I am on the other side of the border that around seven thousand Hondurans are trying to cross. I am writing about that exodus of refugees that walks and breaks through fences, that gathers together thousands on a border bridge in Guatemala or in the Suchiate river and that faces police repression when they cross and enter Mexico. It is also possible to talk about the Migrant Caravan from within the United States, with those who succeeded in crossing the border almost alone, away from cameras and from strident threats. From here I see other walls that face the refugees who succeeded in arriving when migration was not a river. From here, with the stories of those who went ahead, I can hear why the river of people is crossing Mexico now.

It is being called the “Migrant Caravan.” This flow of people that at first, for decades, filtered through drop by drop, now has turned into a gush of water bursting through a crack in the wall of a dam. This rush has provided evidence of the cracks in a state that failed to protect its people.

Text: Jennifer Ávila

Photo: Alejandra Rincón

Waleska is under surveillance. A device on her right ankle identifies her as a person who has broken the law. She will be tied to this monitoring bracelet until her petition for asylum advances to a new stage, if it does advance. Waleska, with her two-year-old child, fled Honduras for the United States in the first caravan of Honduran migrants organized in May of 2018. At that time there were 2,500 Hondurans seeking asylum. She was detained in a prison, pleading not to be separated from her child, and now survives in a sanctuary state, where pro-migrant organizations help her during a wait that could last 600 days.

“This is like being a prisoner, too, you can’t do anything like this. If the battery on this thing runs low, it talks to you,” Waleska says and laughs at her own predicament, while cooking some pastelitos with Susana, another asylum seeker, an 18-year-old Guatemalan who arrived just a few weeks ago with her four-year-old daughter. Waleska and Susana support each other. Both wear on their right ankle the tracker that the Intensive Supervision Appearance Program (ISAP), a private company that has contracts with ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement, by its initials), calls an “electronic monitoring device.” They go to scheduled interviews, and ISAP makes visits to the houses that they have given as permanent addresses even though their circumstances don’t allow them to establish themselves in a single place within the sanctuary state.

As long as Waleska and Susana have to wear the device, they cannot get a work permit, which functions a form of pressure to get them eventually to go back to their countries of origin, not being able to survive in the United States, either, without work.

Waleska fled from a community under siege, like many in the north of Honduras, a drug corridor to the United States. In addition, she faced the threat of the privatization of the river that runs through her community for the construction of a hydroelectric project. Waleska resisted as part of the community organization. She was put in prison for protesting and was afraid when the threats began to grow in force and an activist of her organization was assassinated during the post-electoral crisis in January of this year. The case of the assassination still has not been solved.

In Honduras, around 100 concessions for the production of hydroelectric energy have been approved, despite the resistance of local populations. After the assassination of the environmental activist Berta Cáceres in March of 2016, Honduras was catalogued by the British non-governmental organization Global Witness as a dangerous country for defenders of human rights and the environment. The territorial concessions have generated conflicts and forced migration.

After the elections of November 2017, from which Juan Orlando Hernández emerged as reelected, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) documented 22 assassinations perpetrated by state security forces who shot to kill during the protests: The illegitimacy of a president who got himself reelected despite the constitutional prohibition, in elections stained by fraud, has generated more violence and repression against the opposition, and this also has generated forced migration.

Waleska did not flee for one reason only. She fled from the violence generated by the narco-trafficking in her community that has exterminated entire families. From the threats for being part of the resistance defending natural resources. She also fled from the violence that she suffers as a woman, in a poor community without opportunities, from violence at home, where she suffered attacks by her ex-husband, from poverty while having to provide alone for her seven children.

Waleska has had to fight on many fronts, so coming with the May caravan and being half prisoner, half free, is better than having stayed.

“Coming by caravan was much safer. People were friendly. I decided to go before the caravan was talked about, I got as far Tapachula and from there I waited for it after I saw the news. We went through Mexico asking for help and managed to keep going in that way. The tough part is arriving here and getting put in the icebox (detention center for migrants) and seeing how they separate mothers from their children, you have to hang on to your loved ones so they don’t take them away,” she recounts.

Susana, for her part, at 18 years old already has a four-year-old daughter. She fled her town in Guatemala because of a threat from her brother-in-law, involved in narcotrafficking. She asks that the name of the town not be published, she is afraid.

“The police get money from them, twice I tried to file a complaint and they didn’t do anything. My daughter is tormented. If you ask her why she is here in the United States, she says it’s because there were gunshots in her house,” Susana recalls, while she breaks down in tears.

Susana was 14 years old when she had her daughter, and she suffered a serious infection due to medical negligence when they performed a Caesarian section. She did not file a complaint. Silence has been a rule of her life.

Waleska and Susana tell me their stories in the house of an Oregon citizen who has put a sign in the yard that says: Vote NO on Measure 105. Without the hospitality of people like him, Waleska, Susana, and other asylum seekers would not be able to survive alone and limited by ICE.

In November, the United States will hold midterm elections and there in Oregon, which for 30 years by law has been a sanctuary state, there will be a ballot measure to ask the voters whether they want this law to continue in effect in their state or not. Removing the status of being a sanctuary state would imply that the local security forces might support ICE in its hunt for migrants. A variety of civil society groups have organized to raise the awareness of voters in order to keep this measure from being approved.

For now, for Waleska and Susana, Oregon is a good place to live, even though little by little ICE expands its presence through contracts with state detention centers and ISAP.

Robert Brown of the Interfaith Movement for Immigrant Justice (IMIrJ) affirms that the Trump government has obliged them as civil society to rethink the concept of sanctuary.

“Our concept of sanctuary is not physical, but omnipresent. There are many ways of welcoming migrants. From support in the form of shelter to political actions,” Brown says after a meeting with the staff of his representatives in the House and the Senate: the Democrats Jeff Merkley, Suzanne Bonamici, and Senator Ron Wyden. Brown came to talk about the migrant caravan and to ask his representatives to sign a letter demanding that the government of Donald Trump pressure the government of Honduras to investigate the threats against journalists, human rights defenders, and international accompaniers. For Brown, it is clear that the conditions that generate the exodus of migrants exist by means of the governments of the Central American countries with the support of the United States.

“We connect the struggle against the NORCOR contract with ICE via Gorge Ice Resistance and the opposition to Measure 105, which is confusing and ultimately means a country that does not like migrants. It is sending a mistaken message, it would make our communities less safe because the security forces would concentrate on criminalizing migrants instead of on the problems of the community,” adds Brown, who has participated in protest actions which in his city have gone to the point of civil disobedience: this year about 20 people were arrested for blocking the entrance to the ICE office in Portland. And the movement for justice IMIrJ helped with travel tickets for migrants going to states where they have family, as well as with food and legal support.

In 2017 alone, ICE devoted almost 3 billion US dollars to fund the system for detaining foreigners whose cases are awaiting resolution by the tribunals or whose deportation has already been decided, according to a report by the BBC.

These contracts benefit private companies that have contracts with the U.S. penitentiary system. Every migrant detained raises the costs and increases the contracts.

Voting will take place in the United States on the 6th of November. In the “midterms” a third of the senators and all (435) of the members of the House of Representatives, which turns over every two years, are elected. These elections also allow the citizenry to express their position with regard to public policies and to establish the balance of power between the political parties in the institutions of the state. Thirty-five of the 100 senators, the 435 members of the House of Representatives, and 36 of the 50 governors in the country will be elected now. Up until the middle of October, the opinion polls did not favor Trump’s Republican party, but current events concerning migration might help their numbers.

The arrival of thousands of Central Americans at the border is seen as a threat to sovereignty – as Vice President Michael Pence tweeted and in tune with the anti-migrant campaigns launched by Trump’s party, it serves as the perfect storm for closing off the country in the face of a refugee crisis. In the case of Oregon, with Ballot Measure 105 which would eliminate the sanctuary state.

Fleeing the gang

Jorge Rodríguez is the pastor of the Lutheran Church in a city in Oregon. Rodríguez, Honduran, organized a discussion with people from his community, the majority from the U.S., to talk about Honduras. One of those at the meeting was X, a 24-year-old young man who just two weeks previously had gotten out of the Sheridan Federal Correctional Institution, supported by a collective of volunteer lawyers known as the Innovation Law Lab, a project to support migrants.

X is seeking asylum in the United States because he fled a threat by the Mara Salvatrucha in Honduras.

“I got threats from the gang, (they demanded) that I spy on lawyers who entered and left the Attorney General’s office since I worked in a nearby street. Since I was little they asked me for favors because I lived in one of their territories, I always refused,” X recounted in the presence of a volunteer from the Law Lab.

Subsequent to the approval of new federal regulation as a directive of the chief of the U.S. Department of Justice, gang violence is not grounds for soliciting asylum in the United States. Nonetheless, criminal control of neighborhoods and communities in Honduras has become one of the most urgent reasons for fleeing, as in the case of X.

Although in 2017 Honduras no longer was ranked at the top of the list of the most violent countries in the world, and while the Observatory of Violence of the National Autonomous University of Honduras (OV-UNAH by its initials in Spanish, el Observatorio de la Violencia de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras) supports the data on the reduction of violence provided by President Juan Orlando Hernández, affirming that the index of homicides went down by 12 percent this year, there were local increases in specific communities. Honduras ended 2017 with a rate of 43.6 homicides for every one hundred thousand inhabitants, according to the Observatory.

The public safety policy of Juan Orlando Hernández has been repression and militarization. In 2012, Hernández created the National Anti-Extortion Force (FNA by its initials in Spanish, Fuerza Nacional Antiextorsión), which in July of 2018 turned into the National Anti-Gang Force (FNAMP by its initials in Spanish, Fuerza Nacional Antimaras y Pandillas), a force specialized against the crimes of illicit association and extortion. Although every week the FNAMP displays people they have captured and anti-gang operations, communities continue to experience conflicts and have identified this force as another actor in the violence that they suffer.

Joaquín Mejía, Doctor of Human Rights in Honduras, affirms that two factors indicate that Hernández has created “security populism:” the militarization of security and state institutions and “hyperjudicialization,” that is, the rapid approval of laws and penal reforms regarded as new actions against crime, such that the government can present itself to the public as acting with an iron fist.

“The security tax, 170 million lempiras [close to 7.4 million UD dollars] a month that are collected specifically for this purpose, is used to strengthen the police and the armed forces. According to their numbers, 41.21% goes to the military, 41% to the police, and then only 5.66% to prevention programs, 5% to the Attorney General’s office, and 2.85% to the judiciary. This is serious in a country where, according to the index of failed states, Honduras is considered a state at risk, because the population lacks its basic rights because all of the funds are diverted to benefit the armed forces. The penal system is used to criminalize, and this obliges people to leave,” Mejía affirms.

So young people like X choose to flee instead of filing complaints.

X already had a Mexican visa, but even with that, it was not easy for him to cross through Mexico. He lived there for a year and worked in hostels helping hundreds of Hondurans fill out their solicitations for refuge. But the violence and the lack of a job that would permit him to live with dignity pushed him to continue north.

In 2017 alone, 130,500 new petitions for asylum or refuge were filed by Central Americans fleeing to Mexico or the United States, 38% more than in 2016 and more than 11 times the solicitations presented in 2011, according to a report by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). In 2011, the state of Honduras recognized forced displacement as a problem and as a result, the UNHCR office was installed to attend to that along with the state.

“I liked Honduras a lot, I liked the art and made piñatas for micro-businesses. I even met Berta Cáceres when they called me to paint murals. I did tattoos and a few times I refused to tattoo numbers or letters. But you can’t live there. Here I was in prison and it’s not easy, but being in Honduras is worse, there’s no comparison,” X says emphatically. Now he hopes that his petition for asylum will advance and that he will be able to obtain a work permit. In the meantime, he is being tracked and his liberty is conditional. In Honduras and now in the United States, X’s liberty has always been conditional.

How did the migrant caravan turn into an avalanche?

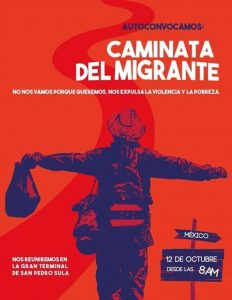

On October 12th via social media, a poster circulated that called for people to leave the country together, everyone who wanted to. A convoking that called for people to meet at the bus terminal in San Pedro Sula at 8 o’clock in the morning. The political message was clear: “If this president stays, we go.” But there was a miscalculation, something that had not been foreseen: the desperation of thousands of Hondurans, who more – much more – than their political ideology, are hungry, scared, and want to survive by fleeing.

Going in a group was an opportunity that sent a powerful message but also offered protection. The invisible migrants decided to make themselves visible, something that affects the business of the coyotes and that is stronger in the face of walls.

But Bartolo Fuentes, former deputy of the LIBRE party (Libertad y Refundación, Liberty and Refoundation), to whom was attributed the organization of the caravan, affirms that he only supported the people, that his struggle is on behalf of

migrants and that he would never seek either economic or political advantage from a situation like this. The government of Honduras is utilizing rhetoric that accuses the opposition of tricking the migrants in order to use them for political purposes; and the U.S. embassy in Honduras, via the Chargé d’Affaires Heidi Fulton, has supported this government rhetoric.

Fuentes feels threatened. He was detained in Guatemala when he accompanied the caravan, sent back from that neighboring country. Nonetheless, other members of the political opposition belonging to the LIBRE party do not deny that the convoking might have come from them, and that some journalists were informed.

“If they are going to do something to me, well I’ll face it, in any case, I’ve lived enough,” said Fuentes, for his part, this week in a forum in El Salvador with friendly international participation.

Various people have been targeted as those responsible for the caravan. From Bartolo Fuentes to George Soros, the U.S. multimillionaire and benefactor who founded the Open Society Foundation, accused of being the financier of the caravan for leftist political reasons. Also the government of Venezuela.

For his part, President Trump has railed against the migrants in the caravan, affirming that people from the Middle East, related to ISIS terrorism, have infiltrated it. Trump threatened to end aid to Honduras if the government didn’t return the people to their own country.

“Take your camera, go into the middle, and search. You’re going to find MS-13, you’re going to find Middle Eastern, you’re going to find everything. And guess what? We’re not allowing them in our country. We want safety,” was what he said to the U.S. press.

Responding to the pressures, Juan Orlando Hernández said in a press conference that he had created a new program of agricultural reactivation in order for the returning migrants to have work. A 27 million dollar program. That was in a press conference while he was closing the border with Guatemala at Aguas Caliente.

“The members of the Migrant Caravan who decide to return can count on vouchers, subsidized housing, agricultural projects, employment in public works, credits for micro-businesses, and grants for their education,” he informed.

On October 23rd in Honduras, an internal caravan left from the north of the country headed for the presidential residence to raise its voice on behalf of those who already were traveling through Chiapas, for the sake of the exodus not continuing to be criminalized and to reinforce the political message: the president is the one who should leave.

But the river of people on the road toward the border of the United States wasn’t thinking about that. Despite the closure of the border with Guatemala at Agua Caliente for a week, several groups of migrants already had left to join the caravan traveling through Mexico.

***

Marina’s brother is coming in the caravan. “Help me ask about him, I haven’t heard anything for several days and I’m scared,” she asks me. Marina is 17 years old and lives in a hostel for minors who are migrants unaccompanied in the United States. The adolescent fled alone a few months ago and now her 15-year-old brother has taken advantage of the caravan and also fled the violence in their home and the indifference of the authorities in a town controlled by narcotraffickers.

Marina feels enormous nostalgia, her eyes fill with tears when she describes her town: a lovely place but governed by narcos. Violence is what Marina knows best, not only because it is in the street, but also because it is in her home, and the institutions that are supposed to protect her are contaminated.

“When I was 10 years old I began to look pretty, you know…And my stepfather began to touch me in my intimate parts, and I refused him. My mother always washed other people’s clothes and I sold donuts in the street since I was eight years old. My stepfather was very violent, I remember when my mother was pregnant with my little sister and he was threatening her with a broken beer bottle, telling her he was going to get the baby out of her belly. My mommy just cried, the police nabbed him but they let him go after 24 hours, he always managed to get out,” she relates.

Marina barely made it to the sixth grade and now in her new household, a hostel where she has classes in dance, swimming, and writing, she has begun to write her story in a student magazine.

“He tried to kill me. The police never did anything. It was hell,” Marina says and with a trembling voice tells me that she misses her town, the thermal waters where she had fun with her girlfriends. Marina misses the country that I had described – in the discussion that Marina attended – as a fractured state, that people do not want to leave but where they are without any alternative.

“My brother is coming for the same reason, because he had to make himself disappear, for something like two years he had disappeared because my stepfather had left him to sleep outside,” said Marina, who went to the discussion at a church in Portland wearing a press pass that identified her as part of the student magazine.

That night Marina raised her hand and asked to speak after my presentation and got as far as saying: “I come from Honduras, and I’m from a town where there’s violence, where it’s the narco who governs,” before she broke down in tears.

Domestic and gender violence now no longer are grounds for soliciting asylum in the United States, either, nonetheless, cases such as that of Marina, a minor with verifiable fear, show that the fight continues to be recognized as survivors who cannot return to the same situation that they fled, because they could be killed.

According to the Center for Women’s Studies (CEM-H by its initials in Spanish, Centro de Estudios de la Mujer – Honduras), this year to date more than 165 femicides have been recorded, while the National Commission for Human Rights in Honduras (CONADEH by its initials in Spanish, Comisionado Nacional de Derechos Humanos en Honduras) this year has received more than 2,200 complaints of domestic violence from women, who generally turn to this body because they have not gotten an answer from the authorities who are supposed to take responsibility.

Marina talked for barely two minutes by telephone with her brother in a call that he made to tell her that he is okay, that he had survived the attacks in the caravan, that soon they would reunite. The days go by slowly, the risk grows along the way the closer they get.

***

In the kitchen where Waleska and Susana are trying to cook Honduran food, the chatter moves from tough memories of when they feared they would be separated from their children in the detention centers to laughter about the food in the U.S. and what they cannot find in the supermarket. They talk about the difficulty of living in a foreign country, tied to an ankle bracelet, until they reflect that in that country it is true, that they cannot return to their countries of origin because they would be killed.

“This process is burdensome, my sister even takes pills for her nerves. If they deport me I don’t know what will happen to me. There is no hope in the country, before there wasn’t so much, so much power of the narcos. With my sisters we went to roast fish on the beach, enjoying ourselves, now you can’t do that, we prefer to be shut up in our houses,” Susana says, trying not to give in, stressed and trying to hide the electronic bracelet that weighs on her steps.

Waleska looks at her and tells her: “If you go back it’s the end, the same as for me.”

Waleska’s son and Susana’s daughter play together in the leaves that have fallen from the trees in autumn in the Oregon cold. Their mothers watch them through the window while they talk about the caravan, about the thousands more who are trying to reach the destination where they have already arrived, to cross the border of the United States. And they think about those who remained at home, Waleska thinks about her other children who remained in their community at risk.

***

The caravan continues on its way and already there has been a death as a result of police repression. Dennis Mejía, 26 years old, died after being hit in the skull by a rubber bullet in repression at the border at Tecún Umán, where a new wave of migrants tried to cross the Suchiate River and enter Mexico. The caravan is separated into several groups and now waits in Oaxaca, with 2500 kilometers to go to arrive at the border with the United States. Some 2,700 migrants, the majority of them women and children, entered Mexico seeking refuge in that country and several hundred more have returned to Honduras with the support of the Honduran government, the government speaks of three thousand returnees. More than six thousand continue walking and an additional 200 from El Salvador are joining.

“My five-year-old daughter was disappointed, my father had said that she would come in this new caravan and she already believed that she would get to see her mother again. My father had an accident before the caravan could leave and he broke his foot, so now they are not coming. I believe that is better, I would go crazy seeing what they are doing at the borders, shooting gas at them, beating them up. I don’t think that I could stand seeing that from far away,” Waleska recounts while she finishes eating a pastelito that she cooked.

“They really are like the ones in Honduras?” she asks, as if needing to taste the flavor of the country that she loves but that expelled her.

Note: This account was written thanks to a tour organized by Witness for Peace in the northwestern United States. More details here: http://witnessforpeace.org/northwest-speaking-tour/