Text: Óscar Estrada

Illustration: Kenny Reyes

Translation by Ann Deslandes

“I have an aunt who gets her news from TikTok,” says Paola Palacios, a Honduran whose family lives in Arizona in the United States.

Palacios says that international news in Arizona is usually quite superficial. So, to keep in touch with what people in her country are goig through, her aunt watches TikTok videos, specifically, “videos of ordinary people giving their opinion about what is happening.”

Palacio’s family traveled to the United States decades ago. One aunt went there by plane, another via a people smuggler; and an uncle left when Hurricane Mitch happened and he obtained Temporary Protected Status.

Today, the three of them connect with what’s happening in Central America through TikTok, which launched in China in 2016 and has almost 1 billion users worldwide.

In a phone interview, Palacios gives the example of a video of Salvadoran president, Nayib Bukele, shared by her aunt.

In the video, someone says it was okay for them to put members of MS-13 in jail in El Salvador.

“My aunt … believes that Bukele is cleaning up society and (thinks) that what is happening there is okay, so she shared the video,” said Palacios.

Palacios says that her other uncles and aunts have preferred to disconnect, because, when it comes to looking back to Honduras and the region, hopelessness reigns.

For them, she says, “Everything that happens in Honduras is bad, everything is wrong there, there are no solutions.”

Palacios lived in China for four years, working as a dentist through an exchange program. Since returning to Honduras a year ago, she has sought to connect with her family in the United States, believing it important to keep them connected to what is happening in the country. She currently lives in Tegucigalpa and, although from abroad she had sometimes wanted to go back, the difficult economic situation in Honduras makes her want to emigrate again.

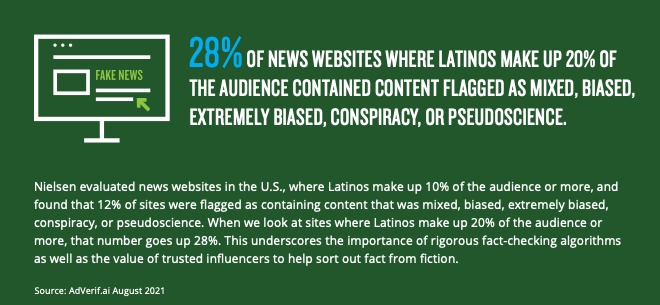

In September 2021, U.S. media monitoring company Nielsen published the report Inclusion, information and intersection, the truth about connecting with U.S. Latinxs, which analyzes some 100 U.S. news sites across the political spectrum, including some Spanish-language sites. The report describes the Latinx population in the U.S. as highly vulnerable to fake news and misinformation on social networks.

For news websites where Latinxs represent 10% or more of the readers, 12% of the content was flagged as a mix of fake and real news, biased, extremely biased, conspiratorial or pseudoscientific. Those numbers increase as the proportion of Latinxs in the audience increases: “Where Latinxs represent 20% or more of the audience, that figure rises to 28%,” the report notes.

It found that the sites with the largest non-Latinx audiences have more rigorous fact-checking algorithms, as well as trusted influencers who help distinguish fact from fiction.

In an interview with NBC News, Stacie Dearmas, vice president of diverse perspectives at Nielsen, said websites with more Latinxs in their audience contain “more conspiratorial or pseudoscientific” material.

“If you are white (in the United States) your chances of seeing that type of content are less than if you are Hispanic,” Dearmas warned.

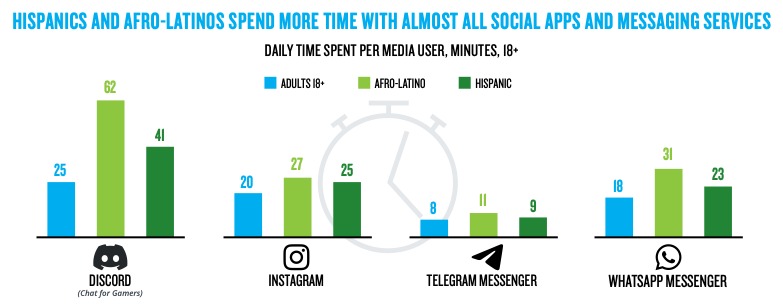

“Misinformation poses a threat to Hispanics, who are particularly vulnerable due to a greater reliance on social media and messaging platforms,” states the Nielsen report, which highlighted Latinxs as “avid users of these apps.”

The 2020 U.S. Census estimated that there are currently 65.3 million Latinxs living in the country, representing 20% of the total population. According to the census, the population is increasing by 1.1 million people each year, largely due to migration.

The majority of Hispanics in the U.S. are of Mexican descent, followed by Puerto Ricans and Cubans. There are currently 2.3 million Salvadorans, 2 million Dominicans, 1.5 million Guatemalans and nearly 800,000 Hondurans in the country. These nearly 8 million Central American migrants represent a vital flow of foreign currency to their countries of origin.

Indeed, according to Central American central banks, the year 2021 closed with record remittance figures. In global numbers, the region exceeded US$32 billion in remittances, which represented up to 26% of the Gross Domestic Product. Guatemala received US$15.183 billion this year, El Salvador received US$7.4 billion and Honduras received US$7.38 billion.

A University of Baltimore study published in 2019, called The Economic Cost of Bad Actors on the Internet, analyzes the impact of misinformation on the U.S. economy. The study found that “financial misinformation is hurting consumers by more than US$17 billion per year,” and that three in five USians “say the spread of fake news has made it harder to make critical financial decisions.”

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002 for his book, Prospect Theory. He says the information we receive helps us make economic decisions.In the context of the diaspora in the United States, the decisions people make regarding their countries of origin — whether or not to send money, which project or which politicians to support, whether or not to return to the country — are influenced by the information they access on social networks.

Luis Assardo, a journalist, professor, and consultant on digital issues, says that to understand the problem of disinformation in the diaspora we must first understand taht technology that “has facilitated access to information and allows any type of data to circulate and reach anyone, has not been circulating at the same speed as media literacy.”

Media literacy “allows people to understand how the Internet works and why they end up accessing certain information.”

According to Assardo, “digital bubbles” are formed, for example, “when there is a WhatsApp group and within the group there is someone who questions something that has been shared and that does not go in line with what the rest of the group has been sharing.”

This dissent “will generate a series of counter discussions, and that person will end up avoiding participating or leaving the group. When this happens, the only people left in the group are those who share the same opinion and no one will question the dominant opinion,” he said.

For Assardo, these “digital bubbles” favor the distribution of fake news in the general population.

Honduran psychologist Warren Ochoa explains that the guilt migrants feel about their absence from important moments in their family makes those digital bubbles more important than verified information.

“If people don’t experience guilt, we don’t transgress social norms. People who migrate experience this feeling of guilt in a very intense way. Say I am sending resources, remittances from the United States or wherever I am, but at the same time I am not living with these people who are supposed to be the reason why I migrated. What happens, for example, when I am far away while my parents get old or sick, I miss someone’s birthday and no matter how many gifts or video calls it is not enough, I am not there, I do not share [my home country] with my children? That makes me feel guilty,” he explains.

Ochoa adds that, when migrants arrive in the United States they come up against a glass ceiling: the limitation of language, culture and nostalgia for belonging. To resolve the guilt and this disconnection with their places of origin, Ochoa explains, migrants in the diaspora share information from their countries that, as we have already seen, are amplified through digital bubbles.

According to the 2020 census, of the 60 million registered Hispanics in the country, 71% (40 million) reported speaking Spanish regularly at home. It is by far the second most-spoken language in the country. But the options for receiving information for the English-speaking population are not the same as those for the Hispanic population. Of the 12 most important open channels in the United States — A&E, ABC, CBS, Fox, ION TV, My Network TV, NBC, PBS, The CW, WGN — only two channels, Telemundo and Univision, offer programming in Spanish. The proportion is much more dramatic in radio and print media.

So where does the Central American diaspora receive information in Spanish?

Reflecting on her family, Palacios notes that, within the newscasts in Arizona, “Telemundo or Univision provide national news and then international news, but very superficially. So, to know a little more about what is happening in her country or what people are thinking, my aunt watches TikTok videos.”

Gilma Agüero is a retired doctor who lives in San Pedro Sula. She has four siblings who emigrated to the United States.

Agüero gives the example of her brother, who she says believes that violence in Honduras continued to rise during the government of Juan Orlando Hernández (2014-2022), despite the fact that he was not in the country and statistics showed the opposite. Agüero says her brother was left with the idea of a country that got a bad reputation in 2012, when it was considered the most violent country in the world.

“Yes, there was (violence),” she says, “but we have not returned to the situation we were in before.”

Another brother of Agüero’s came to the US three years ago. “He told him no, that the situation was no longer the same, but he doesn’t believe it.”

Of the 65 million Latinxs reported by the 2020 census in the United States, almost 30 million are over the age of 35. Of those, an average of 15 million are over 50.

Ochoa says it is important to understand the value that this segment of the population places on the written word, starting with the Bible itself.

For our grandparents and the generations before them, says Ochoa, “when something was written, whether it was in books or newspapers, it was true. If it is written, it is real. Later that mutated to, not only what is written but what was said in the news — if the journalist said it, it was true.”

“That generation that grew up and went through the newspaper, television, radio [era] and arrived late to the Internet, are quite unsuspecting with technology. And on top of that, many of them are products of the 80s and 90s, when critical thinking was practically eradicated,” he said.

‘Authoritative voices’ on social media

Luis Assardo says that the problem of fake news does not lie in an understanding of “the truth,” as Ochoa claims, but with the source.

“It is related to the credibility of the voice speaking,” Assardo says.

“If you trust what I tell you, it doesn’t matter if I am telling you lies … You will not evaluate what I tell you based on whether it is real or not, but simply whether this person is trustworthy or not. That’s called ‘authoritative voice.’”

Assardo adds that it is very difficult for people to believe someone who has never spoken to them before.

“Something happens here that is part of human behavior,” Assardo continues, “If I have publicly said something, if I said it with my voice and my name is on it, I will defend it no matter what, because my name is involved. It may be that I have realized that I am in error, but I will never accept that because I would lose credibility.”

According to the Nielsen report, much of the content on social media platforms is “both user-generated and shared, is in Spanish, Spanglish, or colloquial Spanish.” This “[challenges] conventional fact-checking and content moderation procedures to keep up.”

The information received by migrants in the United States is not only produced inside the country. That is, there are media sources other than those created for the English-speaking population moving through social media networks and created specifically for the Hispanic population.

Assardo says this has been happening in El Salvador “for years” since “the media … discovered that they could expand their audience” via migrants in the US.

“In 2012, the media had reached an audience of 4 or 5 million readers, because that is the number of Salvadorans, but when they saw that the diaspora could also consume the content, they almost tripled their readership,” he said.

Now, says Assardo, because of the diaspora, there are media outlets in El Salvador that have readerships of 13 or 14 million per month, when there are only five or six million Salvadorans in El Salvador.

“The politicians in Central America are looking to hook the diaspora in order to finance themselves, because in our countries remittances are a huge money flow.”

Luis Assardo explains how content – true and false – made for the Northern Triangle diaspora favors Central American state policies. Media agencies have recognized the value of controlling the narratives that travel from the countries to the diaspora and vice versa.

Paola Palacios believes that interacting with her family about what is happening in Honduras has helped them learn more about it.

She visited the U.S. and “began to tell them what had happened with Juan Orlando, how drug trafficking was in the country, how we were politically.”

“These are things they had not heard because they had not had direct contact with someone who was living in the country. I …. informed them, and they said that they had no idea. Then they had more questions, they asked me where they could see more news,” she said.

This article was produces as part of Escuela Cocuyo and El Faro’s Communication Bridges program. Project supported by DW Akademie and the German Federal Foreign Office.