Honduras’ sugar industry employs about 200,000 workers during harvest season. Refineries have subcontracted most of the harvesting to individual workers, who are not protected by labor rights, such as social security or unemployment benefits. Payment is based on the amount of harvested sugar, and workers often earn less than the minimum wage. Those who want to earn higher wages have to push their bodies to the limit and work on weekends.

Text and photography: Amílcar Izaguirre

Juan Flores, 59, dropped out of school after a fight with his cousin and after being hit by a teacher when he was 12. He doesn’t recall what caused that conflict as a child. He has had many tough jobs ever since and now works as a harvester on a sugar plantation in the municipality of San Manuel, Cortés department, northern Honduras, where most of the sugar in the country is grown.

Looking for work and a better future, Juan left the municipality of San Francisco de Coray in the southern Valle department after Hurricane Mitch in 1998. He worked for many years on banana plantations in San Manuel, and has worked on sugar plantations for 14 years. It’s temporary work with no social security and an unfair wage since he is employed by a contractor that sells services to sugar refineries – of which there are four in Valle de Sula.

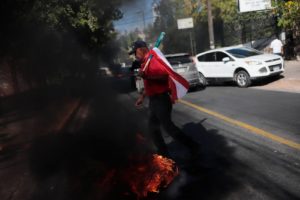

Harvesters are paid by the meter of sugarcane they cut. To avoid injuries, they use gloves like those used by goalkeepers in soccer matches. To make the harvest easier, avoid snake bites, and get rid of dry leaves and weeds, they burn the fields before cutting the sugarcane. During harvest, the cities of San Pedro Sula, La Lima, El Progreso, and Villanueva are covered with layers of smoke that pollute the air and restrict visibility. Locals have demanded in council meetings that they stop burning the fields.

According to Forbes Centro América magazine, Honduran sugar refineries directly and indirectly hired some 200,000 workers between 2019 and 2020. They produced 11.5 million quintales (a single quintal equals 100 lb) that season, of which 70 percent was destined for domestic consumption and 30 percent for exportation to international markets.

Oney Montes – the person overseeing the transportation of sugarcane for Compañía Azucarera Hondureña S. A. (CAHSA) – says 13 metric tons of sugar are processed every day on average. Moreover, 60 percent of sugarcane is harvested by hand and 40 percent mechanically, the latter technique is also known as “green harvest” because it doesn’t require burning the fields.

Montes, an expert in the industry with 23 years of experience at the company, says the goal is to harvest 100 percent of sugarcane mechanically, a practice he considers environmentally-friendly. “We’re taking small steps, but 40 percent is a significant amount and by next year we hope to harvest 50 percent by hand and 50 percent mechanically.”

According to Montes, a large investment is required to reach a fully mechanized harvest because machinery is expensive and fields have to be leveled in order for the harvester to operate. If a fully mechanized harvest system is in place, there would be less demand for harvesters.

“Pre-harvest field burning is practiced in many countries like the US and Mexico and in Central America too, of course,” he said.

The use of technology for harvest would be a problem for sugar refineries because there aren’t enough skilled workers in Honduras. To fill those jobs, refineries hire loader and harvester operators from Nicaragua, a country with skilled workforce. “They started harvesting sugar in Nicaragua before we did, and that’s why they have a more developed industry,” Montes said.

Harvest began on January 12 and is expected to end in mid-May, that’s four months of continuous work. When the season is over, companies hire few workers to sow, clean, irrigate, and fertilize sugarcane, while most have to wait till the next year.

“We even get cramps on our body for doing this kind of work,” Juan Flores said as he looked for a water bottle among the dry cane leaves. His face turned black after wiping the sweat off his forehead with his hands, which were covered in dirt and ashes.

Juan has harvested sugarcane for many years, but he could barely afford the plot of land where he lives. He has six sons, and two of them also work in the fields. “This is tough work. Workers are drenched in sweat,” said Juan while pointing to his sons, who were cutting cane. One could see the drops of sweat falling to the ground.

Young men who live near the sugar plantations prefer to work in sweatshops. There are few men who dare work in such extreme heat and harsh conditions. This is why the company subcontracts with workers from the south: they’re known for being the best at this kind of work and can withstand high temperatures.

José and Onny Ríos are cousins from Concepción de María, Choluteca, and harvesters for the same company. While José took a short break and sharpened his machete, he said, “Southerners are quite tough. My cousin and I have managed to harvest 1,200 meters, 600 each, but if you’re not used to harvesting that much and one day you pull it off, you’ll have to take the next day off because of exhaustion.”

José explained that with the money they earn in harvest season they buy fertilizer and herbicide to grow corn and other crops in his town because “it’s difficult to find a job there.” When harvest season is over, they go back to Santa María to work the land and grow corn, which is harvested in January or February. “If you don’t use fertilizer, the land won’t yield any crops, and last year the cost of one quintal of fertilizer was between 1,100 and 1,200 lempiras ($45 – $48). President Castro has increased the prices of all products,” he said.

A supplier of fertilizer said the price of a quintal of urea increased from 480-500 to 1000-1,200 lempiras in less than two years due to a container shortage in Asia, the surge in oil prices, and the war between Russia and Ukraine. Russia is the second largest exporter of fertilizer after China. The war led to a price increase of more than 100 percent. Those figures have been an excuse for dismissing complaints from producers in the agricultural industry.

On the sugar plantation I also met Wilmer Ramirez, a harvester from San Manuel, who explained that most workers don’t have a choice and have to endure the harsh conditions during harvest season. Many harvesters, however, are aware that they are not paid a fair wage. “In San Manuel, for example, a construction worker earns between 250 and 300 lempiras ($10 – $12) for a day of work from 6 a.m. to 4 p.m. We earn 70 cents for every meter of sugarcane we cut, and in order to earn 300 lempiras a day, we have to cut approximately 430 meters, but most of us don’t make it. Sometimes we earn 3,600 lempiras ($146) a week, but we have to work on Sundays, when we earn twice as much. Sometimes we work until 7 p.m. when a particular plot of land has to be finished and use lighting from the machinery.”

Another young man who was listening to the conversation, “Some of our coworkers earn good wages depending on how hard they work; some earn 6,000 lempiras a week, but others earn only 2,500 or 3,000 lempiras. At times, we put in a lot of work and only earn 200 lempiras a day because the sugarcane is tangled and little progress is made.”

Ríos says that refineries offer some benefits to workers that are not from the area. They offer workers accommodation at no cost and a subsidy for food expenses. A worker usually spends 800 lempiras on food each week, but the company pays 500 and they pay the rest. Honduran companies also hire harvesters from Nicaragua. They come to Honduras because they earn a higher wage here, and, while it’s not a fair wage, it’s worse in Nicaragua due to the lower minimum wage there, said Victor Zepeda, a Nicaraguan man and native of Nueva Chinandega who has worked four seasons in Honduras.

“We earn a bit more in Honduras, up to 7,000 lempiras for two weeks of work, while in Nicaragua we only earn 6,000 córdobas, and for 100 lempiras I get 130 or 140 córdobas in exchange,” Victor said. In Nicaragua, there’s a deduction for social security and it’s mandatory even for those who have informal jobs in agriculture, he explained. “If a worker earns 6,000 córdobas for two weeks of work, there’s a deduction of 500 córdobas for social security.”

At the side of the road, between the fields of sugarcane, three women are preparing food for workers. Today’s menu is chicken with plantain chips, beef, and pork at a price range from 60 to 100 lempiras. Rosalina Hernández owns the diner; she’s 58 years old and has been selling food in harvest season for 31 years. She cooks about 200 meals a day and barely manages to sleep two hours as she wakes up at 3 a.m. every day to prepare the food.

She hired two female workers from Choluteca seven years ago, Sandra Aguilera and Karen Castillo from the municipalities of Orocuina and Pespire, respectively. They’re the only employees who have worked for a long period of time at the diner.

“Southerners are the only ones who can endure the heat,” said Rosalina as she watched Karen fry plantain chips on a stove outside the tent and the midday sun shone from above.

A first-aid station stands about 100 meters from the diner. Here, Martha Ruth Gonzales Ayala, a nurse employed by CAHSA, performs her duties. She tends to no less than 400 people, including harvesters, water carriers, and contractors. Martha says she has had to help workers regain their consciousness after they faint due to the high temperature or physical exhaustion from cutting sugarcane. She gives them water and a saline solution to avoid dehydration and patches them up when they need stitches, usually on a daily basis.

Martha is a single mother of two boys, a high school student and an elementary student. She lives in the community of Guacamaya between El Progreso and Santa Rita. She has to wake up at 4 a.m. and take the bus with other workers who travel from Santa Rita to San Manuel to be on time at work. She works under a tent where she sets up her kit which contains different kinds of medication, pills for headaches, dizziness, and other supplies to tend workers’ wounds.

A group of harvesters covered in ashes who had just burned the fields were waiting in line in front of a yellow cylindrical fridge. Martha handed out a saline solution, red with fruit flavor, evenly to the thirsty workers. The workers drank approximately 450 ml of the solution in improvised plastic cups made from soda bottles. “It’s not enough, but it makes them feel a little bit better,” said Martha. She prepares two bottles of saline solution every day, but most of the time it’s not enough.

“We started handing out a saline solution this year, but it’s a trial, and if we get the results the company is looking for, it’s going to be permanently available for the coming harvest seasons,” she said.