Journalists and communicators have denounced persecution and threats for covering environmental crimes in Santa Rosa de Copán, a city in the midst of a water shortage. Authorities still allow illegal logging on nearby forests, an activity that affects the city’s water sources.

Text: Allan Bu

Photography: Amílcar Izaguirre

Cover: Persy Cabrera

Yalile Dubón is a journalist based in Santa Rosa de Copán, department of Copán, where she led a news outlet as reporter, producer and presenter. She had agreements with local businesses to run advertisements, and her program was also broadcast on another news outlet in La Entrada, a city about 42 kilometers north. But she was unexpectedly told that she had to vacate the offices she was leasing. “We had a good start; our programs were broadcast on two media outlets,” she says. But everything changed when she started denouncing illegal pine logging on the outskirts of Santa Rosa de Copán.

According to sources interviewed by Contracorriente, the forests are the only means the city has of replenishing groundwater and avoiding the water table – the municipality’s main water source – from falling. However, its level has been decreasing over the years.

Water shortage is nothing new in Santa Rosa. Twenty years ago, residents in some neighborhoods had access to water twice a week, but it’s worse now, and most neighborhoods have access to it for two hours every 15 or 20 days.

It is clear to Yalile that denouncing real estate developers who have extracted resources in the region made her a target, and this has severely affected her chances of continuing her work as a television reporter. But she is not the only one. Jorge Posadas, another journalist from the Copán department, has documented environmental crimes in areas of valuable forests that replenish one of the few water sources in Santa Rosa. He has also been persecuted and threatened for his journalistic work.

Jorge faced legal actions for posting a photo of a municipal employee on social media. He posted the photo because the employee was filming him while doing journalistic work in an area where trees had been logged. He was summoned before a judge, but he had received legal advice from the Association for Democracy and Human Rights (Asociación por la Democracia y Derechos Humanos – Asepodehu). Although Jorge walked free from the proceedings, he believes the legal actions were taken by the same people who have threatened him for covering environmental crimes in the area.

He and his colleagues received threats after reporting the environmental damage caused by tree logging. They have been followed while driving or walking. “A colleague was followed for a month,” a journalist who also received threats said, “he had a nervous breakdown and was sent to hospital.”

He is one of the first journalists who denounced deforestation in an area close to El Carrizal village where businessmen are planning to build housing developments. According to environmentalist Ramiro Lara, this forest is adjacent to La Hondura, a source that supplies water to 30 percent of the population in Santa Rosa. This is an area where 6.7 hectares of land have already been deforested. El Chorrerón, a spring where communities obtain drinking water, is also dependent on the forest.

Jorge acknowledged that he and his colleagues are afraid of reprisals for filing complaints because there is no trust in the Attorney General’s Office and other public institutions. However, he filed a complaint with Honduras’ National Human Rights Commission (Conadeh) in response to the threats he had received. He is also enrolled in the Protection Mechanism for Human Rights Defenders and Journalists. As part of this program, areas where journalists under threat of violence live are patrolled, and they also have id cards which they can show to the National Police if they find themselves in danger, Jorge explained.

Contracorriente visited the Attorney General’s Office in Santa Rosa de Copán to inquire about complaints of environmental crimes, but a public official bluntly said that this information cannot be provided without an authorization, and his superior was not in the office at the moment.

Both Yalile and Jorge feel vulnerable. She had a nervous breakdown due to the threats and was forced to seek medical help. Although she has filed complaints with representatives of the protection mechanism and has been in contact with them, she knows she is in an extremely vulnerable situation; “I haven’t had any protection,” she says.

People who work in the media have told her to stop reporting on deforestation because it’s dangerous. Due to the lack of protection she and her colleagues feel, they are constantly in touch on social media until late at night; it’s a way of not feeling lonely, Yalile says. She frequently talks to five journalists who also received threats after reporting on environmental crimes. “I trust in God because I have faith, but there’s not much I can do,” she adds.

Attacks against Yalile, Jorge, and other journalists became harsher after exposing that the municipal council approved a change of land use in a pine forest called Cerro Partido, which is located alongside the highway that leads to Gracias, department of Lempira. “They’re very upset. I don’t know who stands to benefit from this,” Yalile said in a phone conversation.

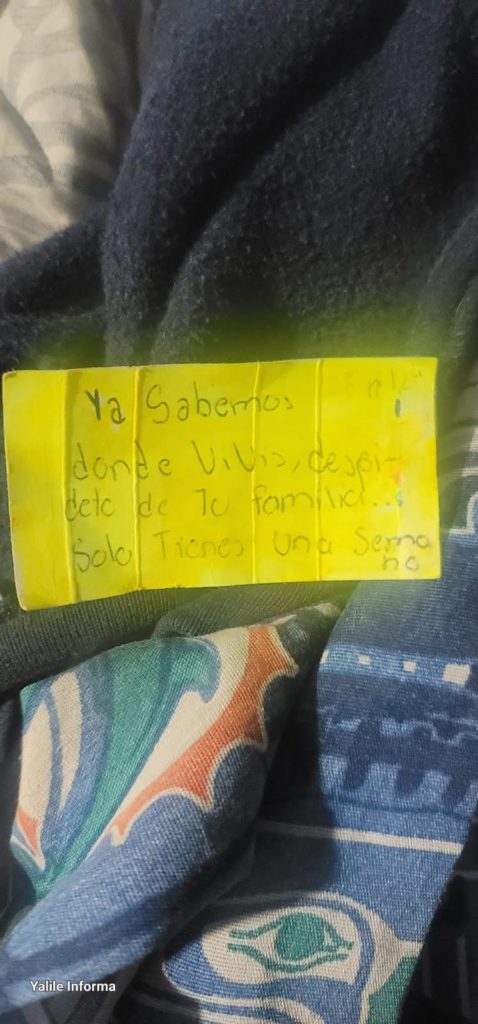

“We have been defending the environment. And they have told us: ‘if you don’t delete that, you know what’s going to happen to you.’ They use fake accounts, but I think the municipality is behind all of this. I’m worried,” said Yalile to a local news outlet in Santa Rosa de Copán in early 2024. On January 24, when Hondurans celebrate Women’s Day, Yalile’s mother found a yellow paper with a message on the front door of their house. It read: “We know where you live.”

Yalile received threats from unknown or fake accounts after releasing a video of the son of Mayor Aníbal Erazo Alvarado being detained for illegal possession of weapons. Police released him a few hours later and issued a statement saying that the weapon belonged to a friend of the detainee.

Mayor Alvarado is a friendly man. His mother became famous for cooking pork in artisanal ovens. He was first elected as mayor in 2009, when Porfirio Lobo Sosa was elected as president, and has been reelected three times since. In the last primary election, Alvarado supported Yani Rosenthal, presidential candidate from the Liberal Party. Although Rosenthal was defeated, Alvarado was reelected as the mayor of Santa Rosa de Copán.

Councilman Eduardo Elvir says Mayor Alvarado has eliminated the mechanisms of citizen participation to have control of decision-making. “He thinks he owns Santa Rosa de Copán,” he added.

Yalile has denounced the persecution she’s facing on several news outlets; she thinks the municipality of Santa Rosa is behind it. Due to the persecution she can no longer work as a reporter because she was forced to leave the local channel and close her business in the local market where she sold beauty products.

A city facing a water shortage

Santa Rosa de Copán sits on a plateau which is why there are no water sources on the surface. The municipality – through the agency of Empresas Municipal de Aguas – has tried to obtain water from the Higuito River, which flows a few kilometers below the city, but efforts haven’t been successful because while it’s a fast-flowing river, it’s an onerous task to produce potable water.

Maynor Pineda, specialist at Honduras’ Institute of Forest Conservation (ICF), said, “Water sources on the surface are scarce due to the high altitude. A project to obtain water from the river was set in motion, but it’s expensive because the water becomes murky in winter.” He explained that although it’s difficult to analyze this case, groundwater is decreasing, per estimates: “The water table decreases by 43 centimeters in Santa Rosa de Copán every year. Aquifers can only be replenished by rainwater as it filters through soil, sediment, and rocks. And if deforestation continues because of population growth, there is no other way to replenish aquifers,” he explained.

Pineda asserted that by 2015 the municipality had drilled 16 wells to supply water to the city, but by this time the same number of wells had been drilled to provide water to private hospitals, shopping centers, hotels, gas stations and businesses that sell it. “It’s profitable to own a water tank truck and sell water to people who consume large amounts of it,” he said.

Well drilling is a way to mitigate water scarcity in Santa Rosa, but Pineda says there are signs that the groundwater is being depleted at an alarming rate because of overexploitation, and the municipality, under Mayor Alvarado, “shouldn’t allow further well drilling for private use.”

Eduardo Elvir, councilman in the municipality of Santa Rosa from the Libre Party, recalls that a study was conducted in 2009 to map areas for developments and land use change. He says this initiative was backed by Alvarado, but there were no efforts to follow up on its progress. “Urbanization has a major impact on forests because it generates changes in land use. We have lost about half of the plots of land suitable for forestry,” he said.

Elvir explained that areas suitable for forestry surrounding Santa Rosa are privately owned, so there’s a land conflict. He accuses Mayor Alvarado for not being capable of balancing private ownership and the population’s well-being “mostly because of business interests.” Urbanization plans are delayed by the municipality, forcing interested parties to seek the mayor, he added, “this is how negotiations begin.”

Elvir pointed out that highly illegal acts against democracy take place during sessions of the municipal council and thinks this occurs in every mayor’s office around the country. “Municipal authorities are major environmental plunderers. There’s no control, and the municipal council and mayors’ offices are behind many environmental crimes. I have to speak up,” he said.

Carlos Henríquez, social and environmental manager in the municipality of Santa Rosa, denies that water scarcity in the city is caused by uncontrolled growth. He says this problem could be traced further back and concurred with Pineda that wells with a depth of up to 500 feet supply water to urban areas. “We are trying to obtain more water for the city,” he added.

Sara Dubón, regional director of ICF in Santa Rosa, reiterated that the city’s water sources are being depleted, and substantial forest cover is needed to replenish the aquifers. “It won’t be possible to live here anymore,” she said.

Sara explained that the Mayor’s Office has authorized the division of land suitable for forestry into large plots: “These are private properties, which we respect, but one has to be cautious and make sure that those projects are environmentally friendly.”

On January 2, 2024, local leaders organized a protest against the change of land use in a forest near Santa Rosa de Copán. They marched to the town hall with plants, placing them in front of the building and yelling multiple times: “We want to protect the environment in Santa Rosa!”

Days later, there was a demonstration in support of Mayor Alvarado, who claims to have been a victim of political persecution by his adversaries. He’s serving his fourth term as mayor of Santa Rosa.

Henríquez says it’s difficult to find a socio-environmental balance. “The objective is to collaborate not only with the Mayor’s Office but with ICF, the National Agrarian Institute, the military, and National Police. We are all responsible for what happens in the municipality,” he said and asked, “Why are we only blaming the mayor and the municipal council?”

In December 2023, the city launched a project called “Green Municipality” – whereby different civil society groups and the government have tackled environmental issues from different perspectives.

Sara Dubón proposed working collaboratively. She hopes that this initiative will give rise to a social movement in favor of environmental protection in Santa Rosa because as she argues, “it’s not fair that we are dependent on the whim of one person to decide what to do with the resources that communities will need in the future. We are very apathetic and don’t like people saying we are rebellious, but we have to act or else we won’t have a say in policy in Santa Rosa.”

Elvir explained that the municipal council has tried to issue three urbanization permits, one of which implies a change of land use in an area suitable for forestry. Mayor Alvarado owns one of the properties, which would be valued at 40 million lempiras (about $162,000) if the permit is issued.

Contracorriente contacted Mayor Erazo to understand his version of the events, but interview requests went unanswered.

According to the municipality’s transparency portal, 702 permits for the construction of houses and commercial buildings – both in old neighborhoods of Santa Rosa and areas adjacent to the forest – were issued between 2022 and 2023. The portal doesn’t show records of land divided into plots during this time.

Journalists and communicators are not the only ones under threat of violence for protecting natural resources in Santa Rosa de Copán. Ramiro Lara is an environmentalist and human rights defender whose house was shot at by unknown individuals on the evening of September 17, 2023. He told Contracorriente that the attack could be connected to his and others’ activism in defense of hectares of forest close to a water source called La Hondura – the same area where Jorge Posadas denounced illegal logging.

Ramiro Lara was forced to flee the city after the attack. Shortly before leaving, however, Ramiro told Jorge in an interview that a public official from the municipality asked him to stop reporting on the environment because he’s not familiar with the issue. Jorge says he has felt threatened since he started reporting on the environment, but he is more concerned about his safety after Lara’s house was shot 26 times. “This is a complicated matter. We get tired and feel we are on our own,” he said.

Journalists and communicators hope they will continue doing their job under better protective measures, and they are not backing down. Yalile says that despite such harsh consequences, she believes she has done the right thing: “I have defended the forests for future generations.”