The Honduran government has promised that the construction of 14 dams will prevent the severe flooding that the country experienced during tropical storms Eta and Iota late last year. But these controversial projects are marked by a lack of transparency and are being developed with little community input.

Photos by Martín Cálix

Once the El Tornillito dam is built, the town of Chinda in the municipality of Santa Bárbara will be transformed into “The Venice of Honduras,” boasted Hidroeléctrica El Volcán (Hidrovolcán), a power generation company, in a community meeting with the residents of this small town in western Honduras. The dam will divert the river towards the town, turning it into a tourist attraction, said the company’s representatives to the citizens of Chinda, an area plagued by high unemployment and poverty.

But this future Venice remains waterlogged in the aftermath of tropical storms Eta and Iota. Fourteen families from the Brisas del Ulua neighborhood, about 500 meters from the Ulua River, are still sheltering in an elementary school after they lost their homes four months ago.

The houses in this neighborhood, most of them made of adobe and mud wattle, are still buried in sand and dry mud. Their owners are slowly cleaning them out so they can return home and get on with their lives.

María and her husband Pedro are among the displaced families. In the afternoons, they work on the foundation for a temporary house they’re building on the sand that now covers the property they’ve been improving for the last fifteen years. Before the storms hit, they were on the verge of selling the property to Hidrovolcán, the developer undertaking the largest privately-funded hydroelectric project in Central America. The dam reservoir is projected to cover the entire area washed away by the river during the storms.

At the end of November last year, President Hernández announced that this dam, and at least three more, would be declared “priority projects” that would control flooding in the Sula River Valley. He then issued executive order PCM 138-2020 to quickly approve, build and operate 14 projects through a trust established with private banks that will gain absolute control over the country’s energy sector.

President Hernandez makes energy sector decisions

“We’ve been talking to people living in the Sula Valley region about our top priority− the national strategic projects of building hydroelectric dams at El Tablón, Jicatuyo, El Tornillito and Los Llanitos,” said President Hernández on November 27.

Less than a month later, the president and his cabinet issued PCM 138-2020, an executive order that cited the destructive impacts of hurricanes and tropical storms Eta and Iota in order to prioritize 14 dam construction megaprojects. The executive order declared the design, construction, expansion and operation of these dams a matter of national interest. These priority projects include the dams at El Tablón, Jicatuyo and Los Llanitos. The El Tornillito dam was not declared a priority project and will not be subject to the executive order as it continues on its current course of development.

The executive order incorporates these projects into the Banco Atlántida-managed Energy Generation Trust Fund established by Legislative Decree No. 373-2013 to build hydroelectric and flood containment dams. This decree endows the bank with broad authority over the country’s energy sector. Furthermore, these projects have already been legally established and certified as viable, and have been issued all the permits required by Honduran law. Therefore, new hydroelectric projects no longer need to socialize their plans with local communities or solicit their input.

Luis Cosenza Jiménez, an electrical engineer and former campaign manager for the National Party, published an article claiming that Legislative Decree No. 373-2013 “… contradicts the country’s law regulating the electricity generation industry… which requires the System Operator to prepare a plan for expanding its electricity generation capacity, and that the projects included in this plan are subject to an international public bidding process. The legislative decree contradicts both requirements as the Banco Atlántida trust now has the authority to decide which projects move forward and when, thereby disregarding the System Operator’s plan. Moreover, ENEE (Empresa Nacional de Energía Eléctrica), the country’s national electric company, would be obligated to buy the energy generated by the project, eliminating the international public bidding process. In short, the Legislative Decree effectively destroys the sector’s institutional framework.”

Cosenza also notes that the law regulating the electricity generation industry is a legislative decree which takes precedence over an executive order. Therefore, the new executive order is null and void because it cannot supersede the existing law. To address this obvious legal contradiction, the National Congress established a special commission of 11 legislators to create a mechanism enabling the executive order to take effect.

Luis Redondo, a congressperson from the Innovation and Unity Party (Partido Innovación y Unidad – PINU), immediately opposed the executive order, claiming that experts consider this to be “one of the biggest robberies in the country’s history, since it aims to destroy the ENEE once and for all, divide up the nation’s rivers, and take control of all the water. Coincidentally, it is now being listed on the New York Stock Exchange – something that has been planned for years.”

The opposition parties in the National Congress have denounced the move to allow private banks to acquire public debt for dam construction, and contend that this executive order would also violate the rights of indigenous peoples by eliminating the requirement for community input and consultation.

Redondo claims that this is not a partisan issue, but rather a ruse that uses the Sula Valley floods as an excuse to hand over water resources to private enterprise. However, the executive order includes projects that are not located in this part of the country.

The proposed dam on the Choluteca River near San Fernando and Morolica is an example of a project that is far from the Sula Valley. National Party presidential hopeful, Mauricio Oliva, has made this dam one of his campaign promises, declaring that if elected, he will build it during his first year in office.

The Honduran Association for Renewable Energy (Asociación Hondureña de Energía Renovable – AHER), a non-governmental advocacy organization, also opposes the executive order and has stated, “We recently sent a letter to the International Monetary Fund representative in Honduras with our reasons as to why this executive order should not proceed. Most importantly, the National Congress should not use it as a pretext for modifying the existing law regulating the electricity industry because this would be a step in the wrong direction.”

Another project included in the executive order is the construction of the Los Llanitos and Jicatuyo dams, first identified in 1979 as having hydroelectric potential. These dams would impact a number of communities in Santa Bárbara department, including the village of La Isla in the municipality of Colinas.

There is only one way to get to La Isla from Inguaya, a community near the town of Santa Bárbara − a small, five-passenger launch with a boombox that only plays rancheras, piloted by a man who has navigated the Ulúa River his whole life. Doña María de los Ángeles and don Emilio live in a home close to the river and the entrance to the community, a home that was heavily affected by the November storms.

“I looked at the river at about 9:00 pm and saw that it still hadn’t spilled over its banks, so I told my wife that we were safe. But when I woke up around 2:00 am, it was already up to the house,” said don Emilio. Doña María interrupts to say that all they could do was “fall on our knees” and pray to God for protection. Their humble homestead had chickens and pigs, as well as watermelon, banana, mango, avocado and corn crops. Although it’s been hard to lose all the crops, they’re thankful that most of the animals survived the flood.

“We didn’t expect anyone to rescue us, but no one has come by to give us even a little bit of food, not even the mayor,” says doña María.

Juana María Baide, another La Isla Colina resident, says that they don’t know much about the dams because “we don’t have any information − we’d like to know what could happen if they build the dam. It’s supposed to bring jobs and there are no jobs here, but water released from the dam during storms could affect us − we could be flooded.”

People are afraid that the dam will cause catastrophic flooding in their communities, a fear that stems from the rumors that the Sula Valley floods were caused by the ENEE’s undisclosed water releases from the El Cajón dam. According to information obtained from the ENEE by El Heraldo, 623 million cubic meters of water were released from this dam from November 14 to 28, 2020.

Juana says they never get any information because they’ve been completely abandoned. The only help they received after the storms came from a TV station and a church. She says no politicians ever come to this area, not even during political campaigns.

A solution to the disaster − the El Tornillito dam

According to official data, Eta and Iota caused the deaths of at least 100 people and affected a total of four million people. The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) reports that the country suffered an economic loss of 45.67 billion lempiras (US$1.89 billion). The Honduran government seized this opportunity to include dam construction in its Sustainable Reconstruction Plan (Plan de Reconstrucción Sostenible), which it says also focuses on rebuilding road infrastructure, agricultural recovery in affected areas, and aid to micro, small and medium enterprises.

The most destructive climate disaster in the last 20 years thus became the perfect pretext to push a policy of extractivism that has been slowed by persistent community opposition. At times, this conflict has led to the murder of indigenous leaders and environmentalists.

The president is the primary advocate for building dams for flood prevention, and says that US$1.5 billion will be needed for these projects. Designating these projects as a national priority would result in a total lack of consultation with the affected communities.

On November 27, Hernández stated, “This motion to designate these projects as a national priority is an opportunity to end a fruitless debate, because many people are opposed to the dams− they don’t want to relocate.”

Chinda is a small municipality of 68.4 square kilometers, inhabited mostly by indigenous Lenca people in the department of Santa Bárbara. The El Tornillito hydroelectric project on the Ulúa River is already under construction, and will eventually produce 160-200 megawatts of electricity. President Hernandez’s plans referred to it as a priority project even before the executive order was issued. Even though the families living in the Brisas del Ulúa neighborhood, which will be covered by the dam’s reservoir, support construction of the dam and are willing to relocate, their meager incomes and lack of job opportunities prevent them from living in safe areas, resulting in the loss of their homes.

“The river was swollen by 4:00 pm, but we never thought it would rise all the way to our homes. Then we lost electricity and it was all dark. We realized that the rain wasn’t going to stop, and around 7:00 pm we saw that the river was close. We didn’t have time to get our belongings out,” says Maria, who we found with her husband Pedro, trying to rebuild their house out of the rubble.

With the raging river at their doorstep, Maria told her daughters to bundle their clothing in the bedspreads to take with them. This clothing, a donated bed and a blurry photo of the family are all they have four months after the disaster. María is 35 years old, and is almost always accompanied by her four daughters. Returning to where her house used to stand, her eyes got teary as she made a list of the things left behind: beds, pictures on the wall, wardrobes, a shower, a laundry sink.

“We went back the next day to look down from the hillside and saw that our house was gone, there was nothing left, just sand,” she said.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic shut down most of the country in March 2020, Maria and her husband were negotiating with Carlos Madrid, the engineer in charge of land management for Hidrovolcán. Honduran law requires projects of this type to buy affected properties from their legal owners, so Hidrovolcán was in the process of negotiating the purchase of their property and possible relocation. It was also negotiating to buy the property of a brother who lives in the United States. The preliminary agreement indicated a purchase price of over 800,000 lempiras for the two properties. The pandemic put a halt to the negotiations and, according to María, Madrid has now told her husband that the company is no longer interested in making an offer since the flooding demonstrated that they live in an uninhabitable risk zone.

The El Tornillito dam project estimates that the reservoir will flood the Brisas del Ulúa area and the entrance to Chinda. The dam itself will be located between the municipalities of Villanueva and San Antonio in Cortés, and will affect the Santa Bárbara communities of Concepción del Norte, Chinda, Trinidad and Ilama.

The El Tornillito hydroelectric project will cost US$600 million and will be the second largest dam in the country after El Cajón. The November 2020 floods are expected to delay construction for at least a year. After losing everything in the floods, the residents of Chinda hope to reach an agreement with the project developers that will give them a chance at a dignified life.

“Because of our desperate situation, my husband asked Madrid about the deal we had, since we could use that money to buy beds and clothes. But he said that the company was no longer interested in buying the property, and anyway it wasn’t worth that amount anymore. But we have our property title, so I told my husband that we better try and go back to where our home used to be,” said Maria, with a worried look.

Dennis Rivera is a Brisas del Ulua resident who received a plot of land donated by Mayor Mirian Lopez. He says that Hidrovolcán representatives told him that he couldn’t go back there because it was a risk zone. They also told him, “If the mayor placed you there, then she’s responsible for relocating you.”

According to the flood victims, the municipal government has told them that because they can’t be relocated right now, they will be given zinc roofing to rebuild over the ruins of their homes. They have also been told to wait for help from Hidrovolcán.

Mirian López, Chinda’s mayor, told Contracorriente in a telephone conversation that despite the disaster, Hidrovolcán cannot back away from its obligation to purchase the land, and promised us a more extensive interview. However, she did not respond to our calls after this brief conversation. Mirian Lopez is running for reelection as the National Party’s candidate and was campaigning in other communities in the municipality when we requested the interview.

“It’s regrettable that they are being told to return to an unsafe area. If another hurricane hits them, these people will be risking their lives. That area will eventually become our responsibility and we must protect and relocate these people. But it is not our responsibility yet,” said Karen Gallegos, Hidrovolcán’s public relations manager. Regarding statements made by company personnel to the victims about their property being worthless, she said that this is not the company’s official position.

“Our company cannot dodge a responsibility that clearly belongs to us. If someone has a free and clear title to a property in an area affected by the Hidrovolcán dam or reservoir, the company will negotiate with them, or perhaps has already done so,” said Gallegos.

Although most of the affected families haven’t finalized agreements with Hidrovolcán for the sale and relocation of their homes, a group on the other side of the Brisas del Ulua neighborhood did make a deal before the storms. The company is building homes for five families who lost everything.

Gallegos explained that they no longer have the resources to buy land and build homes for all the families they were negotiating with. She said, “People think that the company and investors are swimming in money, and this just isn’t true.”

According to Hidrovolcán’s articles of incorporation dated August 18, 2005, the company’s largest shareholder is Napoleon Larach, president of Electricidad de Cortes S.A. (Elcosa), one of the main thermal energy generators in the country. Elcosa and Hidrovolcán are part of the Inversiones y Representaciones Electromecánicas (Iresa) group that operates plants producing 493 megawatts nationwide; almost 30% of the 1,670 megawatts that the country consumed in 2020.

Hidrovolcán claims that the entire process of project creation, feasibility study and contracting has strictly complied with the law. However, it recognizes the energy industry’s history of corruption and violence over the last ten years. “If you want a transparent project that complies with the law, the process takes longer,” said Gallegos.

When asked about the indigenous peoples affected by the projects who are demanding free and informed prior consultation in accordance with Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO), Gallegos said, “We have asked the government to establish the rules for this consultation, as this is their responsibility. Our responsibility is to build consensus, which we have done.”

The Honduran government and indigenous organizations have been working on the creation of a consultation mechanism since 2012. The last attempt was in January 2020 with the creation of a commission chaired by Óscar Nájera, a National Party congressional representative from Colón, an area known for drug trafficking, land disputes, African palm cultivation and mining.

Nájera held a meeting with representatives from indigenous organizations to discuss the initiative, and said in a subsequent press conference, “We started something today that will go down in our country’s history, and we were greeted by the love, affection and above all the humor of the Indians (sic), made up of the Afro-Honduran and indigenous peoples.”

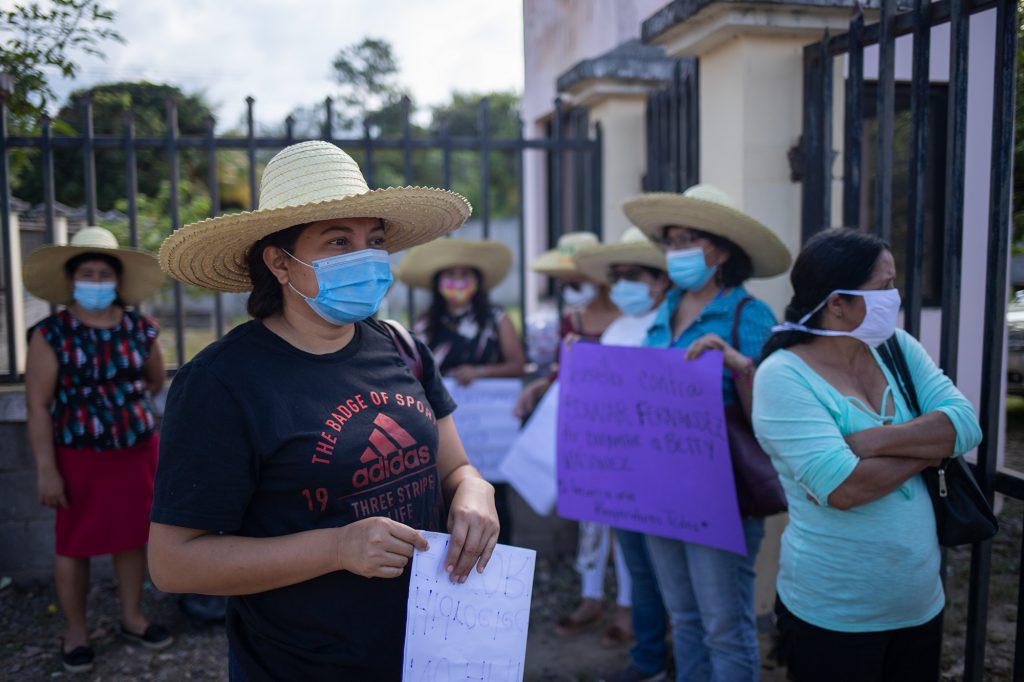

The indigenous organizations reacted by demonstrating days later in front of the National Congress to present their analysis of the bill and declare their opposition to it. They claimed that the law does not comply with international standards as it does not require reaching an agreement with all indigenous groups affected. In addition, the homogeneous approach of the consultations does not recognize the differences between various indigenous groups.

When asked about opposition by organized indigenous and peasant groups to the El Tornillito project, Gallegos said they have not encountered any opposition and that company representatives always feel welcome there. “Nobody in Chinda is saying ‘You’re going to destroy our Lenca roots,’” said Gallegos.

Gallegos recalled the assassination of Berta Cáceres, saying that while the circumstances of her murder remain cloudy, “her death has consequences that will affect us all for many years to come.” She then noted, “It’s important to recognize that not all environmentalists died just because they were environmentalists.”

Data collected by Contracorriente for the Tierra de Resistentes project demonstrates that at least 138 environmental activists in Honduras were murdered because of their activism.

The Santa Bárbara Environmental Movement

The storms, plus the government’s position that dams are the only flood-prevention solution, led to more threats against environmental activists like Betty Vásquez, coordinator of the Santa Bárbara Environmental Movement (Movimiento Ambientalista Santabarbarense – MAS). MAS is one of the few groups involved in community-based organization and training in Santa Bárbara, a department with 60 power generation concessions, and the second highest number of natural resource exploitation projects in the country.

The November 25 television broadcast of the Al Cierre news program featured journalist Edward Fernandez declaring, “Northern Honduras wouldn’t be all torn up right now if those dams existed. As for the environmental activists, that girl Betty hasn’t shown her face even to give away a few bags of food. Those who opposed the El Tornillito dam haven’t dared show their faces to give away bags of food to victims because they know in their hearts that they’re guilty, that these people have lost their homes and everything. Those who have opposed the dams are to blame.”

Contrary to Fernandez’s accusation, MAS has been providing food aid since late November to victims in various Santa Bárbara communities. Betty Vásquez stores the bags at home and delivers them to beneficiaries, sometimes crossing rivers by canoe to make the delivery. On January 25, Honduran Women’s Day, Vásquez took dozens of food bags across the river to La Isla Colina, one of the villages threatened by the construction of Los Llanitos dam.

Betty advocates for protecting natural resources through active citizen participation and public events such as the town hall meetings in which the entire community and its leaders can vote on projects affecting the vital resources that sustain their way of life.

On February 23, 2017, Chinda residents and municipal officials held an open town hall meeting in which they voted to keep hydroelectric projects out of the municipality. However, the dam project never stopped, and project representatives claimed that they were well received at the meetings held with the affected neighborhood councils. There is no documentation of these meetings in the project records maintained by the Ministry of Natural Resources and the Environment (Secretaría de Recursos Naturales y Ambiente – MiAmbiente).

“The town hall meetings don’t work, but it’s all we have because the prior, free and informed consultations are no longer required. And they won’t work if they only hold these meetings when it suits them. Sometimes they are useful. I think that the meetings were useful for Chinda because certain things have been suspended,” said Vásquez.

Although the dam representatives claim that they haven’t encountered any community opposition, Vásquez says approximately 100 people have publicly demonstrated against the dam project.

According to Chinda resident and MAS member Manuel Medina, they began protesting the dam in 2018 when they saw construction machinery on the dam site. Medina said, “They showed us documents to prove that they had the necessary permits, which is when we realized that the dam was being built 12 kilometers from the border with Cortés department, between the municipalities of Villanueva and San Antonio. These are the only two municipalities that are going to receive monthly payments of US$8,000 for 15 years, so Chinda won’t receive any payments. This is why we started protesting the dam. We held two sit-ins on the suspension bridge over the Ulua River that were broken up by the police.”

Rosmery is another MAS member from Chinda. She’s a young industrial engineer who graduated from the National Autonomous University of Honduras and, like many other young people, can’t find a job in the area.

“They promised us that Chinda would be the next Venice, and that we will have opportunities to get ahead in life, to build hotels. But we’re a very poor community and only two families might have the means to build a hotel. We’re defending our municipality because it will be most impacted [by the dam]. Other places will benefit but won’t be flooded [by the reservoir] like us,” said Rosmery.

MAS members claim that the dam will ruin one of their community’s most important cultural events; the freshwater “sardines” that spawn in a place called La Sardinera, a 40-minute walk from town. They catch the small fish as they jump out of the river and later make a meal out of them. Gallegos, Hidrovolcán’s public relations manager, says that the sardines aren’t going to disappear, but that she doesn’t know how the dam will affect access to that area. She claims that they have nothing to do with La Sardinera.

The people of Chinda claim that there are no job opportunities there; only subsistence agriculture and open-pit mining of river sand to sell. According to data collected by MAS, 70% of Chinda residents live in poverty.

However, according to Hidrovolcán, the flooding from the dam reservoir isn’t a threat to Chinda, but will instead provide opportunities they never had before. Gallegos says, “We call it the Venice of Honduras because the reservoir will turn the area into a tourist destination. The river is just a puddle right now, but the dam will raise the water level enough for boat use and people can come to Chinda for a walk by the riverside.” She repeats that it will be an opportunity for Chinda, and that its people should think about building “small hotels.”

Gallegos also says that dam construction will generate approximately 3,000 temporary jobs for people in the area, but that they won’t be able to solve all the problems caused by long-standing government neglect, as it’s not the company’s role to replace the government.

Despite the company’s apparent lack of concern about opposition from Chinda’s indigenous population, Betty Vásquez believes their activism is risky.

“I don’t want my face on T-shirts and banners. My children tell me that they’re afraid because of what happened to Berta and Margarita Murillo. I tell them that this won’t happen to me because I go about things quietly. I don’t want to be a hero, but I’m not afraid either,” says Vásquez, who was a friend of Berta Cáceres, a supporter of MAS since its creation in 2011.

After the smear campaign launched by journalist Edward Fernandez following the November floods in the Sula Valley, Vásquez filed a formal complaint against him and eventually accepted his public apology.

At the conclusion of the complaint hearing, Vásquez’s lawyer, Kenia Oliva, said, “It’s important that our society hold these people accountable so that our institutions can function properly, and so people don’t feel so vulnerable even when their communities are so underprivileged.”

Manuel Zelaya, the dams and Odebrecht

Regarding the Los Llanitos and Jicatuyo dams also considered a priority by the current government, former president Manuel Zelaya (deposed in the 2009 coup d’état) stated on Twitter that his administration approved both projects as well as their funding, but that the coup perpetrators had rescinded the agreements. Memorandum 457-2016 of the Special Unit for Renewable Energy Projects indicates that the projects weren’t cancelled until several years after Zelaya’s administration ended. This document describes how in 2013, the Los Llanitos dam was approved, modified and then suspended by the same company contracted to implement the project.

The Los Llanitos dam was first described in a 1979 study of the Ulúa River’s hydroelectric potential. It took its first solid step forward when the Zelaya administration declared an emergency for the nation’s electricity system through executive order PCM 04-2006. This authorized the ENEE to bypass the normal bidding process and use the BOT (Build, Operate and Transfer) direct contracting process. The BOT mode designates a private company to build and operate an electricity generation facility, and to then execute a no-cost transfer of the facility to the government. This is the same model used for large infrastructure projects such as the country’s toll roads for freight transportation and tourist travel.

On January 6, 2009, the Zelaya government declared the emergency in the electricity system, which enabled the ENEE’s special intervention board chaired by Rixy Moncada to sign agreement 01-JI-61-2009 a few weeks later with Norberto Odebrecht, a Brazilian construction company. This company was at the center of a 2016 corruption scandal when, according to the U.S. Department of Justice, it paid almost $800 million in illegal kickbacks for more than 100 public works projects in 11 Latin American countries, Angola and Mozambique.

The ENEE memorandum states that after significant progress in the dam’s design and socio-environmental management, work stopped in 2012. According to file 39-E-2003, which contains all the information on the Los Llanitos hydroelectric project (118 megawatts of installed power), the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment claims it was never able to obtain a copy of the Odebrecht contract signed by the Zelaya administration, and that the company never produced a feasibility study of the project during its four years of operation in Honduras.

Between 2009 and 2013, at least two contract modifications were approved by the Michelletti and Lobo administrations to allow more time to produce the agreed studies. The contract was finally terminated because the government failed to allocate US$100 million to the project in December 2012.

In 2018, the MACCIH (Support Mission Against Corruption and Impunity) anti-corruption mission sponsored by the Organization of American States announced that it was conducting an investigation of six Honduran former government officials to determine if they had participated in the corruption network that bribed public officials throughout Latin America to approve construction contracts for Odebrecht. The investigation faded away after MACCIH was shut down by the Honduran government at the end of 2019.

Contracorriente requested an interview with former President Zelaya to clarify the contracting processes used in this case, but did not receive a response.

Chinda’s abandonment

Right in front of the shelter for the Chinda flood victims, houses are being built for five families that had closed deals with the El Tornillito dam builder before the floods. This has caused more concern in the community, as well as some internal conflict. But everyone seems to agree that the dam could improve working and living conditions for the community.

“The dam is moving forward no matter what. No one can change that, except maybe a miracle from God,” said Maria. She thinks that opposing the construction is pointless because they don’t have the power to stop such a big project. All they can do is demand dignified treatment.

“We need land to build our new homes. There have been grants to build houses, but we don’t have the land. We can’t just abandon our properties because it’s all we have right now. If they’re interested in our land, then they have to buy it just like they did for the others,” said Maria.

Visibly upset, Maria said, “We have accepted our loss because it was a force of nature. Everything that happens is allowed by God, and we know that He will bless us with a house like we had before.”

While María discusses with other villagers what the company has said to them, her daughters play around the ruins of their house. Her eldest daughter climbs a wall partly demolished by the storms, and looks at the river about 500 meters away, listening to its sound. They haven’t gone to swim or wash in the river since the disaster, and only hope that someone will help them so they don’t have to experience another one.