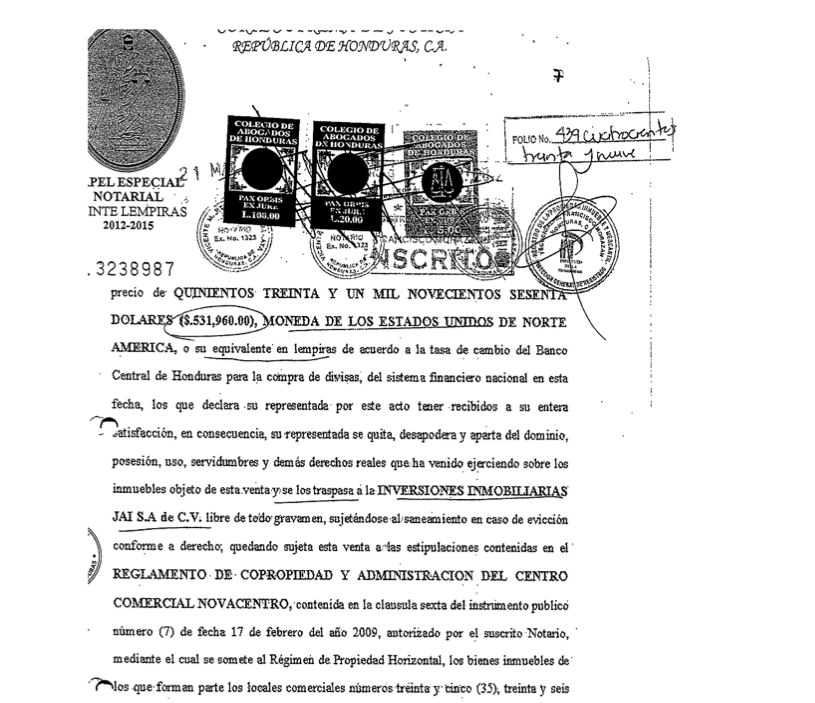

Two months later, in March, Inversiones Inmobiliarias JAI S.A. de C.V., a Honduran company in which Fauzi Rishmawy has 249 shares and his wife Julia Cristina has one share, bought three premises on the second floor of the Novacentro Shopping Center in the Honduran capital. A copy of this deed and the details of this purchase for US$531,960 are included in the documentation of the Public Ministry in the case.

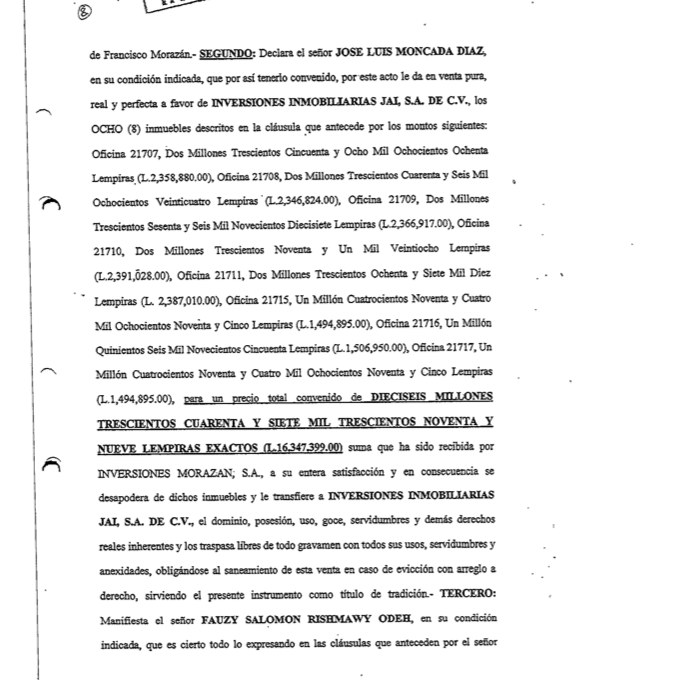

This entity also included in the process the purchase public deed of eight offices in the Centro Morazán Condominium in the San Felipe neighborhood of the Honduran capital for 16 348 399 lempiras (just over US$697,000 at the time) by Inversiones Inmobiliarias JAI S.A. de C.V., in September 2017.

Regarding the purchases of goods in Novacentro and Centro Morazán, the Rishmawys explained in the interview that Equipos Industriales was a supplier of the construction companies of these buildings and that the premises were a percentage of the payment for those businesses.

Between one purchase and the other, in 2014, Equipos Industriales also incorporated a new holding company, this one based in Honduras, called Equinsa Energy Holdings S.A. de C.V, with a nominal capital of half a million lempiras. The founders were: Fauzi Rishmawy as representative of Equipos Industriales; his children Juan José, Alejandro and Isabela Rishmawy-Suárez, the first as representative of Novus Holdings S.A. de C.V.; the second representing Sigmar Holdings S.A., also a variable capital company; and the third in her own name. The commissioner of Equinsa Energy is the man he trusts, Jorge Rafael Carrasco Escobar.

Fauzi Rishmawy explained that Novus and Sigmar are two companies registered in Honduras that are the owners of Equinsa Energy, a solar panel installation company.

“I am going to be 70 years old soon, I have to have replacements in the companies and who am I going to partner with, am I going to partner with strangers or with my family?” says Rishmawy.

Expansion into the United States

This investigation was also able to ascertain that on September 4th, 2012, another company with a similar name, JAI Investments Ltd, purchased suite A2109 at 1865 Brickell Avenue in Miami for $900,000, as recorded in Florida’s Dade County property registry. According to the Rishmawys, JAI Investments Inc. is a company of theirs, also created in the United States.

Today, out of that suite in Brickell Avenue, the company Gold Sails Investment Corp operates. It was registered in Florida in May 2016, and its managers are Alejandro Rishmawy and Juan José Rishmawy, sons of Fauzi.

In November 2016, with Juan José and Alejandro as managers, a limited liability company called Equipos Industriales LLC was created in Miami, with offices in Coral Gables, at 999 Ponce de León Boulevard. According to the Dade County registry in Florida, this office is not owned by the Rishmawys.

“You are mentioning companies owned by my children in the United States. They are American citizens. They are LLCs, that information is public, they are companies that file taxes,” said Fauzi Rishmawy, explaining the origin of these companies. His son Juan José added that, “We have the right to have companies if they are fully public LLCs, both Gold Sails and JAI are taxed in the United States. You can’t play with taxes there: either you pay taxes or you are fined and go to jail.”

Yet the contracts kept flowing

The contract of Equipos Industriales with the Honduran Social Security Institute that led Rishmawy to face, according to him, his first legal issue, has not been the only one that this company has had with the IHSS, nor with the Honduran state.

In the public procurement registry Honducompras, Equipos Industriales S.A. de C.V. is listed with 41 contracts between 2016 and 2021, totaling 15.5 million lempiras in minor purchases. In February 2019 it signed another contract for almost 6 million lempiras (US$140,000) with the same IHSS. Even after the accusation of alleged fraud against Rishmawy last December, Equipos signed a contract with the Mayor’s Office of San Francisco de Yojoa, in the department of Cortés, in January of this year. It is also a supplier of the Honduran Energy Company (EEH).

It is not illegal to create companies in tax havens or to manage bank accounts through an offshore service provider such as OMC or Alcogal. Nor is it illegal to create companies in Florida. Yet a serious charge such as defrauding the state, now faced by businessperson Fauzi Rishmawy, raises a lot of questions.

“Public contracting doesn’t even make for 5% of my sales, 10%, at most,” the businessperson assured. “EEH is indeed the most important customer for Equipos Industriales, almost 20% of the annual sales volume. Go to them and ask them why they buy from me; it’s not because of my pretty face,” explains Rishmawy, who insists that the IHSS case in which he has been involved has been handled politically and not in the interest of justice.

“If they suspended the process, that would be because the Prosecutor’s Office doesn’t have anything. They are looking for cases where there are none: the IHSS case is hot and will continue to be hot for the next few years and the more they dig, the more they will find. Sometimes it serves as a distraction from other bigger things,” he says.

Rishmawy did not go into more details about his judicial case because, as his defense attorney Ritza Antunez had warned this journalistic alliance days before, his client’s appeal for legal protection is still pending resolution and she cannot discuss the subject further.

The IHSS case brought thousands of people to the streets to protest, as part of the Indignant Citizens’ Movement that shook Guatemalan and Honduran politics. In Honduras, citizens demanded the resignation of President Juan Orlando Hernández because several checks from the embezzlement operation that reached US$300 million found their way to his 2013 election campaign accounts. People also demanded an international investigation commission like the CICIG in Guatemala, after which, in 2015, the Support Mission against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (MACCIH) was installed. Hernández’s own government dismantled it in 2019.

Rishmawy says he is awaiting the resolution of his case before the courts to prove his innocence.