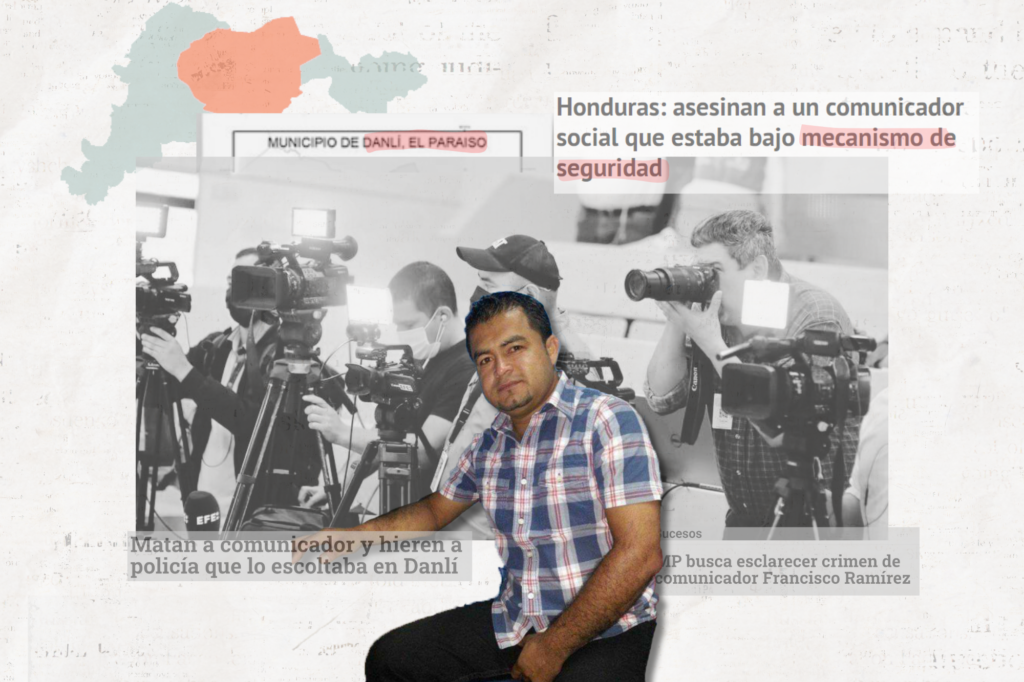

Journalist Francisco Ramírez was murdered in Danlí, department of El Paraíso, on December 21, 2023. He received protection measures from the Protection Mechanism for Human Rights Defenders and Journalists after a murder attempt in May of the same year. The United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights reported 145 cases of aggression and the killing of two journalists in 2023, and human rights activists are demanding policy changes to the protection mechanism.

Text: María Celeste Maradiaga

Photography: Jorge Cabrera and Fernando Destephen

Cover: Persy Cabrera

“In this country, being an activist or knowing sensitive information and releasing it is a crime and constitutes a death sentence,” said Xiomara Gaitán while conversing in a coffee shop in the city of Danlí, eastern Honduras.

Gaitán is a well-known activist in Danlí. She’s the president of the Network of Communities Affected by Mining in Honduras (Red de Comunidades Afectadas por la Minería en Honduras – Renacamih) and has assisted migrants in transit who stay in shelters. She also plays an important role in decision making in the municipality as she was part of the Municipal Council of Citizen Security in Danlí (Consejo Municipal de Seguridad Ciudadana) and stays abreast of issues and measures discussed there. She says she knows every resident in her hometown of Danlí, including average and prominent persons.

Francisco Ramírez was Gaitán’s friend and one of those prominent residents. Chico, as she remembers him, was a reporter on Channel 24 in Danlí and driver for the Attorney General’s Office. His murder shook the municipality, even though he had been attacked seven months before.

On May 3, 2023, Ramírez was shot three times and rushed to the Gabriela Alvarado Hospital in Danlí. After the attack, he received protective measures from the Protection Mechanism for Human Rights Defenders and Journalists in Honduras, including a police escort and a bulletproof vehicle, and was told to remain in Tegucigalpa, Honduras’ capital, until it was safe to return to Danlí.

However, Ramírez returned home in November, months after he stopped working as a journalist. As he was not receiving an income to provide for his family, he was forced to return home, which did not have any cameras and whose perimeter was not secured; such measures were not taken, depriving him of a safe place.

A month later, at Christmas time, Ramírez and his escort were heading home when they were attacked. He was shot five times and was instantly killed.

Germán Chirinos – environmental activist from Movimiento Ambientalista Social del Sur por la Vida (Mass Vida) and representative of civil society within the National Protection Council (Consejo del Sistema Nacional de Protección) – explained that the council doesn’t know the details of cases, particularly denunciations or the work carried out by Ramírez to determine if these had a connection to his murder.

“Considering how sensitive this issue is, and in order to maintain strict confidentiality, details of problems that journalists face are not disclosed to the Council,” Chirinos tells Contracorriente. Members of the National Protection System (Sistema Nacional de Protección – SNP), however, do know about these cases in detail.

One of the individuals suspected of murdering Francisco was arrested and held on pretrial detention on January 25 of this year. The Attorney General’s Office alleges the suspect has ties to Los Panteras, a criminal group “involved in several illegal activities” in this region in Honduras. In May 2023, two alleged members of this criminal group were accused of murdering Juan Carlos Vega, councilman in the Danlí municipality, in April 2022.

We spoke to Subcommissioner Aníbal Serrano Nieto in a meeting hall at Danlí’s police station. He says they knew what measures were needed to protect Ramírez and regrets that the police escort was wounded in the attack. Ramírez should have been more careful to avoid his death, he adds.

“It’s unfortunate that he went to a public place where alcohol is sold and conversed with people the day he was murdered, risking the life of the police escort. They were attacked while driving back to his house,” Serrano explained.

Ramírez covered many issues such as problems that dairy producers in the market are facing, local sanitary conditions, pothole patching, but also more sensitive issues within communities: murders, massacres, and confiscation of drugs – the kind of reporting that could make him a target for criminal groups, people close to him said.

To make up for the lack of a monthly salary and provide for his family, Ramírez also worked as a driver for the Attorney General’s Office. He faced financial hardships when he was sent to Tegucigalpa after the attack in May 2023 because he couldn’t do either of his two jobs.

According to the Law for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders, Journalists, Communicators, and Justice Operators – which was decreed in May 2015 and establishes the creation of the Technical Committee – the State, by the agency of the protection mechanism, should establish measures based on a risk analysis of each case and implement a monitoring and support system.

The Protection Mechanism has not made any progress either. Although Ramírez had filed complaints of bullying and harassment by employees of the Secretariat of Human Resources and the building was occupied in early February for 20 days, the committee has met only once this year, on March 21.

Furthermore, organizations like the Freedom of Expression Committee (C-Libre) have denounced that seven public officials from the current administration benefit from 85 percent of the budget allocated to the National Protection System, affecting many defenders or journalists like Ramírez, who, despite how vulnerable he was, did not receive all protective measures and support to seek asylum abroad.

Honduras’ general budget for 2023 allocated 143.8 billion lempiras (about $5.8 million) from the state treasury to the Secretariat of Human Rights (SEDH); of that amount, 3.39 million lempiras (about $137,811) were allocated to the protection mechanism in addition to 20 million lempiras (about $809,425) from the security tax fund (Tasa de Seguridad). According to a report by SEDH, the protection mechanism only implemented 40.96 percent of the budget.

The security tax fund is a trust which was terminated in May 2022, but the Honduran Private Enterprise Council (Consejo Hondureño de la Empresa Privada – COHEP), claims the government still manages the trust as shown by the protection mechanism.

In the report, SEDH also states that 153 human rights defenders, 15 journalists, 16 social communicators, and 18 justice operators – a total of 202 cases – were registered under the National Protection System in 2023.

“We are saddened because we had high expectations from this administration. I personally expected better guarantees for human rights defenders, but the greatest disappointment is that prosecutions, persecutions, and killings have increased,” Gaitán said.

She’s alluding to the impunity with which other communicators and journalists have been killed in Danlí. Juan Carlos Argeñal is one of them; he had denounced corruption in the healthcare system and was murdered in 2013.

C-Libre’s 2022 report on freedom of speech mentions the case of Jaime Nery Díaz, communicator and owner of Canal Aviva TV Danlí, who has faced administrative and legal actions since January 2022, when a reporter from his television channel denounced irregularities in the Danlí municipality, prompting the municipal council to shutdown the channel.

The reality of local reporters in Danlí

A local journalist in Danlí, who talked to us on the condition of anonymity, says there have been many changes in the municipality, especially for those who cover corruption and politics.

Migrants heading to the U.S. are charged triple the price of a regular bus ticket, exponentially boosting businesses in Danlí and bolstering money laundering and the drug trade. So, it’s challenging to work as a journalist because of the lack of support and resources to tackle dangerous situations. The latter has triggered rife practices such as bribery which is probably why important news are hard to diffuse, the journalist said.

Johny Rodríguez, director at Channel 24, described Francisco Ramírez as a very active journalist who would work under any weather conditions as long as he could report on what was happening.

“I had known Francisco for many years and we got along,” explains Noé, a colleague of his, while a pastor was preaching a sermon in the background in the morning show of Channel 24. He would send me six or seven reports depending on what was happening in eastern Honduras. We didn’t see each other often, but he visited communities and villages because he thought that’s where he’d find the news.”

Rodríguez says the channel has leveraged the coverage of news on social media and advertisements, which are run by journalists individually since not much revenue is generated from the news in Danlí, and media outlets have a bad reputation. As reporters, cameramen, and operators don’t receive a monthly salary, each one of them earns an income by running advertisements on the channel or social media.

Rodríguez told Contracorriente about an experience that left a mark on him: On July 15, 2023, when the Military Police was carrying out an inspection in the penitentiary in Danlí, he was beaten and threatened for filming a military officer who was shooting in the premises. They also took his phone. These events unleashed protests by relatives of the inmates.

By April 2024, the Special Prosecutor’s Office for Human Rights had not followed up on the complaint filed by Rodríguez over the assault in the penitentiary in Danlí. He asserted that his case and Ramírez’s prove how vulnerable local reporters, who have a more direct contact with communities, are.

Rodríguez said he talked to Ramírez one month before his murder. He was coming to Danlí to visit him, but said he couldn’t bring him anything from Tegucigalpa because he was struggling financially. But Johny told him that’s not important. One month later, Ramírez was murdered, and Rodríguez couldn’t believe what was happening.

Since then, he fears there will be repercussions for the denunciations and coverage by the media outlet. Chiefs of police, politicians and criminal groups have threatened him with violence if he doesn’t shut down the channel, but it was after Ramírez’s murder that acts of intimidation started increasing.

“After a colleague is murdered, one feels fear, and it’s hard to tell what kind of coverage and reporting is going to upset people because some of them don’t take criticism well. But here we are, being careful about the content we put out there,” Rodríguez concluded.

The struggle of community radio

On February 13 of this year, the Association of Community Media of Honduras (Asociación de Medios Comunitarios de Honduras – AMCH) held a press conference outside the National Congress, demanding participation in discussions on the creation of a special commission to analyze the situation of freedom of speech and community radio stations in Honduras.

During her visit to Honduras, Irene Khan, United Nations Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression and Opinion, pointed out the importance of addressing the needs of community radio stations, civil society and communicators, prompting the creation of the special commission. However, its reach in terms of overseeing media outlets, journalists and community radio stations is not clear.

“We think that local radio stations are the most vulnerable when it comes to freedom of speech. No law can be passed by Congress without an inclusive dialogue between the commission and the 70-plus existing local radio stations in Honduras,” stated Amada Ponce, executive director of C-Libre, during the press conference. Those who were present in the press conference then met with the National Congress’ Special Commission.

Jorge Andino – director of Play FM, a local radio station in northern Honduras – says it’s alarming that there are no guarantees to protect journalists and social communicators, especially because they are more vulnerable to threats and intimidation for covering news in their communities.

“Local radio stations lend a voice to communities who are besieged, robbed and forcefully displaced by extractive economies. These stations also listen to Indigenous communities whose languages – which should be protected and are important for cultural development – have not gone extinct yet. This puts us in a vulnerable position because when we tell stories from communities in an outspoken manner, we are up against the repression of those in power,” Andino said.

According to a report by Honduras’ National Human Rights Commission (CONADEH), its offshoot, the Internal Forced Displacement Unit, assisted 66 journalists threatened in relation to their reporting between 2021 and 2022.

CONADEH found that 97 journalists, commentators, photographers, editors, operators, and media owners were violently killed between 2001 and 2023, and 90 percent of these cases remain unpunished.