One of the pandemic relief measures taken by the government of Honduras was to secure up to US$2.5 billion in debt to be used for guaranteed loans channeled through a government bank to small and medium-size enterprises. Despite the government’s promises of relief for small businesses, our investigation found that this money has mostly benefited private banks, business conglomerates, and medium-size companies. There has been almost no official relief for microenterprises.

By: Fernando Silva

Illustrations by Miguel Méndez

Photos by Martín Cálix

De La Montaña Café is a microenterprise that sells various types of coffee. The business had been steadily growing, and grew even more quickly when it opened a small shop in a Tegucigalpa office building in 2017. The owner, Monserrath Morazán, was pleased with her progress – she had won several tasting competitions and now had four employees.

The pandemic brought all that to an abrupt end. She had to close the store on March 16 after the government decreed a state of emergency and quarantine to contain the virus outbreak. But she had to keep paying rent, and without any income, she soon went into debt. In July, the micro-entrepreneur gave up her lease on the office building space, dismissed three employees, and started working from home. Some of her clients continued to buy coffee beans and ground coffee, but sales dropped to a third of pre-pandemic levels. This was only enough to make payments on bank loans.

“We have been completely abandoned,” said Monserrath in a phone interview with Contracorriente. “Every day we do what we can with what we have, but no one has stepped up to help.”

By April, almost four out of ten micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) had temporarily closed down.

Loans were available – but for whom?

President Juan Orlando Hernandez said on August 16 that, “The global economy, including the Honduran economy, has been seriously affected. But micro and small enterprises have suffered the most … we all have to take action to support them.” This has been the rhetoric coming from the government since April. Accordingly, most of the growth in Honduras’ public debt has been focused on providing financial relief to businesses and workers. The nation has raised US$1.05 billion by issuing government bonds and obtaining loans from nine multilateral organizations, according to the Ministry of Finance’s financial plan to address the COVID-19 pandemic impacts.

According to the Honduran Private Enterprise Council (Consejo Hondureño de la Empresa Privada – COHEP), the 300,000 MSMEs like De La Montaña Café generate 70-80% of the country’s jobs and about 25% of Honduras’ gross domestic product. As such, it’s to be expected that MSMEs would be a priority focus for the pandemic assistance effort.

However, our investigation reveals a very different story. Contracorriente was part of the international Following the COVID-19 Money investigation that included Guatemala’s Guateleaks alliance, Costa Rica’s Channel 13 News, and the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística – CLIP).

The Honduran state bank for production and housing (Banco Hondureño para la Producción y la Vivienda – BANHPROVI) operates as a first-floor and second-floor lender that places rediscounted funds with private banks for lending to end users. BANHPROVI has underwritten loans for production support programs and MSMEs.

Economist Hugo Noé Pino describes rediscounting as a mechanism in which “banks lend out their own money, but then BANHPROVI repays them the full amount of the monies lent… the private banks are only intermediaries for delivering financing to the end users.”

“BANHPROVI is allowed to lend directly to private banks, but if the loans issued by this state bank are not carefully monitored, there is a high risk that loan defaults could soar and possibly bankrupt BANHPROVI.”

Contracorriente requested a list of the 100 largest BANHPROVI loans granted to entrepreneurs under this mechanism between March 27 and October 20, and found that the largest pandemic-relief loan was made to Grupo Jaremar, which produces a quarter of the country’s African palm oil on 1,500 hectares of land in the Bajo Aguán region.

This conglomerate obtained 80 million lempiras (US$3.3 million) through seven loan applications for various purposes, including the purchase of a work vehicle and the cultivation of African palm oil trees in an area embroiled in a long-running land dispute that has intensified over the last 10 years.

Another large loan amounting to 28 million lempiras (US$1.1 million) was obtained by Compañía Azucarera Tres Valles for biomass energy generation.

The 100 largest loans amounted to 1.78 billion lempiras (US$72.8 million), distributed as follows: 1.05 billion lempiras (US$42.8 million) for production loans (agribusiness, palm oil, renewable energy, hotel sector, agricultural machinery); and 735 million lempiras (US$30 million) for loans to the MSME sector.

One recipient of a smaller loan is Asterio Reyes Hernández, a National Party leader, former president of the Honduran Coffee Institute (Instituto Hondureño del Café – IHCAFE), and father of Samuel Reyes, the former defense minister during the current president’s first term.

Pino explains that these rediscounted loans “have almost always been granted to medium and large businesses. They hardly ever go to small businesses. The loans are granted to African palm oil producers, many of whom own very large plantations, and to large producers of basic grains. Small farmers are never beneficiaries of these loans.”

Large businesses are not the only ones who are benefitting from these loans – private banks are also doing well. The annual interest rate charged by BANHPROVI to the financial intermediaries (private banks) never exceeds 4%, but the private banks are allowed to charge borrowers up to 13% in annual interest. The difference between the private banks’ borrowing and lending rates represents their profit margin.

Ficohsa Bank was the biggest lender in this program, granting loans amounting to 272.9 million lempiras (US$11 million) that were later reimbursed by the state bank (rediscount). It profits from the difference between the low interest rate offered by BANHPROVI and the higher interest rate it charges its clients.

The emergency assistance law does not benefit everyone

Another emergency assistance measure by the government to help medium and small businesses that had to close down due to the mandatory lockdown was the Law to Provide Pandemic Relief to the Productive Sector and Workers, approved by the National Congress at the end of April 2020.

Implementation of this law was funded by a US$200 million joint loan from the Honduran Central Bank (Banco Central de Honduras – BCH) and the Central American Bank for Economic Integration (CABEI). CABEI’s action plan for its COVID-19 Emergency Assistance and Preparedness Program and overall economic stimulus was used to guide its lending to several Central American countries, including Honduras.

The BCH used the CABEI loan to create two trusts within BANHPROVI to manage two guaranteed loan funds. One fund was for large companies (about 950 companies nationwide), and amounted to 1.9 billion lempiras (US$77 million). The second fund was for the MSME sector, and amounted to 2.5 billion lempiras (US$102 million).

The way this mechanism works is that the BANHPROVI issues collateral guarantees for the business owners who use them to secure loans from private banks. MSMEs (the target sector for this program) usually only need collateral (mortgages, fixed assets, or fiduciary instruments) of 10-35% of the loan amount.

According to Hugo Noé Pino, “If the borrower doesn’t pay off the loan, then BANHPROVI has to pay the risk assumed by the bank, which in this case, could be up to 90% of the loan amount.”

On April 24, President Juan Orlando Hernandez made statements on television and radio touting this loan program as “the oxygen” that MSMEs need in order to stay alive during the pandemic. “The vast majority of the country’s borrowers are micro, small and medium-size businesses,” said President Hernandez. “Well, now 90% of their bank loans will be guaranteed by the government so that they can easily obtain the credit they need from banks, cooperatives and finance companies.”

To understand who was benefiting from this government-backed loan program. Contracorriente submitted a public information request for the list of loan guarantees issued by BANHPROVI from the MSME and large company funds.

The two BANHPROVI lists do not include the borrowers’ names, so the type of company receiving the government guarantee could not be determined. The MSME fund issued 50 guarantees amounting to 122.7 million lempiras (US$5 million), while the large company fund issued 15 guarantees between April 24 and October 29, amounting to 196.1 million lempiras (US$8 million). Clearly, the total value of the loan guarantees issued to large companies is higher than those issued to MSMEs.

In our telephone interview, De La Montaña Café owner Monserrath Morazán (who has no outstanding debt) said, “Remember that the government said it would guarantee 80% of these loans? I talked to BAC and Banco Atlántida, but they didn’t say anything about an 80% guarantee or any guarantee at all. Instead, they told me I’d have to put up collateral representing 70% of the loan amount. I can’t risk all that if I don’t know what the future holds.”

Esperanza Escobar, president of the National Association of Small and Medium Industries of Honduras (Asociación Nacional de Medianas y Pequeñas Industrias de Honduras – ANMPIH), says that when the government claims to have secured credit for MSMEs, or that it has facilitated a certain amount of MSME exports, or that it has purchased millions in MSME products, they’re not really referring to MSMEs. “They’re helping the medium-size companies, which are actually just as stable as the large companies,” she said.

ANMPIH president Esperanza Escobar says that there may be trillions of lempiras in the bank for MSMEs, but they will never be able to access these funds because they can’t meet the private banks’ lending requirements.

According to Escobar, small businesses can’t meet the private banks’ lending requirements. “For example, banks ask us not to live in neighborhoods with social risk. But most small business owners do live in neighborhoods with social risk, so our properties are not valued by the banks – they don’t accept them as collateral. We don’t have other properties, just ourselves,” said Escobar.

Escobar thinks that the banks are ignoring this law. “The banks prefer to lend one million to a single, medium-size business over lending one million to ten micro and small businesses,” she says. But it’s the government’s responsibility to support and promote the economic sector that generates the most jobs.

Another problem confirmed by several sources is that MSMEs haven’t been able to access these guaranteed loans because most of them got into debt just to survive during the months of lockdown. The MSMEs have now been reported to the country’s central credit risk reporting agency.

“This type of government-guaranteed loan can be useful,” says Pino, “but microenterprises often can’t secure these loans because they already have outstanding debt.” Escobar agrees, saying “We can’t get money from the banks because of our credit reports.”

“The only way that private banks can lend to MSMEs is for the government to assume the risk, because the current crisis isn’t predictable,” said Mayra Falck, an economist and BANHPROVI’s executive president, in a Zoom meeting with Contracorriente. “The government issues the guarantees, telling the microenterprises not to worry, that it will cover 90% of a loan for 300,000 lempiras (approximately US$12,000) or less. However, for these microenterprises to obtain the guarantee, they have to be rated well by the private banks, not BANHPROVI. “The moral responsibility to repay the loans is the most important thing,” she says.

In short, microenterprises that cannot pay their debts due to the drop in sales brought about by the government-mandated shutdown are the types of businesses that most need the government’s loan guarantees in order to survive this crisis. But BANHPROVI will only provide the guarantee if private banks certify that the business has no existing debt. And since most do have existing debt, they do not qualify for this government assistance.

Economist Ricardo Castaneda, of the Central American Institute for Fiscal Studies (Instituto Centroamericano de Estudios Fiscales – ICEFI), told Contracorriente that it seems as if this guaranteed loan program was designed from the beginning to “exclude most of the micro and small businesses that weren’t going to qualify for these loans… The political rhetoric about protecting this sector is meaningless without the implementation of measures that can really make it happen.”

The Confianza Contract

BANHPROVI decided that it wasn’t going to directly provide the loan guarantees when it saw that it might have to manage 50,000 or more of them for small businesses. Instead, it decided to outsource the process to a private company owned by private banks.

Once the MSME trust account had been set up by BANHPROVI, Falck sent a public letter on May 27 to Mario Agüero Lacayo, executive vice president of Banco Atlántida, one of the country’s most prestigious private banks, and also president of the board of directors of Confianza Sociedad Administradora de Fondos de Garantía (Confianza SA-FGR). Agüero’s letter requested a financial and technical proposal to provide outsourced management services for the estimated 50,000 monthly MSME loan guarantees that BANHPROVI expected to issue.

According to public documents obtained by Contracorriente, Confianza is owned by three Honduran private banks: Banco de América Central (BAC), Banco Atlántida, and Banco Ficohsa.

According to public information from the National Commission for Banks and Insurance Companies (Comisión Nacional de Bancos y Seguros), Confianza has been authorized to issue loan guarantees and manage funds to facilitate access to credit, and is mainly responsible for issuing and delivering the loan guarantee certificates to businesses applying for loans from Honduran banks.

“To issue 50,000 monthly loan guarantees without having an adequate platform to do this was not a good fit for BANHPROVI. Confianza’s platform can more efficiently issue loan guarantees to intermediaries,” says Falck. Since there was only one supplier for this service, the Confianza contract was executed in accordance with the Government Contracting Law.

“There’s nothing to hide here, everything is on the [government] transparency website,” she said. However, when Contracorriente found that the final contract was not posted to the transparency website, we asked Falck about the contract terms. She replied that because Confianza is a private company, “it’s difficult for us as public officials to disclose private information.”

Nevertheless, Contracorriente was able to find out through an information request that the contract between BANHPROVI and Confianza has a term of 18 months, and that Confianza will be paid 9.2 million lempiras (US$375,553) for its services. In addition, Confianza does not assume any risk in issuing the loan guarantees, and is only required to submit semi-annual activity reports in order to receive the agreed upon payments.

ANMPIH’s president, Esperanza Escobar, questions the risk-free deal that Confianza made with BANHPROVI, contrasting it with the difficulties encountered by microbusiness owners seeking loan guarantees and loans during this crisis. She said, “We’re the only ones who can’t do business with the government. They’ve bailed out banks, businesses, and franchises, but what about us?”

No one was approved for a loan

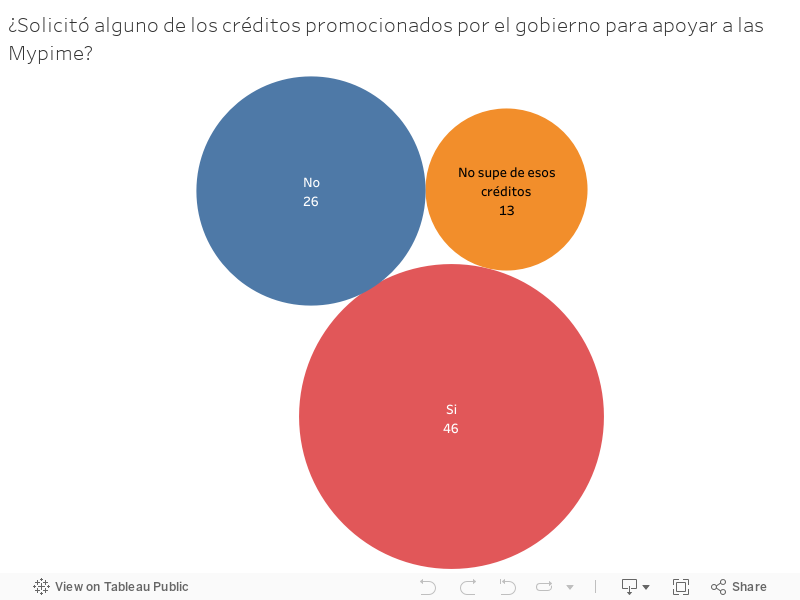

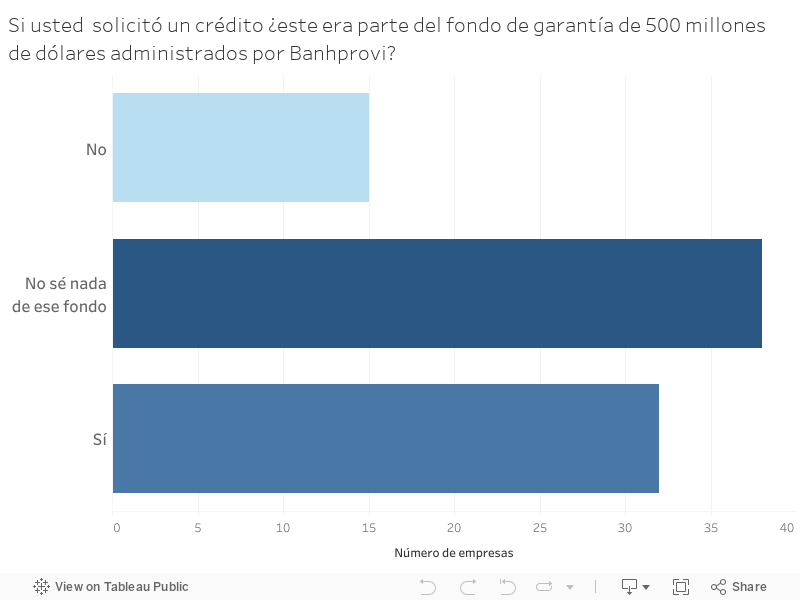

Contracorriente conducted a survey of 85 micro, small and medium enterprises associated with ANMPIH, and found that the vast majority of them had been profoundly affected by the pandemic. Yet no one had received any government assistance. More than half of those surveyed tried to obtain a guaranteed loan, but not a single one was approved.

Of the business surveyed, 55.3% identified themselves as microenterprise owners (1-10 employees), and 43.5% said they owned small businesses (11-50 employees). 81.2% of these businesses said their income had been significantly affected by the pandemic.

A little more than half of the businesses surveyed applied for the MSME guaranteed loan program, but none of their loan applications were accepted. Most of those who had already received formal notice of loan denials indicated that a bad credit history was cited as the reason.

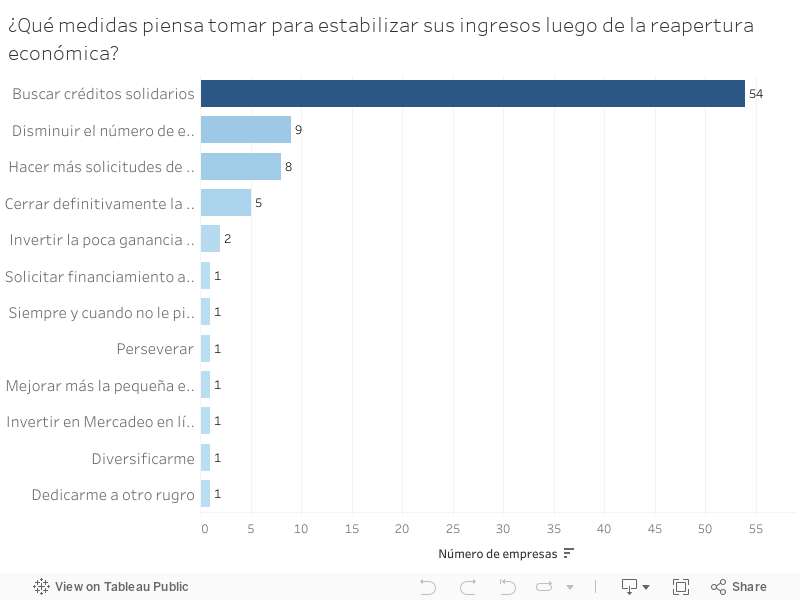

In light of the recent easing of pandemic-related restrictions, 9% of the businesses surveyed plan to continue submitting loan applications to the private banks, while 15.5% are deciding whether to dismiss employees or shut down altogether.

More than 60% of the businesses surveyed said they weren’t going to give up, and will apply for the new “solidarity” loans. These government loans theoretically don’t require borrowers to be completely debt-free, but this hasn’t been the case in practice.

Escobar says that they have asked the government to facilitate these solidarity loans because they have no other way to obtain the working capital they need to keep businesses that have been closed down by the pandemic afloat.

“The banks are awash in cash because they don’t lend to microenterprises – they don’t want to take risks,” says Escobar. “They want everything to be safe – good properties and good collateral. They want the borrowers to demonstrate that they are earning big salaries, but this is a poor country. If there is no money to put poor people like us to work, then what?”

Doubts about the new solidarity plan

Ignoring the views of experts cited in this article that the flawed designs of government relief mechanisms have made it almost impossible for micro-businesses to access this assistance, President Hernandez held a press conference on August 17 and blamed the banks.

“Many micro-business owners have said to me, “Mr. President, loan guarantee funds may have already been created, but they’re useless to us and we’re drowning here. The banks charge us interest on top of interest, our credit scores drop, and then we don’t qualify for loan guarantees,” exhorted the president.

He then introduced a draft bill for a new Plan for Financial Support and Solidarity (Plan Financiero de Rescate Solidario). The objective of this new plan was to lower interest rates on loans to stimulate production and employment. Also, the banks were not allowed to charge delinquent loan fees, service fees, or any other additional costs.

Many businesspeople say that this bill puts the national financial system at risk. Pedro Barquero, president of the Cortés Chamber of Industry and Commerce (Cámara de Industria y Comercio de Cortés – CCIC), is not very optimistic. “As long as we lack a competitive tax policy and an administrative simplification program, no investment projects will be willing to raise capital through the available debt mechanisms under current conditions,” he said.

While the draft bill remains stuck in the National Congress, the government signed an agreement on October 18 with the Honduran Association of Banking Institutions (Asociación Hondureña de Instituciones Bancarias – AHIBA) that theoretically obliges Honduras’ 15 private banks to restructure the MSME loans, extend the loan payback periods, and reduce interest rates by up to 2%.

Presidential Minister Ebal Diaz said that these loans will be for “everyone, with no exceptions. No one applying for these loans at a bank branch should be told that they know nothing about the government’s agreement with the bank presidents.” He reiterated that the banks committed to implementing the changes to the MSME guaranteed loan program immediately. But according to information received by Esperanza Escobar from ANMPIH members over the last few weeks, the banks are ignoring the agreement, claim to know nothing about it, and are only offering loans under normal lending conditions. “They aren’t even acknowledging the loan guarantees issued by Confianza,” says Escobar.

Even if these businesses could get the MSME loans with lenient terms, economist Ricardo Castaneda says that they will no longer solve the problems faced by these businesses. He says that since many of these businesses are on the verge of bankruptcy, a loan will not be enough to revive them. “They may need direct subsidies, or other measures such as guaranteed government purchases from micro and small businesses.”

Honduras’ public debt could reach 59% by the end of 2020, and rise to 60.3% of GDP next year. This means that for every 100 lempiras produced in Honduras, 60.30 lempiras are owed in public debt.

Castaneda and others worry that Honduras is getting so deep into debt in order to address the pandemic crisis, but the money is still not getting to the businesses that generate the most jobs. On the contrary, the data show that banks and big business have benefitted the most from the almost US$1 billion in public debt raised by the government to fund the COVID-19 emergency measures. Moreover, Castaneda says that the government has new plans to give additional tax exemptions to large companies.

The public debt acquired over the last 10 years has not improved Hondurans’ quality of life, says businessperson Pedro Barquero. “Our past history tells us that the new debt acquired to finance the pandemic emergency measures will just be more of the same.”

Tropical Storm Eta tore through the country, putting the brakes on the economic reopening that businesses desperately needed. This created a new opportunity for the government to take on more debt from international financial institutions. Marco Midence, the finance minister, submitted a request to the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) for an advance disbursement of US$35 million from the Green Climate Fund granted to Honduras in December 2019. These funds were to be used for the reforestation of pine forests devastated by pine bark beetle outbreaks.

In addition, the National Congress approved the use of 50 million lempiras (US$2 million) from the pandemic budget for storm damage repairs, and indicated that this money could be sourced from the US$2.5 billion in public debt authorized for the COVID-19 emergency.

***

Monserrat barely has time to talk with us, as she’s busy all day long making coffee deliveries by herself and baking. She doesn’t have much time for interviews, often answering our questions before we even finish asking them. She says that she saved her business by paying off all her debts.

“They [the government] only look out for the jobs generated by large companies. They worry more about them instead of us, maybe because our modest sales don’t produce much for them,” says Monserrat, who doesn’t know that small businesses like her own generate most of the country’s jobs.

To read the complete serie enter here: https://www.elclip.org/