Parts of the protected forest reserve of La Tigra National Park in central Honduras have been cleared to grow produce for Tegucigalpa’s dinner tables. Cabbage has become the economic mainstay of a community that settled in the wrong place.

By Fernando Silva

Photos by Ezequiel Sánchez

With his dog Canelo by his side, 55-year-old Patricio Colindres walks through a field blanketed with cabbage near his house in the community of Montaña Grande. The Colindres family has farmed here for three generations. Patricio wears rubber boots, muddy pants and a cap to shade his face. The sun is burning hot, even in the middle of a nature reserve that sits 1,700 meters above sea level.

As we exchange greetings, the burly, soft-spoken Colindres moves through a plot of purple cabbage; a different variety than usually seen in these mountain fields. The cabbage leaves rustle as he walks past. He stops and bends over to pluck a cabbage head from the soil.

“We’ve been growing cabbage ever since I was born,” he says, looking out at the fruits of many weeks of work. But back when his father was teaching him about the family business, they never raised purple cabbage. Fancy cabbage, he calls it, because it’s a high quality cabbage that fetches a higher price in the city. “I call it fancy because the color is just decorative; poor people don’t buy it.”

Colindres supplies cabbage to one of the most well-known supermarkets in the country. He sells four-pound heads of green cabbage wholesale for US$0.50, and the supermarket retails it for US$1.35. However, the wholesale price for the same size purple cabbage is US$1.35, and the supermarket retails it for up to US$5.05. Colindres says that a hectare (about 2.5 acres) can yield up to 32,000 heads of cabbage, which he distributes to urban and rural markets.

Colindres and his brothers own about 18 hectares of land planted with mostly green cabbage and some purple cabbage. They share profits among themselves and employ almost the entire community in their farming business.

But neither the man, the crop, nor the dog should be living in the core zone of La Tigra National Park ⎻ the country’s first nature preserve. La Tigra was declared a nature preserve by the Honduran government on July 14, 1980 in order to protect the cloud forest that sits high above the capital city, providing it and the surrounding communities with clean air and water. It’s also a large conservation area for various animal and plant species. But a farming community had been there long before the National Congress established the national park.

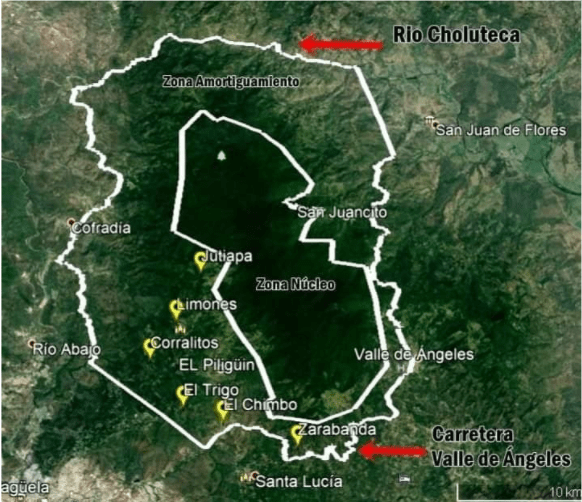

The protected area encompasses more than 24,000 hectares of forest in the country’s central mountain range, and is divided into a buffer zone and a core zone. La Tigra’s mountain springs supply about 25% of the water used by the Central District (Tegucigalpa and Comayagüela) in the valley below, about 12 kilometers from the park.

In 2019 and 2020, despite its abundant natural resources, the country suffered its worst drought of the last decade. At times, some communities were only supplied with water every 25 to 30 days. The La Tigra watershed was also unable to alleviate the crisis, so most people resorted to buying water from tanker trucks that filled up from city wells. The drought only added more misery to people trying to keep their food and households clean in the midst of a pandemic. The Water for People organization says that 49% of rural Hondurans don’t have access to clean water and proper sanitation.

La Tigra is a very important water source for the four municipalities that it spans: the Central District, Cantarranas, Santa Lucía, and Valle de Angeles. The latter two are small, but growing colonial towns that have become places to escape the capital city noise and congestion. Many of the restaurants, diners, and recreation areas in Santa Lucia and Valle de Angeles are located inside the park’s buffer zone, and housing development projects have boomed as more capital residents flee the city to live closer to nature.

The turnoff to Montaña Grande branches off the road to Santa Lucia. From there, it’s a 20-minute drive in a four-wheel drive vehicle that is able to navigate the narrow and rugged road. The other option is an arduous two-hour hike up a trail that climbs 500 meters into the mountains. This community is located in La Tigra’s core zone; the focus of efforts to restore the forest through natural regeneration or assisted reforestation. The objective is to restore land that has been harmed by human activity, fire and insect infestations.

Developed by the Forest Conservation Institute (Instituto de Conservación Forestal – ICF), the park’s 2013-2025 management plan notes that, “The forest has been cut down for farming activity, causing soil erosion and water contamination from fertilizer and pesticide use.” The management plan aims to restore the cloud forest and limit agricultural activity like the Colindres cabbage farms, as much as possible.

Colindres says his family has lived there since the early 20th century, and slowly transitioned from subsistence farmers to selling their crops. They first tried carrots, but when that didn’t pan out, they tried cabbage and saw that they could have hundreds of pounds ready to sell in only two months. The entire extended family began raising cabbage. Nowadays, this is the only crop to be seen in some parts of Montaña Grande.

According to 2019 data from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Honduras produces almost 95,000 tons of cabbage and cruciferous vegetables. This makes it the eleventh largest crop in the country, bigger than some basic staples like bananas. The FAO data indicates that most of the country’s cabbage crop is consumed domestically and little is exported.

Colindres grows the Greenboy, Royal Vantage, Escazú and Cairo varieties of cabbage. Supermarket managers usually only come once a month to pick up the durable produce, and buy about 1,500 heads of the roughly 5,000 heads harvested every month. “All this will turn green in about a month,” says Colindres, pointing to two workers planting cabbage seed in a field that used to be forest. He notes the need to always have his product ready for the unpredictable supermarket buyers.

Too numerous to count, cabbage heads fill fields that should be forested with pines and other tree species. Colindres denies that his cabbage fields lie within the national park’s core zone, and says that even if the government were to buy his land, he couldn’t live anywhere else. “How can we find what we have here anywhere else?” he asks.

Justo Zapata, one of the few residents who disapproves of farming in the protected zone says that maps clearly reveal the damage done by the farming in the La Tigra National Park.

“We’ve had lots of meetings about this,” says Zapata. “These farmers know that they’re inside the park’s core zone.” Zapata is a 48-year-old native of Montaña Grande, and one of the few who doesn’t work on the cabbage farms. Instead, he works as the resident technician for the Eden Reforestation Projects in Honduras, an effort to reforest 250 hectares of the park’s core and buffer zones.

“It’s a huge shock to see this and wonder, ‘My God, is this really happening here? It can’t be,” says Zapata. He believes that reforestation is important and the only way to preserve La Tigra for the future. “It’s hard for these local communities to change for the better. The forest will continue to disappear, so all we can do is hold on, hold on, hold on.”

Governmental inaction fails to protect La Tigra

“You can’t require more from the farmers. In an ideal world, buyers would pay higher prices [for produce], and some of that money could be used for improving agricultural practices. That’s a potential strategy, but you can’t really ask this of the farmers right now,” says Alejandra Reyes, who heads the ICF’s protected areas department.

Regarding the supermarkets that indirectly impact La Tigra by buying cabbage grown in the core zone, Reyes says that the government has been unsuccessful in establishing conservation agreements with private enterprise. There is no environmental awareness, regulation, or law that obliges them to restore or minimize any damage they might cause.

Jorge Palma, technical director of the Friends of La Tigra Foundation (Fundación Amigos de la Tigra – Amitigra), says that ever since the park was designated a protected area, Amitigra has worked with the existing communities on environmentally friendly practices, and has also monitored the agrochemicals they use.

“Making this cultural change from using harsh, fast-working agrochemicals to introducing organic farming processes is almost impossible, especially since all this is linked to market behavior. For example, the domestic market isn’t interested in paying more for high-quality products that require a little more work. Buyers say, ‘I’d rather buy this tomato that was sprayed with glyphosate herbicide and who knows what else because it costs eight cents, instead of that organic tomato that causes less damage but is smaller and costs more than twice as much,’” Palma says.

The two largest and most popular supermarket chains in Honduras are Walmart and the Honduran company, La Colonia. Both market themselves to consumers as supporters of small, local farmers, but this is usually limited to helping them with crop diversification and financing. Most consumers don’t know where their fruit and vegetables come from, or whether they are damaging protected areas like the cabbage farms in La Tigra.

Palma points out that although farmers in Montaña Grande usually make enough to live on, sometimes they lose almost everything. This happened in 2020 during the pandemic when mobility restrictions prevented them from selling their product.

Despite all the obstacles, Palma hopes to implement an Amitigra certification process for produce grown in the park using environmentally friendly practices in order to raise awareness among buyers and motivate farmers to change.

Every organization involved with La Tigra is very concerned about its problems, especially the core zone. And this concern is not limited to La Tigra, says Byron Mejía, technical coordinator of the Eden Reforestation Projects and Justo Zapata’s supervisor. Mejía says that none of the country’s 73 protected areas adequately prevents agricultural and human encroachment.

A public information request for ICF data revealed that five protected areas have active hydroelectric or mining concessions, nine have illegal African palm or coffee plantations, ten have reports or ongoing investigations about construction, forest clearing, farming or forest fires, and five have housing developments, hydroelectric projects or Employment and Economic Development Zones (Zonas de Empleo y Desarrollo Económico – ZEDE).

In August, Christopher Castillo, the coordinator for ARCAH (Alternativa de Reivindicación Comunitaria y Ambientalista de Honduras – ARCAH), a community and environmental activist group, alerted local media about a move to establish a ZEDE in La Tigra. The ZEDE mechanism grants investors sovereignty over a specific area of Honduran territory and allows them to establish their own security force, conflict resolution procedures, and fiscal policy. The only Honduran laws that apply to a ZEDE are the country’s constitution and penal code.

In response, the Amitigra board of directors released a statement that noted how the ZEDE law jeopardizes a number of other Honduran laws and imperils “environmental safeguards.” The Amitigra statement declared its opposition to any economic model that does not protect natural resources and water sources.

“The tree cover in these areas is crucial because it traps moisture from the clouds. Without trees, water doesn’t filter down to the ground, which depletes the water available to the surrounding communities. People only see a deforested area, but they don’t think about the other problem ⎻ the water source,” says Mejía.

Mejía thinks that there should be more focus on reducing population growth in the Montaña Grande area by preventing people from migrating to the core zone, “New generations will need housing, food and water, of course. But there won’t be any water when they grow up because there will be other families with the same needs.” The Eden Reforestation Projects’ strategy of creating forest restoration jobs has led former cabbage farmers to use a number of techniques to reforest the damaged areas of La Tigra.

Action by the central government has been late in coming and usually goes no further than public statements. On May 18, President Juan Orlando Hernández participated in the signing of an Inter-Institutional Agreement to Develop a Joint Process for the Sustainable and Responsive Management of La Tigra National Park. Mejia and other conservation organizations fear that this plan will never be implemented and that the national park will be further deforested as people fleeing the bustle of the capital city settle in the area thanks to acquiescence from local municipal governments.

Cabbage fields in an area of La Tigra National Park’s core zone where there are no pines, sweetgum or other native trees due to bark beetle infestations, forest fires, or illegal logging. Tegucigalpa, April 24, 2021. Photo by Ezequiel Sánchez.

Urban sprawl threatens La Tigra

Up the trail towards Montaña Grande, about 500 meters after the last house in the buffer zone, a sign nailed to a tree reads, “Fences, houses and farming are forbidden.” It was put there by Amitigra, an organization that is doing all it can to reduce the impact of human activity.

Palma has been working for Amitigra for 10 years and says urban development within the park has grown at an unprecedented rate over the last four years.

“Land sales here have increased over these two pandemic years,” he says. “More and more people have bought land here and are now showing up wanting to build inside the park. I get five to ten calls a day from people asking me about properties in villages within the protected zone like El Piligüin, El Chimbo, and Las Golondrinas. They tell me that they own land and need an environmental certification from Amitigra, he adds.

In April 2021 alone, 92 environmental certification requests were submitted to Amitigra. Before 2019, only 60-65 such requests were received all year. The requests range from permits to cut down trees from people who live inside the park, to inquiries about whether a property lies within the buffer or core zones. Palma says that some people act responsibly and don’t pursue a land purchase once they learn that it’s inside park boundaries, “But others ask for the management plan so that their lawyers can find loopholes that will allow them to build within the protected area. In most cases, the municipalities end up granting the building permits.”

La Tigra’s management plan prohibits new human habitation of any kind (subdivisions and urbanizations) in the protected area. Only “organic growth of existing settlements” is permitted. The municipal governments fail to comply with this guideline when they allow people from outside their communities to settle in the area. While the Central District has municipal jurisdiction of over 75% of the park area, Palma notes that it never got involved in conservation issues until about four years ago.

“To them, this was always a deserted area, so they focused on the city. In the past, local community rules governed this area, but when we tell local residents now that they have to apply for permits at the Central District municipal office, it’s a problem. They ask, ‘But why ⎻ they’ve never done anything for us.’ Also, the permitting process is expensive and many local people don’t have the money.”

One of the main conservation-related conflicts with the Central District municipal office has been the Bosques de Santa María residential housing development, approved by the Ministry of the Environment and the mayor, Nasry Asfura. He claims that the project was approved due to the need for 150,000 more homes in the municipality.

The real estate development project covers a 500-hectare area and is aimed atTegucigalpa’s well-off elite. It includes 2,300 homes, an education center, shopping centers and stores, a riding club, a church, a fire station, an artificial lake for water sports, as well as protected forest areas, recreation and leisure areas.

According to the developer’s website, the project will “have it’s own drinking water system, sewage treatment plant, irrigation system, and fire station. The development will be environmentally friendly, use solar energy, and treat its own wastewater.”

In an interview with a Honduran news outlet, the developer’s representative, Guy Pierrefeu said, “Early on in the project, SANAA [the water and sewer public utility] told us that it would not be able to supply water for this housing development. Our solution was to drill wells that are 1,070 meters above sea level and several kilometers below the surface of La Tigra, so we don’t affect the area.”

The developers say that the project will be developed in three stages over a 20-year period, with an initial investment of US$53.7 million. The project site covers almost 500 hectares, 96 of which are located within the buffer zone of La Tigra National Park.

Publicity surrounding this project brought the problem of human encroachment in the park to the forefront, and in September 2019, local residents demonstrated against the project, concerned about excess demand for water by the new residences. The demonstrations were suppressed by the National Police who used tear gas to disperse the crowd.

In light of the uproar, the Central District municipality halted the project, and Ministry of Justice prosecutors seized the documents that authorized the project. Mayor Nasry Asfura, now a presidential candidate, announced a public town hall meeting to obtain citizen input, but it never happened.

Palma says that he’d rather oppose further construction in the park zones that already have some development instead of focusing on the Santa María development’s 96 hectares within the buffer zone. This is a more immediate threat to the park’s buffer and core zones because property owners continue to sell land indiscriminately, and harm the natural preserve with slash-and-burn farming and logging.

In May alone, Amitigra’s Facebook page reported five forest fires in the park. Palma notes that human activity is responsible for most of these fires. Amitigra has documented an annual loss of 1,000 hectares of forest destruction from fire. Since 2015, 12.5% of Honduran forest area has been destroyed by blight, forest fires, land use change and illegal logging.

The long history of cabbage

The first record of cabbage cultivation dates back to the Egyptians, 2,500 B.C. The Greeks and Romans also grew cabbage, as it was thought to be good for digestion and hangovers. The Roman Empire popularized cabbage consumption throughout the Mediterranean basin, and it became even more widespread in the Middle Ages. By the 16th century, it was consumed in England and France, and it spread to the Americas in the 17th century during the colonial period. Nowadays, it is one of the most widely consumed vegetables in the world’s temperate zones. According to the FAO, China is the world’s largest producer of cabbage, with more than 33 million tons per year.

Coleslaw is an essential side dish for traditional Honduran meals and snacks, as it’s easy to make and store, and doesn’t spoil easily. It’s usually served with salty fried plantain chips, fried corn patties filled with potato and ground beef, pupusas (a thick, wheat-flour tortilla filled with cheese, beans or other ingredients), yucca with fried pork rinds, and other fried foods.

While cabbage continues to be very popular in Honduras, the country’s forests are not doing as well. According to an ICF report, 65% of the country was covered by cloud or dry forests 50 years ago. Now, an average of 23,000 hectares of forest are destroyed every year. According to Germanwatch’s Climate Risk Index (CRI), from 1998-2017, Honduras was the second most-heavily-affected country by hurricanes, storms and floods, making the forest destruction even more alarming.

***

Hundreds of people visit the park every weekend for ecotourism. Some go mountain biking, hike the trails, and swim in natural pools. In some ways, recreational use raises awareness of La Tigra’s importance, although the impact of human settlements in the area continues to be ignored. Almost no one knows about the cabbage farming, even though La Tigra is the last forested area that produces clean water for the Central District. No reservoir in central Honduras has better water than La Tigra.

It is also the only micro-watershed system in Honduras that does not have a dam or other water storage capability. When water first began flowing down the mountain to the surrounding communities, it was so plentiful and the population was such that no one imagined that a reservoir might be needed in the future. The droughts of the last few years have clearly proven otherwise. Building a reservoir is much more complicated because almost all of the viable area is now populated. Eighty percent of the protected area is owned privately by individuals who would have to be compensated and relocated before a reservoir could be built.

The La Tigra National Park also encompasses an old gold and silver mine that was operated by the New York and Rosario Mining Company from 1880 to 1954 in the community of El Rosario. The trails and paths used by the mine were integrated into the park system and are now used by tourists.

Amitigra has only received minimal local or central government support since its creation in 1993. In 2015, the central government even cut Amitigra’s funding.

The lack of government support continues even though a pine bark beetle infestation affected more than 500,000 hectares of forest nationwide from 2013-2017, according to government data. Some 5,000 hectares of La Tigra pine forest were destroyed by the infestation and are now scrubland.

Amitigra’s vision for the park is to maintain an island of forest for the conservation of flora and fauna that is also connected to other areas of biodiversity in order to allow wildlife like pumas and mountain tigers to migrate between La Tigra and other hunting and breeding grounds. The government’s lack of interest has prevented the development of ecological bridges between such areas, and has even discouraged some efforts that reduce human impact on La Tigra.

A potentially toxic cabbage

“What’ll you have ⎻ purple?” asks Patricio Colindres. Laughing, everyone takes a gift of “fancy” cabbage except for Justo Zapata, who declines, saying he hasn’t eaten cabbage in a long time. Zapata doesn’t eat cabbage even with pupusas. He says that if people knew what pesticides were being sprayed on the cabbage, they would stop buying it.

The cabbage grown in La Tigra is sprayed with Chlorfenapyr, an insecticide banned in the European Union. Studies have shown that it disrupts the endocrine system in the testicles and uterus, as well as being potentially carcinogenic. The use of this chemical in a protected area is even more dangerous considering that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has documented the biopersistence of the compound, as well as its toxic effects on bee, fish and bird reproduction.

Another herbicide used in cabbage farming is Paraquat, a chemical compound that has also been banned in the European Union, and has been compared to the dreaded Glyphosate distributed worldwide for years by Monsanto. Scientific studies have identified occupational exposure to this compound as a cause of Parkinson’s disease, and it’s considered highly dangerous as simple skin contact can cause serious digestive, kidney or lung problems. Even a small ingestion of Paraquat can kill an adult, and research indicates that it can increase the risk of Parkinson’s disease by 150% or more. Cases of Paraquat poisoning have been reported in Peru and Costa Rica.

Zapata says that another reason why he doesn’t eat cabbage is because of the damage it has caused in his community.

“This area was different three years ago,” he says. “Looking down towards Valle de Angeles, all you could see was forest. But now it’s all empty fields or farms. That shouldn’t be allowed.” In May, the organization that employs Zapata planted 30,000 trees in deforested areas of La Tigra National Park, and the goal is to reforest 250 hectares.

Zapata’s work has led him to think hard about his community, and he’s now convinced that the best thing to do is to relocate the community to prevent more uncontrolled expansion. “The work here is non-stop. Unfortunately, our community’s situation is a disaster. Nobody cares here, and nobody believes that our quality of life comes from the forest, water, and air. Nobody cares. The soil is being ruined by farming and deforestation. How do people in this community live? They don’t have electric or gas stoves, so they need firewood to cook. Where do they think the firewood comes from? From the forest. That’s why the problem just keeps getting worse,” he says.

Zapata explains that cabbage farming requires a lot of water. An average of 29,000 gallons of water is needed to irrigate two hectares of cabbage for three days. “Living here is beautiful. I always have water, and if I want to take five baths a day, I can. It’s wonderful ⎻ you can breathe fresh air. It’s also safer than the city ⎻ we sleep peacefully at night. When I was a teenager, all this was a beautiful forest, but now everything has turned gray,” he says wistfully.

Justo Zapata and Patricio Colindres can’t imagine living anywhere else. Standing at the edge of the deforested core zone where the cloud forest begins, Zapata points out his family’s properties and says that they have always tried to care for their environment.

As the sun sets over La Tigra National Park, its last rays wash over the cabbage farms and a large new house in the park’s core zone built by someone from the city. Outside is a barbecue grill and two small schnauzer dogs that bark furiously at passers-by.

Zapata says he would gladly move away if required, in the interest of conserving the park. He sees no reason to build new houses in the area. “People could live and work somewhere else, instead of damaging the forest here.”

Patricio Colindres says he’s willing to plant trees even though farming is his way of life and he doesn’t plan on changing. Some organizations have suggested this, and they’re willing to do it. He says it wouldn’t hurt to have lemon, orange, banana, and pine trees surrounding their fields. He acknowledges the need to replace chemicals with natural products and says that his family usually has a tomato and cabbage salad with their meals. “We can skip the tortillas and still feel full. If we want to fill up some more, we cook yucca with tomatoes and mix in some green and purple cabbage. But we don’t drink Coca Cola because it’s bad for us.”

This report was undertaken in collaboration with the Late Magazine School of Journalism.

Revista Late en el contexto de la Escuela de Reportería de Revista Late.