Translation by: John Turnure

Led by General Tito Livio Moreno, the Armed Forces are the most prominent institution in critical areas of the fight against the pandemic. On July 24, Brigadier General José Ernesto Leva Bulnes was appointed president of the supervisory board of Inversiones Estratégicas de Honduras (Invest-h), an institution that administers 3.7 billion lempiras earmarked for pandemic-related efforts, and which is being investigated for corruption by the Public Prosecutor’s Office.

Just like the budgets for health, education, energy, and security, the Ministry of Defense’s budget was exempt from the 2% budget reduction mandated by executive decree PCM 020-2020 for all the non-financial public sector institutions in order to free up money for the pandemic effort.

The additional tasks taken on by the Armed Forces during the pandemic have been the justification for the questionable expenditures. In an interview with Contracorriente, AF spokesperson José Coello said “… we have not made any direct purchases. We do not buy medical equipment and we are not in charge of purchases in a public health emergency”. However, documents published on the government’s transparency portal (Instituto de Acceso a la Información Pública – IAIP) indicate that in direct procurements alone, the Ministry of Defense disbursed (through the Armed Forces) L4.129 billion in 51 small procurement contracts between March and June of this year. This expenditure is equivalent to 80% of the budget that the national teaching hospital (Hospital Escuela Universitario), one of the country’s main public health care centers, has spent during the pandemic.

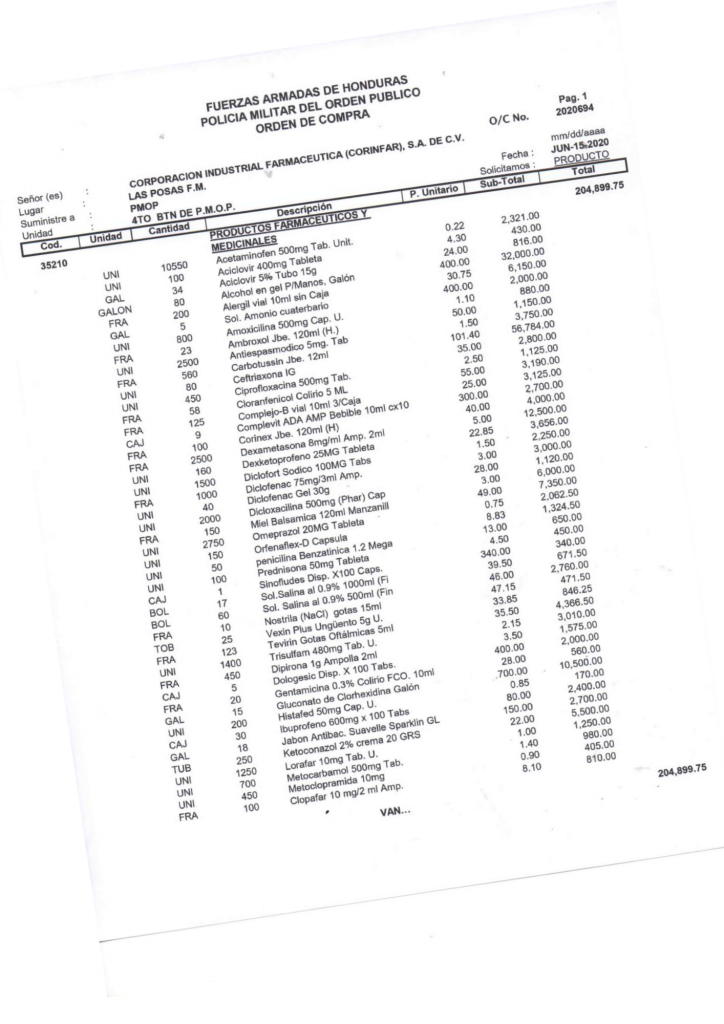

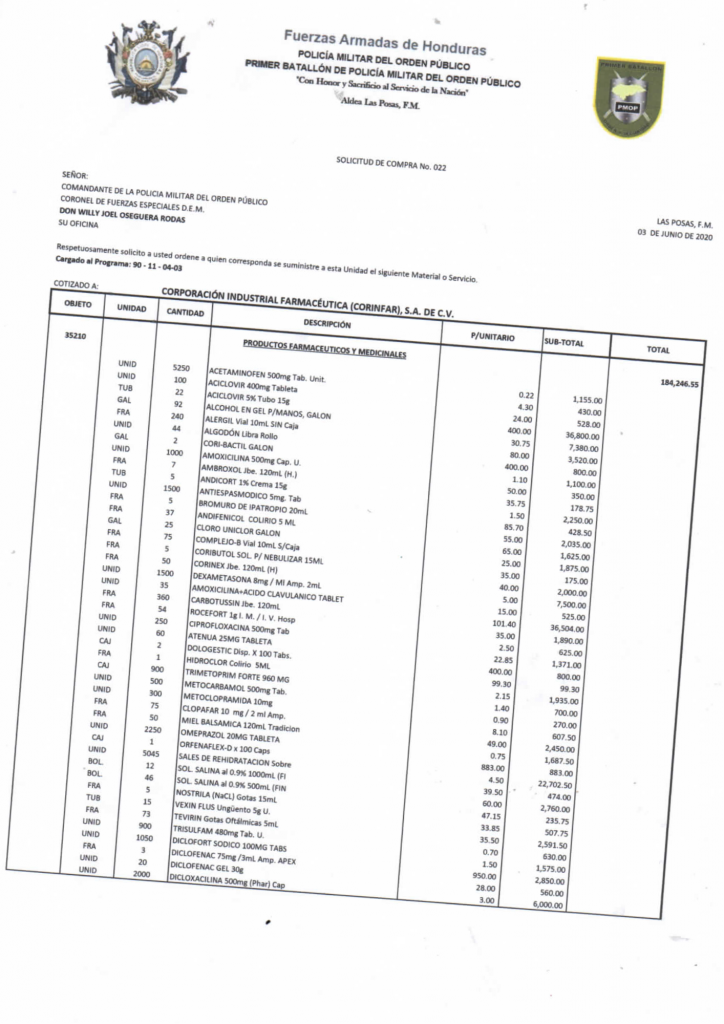

The budget allocated to the Ministry of Defense has been spent on its operational needs, such as the purchase of drugs to treat the virus in the medical clinics and offices of various military units. Yet irregularities in the Ministry of Defense’s expenditures have been found. Purchase order number 2020008, issued on April 18 by the military police’s general command (Comando General de la Policía Militar del Orden Público – PMOP) is for “medicines and medical supplies for the use, treatment and prevention of COVID-19, for military police personnel in the medical clinics located in Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula military installations”. The L268,000 purchase order was issued to Corporación Industrial Farmacéutica S.A. de C.V. (Corinfar), which in the past has been cited by the Public Prosecutor’s Office for inflating the prices of medicines and supplies.

In 2017, a special prosecutor from the Public Prosecutor’s Office noted that six companies were given 1,352 purchase orders for drugs with inflated prices between 2008 and 2015. Corinfar was the largest beneficiary of these inflated purchase orders that amounted to L182.4 billion. The Public Prosecutor subsequently initiated an investigation and documents were seized from the Ministry of Health. However, no summonses have been issued yet and the case has not reached the courts. In 2013, the company was also linked to a case in which five Ministry of Health employees and a Corinfar executive were accused of at least 22 crimes and stealing almost two million units of medicine from the central government’s medicine stock (Almacén Central de Medicamentos) to later sell them.

The Military Police has so far disbursed L806,000 in three purchase orders to Corinfar for medicines, mostly to treat allergies, flu and cough.

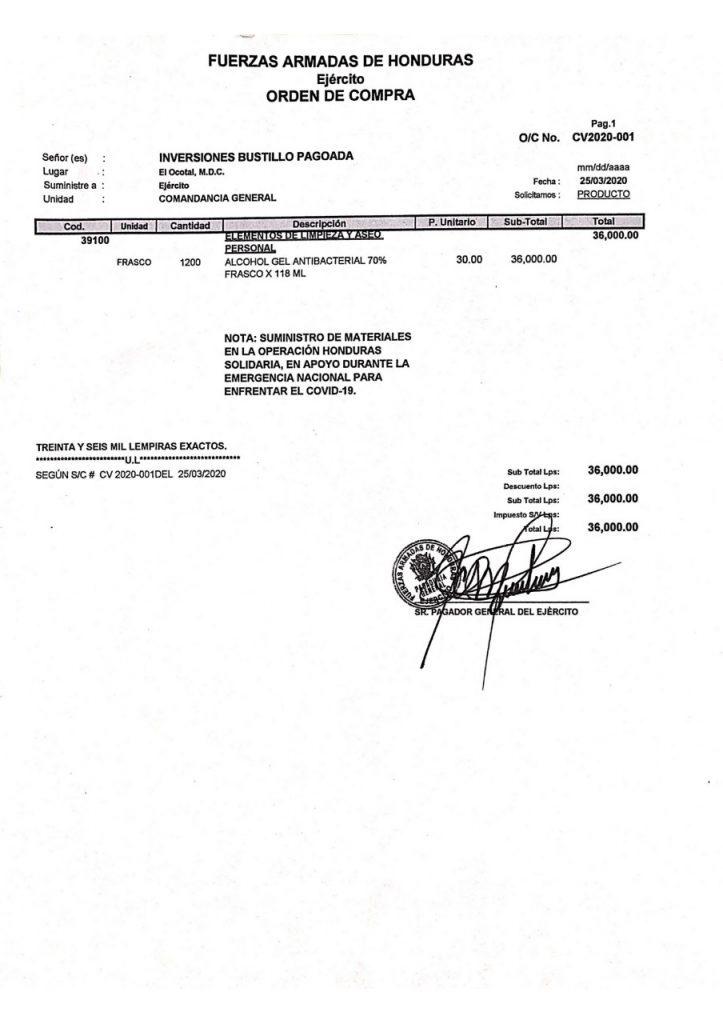

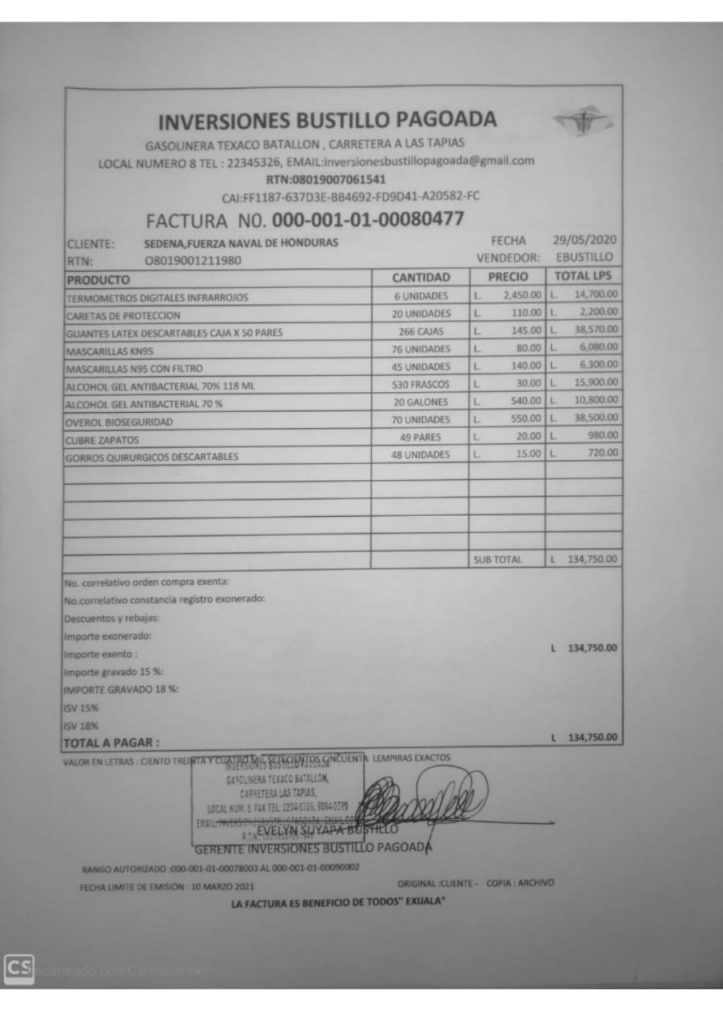

Furthermore, the Military Police, Navy, Army and Air Force have decided to allocate portions of their budgets to the purchase of medicines and biosecurity supplies. Contracorriente found that some of these purchases were made from a company owned by the close relatives of a Honduran Air Force officer.

Air Force procurement reports indicate that Evelyn Suyapa Bustillo Pagoada, wife of Air Force Major Marvin Leonardo Meléndez, is the manager of the Inversiones Bustillo Pagoada S. de R.L., a company that buys and sells medicines through the Eviba Pharmacy. This pharmacy is located in a gas station near the First Infantry Battalion base in Tegucigalpa. The Army, Navy and Air Force executed seven procurement processes (through June 2) totaling L235,650 for purchases from this company. These purchases included one made by the Army (for Ivermectin, a component of the MAIZ treatment promoted by the government) for almost twice the price (L33 per unit) paid six days later by the Armed Forces’ military industries (Industria Militar de las Fuerzas Armadas – IMFFAA) to buy the same medicine from Corinfar (L18 per unit). In addition, the documents indicate that Inversiones Bustillo Pagoada is not currently certified to bid on government contracts and procurements (Oficina Normativa de Contratación y Adquisiciones del Estado – ONCAE).

These purchases of drugs and biosafety equipment are justified in the reports as inputs for the treatment of Armed Forces personnel who have been exposed to the virus due to their assignment to pandemic-related tasks. The purchase orders were signed and authorized by Colonel Willy Oseguera, the PMOP commander, without any evidence of approval by a health care professional.

On May 20, General Moreno reported that approximately 250 active Armed Forces personnel had contracted the virus.

An Army soldier on duty at a police checkpoint on Morazán Boulevard in the Honduran capital. Tegucigalpa, April 15, 2020.

An Army soldier on duty at a police checkpoint on Morazán Boulevard in the Honduran capital. Tegucigalpa, April 15, 2020.How are the Armed Forces handling the pandemic?

An anonymous source working in a unit within the National Inter-Institutional Security Force (Fuerza de Seguridad Interinstitucional Nacional – FUSINA), which includes members of the National Police and branches of the Armed Forces such as the Military Police, Navy, Air Force, Army and Anti-Gang Unit, told Contracorriente that 35% of their colleagues are infected with COVID-19, and that there is an underlying fear and dissatisfaction within the institution due its failure to contain the pandemic.

“There were some rapid tests done in the unit, resulting in 32 people testing positive. They were then quarantined at the base until the final swab test results came back 14 days later. The final results showed that only 17 were positive, but since everyone was quarantined in the same place, they all got infected”. He also said that his unit is not happy with the way it has been treated since the pandemic started. Their monthly base pay is 7,000 lempiras, but early in the pandemic they were ordered to remain on duty for 90 days in a row without time off, and were not allowed to visit their families.

“The workload doubled – they were really taken advantage of. It’s always unfair… an officer is not going to work like that for base pay. The soldiers always get the worst of it” he explained, adding that the treatment at the Military Hospital includes the MAIZ treatment (microdacyn, azithromycin, ivermectin and zinc), but that they don’t like to take the medicine because it makes their hearts race.

In April, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a statement warning about the counterproductive effects of using these drugs to treat COVID-19. The FDA warned of serious heart rhythm problems in patients treated with azithromycin combined with hydroxychloroquine, another Honduran government treatment for hospitalized patients.

Regarding the medicine purchases by units that aren’t part of the Military Hospital, Dr. Ligia Ramos of the Honduran Institute of Social Security (IHSS) and a Honduran Medical Association board member, believes that these purchases are evidence that the Armed Forces have more coronavirus cases than they are reporting. “The Military Hospital is supposed to treat these cases, but it doesn’t seem to have the capacity to handle them all, so other units are self-medicating. But we must point out that the Ministry of Public Health should be responsible for directing the pandemic effort and medical treatment. The truth is that is public officials and the Armed Forces don’t have the technical expertise to do this”.

The pandemic has clearly revealed what happens when a country invests more in security and defense than public health. The budget for security and defense in 2020 is L8.477 billion, approximately L200 million more than in 2019. Data from the Stockholm International Peace Studies Institute (SIPRI) indicate that as of 2019, Honduras was the Central American country with the highest percentage of GDP invested in its military capability.

In a phone interview, Dr. Ramos reiterated that “it’s very disheartening that all that military spending could have been invested in improving the health system long before the pandemic, but it was being spent on the Armed Forces and also stolen”.

An analysis of the Ministry of Finance and Armed Forces reports on pandemic-related spending show that compared to the Hospital Escuela’s L5.1 million budget, the Navy alone has spent half this amount in fuel to staff the lockdown checkpoints and patrols. In addition, the Armed Forces reports that the L2.5 million were paid to Inversiones Amor S. de R.L., a company that prior to the COVID-19 pandemic did not have an ONCAE registration to participate in government procurements.

Military training exercise prior to scheduled home medical visits by the Ministry of Health and Copeco. The Army accompanies the medical brigade doctors for protection in neighborhoods controlled by gangs. Tegucigalpa, July 9, 2020. Photo: Martín Cálix.

Military training exercise prior to scheduled home medical visits by the Ministry of Health and Copeco. The Army accompanies the medical brigade doctors for protection in neighborhoods controlled by gangs. Tegucigalpa, July 9, 2020. Photo: Martín Cálix.Pandemic management

Invest-h bought seven mobile hospitals for L1.2 billion from Elmed Medical, a company owned by Axel Lopez, who was reported by SDI Global LLC for alleged fraud. According to their allegations, Lopez obtained a quote from SDI Global for the mobile hospitals, and then plagiarized SDI’s proposal by copying its specifications and international operations registration code to his own proposal submitted to Invest-h. Consequently, Marco Bográn, a former Invest-h director, is being investigated by the Public Prosecutor’s Office for allegedly committing the crimes of fraud, misappropriation of public funds, abuse of authority, and violation of the duties of public officials.

Two of these seven mobile hospitals arrived on July 10 and are currently being inspected by the Public Prosecutor’s Office to verify their condition. Once this is complete, the mobile hospitals will be transported to sites in Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula, to be administered by the Armed Forces.

Despite the accusations of corruption pertaining to the mobile hospitals, AF spokesperson José Coello declared that “efforts are moving forward” and that two officers have already been appointed to administer the mobile hospitals, which will alleviate some of the burden on other hospitals. The Tegucigalpa mobile hospital will be administered by Army Infantry Colonel Leonel Mazzoni Hernández, whose previous assignment was deputy financial manager of the Military Pension Institute (Instituto de Previsión Militar).

This is not the first time that the military has taken over the administration of health care systems. Retired General Edilberto Ortiz Canales has been a member of the supervisory board of the Hospital Escuela Universitario in Tegucigalpa since 2018.

Ortiz Canales told Contracorriente that the Armed Forces have provided biosecurity supplies to employees and patients at the Hospital Escuela, and that the hospital staff can count on the Armed Forces for any need. “I am responsible for the logistical processes and systems, to ensure that all the resources at hand reach the end user expeditiously. By this, I mean the procurement of supplies, including medicines and medical equipment. Since our arrival, the hospital has been improving its entire logistics and procurement system”, says Ortiz, who previously served as the director of the Military Hospital.

As to questions about the resources allocated to the public health system compared with the investment in security, Ortiz believes that the government has fully met expectations and has provided an optimum level of care to the public. “The Hospital Escuela has been adequately resourced, and has received what it needs to improve the health care of the Honduran people. We provide almost 80% of the country’s supply of medicine – we are meeting the need. That’s why I believe the government’s support of the hospital has been excellent in these circumstances”.

Two soldiers enter the Hospital Escuela Universitario. Tegucigalpa, June 10, 2020. Photo: Martín Cálix.

Two soldiers enter the Hospital Escuela Universitario. Tegucigalpa, June 10, 2020. Photo: Martín Cálix.Regarding the Armed Forces’ role in public affairs and in this crisis, Leticia Salomón, a Honduran sociologist and economist with the Honduras Documentation Center (Centro de Documentación de Honduras – CEDOH), believes that “it’s a combination of the AF’s growing distrust of civil institutions and its own leadership, together with its admiration of military discipline and obedience to the command structure. The military ranks are solidly present, grateful for what they have, and unconditionally loyal”. Salomón also notes that the support functions entrusted by the government to the Armed Forces aren’t free and neither are they new, as they originated in past administrations.

“The Armed Forces have played a leading role in domestic security since Ricardo Maduro’s administration. He initiated the Honduras Segura program in which the soldiers boarded buses in pairs to “deter” criminals. His administration had to suspend this after 3-4 weeks due to the millions that the Armed Forces was charging for this service. A retired general told me that they charged for the service because they were incurring an expense for a function that pertained to a civilian institution. I assume that this practice became the norm, which begs the question – how much income does the Armed Forces receive now for all the “new missions” they are being assigned by the government? I’m referring to functions assigned to the Armed Forces as an institution, and not retired military personnel appointed to positions in agricultural development, transportation and installation of hospitals, and delivery of the bolsa solidaria (food assistance packages)” she concludes.

A Military Police vehicle enters the National Cardiopulmonary Institute, better known as the Tegucigalpa Thorax Hospital, July 14, 2020.

A Military Police vehicle enters the National Cardiopulmonary Institute, better known as the Tegucigalpa Thorax Hospital, July 14, 2020.The Military Hospital

President Juan Orlando Hernandez was treated at the Military Hospital after he announced on June 16 that a PCR (polymerase chain reaction) test showed he was positive for coronavirus. This hospital is primarily funded by a 6% salary contribution from all active and retired Armed Forces personnel, civil police, and IPM employees, plus a government appropriation authorized by law (Ley de Presupuesto General de Ingresos y Egresos a la Secretaría de Estado en el Despacho de Defensa Nacional). This is why the president, the commander-in-chief, was treated there despite the criticism it drew. According to Magda Ferrera, the Military Hospital’s communications officer, no other soldiers being treated there for the coronavirus received any less care due to the president’s hospitalization.

Social network posts requesting that the Military Hospital be opened to the general public began to appear. One such post was from a public health expert, Dr. Marco Eliud Girón, who said in a media interview “that no one should be afraid to demand this of the military hospital – it’s the only hospital that’s empty”. This demand was echoed by the former head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Romeo Vásquez Velásquez, leader of the 2009 coup d’état.

“There is a twofold benefit to the Armed Forces by opening its hospital to the public. They’ll receive the gratitude of the people, and they can expand their infrastructure, equipment and even medicine stock”, Velasquez said. But he also confirmed what Solomon previously said – the military’s services aren’t free.

To this, General Moreno, head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, stated that “the Military Hospital belongs to all those affiliated with the IPM, about 50,000 people plus their families. We all contribute 6% from our salaries for the purchase of medical supplies, physical facilities and other logistical and operational needs. It’s important to note that all this relieves the IHSS and other health care institutions of a great burden. We have also responded to public emergencies and made our entire infrastructure available to the public. What we don’t like is people who criticize the institution for their own benefit, to divert our water to their own crops”.

Human rights violations during the pandemic

On April 25, a wall of fire and stones blocked the street at the entrance to the small coastal village of El Paraíso, in the municipality of Omoa, Cortés. The villagers were protesting the murder of Marvin Rolando Alvarado, a 32-year-old baker who lived in the area.

According to the La Prensa newspaper’s reporting of information from the Department of Police Investigations (Dirección Policial de Investigaciones – DPI), Marvin died at the Mario Catarino Rivas hospital after being detained at a military checkpoint for driving after curfew with his two cousins and brother, Arturo. According to information from the Honduran Families of Detained and Disappeared Persons (Comité de Familiares de Detenidos y Desaparecidos en Honduras – COFADEH), the Military Police detained, beat, and ultimately shot them. Marvin did not survive.

In addition, COFADEH reported that when Arturo was discharged, the police took him directly to the DPI offices to intimidate him because he allegedly had attacked the Military Police. According to COFADEH, Marvin’s younger brother, Arturo, decided to take his own life two weeks later because of this intimidation.

Dina Meza, president of the Association for Democracy and Human Rights (Asociación por la Democracia y los Derechos Humanos – ASOPRODEHU), which also followed the case, told Contracorriente that two of the police officers involved were arrested as a result of complaints to the National Human Rights Commissioner (Comisionado Nacional de Derechos Humanos – CONADEH), who requested the Public Prosecutor’s Office to investigate the death of Marvin Alvarado.

In this context, CONADEH published a report indicating that since the state of emergency was declared, they have received 3,179 complaints, of which 1,198 were directly related to the government measures to combat COVID-19. Fifty-seven percent of these complaints were against central government officials: 299 complaints against the Ministry of Health, 110 against the National Police, 127 against municipal officials, and 50 against prison officials.

The report states that most of the complaints resulted from the provision of health services and personal protection equipment, curfew-related restrictions, food distribution programs, deprivation or lack of access to public services, economic measures or effects, and work-related issues.

Military personnel man a police checkpoint at the highway exit from the Honduran capital to El Paraíso. Tegucigalpa, July 3, 2020. Photo: Martín Cálix.

Military personnel man a police checkpoint at the highway exit from the Honduran capital to El Paraíso. Tegucigalpa, July 3, 2020. Photo: Martín Cálix.COFADEH’s coordinator, Berta Oliva, says that “there’s nothing more to wait for… Honduras has hit rock bottom regarding human rights issues. The military presence isn’t here to combat the virus or the pandemic, but to instill fear and paralyze the public. People are afraid of dying from starvation, dying from the virus, and dying from the repression. The pandemic suits this dictatorship perfectly because it has invigorated the Armed Forces and held them up as the country’s saviors from the problem”.

The protests in El Paraíso ended on April 27 after dozens of people attended Marvin Alvarado’s funeral. Carrying banners, wearing face masks, and demanding justice, the community marched in front of the car carrying the young man’s coffin. In statements to a local media outlet, Jaime Alvarado, another of the victim’s brothers, said the military told him “you’re next”.

Military participation in government welfare tasks

The relatives of COVID-19 victims have been displaced at the funerals by military and police personnel who, according to the Armed Forces spokesperson, are only there to “maintain control” and ensure that no more than 10 people attend each funeral.

However, in early May we heard about the family of Don Luis, a patient with bilateral pneumonia and possibly COVID-19, who died in an IHSS ward in San Pedro Sula. His family reported the military’s poor treatment of Don Luis’ body, saying that FUSINA agents threatened to take the body to a mass grave in an unspecified location of Cortés department, without any proof that his death was due to COVID-19. The only option for his family was to cremate the body.

Regarding this specific case, Edwin Lanza, president of the Honduran Association of Funeral Homes, confirmed that “this type of Army interference is not allowed. The only thing FUSINA should do is escort the coffin as it’s being transported. They shouldn’t interfere regarding what should or shouldn’t be done. The relatives are the ones who decide”.

Four young soldiers walk through the vocational training institute’s facilities (Instituto Hondureño de Formación Profesional – INFOP). Tegucigalpa, April 8, 2020. Photo: Martín Cálix.

Four young soldiers walk through the vocational training institute’s facilities (Instituto Hondureño de Formación Profesional – INFOP). Tegucigalpa, April 8, 2020. Photo: Martín Cálix.Contracorriente requested information from the Ministry of Defense about the number of burials escorted by FUSINA and the Military Police. However, the response from the inspector general’s office for the Armed Forces was “we are not authorized to provide this type of information, since our function is only to cooperate with other institutions”.

In addition to escorting burials of COVID-19 victims, the Armed Forces have managed the logistics of distributing face masks made by IMFFAA, as well as the food distributions under the Honduras Solidaria government program.

In response to the increased food insecurity experienced by many families as a result of the containment measures, and which closed many businesses for months, the government began the Honduras Solidaria program, which aimed to distribute food rations to 3.2 million people nationwide.

The Bolsa Solidaria is a small, clear plastic bag that includes a Bible pamphlet and a three-day food supply. It’s delivered by the military every two weeks to families in slums, market vendors, and those working in transportation and other informal businesses.

According to Joaquín Mejía, a PhD in human rights, “The Armed Forces have taken advantage of the chaos to see how they can benefit. But they’ve forgotten all about the Agricultural Development Program that was approved last year with L4 billion in funding to be administered by the Armed Forces. The government forces people to stay home, but 70% of the population works in the informal economy and has to go out to earn their daily bread. What has the Armed Forces done with this money? Well, the answer is always the same – unfortunately, it’s been stolen”.

Mejía pointed to a report by the Committee for Free Expression (Comité para la Libre Expresión – C-libre) that has documented more than 80 demonstrations demanding the right to food during the pandemic. “And who do you think was cracking down on those protests? According to that report it was the military and the police”.

Military personnel unload a Honduran Army truck to deliver food under the “Honduras Solidaria” government program. Tegucigalpa, April 8, 2020. Photo: Martín Cálix.

Military personnel unload a Honduran Army truck to deliver food under the “Honduras Solidaria” government program. Tegucigalpa, April 8, 2020. Photo: Martín Cálix.***

After he was sworn in, General José Leva Bulnes, the new chairman of Invest-h’s audit board, emphatically declared that corruption would not be covered up, and publicly stated “God help Honduras. As a God-fearing man, I can say that our determination and wish is to complete our work in 180 days, and leave behind a completely transparent institution”.

For Leticia Salomón, this is typical of “a pattern established by the current president, who since his time as leader of the National Congress, showed his favoritism for the military and its involvement in domestic security tasks and the repression of social protest. In exchange, the military benefited from regular budget increases for domestic security functions, to the detriment of the health and education budgets. This is a direct cause of the instability in which the public health system now finds itself with the pandemic”.

In addition, Solomon notes that there are two key aspects of President Juan Orlando Hernandez that help explain the heavy Armed Forces involvement in government functions. “He seems to be a frustrated military man. He attended the military academy, and I imagine that he has a certain admiration for and closeness with those who serve in the military. In addition, he uses the military as his private security force to hold power despite domestic and international charges of corruption and drug trafficking”.