Photography by Martín Cálix and Deiby Yánes

Translation: John Turnure

Extreme poverty has always forced people to beg. This has been the story for years, reported in sometimes horrific detail. Countries like Honduras have never had government programs to help the poor overcome their financial and personal insecurity. According to Honduras’ national institute of statistics (Instituto Nacional de Estadística de Honduras – INE), 38.7% of the Honduran population was already living in extreme poverty in 2018 (the most recent data published on the INE website). When the COVID-19 pandemic hit the country, this poverty became more and more visible every day. The pandemic and the government’s response have imperiled the lives of thousands of people, many of whom have lost their source of income and are now living on the streets.

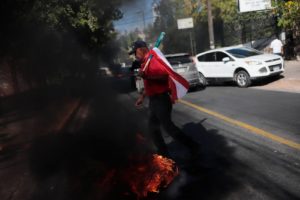

After the state of emergency was declared, the subsequent permanent curfew and stay-at-home order caught many people off guard. Thousands have been forced out onto city streets to beg for money, food, or anything that can help them deal with the virus outbreak in Honduras. A common sight in the streets of Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula were youths cleaning windshields for whatever the drivers wanted to give them. Others juggled to entertain passers-by, sometimes even juggling machetes and fireballs. But one never saw entire families and so many single mothers and children as now. The beltway road around Tegucigalpa is now lined with groups of people holding up signs with words of helplessness.

According to the Ministry of Labor and Social Security (Secretaría de Trabajo y de Seguridad Social – STSS), the open unemployment rate (people who want to work but cannot find a job) remained stable around 240,000 people in 2019, equivalent to 5.7% of the economically active population. But many people have lost their jobs during the pandemic, even though executive decree PCM 021-2020 was issued two weeks after the state of emergency was declared. This decree included measures by the Honduran government to prevent layoffs and secure jobs. Heartlessly disregarding the worldwide crisis, businesses furloughed their employees or “associates” (the latest jargon), making them count the time off as vacation days. Some workers have been pressured by their employers to return to work, in many cases with lower pay, while the country’s infection rates hit a peak.

But a large part of Honduras’ economically active population didn’t have formal jobs to begin with, and surviving from their informal work has become even more difficult. The plan to reopen the economy was doomed to failure, because it never incorporated the informal employment sector.

“As a result of the crisis prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic, the population living in extreme poverty in Latin America and the Caribbean could reach 83.4 million people in 2020, which would entail a significant rise in hunger levels due to the difficulties these people will face in accessing food”, stated a report, issued jointly on June 16 by the Economic Commission on Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO).

The once-crowded streets of Honduras’ main cities are now occupied by women, single mothers, and domestic workers who haven’t been able to return to work because their employers are afraid they’ll bring the virus with them. These women of all ages are forced to endure sexual harassment and insults from drivers who sometimes throw some money at them or threaten to report them to the child protective services agency (Dirección de Niñez, Adolescencia y Familia – DINAF), to remove their small children – who aren’t safe at home because they don’t have one, because they lost it when rent came due. These are poor families that the pandemic has made even poorer, and who now have to endure yet another burden – discrimination.

The people on the streets previously worked in construction, transportation, electrical services, domestic jobs, and more. They all have one thing in common: they haven’t been able to self-quarantine, order food deliveries, or go for a car drive just because they’re tired of staying at home. They endure rejection by those who have the personal protective equipment to safely go out, because they fear hunger more than COVID-19.

An elderly couple begs for money in the rotunda of San Pedro Sula’s monument to mothers. María Angélica Portillo and Felipe Benítez say that their only daughter abandoned them many years ago, so now they have to beg in the streets to survive. San Pedro Sula, July 9, 2020. Photo by Deiby Yánes.

An elderly couple begs for money in the rotunda of San Pedro Sula’s monument to mothers. María Angélica Portillo and Felipe Benítez say that their only daughter abandoned them many years ago, so now they have to beg in the streets to survive. San Pedro Sula, July 9, 2020. Photo by Deiby Yánes. A mother and her baby, Azael, beg for money on Tegucigalpa’s John Paul II Boulevard. Azael was born on March 16, 2020, in a world quarantined by COVID-19. His family has been begging for almost four months to survive, risking curfew violations and possible infection. Tegucigalpa, July 7, 2020. Photo by Martín Cálix.

A mother and her baby, Azael, beg for money on Tegucigalpa’s John Paul II Boulevard. Azael was born on March 16, 2020, in a world quarantined by COVID-19. His family has been begging for almost four months to survive, risking curfew violations and possible infection. Tegucigalpa, July 7, 2020. Photo by Martín Cálix. Henry Hernandez, 35, has been begging on the streets for almost four months so that he can feed his family. Due to the pandemic, the sawmill where he worked for five years fired all its workers and suspended operations. With no job and a family to feed, Henry has resorted to begging for money on Tegucigalpa’s Central America Boulevard, where he has been threatened and insulted. DINAF once warned that he might be separated from his daughter and two sons, which is why they don’t go out to beg with him anymore. His wife, a diabetic who needs her medications, also stays at the home they rent for 2,000 lempiras a month in the September 19th neighborhood. Tegucigalpa, July 7, 2020. Photo by Martín Cálix.

Henry Hernandez, 35, has been begging on the streets for almost four months so that he can feed his family. Due to the pandemic, the sawmill where he worked for five years fired all its workers and suspended operations. With no job and a family to feed, Henry has resorted to begging for money on Tegucigalpa’s Central America Boulevard, where he has been threatened and insulted. DINAF once warned that he might be separated from his daughter and two sons, which is why they don’t go out to beg with him anymore. His wife, a diabetic who needs her medications, also stays at the home they rent for 2,000 lempiras a month in the September 19th neighborhood. Tegucigalpa, July 7, 2020. Photo by Martín Cálix. For three months, Selvin Quinilla, 34, has been begging near the tollbooth on the highway exit south to Tegucigalpa. Selvin says that he was fired from his job at a maquila shortly after the pandemic hit. He has a young daughter and lives in the Chamelecón area. Charity is the only source of income he has left, he says. That street is full of mothers and children asking for help just like Selvin, appealing to the sympathy of drivers. They say that there is no work to be had, so they have to beg for food. San Pedro Sula, July 9, 2020. Photo by Deiby Yánes.

For three months, Selvin Quinilla, 34, has been begging near the tollbooth on the highway exit south to Tegucigalpa. Selvin says that he was fired from his job at a maquila shortly after the pandemic hit. He has a young daughter and lives in the Chamelecón area. Charity is the only source of income he has left, he says. That street is full of mothers and children asking for help just like Selvin, appealing to the sympathy of drivers. They say that there is no work to be had, so they have to beg for food. San Pedro Sula, July 9, 2020. Photo by Deiby Yánes. Melissa (19) and Maria (20) carry their children in their arms and beg in the streets to survive. They were abandoned by their partners when they found out they were pregnant. The young women met in elementary school and have been friends ever since. They now live together with their children in Altos de La Quesada, a gang-controlled neighborhood. Sometimes drivers offer them money for sex, or insult and threaten to report them to DINAF, they say, for begging with their children at the end of Tegucigalpa’s beltway. They have no other options, and haven’t had any for four months. Tegucigalpa, July 7, 2020. Photo by Martín Cálix.

Melissa (19) and Maria (20) carry their children in their arms and beg in the streets to survive. They were abandoned by their partners when they found out they were pregnant. The young women met in elementary school and have been friends ever since. They now live together with their children in Altos de La Quesada, a gang-controlled neighborhood. Sometimes drivers offer them money for sex, or insult and threaten to report them to DINAF, they say, for begging with their children at the end of Tegucigalpa’s beltway. They have no other options, and haven’t had any for four months. Tegucigalpa, July 7, 2020. Photo by Martín Cálix. Maria, 20, carries her son while she begs for money or food. For the last four months, Maria has had to endure insults and sexual harassment from the drivers she approaches for help. Maria, who lives in a gang-controlled neighborhood, was abandoned by the father of her child when she got pregnant. Tegucigalpa, July 7, 2020. Photo by Martín Cálix.

Maria, 20, carries her son while she begs for money or food. For the last four months, Maria has had to endure insults and sexual harassment from the drivers she approaches for help. Maria, who lives in a gang-controlled neighborhood, was abandoned by the father of her child when she got pregnant. Tegucigalpa, July 7, 2020. Photo by Martín Cálix. Don Orlando, a diabetic, asks for help at a traffic light in Dos Caminos, Villanueva, Cortés. He says being in a wheelchair is dangerous when he’s on this highway, which runs toward San Pedro Sula. Things have gotten worse in the past few months of the COVID-19 crisis. He says that drivers don’t give as much money now, and there are more children begging, which affects how much he can collect. Dos Caminos, Villanueva, Cortés. Thursday, July 9, 2020. Photo by Deiby Yánes.

Don Orlando, a diabetic, asks for help at a traffic light in Dos Caminos, Villanueva, Cortés. He says being in a wheelchair is dangerous when he’s on this highway, which runs toward San Pedro Sula. Things have gotten worse in the past few months of the COVID-19 crisis. He says that drivers don’t give as much money now, and there are more children begging, which affects how much he can collect. Dos Caminos, Villanueva, Cortés. Thursday, July 9, 2020. Photo by Deiby Yánes. Stranded in Honduras after the Segovia Circus from Mexico closed down, Maritza and her family have been forced to beg for money to survive. This family of circus workers was abandoned in Honduras with no way to return home to Mexico. Tegucigalpa, July 8, 2020. Photo by Martín Cálix.

Stranded in Honduras after the Segovia Circus from Mexico closed down, Maritza and her family have been forced to beg for money to survive. This family of circus workers was abandoned in Honduras with no way to return home to Mexico. Tegucigalpa, July 8, 2020. Photo by Martín Cálix. Ivan, a dump truck driver, lost his job just before the pandemic. Soon after, a nationwide lockdown was declared, but he and his family — wife and three daughters — have not been able to comply with the stay-at-home order. With no savings, job, or other prospects, he has been forced to ask for help on Central America Boulevard. Tegucigalpa, July 7, 2020. Photo by Martín Cálix.

Ivan, a dump truck driver, lost his job just before the pandemic. Soon after, a nationwide lockdown was declared, but he and his family — wife and three daughters — have not been able to comply with the stay-at-home order. With no savings, job, or other prospects, he has been forced to ask for help on Central America Boulevard. Tegucigalpa, July 7, 2020. Photo by Martín Cálix. Dozens of people, mostly from the Lempira neighborhood of Chamelecón, go out early in the morning to beg on the highway to Tegucigalpa so they can buy a little food. Mothers with children in arms and entire families cluster around this part of the highway. This is now the daily scene during the COVID-19 pandemic. San Pedro Sula, July 9, 2020. Photo by Deiby Yánes.

Dozens of people, mostly from the Lempira neighborhood of Chamelecón, go out early in the morning to beg on the highway to Tegucigalpa so they can buy a little food. Mothers with children in arms and entire families cluster around this part of the highway. This is now the daily scene during the COVID-19 pandemic. San Pedro Sula, July 9, 2020. Photo by Deiby Yánes. Jenny, 18, after four months of curfew and quarantine, finally had to go out and beg on Tegucigalpa’s beltway. This photo was taken on her first day. Tegucigalpa, July 8, 2020. Photo by Martín Cálix.

Jenny, 18, after four months of curfew and quarantine, finally had to go out and beg on Tegucigalpa’s beltway. This photo was taken on her first day. Tegucigalpa, July 8, 2020. Photo by Martín Cálix. Meilin approaches cars that stop at the traffic light on Paraguay Avenue and John Paul II Boulevard. She approaches holding a cardboard sign that asks for money. She and all her family have to beg because of the unemployment that intensified during the coronavirus outbreak. Tegucigalpa, July 7, 2020. Photo by Martín Cálix.

Meilin approaches cars that stop at the traffic light on Paraguay Avenue and John Paul II Boulevard. She approaches holding a cardboard sign that asks for money. She and all her family have to beg because of the unemployment that intensified during the coronavirus outbreak. Tegucigalpa, July 7, 2020. Photo by Martín Cálix. Taking some time out to rest a little and eat, wheelchair-bound José Luis Villanueva is helped everyday by his inseparable friend, Will Mejía, who pushes him back and forth between cars to beg on the San Pedro Sula beltway. They share equally whatever they’ve collected at the end of the day, they say. Don José Luis told us that he pays a daily rent of 130 lempiras for a room in the Medina neighborhood, and also must earn enough to help buy groceries. His wife sometimes sells food that she cooks, but it’s not enough for them and their closest granddaughter, who can’t find work either. He says that before the pandemic, he used to collect more money on the streets. But now, he doesn’t even get half of what he used to because people are afraid of getting infected and don’t even roll their car windows down. San Pedro Sula, July 9, 2020. Photo by Deiby Yánes.

Taking some time out to rest a little and eat, wheelchair-bound José Luis Villanueva is helped everyday by his inseparable friend, Will Mejía, who pushes him back and forth between cars to beg on the San Pedro Sula beltway. They share equally whatever they’ve collected at the end of the day, they say. Don José Luis told us that he pays a daily rent of 130 lempiras for a room in the Medina neighborhood, and also must earn enough to help buy groceries. His wife sometimes sells food that she cooks, but it’s not enough for them and their closest granddaughter, who can’t find work either. He says that before the pandemic, he used to collect more money on the streets. But now, he doesn’t even get half of what he used to because people are afraid of getting infected and don’t even roll their car windows down. San Pedro Sula, July 9, 2020. Photo by Deiby Yánes.