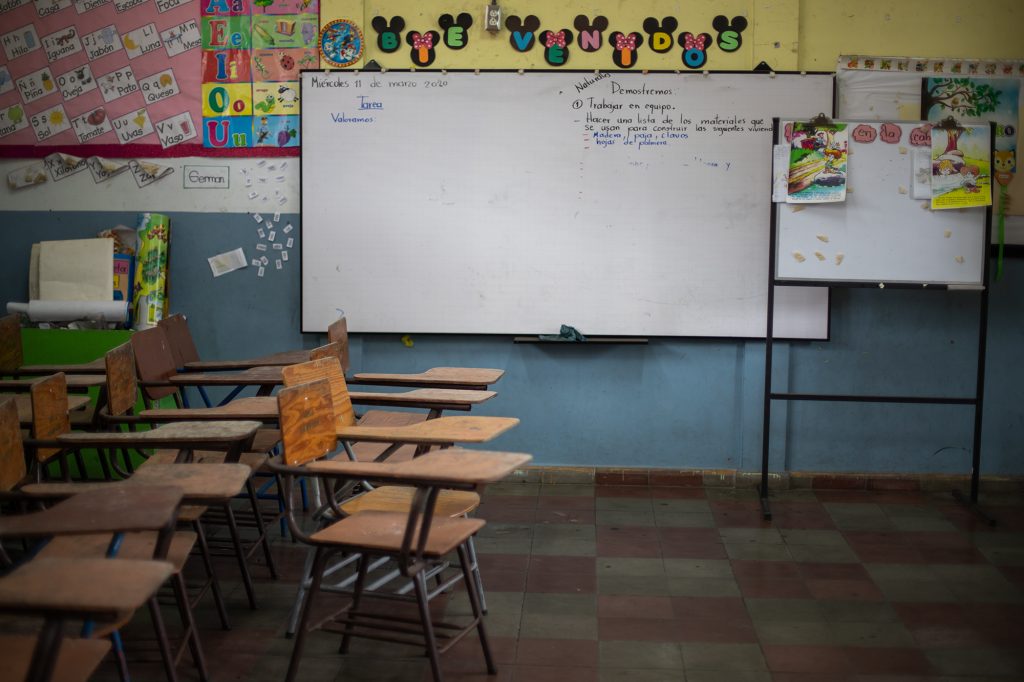

In-person classes were suspended in March 2020 when the pandemic hit Honduras. One year later, the pandemic is still out of control and the country is preparing to start a new school year in very unstable circumstances.

By Allan Bú

Photos by Martín Cálix

Every Saturday, for about three months last year, a vegetable vendor stopped by Auxiliadora’s house to pick up homework from six kids in her village near Puerto Cortés in northern Honduras. They had no Internet at home and no cell phones. When the pandemic hit Honduras in mid-March 2020, these students weren’t able to join the virtual classes because their parents couldn’t afford an Internet connection. Once again, the Honduran government did nothing and failed to live up to its obligation to provide free education to its citizens. The six students were left to fend for themselves.

Data obtained by Contracorriente from the Ministry of Education indicates that 20,398 elementary school students dropped out of school in 2020, and 7,746 students dropped out of secondary school. After the first cases of COVID-19 were detected last March, the Hernandez administration mandated a lockdown that suspended in-person classes. But this quarantine and the ongoing curfew failed to stop the spread of the virus. On February 5, official sources reported a total of 152,225 coronavirus cases and 3,669 coronavirus-related deaths.

Stay on top of Central American news and analysis: Subscribe to our weekly, English-language newsletter.

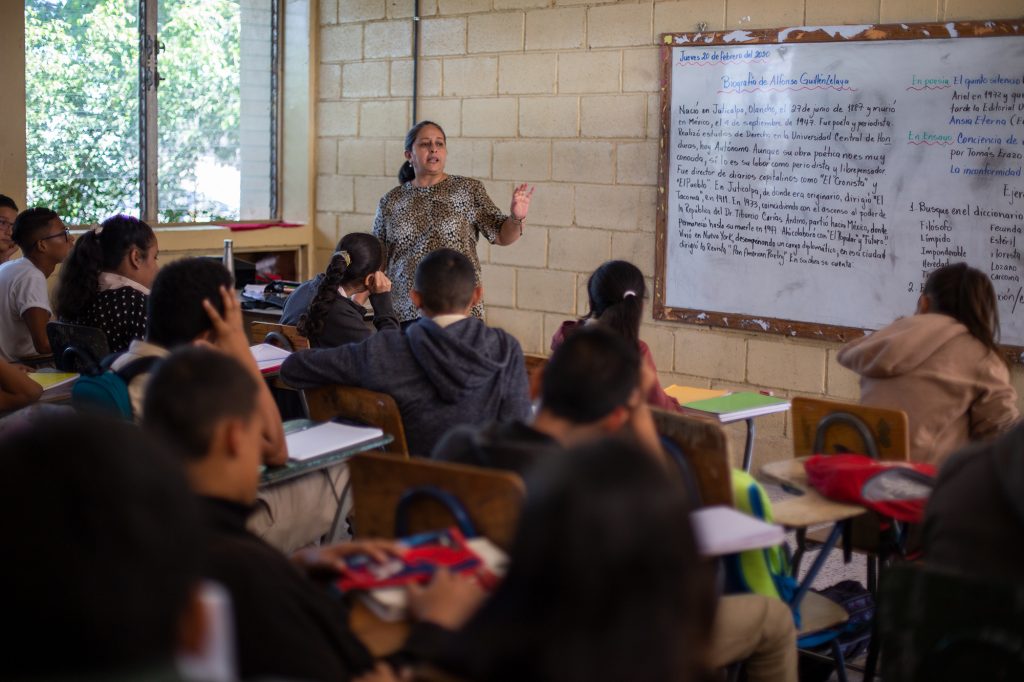

Auxiliadora has been teaching for 23 years. Before the pandemic, she taught afternoon classes in a village near Puerto Cortés and would always prepare her classes the day before. To get to work on time, she had to leave at 10:30 am and take two buses to the school. She would first eat lunch before starting her day at 12:30 pm. The students would line up to enter the classroom, and more than a few would bring her some fruit. But then the pandemic tore her away from the classrooms where she has worked for almost half her life. “I miss the mamones,” she says, talking about the quenepa fruit her students would bring when it was in season.

When classes were switched to online learning last year, Auxiliadora began making copies of teaching materials and assignments for her students to pick up at someone’s home near the school. This became too expensive for her, so instead she started making phone and video calls, and sending messages. She soon found that only 17 of her 37 students regularly submitted homework assignments. Others only submitted assignments occasionally. Six students had no way to send and receive assignments, and seven disappeared altogether.

Ministry of Education data obtained by Contracorriente shows a decline in school dropouts. In 2019, 105,971 students dropped out of school, slightly more than triple the number of dropouts in 2020. Hard-working teachers all over the country contributed to this positive outcome by adapting to the circumstances of the pandemic.

The biggest challenge for Auxiliadora’s students was connecting to the Internet, since only five of them have wifi at home. Internet connectivity is a problem throughout Honduras. According to La Prensa, the National Telecommunications Commission (Comisión Nacional de Telecomunicaciones – CONATEL) estimates that 40% of the population had wifi or mobile Internet access in 2020. Small villages evidently have even lower rates of Internet connectivity.

While Auxiliadora tried to figure out how to send and receive homework assignments so her students wouldn’t give up and drop out, a vegetable vendor became an unlikely lifeline for six kids with no Internet. One day she decided to ask him if he would drop off the schoolwork as he passed through the children’s village. “He would then text me to confirm that the schoolwork had been delivered,” said the teacher.

Despite her best efforts, Auxiliadora thinks that the children’s learning has suffered over the last year. “If I even covered half the math topics, that was a lot. There are some topics that I couldn’t address properly through online classes. As an experienced teacher, I felt that it just wasn’t going to work,” she said.

Auxiliadora considers the 2020 school year to be a failure because she had some teaching plans that couldn’t be accomplished remotely. For example, she planned to have her students start doing presentations. “I was excited about this and even bought a speaker and microphone,” she says.

Ministry of Education officials claim that approximately 80% of the student population was served through radio, television and online learning last year. However, this didn’t work out for Auxiliadora’s students.

Arnaldo Bueso, the education minister, told Contracorriente that, “All these resources helped, but nothing can replace the teacher-student, in-person learning experience. We expect to be more aggressive this year in providing free Internet, and the National Telecommunications Commission is working on this.”

The Pilot Program

The 2020 school year ended and many students who didn’t meet basic requirements were promoted to the next grade level anyway. The pandemic put even more stress on Honduras’ obsolete education system.

The pandemic marches on and hospitals are overwhelmed again, like they were last July and August. The rate of positive COVID-19 tests continues to rise in the departments of Cortés, Atlántida and Francisco Morazán.

The country’s public health crisis looms large as the Ministry of Education gets ready to start a new school year. When in-person classes were suspended last March, the country only had two coronavirus cases. Now 3,669 Hondurans have died from the disease.

This is the situation in which Honduran children will return to school. Bueso described a pilot program to be initiated in 18 schools without any active COVID-19 cases and in areas where the pandemic has been contained. “The idea is to open up these schools with all the necessary biosafety measures in place to protect students and teachers,” he said.

Bueso said the pilot program will be initiated once educators from the selected sites have evaluated current conditions. “We understand that conditions vary around the country. The pilot program participants must first obtain authorization from our national emergency management system [Sistema Nacional de Gestión de Riesgos – SINAGER] before they can open. The objective of the pilot program is to evaluate whether these new measures are effective so that we can systematically open schools in low-risk areas once the pandemic subsides,” said Bueso.

Teachers and students will begin a new school year on March 1, according to an official communication sent by the Ministry of Education to the departmental school districts. The government has created a 30-page plan detailing pandemic-related guidelines for schools (Plan de Atención para la Protección de las Trayectorias Educativas de los Educandos de Pre Básica, Básica y Media: Trienio 2021-23).

This plan provides general guidelines for safely opening schools during the ongoing pandemic. Once implemented, the Ministry of Education expects the plan will enable children and youths to have timely access to education. The plan’s simplified but effective curriculum aims to equip students with required competencies and skills over the next three years.

But Guadalupe Ruelas doesn’t agree. The director of Casa Alianza, a Honduran non-governmental organization that serves at-risk children, notes that in spite of all the government money and international aid spent on education, the country still doesn’t have a curriculum adapted to the reality of its children. “We don’t have a suitable educational system for the children of Honduras. It’s a rote teaching process that is obsolete,” said Ruelas.

The Ministry of Education’s plan envisions three learning methods for the new school year: in-person classes, online learning and blended learning. The plan recommends that schools select the most suitable approach for their specific circumstances, taking into account the status of the pandemic in their communities.

School administrators should coordinate with SINAGER and communicate regularly with teachers, students and parents. Each school should prepare an action plan based on the learning method selected for each grade level, and seek to obtain parental approval for this plan.

Back in Puerto Cortés, Auxiliadora will have to adapt to a blended learning approach for the new school year. Twice a week, she will teach in-person classes for two hours. There will be no recess and everyone will try to follow basic biosafety measures. She told us that attendance for the in-person classes is voluntary.

“Every teacher must prepare and submit a schedule of activities for approval by education officials,” said Auxiliadora.

But things will be different for a school in the Villa Real neighborhood of Villanueva, Cortés. Starting on February 15, Beatriz will meet with her students to review what was learned last year, but not on school grounds. All teaching will continue to be completely virtual. Cortés has consistently had the country’s highest number of coronavirus cases since the beginning of the pandemic. This department recently reported 45,640 cases, or 31.6% of the total number of cases in the country.

Principals from educational institutions in the department of Ocotepeque decided in a recent meeting that most of their schools will hold in-person classes three days a week.

Selvin is a teacher from Sensenti in the municipality of Ocotepeque. He is scheduled to teach in-person classes on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday each week. Since his school doesn’t have many teachers, he has been assigned several grade levels and will teach each grade one day a week from 8:00-10:30 am. To avoid close physical contact, there will be no recess for students. Selvin will teach four basic subjects: mathematics, Spanish, natural science and social sciences.

But one glaring omission in the Ministry of Education’s new plan are guidelines on biosafety measures for teachers and students. “We feel abandoned ⎼ there’s no commitment from our government. We’re thinking about meeting with municipal officials to discuss this situation,” said Selvin. The teachers want to request biosafety support.

Secondary schools will also select learning approaches that meet the needs of their individual communities. At the Manuel Pagán Lozano school in San Pedro Sula’s López Arellano neighborhood, teachers can choose whether to work in their classrooms or not. But no classes will be taught there, as students will only be allowed to pick up and drop off educational materials and homework. Everything else will continue to be done online.

Education Minister Arnaldo Bueso says that the vast majority of the country’s schools will continue with online learning delivered over various platforms, as there will be over 130 television and radio channels and Internet platforms for this purpose. Students who don’t have access to the technology needed for online learning will be given workbooks. When Contracorriente asked the minister if the pilot program includes all the schools we interviewed that plan to have at least one day of in-person classes, he only replied, “They need to comply with the guidelines established by the Ministry of Education.”

The Ministry of Education’s plan describes inter-institutional, local, and national collaborations as well as alliances with international organizations that will “offer students a learning environment that maintains appropriate educational, socio-emotional and health conditions.” However, the teachers we interviewed told us that teachers and students would have to provide their own biosafety supplies.

The implementation of the government’s plan for a gradual, safe and flexible return to school will vary according to the specific needs of schools in different geographic zones. The one commonality is that the government will not provide the resources for the successful execution of the plan.

Based on the Ministry of Education’s plan, over the next three years the national curriculum will be adapted to the approved teaching channels (in-person, virtual and blended) and techniques, allowing enough flexibility to adjust to the different challenges experienced in the country’s regions, departments and municipalities.

The plan looks good on paper, but the reality of Honduras’ current situation may thwart the best intentions. Auxiliadora had 31 students last year, seven of whom couldn’t be promoted to the next grade because they didn’t have Internet access. She has 28 students enrolled this year, but three don’t have phones. The Ministry of Education’s plan includes an initiative to contract Internet service providers to provide free Internet access in education centers.

The plan also states that an inclusive and equitable process must offer teachers and students digital or printed educational tools that facilitate any type of learning on any platform. Auxiliadora recalls that before the pandemic, she paid for most of her teaching materials out of her own pocket. “Teachers have to find a way to get [the materials], and it usually ends up coming out of our paychecks,” she said.

Auxiliadora made a point of telling us that she didn’t want to make any political comments, but recalled that the National Party was not in power the last time they received educational materials from the government. “We haven’t received anything for years. I hesitate to say this, but the last time we got anything, [Manuel] Zelaya was in power (2006-09). It wasn’t very good, but at least it was something,” she said.

Record levels of neglect

Guadalupe Ruelas says that the educational system in Honduras had been “completely neglected” before the COVID-19 pandemic, but that this new, challenging school year offers opportunities to get education back on track in Honduras. “I think we should always be rethinking our country’s education system in terms of coverage, suitability and quality. Otherwise, our society will stagnate,” she said.

The Ministry of Education has a 2021 budget of 32.2 billion lempiras (US$1.3 million), which is slightly more than 11% of the country’s total annual budget of 288.8 billion lempiras (US$12 billion). Almost 80% of the Ministry of Education’s budget is for teacher salaries. There are 6,379 pre-school teachers, 51,961 elementary school teachers and 32,296 secondary school teachers in Honduras.

Even though Honduras has prioritized the national defense and security sectors, it does budget a great deal of money for education. Yet the education system is still precarious. The 2019 statistical report issued by the Central Bank of Honduras indicates that the country’s illiteracy rate in 2019 was 11.5%, and that on average, the eighth grade was the highest level of schooling attained by Honduran students. This is only slightly better than El Salvador, which has the lowest literacy rate (88%) in Central America.

Guadalupe Ruelas claims that before Tropical Storms Eta and Iota devastated the Sula Valley, 75% of the area’s school infrastructure was already in poor condition, and that an opportunity was lost when no improvements were made while schools remained empty due to the pandemic. The condition of the schools in this area deteriorated even more after the storms and flooding. “The pandemic highlighted the problems in the educational system, but it also aggravated the problems of scope and coverage, so now we have fewer children in the educational system,” said Ruelas.

Government officials will periodically review teacher vacancies over the next three years to adjust to demand. Rural areas will receive greater focus because most teachers in these areas have to teach several grade levels, and sometimes schools only have one teacher.

The most vulnerable people in Honduras and around the world were the ones hit hardest by the pandemic. This is also true for the country’s education system. Children without smartphones or whose parents didn’t have 25 lempiras (US$1) for Internet access were excluded from the educational system.

Guadalupe Ruelas says that we often talk about underdevelopment and marginalized people as if they’re a minority, but in Honduras, the marginalized are a large majority. “According to UNICEF, 77% of Honduran children belong to poor families. There are more children than adults living in poverty, she says. Honduras lags far behind international standards because approximately four million (49%) school-aged children don’t go to school.