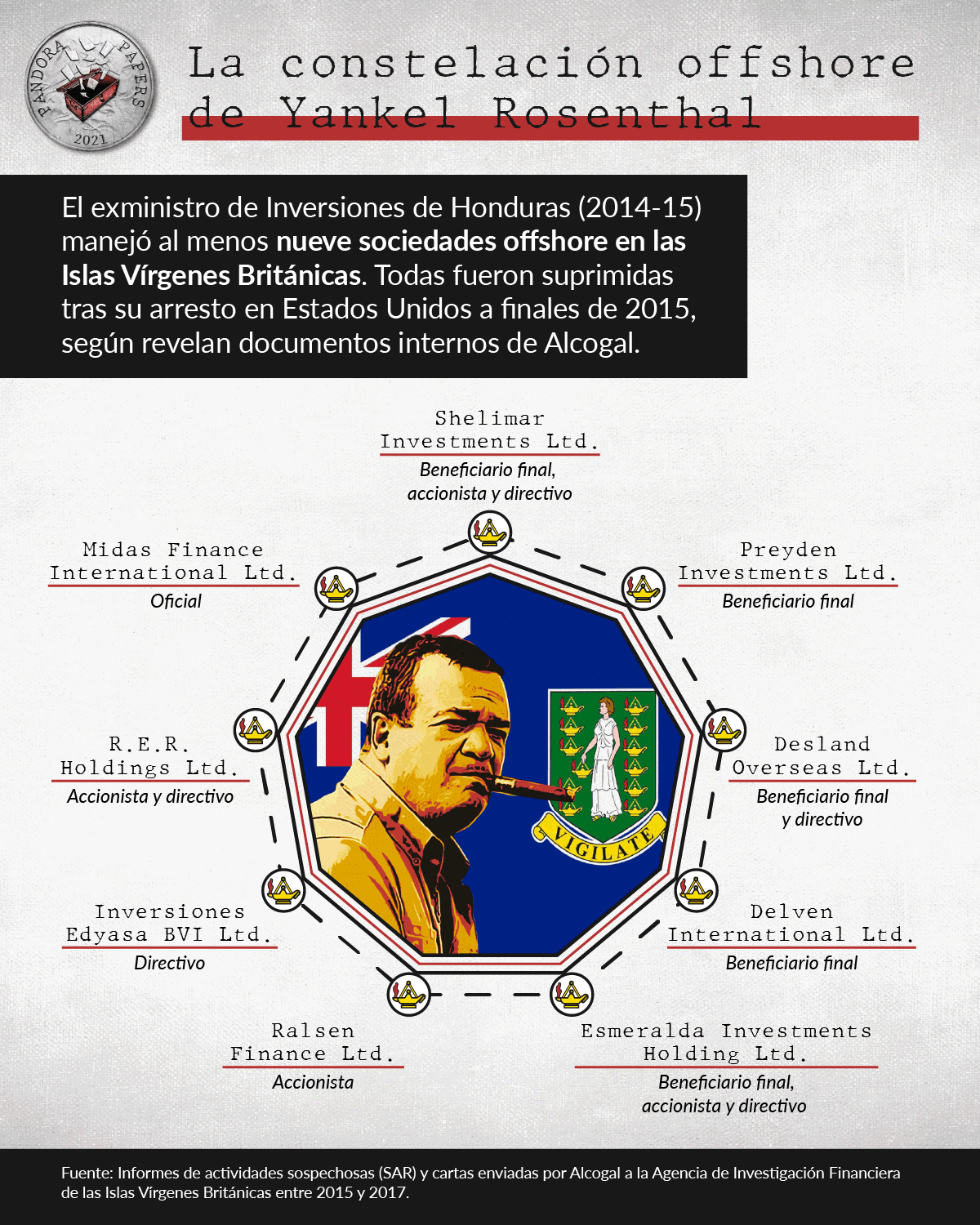

During the trial that ended in a two-year prison sentence in the United States for attempting to do business with drug traffickers, it was revealed that former Honduran minister Yankel Rosenthal Coello had three offshore companies. This journalistic investigation found that he actually had six other companies in tax havens.

By: Jennifer Avila, Andrés Bermúdez Liévano & María Teresa Ronderos*

Illustrations: Miguel Méndez

Photos: Antonio Gutiérrez/ Contracorriente

When Yankel Rosenthal Coello was arrested in a Miami airport in October of 2015, the U.S. prosecutors who were investigating him declassified the secret indictment that they had been putting together. That dossier brought to light three companies in the British Virgin Islands that, according to the United States authorities, the condemned businessperson and former Honduran minister allegedly used to launder money from Los Cachiros, the largest drug trafficking cartel in the Central American country.

Nearly two years later, Rosenthal Coello, a member of a large Honduran political-business dynasty, pleaded guilty to attempting to carry out monetary transactions with goods from drug trafficking. He was tried and sentenced before the Federal Court of the Southern District of New York and began to serve a sentence of 29 months in a Florida jail. His uncle, Jaime Rosenthal Oliva, and his cousin, Yani Rosenthal Hidalgo, were also accused in the same case. Further, the United States Department of the Treasury included a dozen of the family’s companies in its ignominious list of Specially Designated Narcotics Traffickers.

Like Yankel, Yani Rosenthal, also a former Honduran minister, ended up pleading guilty to carrying out monetary transactions with goods from drug trafficking and was sentenced to a 36-month prison term. He returned to Honduras in August of 2020 and is currently the Liberal Party’s candidate in the presidential elections that will be held on November 28. Jaime, Yani’s father and Yankel’s uncle, died of cardiac arrest in January of 2019, so U.S. prosecutors closed the case against him.

The labyrinth of offshore companies owned by Yankel Rosenthal and his family, however, was more extensive than what the U.S. Department of Justice revealed at the time.

Yankel Rosenthal, Honduras’ minister of investments from 2014 to 2015, maintained at least six other offshore companies in the British Virgin Islands, some during the time he was a member of Juan Orlando Hernandez’s cabinet, and all of which were active at the time of his arrest in Florida.

The existence of these companies, which had not been made public until now, is one of the findings of the analysis of thousands of internal documents belonging to several legal firms specializing in managing offshore companies in the British Virgin Islands, Panama and other countries, carried out by Contracorriente and the Latin American Center for Journalistic Investigation (CLIP). These revelations are part of the Pandora Papers cross-border investigation led by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ).

Called the Pandora Papers, these documents dating from 1996 to 2020, which are in English, Spanish, Chinese, Greek, Russian and other languages, reveal connections with companies and businesses in more than 200 countries and territories. The collaboration of more than 600 journalists made it possible to investigate hundreds of them simultaneously in 117 countries. An anonymous source shared 2.94 terabytes of confidential financial records with ICIJ, in separate batches over several months, totaling more than 11.9 million documents from 14 offshore service provider companies that create and manage shell companies and trusts in tax havens around the world.

Yankel Rosenthal was convicted by the United States justice system because he tried to facilitate the purchase of a property in Florida with money from drug trafficking and, according to the judicial case built by prosecutors from that country, he resorted to an offshore company to ask for bribes, although in the end he didn’t face charges for that crime. That’s why this discovery raises questions about whether the other offshore companies that didn’t become known until now could have played a role in those shady business dealings.

Archipelagos and crocodiles

On October 6, 2015, just four months after resigning from his government position as minister of investments, Yankel Antonio Rosenthal Coello was arrested in Miami airport when he was going to visit two of his children, who were studying in the United States.

His arrest was the first event in a domino effect that quickly engulfed other members of his family. That same day, the accusation from the prosecutor’s office for the Southern District of New York was made public, indicating Yankel, his cousin, Yani Rosenthal Hidalgo, his uncle, Jaime Rosenthal Oliva, and Andres Acosta, an employee of the Continental Bank, owned by the family, as participants in laundering money from drug trafficking “from at least in or about 2004, up to and including in or about September of 2015.”

The accusation was earth-shattering in Honduras because the Rosenthals— descendants of an electrician who immigrated from Moldova in the 1920s fleeing anti-Semitic violence and who founded the Siga la Flecha store in San Pedro Sula— were one of the wealthiest families in the Central American country as well as prominent political figures.

The three accused family members had held high ranking positions in the country’s government. Yani, the current presidential candidate, was minister of the presidency in the government of Manuel Zelaya (2006-09) and a national legislator. Jaime, Yankel’s uncle, was vice president under the government of Jose Azcona (1986-90), a two-time presidential hopeful and a legislator for the Cortes department. Jaime’s prestige was such that he was featured on Forbes‘ list of the 12 most important millionaires in Central America and German photographer Horst Wackerbarth included him in his celebrated worldwide photographic series of well-known figures sitting on a red couch.

“Starting in approximately 2009, [Yankel] provided financial services to drug traffickers in Honduras, often related to real estate transactions,” reads the prosecution’s presentation before a federal judge in the Southern District in August of 2017, as part of an investigation initially led by prosecutor Preet Bharara, who became famous when Donald Trump fired him.

At the same time, a handful of Rosenthal companies were included on the sanctions list of the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC), which prohibits third parties from doing business with those who are included. Continental Investments in Panama, better known as Grupo Continental, which was a business holding belonging to the Rosenthal family, as well as Banco Continental bank, the meat processing company Empacadora Continental, the financial company Inversiones Continental (also called Grupo Financiero Continental) and three companies in the United States (Inversiones Continental USA, Shelimar Real Estate Holdings II and III) were added to that database, called the Clinton list in some countries because it began during his time in office.

Three offshore companies in the British Virgin Islands which Rosenthal used for his business dealings also came to light in the process: Shelimar Investments Ltd, Preyden Investments Ltd and Desland Overseas Ltd.

Now, within the Pandora Papers investigation, this journalistic team discovered that Yankel Rosenthal has been the final beneficiary or director of six other offshore companies whose existences had not been made public. Some of them existed when he was appointed minister in Juan Orlando Hernandez’s cabinet and all were active until at least 2015, according to internal documents from the Panamanian law firm Aleman, Cordero, Galindo & Lee, better known as Alcogal.

A first company, Esmeralda Investments Holding Ltd, was created on March 22, 2013 in the British Virgin Islands, according to documents from Alcogal.

At that time, Yankel had not yet gotten involved in politics. For 18 years, he had been president of the Chumbagua Sugar Company and for 17 years, a board member of the Occidente bank. Both were companies of the Continental Group, the Rosenthal family holding — including both Yankel’s as well as Yani and Jaime’s branches of the family tree— which came to include another bank, a newspaper, a television channel, an insurance company, a construction company, a cement company, cocoa, banana and coffee plantations— and even a farm with 10,000 crocodiles. After authorities in the United States and Honduras froze the Rosenthals’ assets, according to the BBC, the crocodiles went hungry.

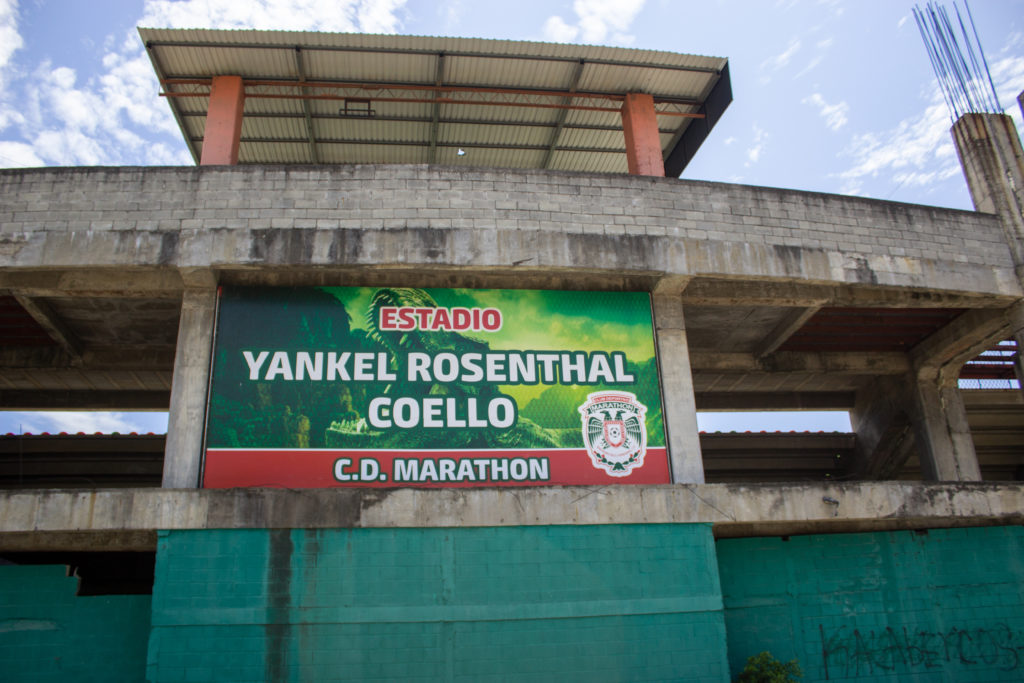

Yankel had also been president and a partner of the CD Marathon football team, whose stadium in the city of San Pedro Sula still bears his name today. The rest of the Rosenthal family also had shares in this sports club, including his cousin Yani.

In Esmeralda Investments Holding, in which Yankel appears as the final beneficiary, his ex-wife, Marcia Cordoba, and his three children, Yankel Antonio, Norma Sofía and Edwin Alberto Rosenthal Cordoba, appear as shareholders.

The personal reference letters to the Panamanian firm were written by Chumbagua Sugar Company, which he presided over, whose accountant certified that he had an annual salary of US$250,000, and by HSBC Bank in Miami, which described him as their client since 1992.

Yankel Rosenthal had a company with a similar name in Honduras: Esmeralda Sociedad Anónima, created in San Pedro Sula in 2008.

In 2015, this company was confiscated by the state of Honduras after an investigation for money laundering. A month before he was arrested in the United States, Yankel presided over a meeting of the company, even though he had resigned from its general administration a year earlier. At that meeting, as a special executor of agreements, the decision was made to donate land to another company called Equipos y Desarrollos S. de R.L., in which Rosenthal Coello had no corporate or administrative ties. However, the general administrator of this second company was his partner in the Consorcio Siglo XXI, of which Esmeralda had 40% of the shares.

In 2010, this consortium won the biggest contract in San Pedro Sula to build bridges, roads and other infrastructure works for a referential amount of 1,845,637,424.82 lempiras (about US$98 million at the time). On October 26, a few days after Yankel’s arrest, the Consorcio Siglo XXI expelled Esmeralda S.A. for having a process of seizure of assets open against it.

In addition to the offshore company Esmeralda, Yankel and immediate relatives appear linked to seven other companies in the British Virgin Islands, either as directors or officers, in the reports that Alcogal sent to the archipelago’s financial authorities. He appears in five of these.

Delven International Limited, created in 1997, lists his mother, Norma, and siblings Norma Johanna, Edwin and Karen as directors. Inversiones Edyasa BVI Limited, registered in 1993, lists his father, Edwin, his mother, Norma Coello, and his brother, Edwin. Ralsen Finance Ltd, registered in 1997, includes his parents and his sister, Karen. Midas Finance International Limited, registered in 2006, involves almost the entire Rosenthal Coello family: Yankel, his parents and his siblings, Norma and Edwin. One more, R.E.R. Holdings Limited, includes Yankel and his brother, Edwin.

According to the reports of suspicious activities processed by Alcogal, Yankel was listed as the final beneficiary, shareholder and director of Esmeralda Investments, shareholder and director of RER Holdings, shareholder of Ralsen Finance, director of Inversiones Edyasa BVI and officer of Delven International and Midas Finance International.

When Yankel was a government minister between 2014 and 2015, at least Esmeralda Investments was active, which he was obligated to declare to the treasury in Honduras. However, since the records of assets and business interests of public servants are not published, it isn’t possible to find out if Rosenthal Coello complied with this legal obligation. The Honduran media of this alliance, Contracorriente, filed an appeal before the Constitutional Chamber of the Honduran Supreme Court of Justice to open this information of public interest, but as of the date of publication, a decision had not yet been made on the matter.

This journalistic alliance tried to contact Yankel Rosenthal on four occasions since September 17, twice by email and once via a message sent to his active personal Facebook account, including nine detailed questions that we wanted to ask him. We also wrote to the attorney who represented him during the trial in the United States. At the time of writing, Rosenthal had not responded to our requests for an interview.

The offshore factor in the trial against Yankel

Initially, the Rosenthals’ network of companies— including their three offshore companies— figured prominently in the prosecution, but gradually lost its prominence during the judicial process.

In the end, after negotiating with the prosecutor’s office of the Southern District of New York, Yankel pleaded guilty on August 29, 2017 to a single count of attempting to purchase an asset with money from drug trafficking in Florida. In his written statement before the federal court, the former minister defended himself. His lawyers said that not all the steps had been taken for the purchase of the three properties in the Doral area in Florida and that the “gulf is massive between the eleven-year-long money laundering and political bribery conspiracy described by the government in the initial indictment on the one hand, and the Attempted Doral Transaction.” However, he admitted to the U.S. court that he knew that the lawyer who had sought him out had clients who were drug traffickers, that he had not investigated the origins of the money for the real estate business deal arnd that he was aware that they were probably illicit.

“Yankel is acutely aware of the draconian consequences that resulted from his terrible lapse in judgment … He intends to avoid any perception of involvement or social relationships with wrongdoers, especially narcotics traffickers,” concludes the memorandum presented by his lawyers before the sentencing, in which they protested what they described as an excessive punishment.

As a counterpart to that agreement, the prosecutors presented other accusations against him and with that, Rosenthal Coello avoided going to an adversarial and public trial. The U.S. authorities managed to secure a conviction and a prison sentence for Yankel, although it meant that much of the body of evidence available to the Justice Department did not come to light.

The information that would explain what Yankel used the trio of offshore companies that the investigators detected in the British Virgin Islands for was therefore buried by the agreement. On the same day he was arrested, an agent from the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) asked him about them during the first interrogation, according to a transcript that the prosecutors in charge of the case attached as evidence to the judge in 2018.

That day, when Rosenthal tried to persuade the anti-narcotics agents that they were mistaking him for someone else, one of them replied that they had a recording of him and that they knew about many of his companies. One by one, he was asked about Shelimar, Preyden and Desland.

“Here is one thing I know you did for a fact,” Yankel was told by “Agent-1,” according to the transcript of the conversation that is part of the file. “You would receive drug trafficking profits. You would pay the players and coaches of your soccer team in drug trafficking profits. Then essentially you would take drug proceeds, you would put them into your Continental bank and then you would get bank checks from Continental, ship them up to Shelimar, and then you would have payment to the soccer team come back down to Shelimar.”

And the agent continued with his accusation, “So you’re basically using the soccer team to wash drug proceeds for your guys. I mean, you can find out in court. That’s what we, that’s one thing we know you did,” added the DEA agent.

“That, that, you’re completely confused about that,” Yankel replied.

“I’m not confused at all,” his interrogator retorted.

A noticeably flustered Yankel tried to persuade him once more that his information was wrong. “I, I, I know because … I’ve never taken any, any, uh, if you want to call it dirty money into my, into my accounts. I don’t know … I know these people more socially than I have, than doing business with them,” he told them. “Hey, if you want me to be honest.”

The company about which the U.S. agents appeared to have the most detailed information was Shelimar Investments.

On the day that Yankel pleaded guilty, the Justice Department publicly indicated that the former minister had asked a U.S. oil company that was interested in investing in Honduras for a bribe four years ago.

According to the prosecutors, in April of 2013, Yankel sent an email to the company whose name was withheld, which the legal file calls Company-1. “[L]ike I told you a couple of years ago, sadly in our countries politicians expect colaboaration [sic] to their campains [sic] when approached for a business proposal, I have all the confidence in this friend he has power now and will have much more later on (Nov 2013), can he count on a contribution for his campain [sic] and at the same time with the unde[r]standing he will help with the exploration and ambient permits requi[r]ed?” his email said, according to the Justice Department.

In September of 2013, five months after the email from Yankel and two months before the presidential and legislative elections in Honduras, an executive from the U.S. oil company replied that they were willing “to contribute to your friend’s election for president,” as recorded in the statement from the prosecutors. He then allegedly wrote a US$100,000 check to the offshore company Shelimar Investments, also according to the Department of Justice.

U.S. prosecutors never specified which “friend” the oil executive was talking about. A month later, with less than four weeks to go before voting, Yankel publicly announced his support of the campaign of the president of the National Congress at the time, Juan Orlando Hernandez. “I’m grateful to Yankel for the support and his demonstrations of confidence. I hope his cousin Yani in San Pedro Sula isn’t going to scold him,” Hernandez thanked him, referring to the fact that Yankel’s cousin had been a pre-candidate for the rival Liberal Party and had lost in the primaries a year ago. “I have been quietly supporting Juan Orlando from within the National Party, but since my cousin Yani was a candidate for the Liberal Party, I didn’t make it public,” Yankel explained that day.

In late November, Hernandez won the presidential election. In January, when he took office, Yankel Rosenthal Coello was appointed to his cabinet as his investment minister.

Although the prosecutors emphasized these alleged payments, in the end, that information did not appear during the trial and Rosenthal Coello was not charged for it. And that has been the former minister’s defense. After serving his sentence, Yankel responded to criticism from his former boss, Juan Orlando Hernandez in a public letter, saying that he “was never charged, much less convicted, of drug trafficking or any related crime.”

“I was convicted and served a 23-month sentence for an attempted crime, in other words, a crime that wasn’t carried out, in which it was fully established that I never received sums of money from any criminal group. Proof of this is that all the assets insured abroad were fully returned to me,” he wrote from what he called a “painful self-exile” because of the “persecution” against him.

The end of Rosenthal’s offshore companies

“If we find, are informed by any source, or become aware by any means, of negative information involving a company or client, including suspicions of criminal activities, their involvement in a criminal investigation, or the existence of a conviction, we proceed with the appropriate course of action, ranging from obtaining disclaimers to resigning as Registered Agents and/or filing SARs, as applicable on a case-by-case basis.” This was the answer that Aleman, Cordero, Galindo & Lee gave to questions asked by ICIJ about what due diligence they do on their clients and how they ensure that those who are politically exposed are not using these paper companies for possible illicit activities. Although Alcogal did not respond regarding specific cases, their documents show that this is what the Panamanian firm did in Yankel’s case.

His arrest in Miami, probably added to the public mention of three of his offshore companies in the United States Department of Justice indictment, and set off alarm bells at the firm that had managed them.

On October 8, 2015, two days after his arrest, Alcogal sent a suspicious activity report (or SAR, in legal jargon) to the British Virgin Islands Financial Investigation Agency, as shown by internal documents from the Panamanian firm.

In that report, compliance officer Blondell Challenger, from the Panamanian law firm, notified the archipelago’s financial authority that it had terminated its business relationship with four companies in which Rosenthal appeared as the beneficial owner, including the three included by the U.S. Department of the Treasury on the list of sanctions and one more that it had not detected (Esmeralda Investments). As the motive for the firm’s decision to resign as a registered agent for these companies, Alcogal cited the fact that Rosenthal had been arrested and implicated in the alleged criminal activities of drug trafficking and money laundering.

A month and a half later, on November 20, Alcogal sent a second suspicious activity report to the BVI’s financial authority, informing them that the firm had identified the other five companies in which Yankel appeared as a director or shareholder that this investigative report reveals. The SAR also identified two other shell companies linked to his relatives and one more that might be attributed to relatives but which Alcogal wasn’t sure of.

Citing the most recent developments in the court case, which included Yani’s arrest and possible trials against the family patriarch, Jaime, in both countries, the Panamanian firm added to the report the suspicion that its clients were involved in organized crime. Alcogal wrote.

In addition to the five companies described in this investigative report, Alcogal cut its ties with two companies to which Yankel’s relatives were linked: Midas Investments Overseas Ltd, which was connected to his brother, Edwin Rosenthal Coello, and his niece, Daniella, and Frisbold International Limited, which was linked to Cesar Rosenthal Hidalgo— Yani’s brother and Yankel’s cousin— and Cesar’s Costa Rican wife, Erika Seevers.

Ironically, Alcogal also canceled another company called Spring Rosen, linked to a Marcos and a Susana Rosenthal, who don’t appear to have any ties to the family and may not even be Honduran.

Unlike his presidential candidate cousin, Yankel Rosenthal has kept a low profile since he got out of jail in Florida. In mid-August of this year, however, he reappeared in San Pedro Sula to encourage his football team, Marathon, in a game against Nicaragua’s Diriangen for the CONCACAF League at the stadium that still bears his name. They won 2 to 1.

1 thought on “After Honduran politician Yankel Rosenthal’s marathon in the courts, new offshore businesses come to light”

The Rosenthal Family is dirty and corrupt! They have taken advantage systematically of the vulnerable and needy to enrich their coffers! His uncle Jaime was the precursor and the leader of the corruption rollercoaster!