Text: Teddy Baca

Graphic: Daniel Fonseca

Translated & Edited by: Jorge Paz Reyes

Many things have happened since I last wrote for Contracorriente: I finished some diploma courses, I started writing a new book -which I later canceled-, I found a job, I ended and started working relationship, among other things.

Currently, I find myself recovering from one of my depressive episodes, in an emotional journey that is neither easy nor fast. And even less in the back and forth of memories that emerge within me as I try to understand how I came to develop a depression disorder (which to this day continues to take its toll on me from time to time).

Religion is one of the three triggers I have identified, and although I have written about its impacts, I believe I still need to write about my personal experience.

Childhood

I believe the majority of children in Honduras have been indoctrinated into Christianity from a very early age; proof of this is the attendance of Sunday school, baptisms, punishments based on “disobedience” to the Bible and the socialization of the Bible to the point of being considered an unquestionable truth.

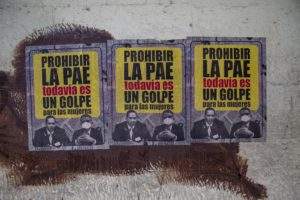

Even in public schools there has been an attempt to impose religious reading to minors through a bill introduced by the ultraconservative administration of former president Juan Orlando Hernández; and in the National Congress through Mauricio Oliva, Tomás Zambrano, David Chávez and their alliances with evangelical organizations.

When I attended Sunday school as a kid, I was conditioned to see the Bible as the absolute truth through games, candy events and reading contests.

But the apparent joy would not last long: at the age of 8 years old, my sexual attraction emerged, which was not towards women, but towards men. Previously, I had heard negative and insulting comments about homosexuality from Catholics and Evangelicals, but it was not until I read a text from a Baptist Church that a chronic emotional pain began to take shape inside me.

The text read – relying on my long-term memory – “Decriminalizing homosexuality is a sin, the state should not allow it”, among other equally regrettable phrases.

That day was the first time I cried about the fear of going to hell, I sought comfort in texts from different churches, including Jehovah’s Witnesses, Baptists, Apostolic and Catholics, but none helped me, all worsened my crisis as if it were a snowball falling from a cliff and increasing its mass until it became potentially crushing.

Some phrases were repeated, with some variations according to each dogmatic approach:

“Homosexuality is eternal death, it is aberration,” I read.

“Homosexuals must change and repent,” I read.

“They will not inherit paradise,” I read

And I suffered each time, more and more, without finding a message that was different. In my childish mind, I tried to avoid thinking or talking abut the subject, even though I started liking a school mate.

I would cry at night asking God to “change me,” while occasionally the country’s media outlet would broadcast homophobic headlines and “news” that only fueled my painful journey through sexuality.

On television, there were evangelical programs that claimed to have “recovered people from homosexuality”, as if it were a kind of disease, when it is not. Every day I saw self-styled “ex-gay” people whose facial expression said the opposite from what their churches would tell them to say. Years later I realized that no one can stop being LGTBIQ+, and confirmed it with scientific research.

I spent 8 years in denial and suffering. My parents, who were not ill-intended but ignorant about homosexuality, were sympathetic to evangelical churches and shared many of their beliefs, so I could not tell them how I felt.

It was my first secret, and the one that marked me for life.

Teenage years

They say you can run away from everyone but yourself. There are many LGTBIQ+ people who live a double life to hide themselves. That was my story for a few years, until finally something pushed me out of the closet, a captivating and intense force: romantic love.

I fell in love for the first time at the age of 16. With a man, obviously. When I was in high school, he was in another class. Thanks to my feelings for him, I had the courage to come out to my friends.

That was also when I began to question Christianity for the first time. I realized that not only on issues of homosexuality the Bible and the Church were going the wrong way, but also on the origin of the earth, of the human being and on different aspects of women’s rights.

However, I did not consider myself an atheist, I had some remnants of all that accumulated dogma. My experiences with dissident Mormons, some Methodists and Anglicans, made me think that maybe it was not the religion that had a problem with homosexuality, but many of its leaders who disguise their hatred with faith, but as I investigated further, I realized that there really is an association between the religion and anti-gay prejudice.

I did a lot of research on the psychology of sexual diversity, on anti-LGTBIQ religious organizations like Hazte Oír, Focus on The Family, Exodus and WatchTower, and I came to a conclusion: if I wanted to have peace with my sexuality in my life, I had to abandon Christianity altogether.

And I was not wrong, to date I have not had any sexual complex since then, although I admit that it is not necessary for all people. Reconciling faith with sexuality is possible if the belief system does not condemn sexual diversity.

But despite this, depression was already settled in. With each crisis, each blow to my self-esteem, my depressive disorder fully developed by the age of 18.

Adult Life (present)

Little by little I came out to more people; while that was happening, I was living my first year of college. Before I turned 18, I confronted all my internal prejudices with the help of books and scientific papers. It was hard to confront the mental schemes already internalized in me but I committed myself to question everything.

While in the process of fully discovering myself, my first university friendships seemed to provide me a safe space to keep my self-esteem intact. Until a former friend, a staunch Baptist, told me: “I don’t know why people cry for relatives that like that (queer) and pray for them, they are going to hell and that’s it.” That destroyed me in three seconds.

That day I went to cry to another friend, and that marked the beginning of the clinical problem.

In the Department of Psychology, you would think I would find a safe place to be who I was and am, but I didn’t. I spent over two years immersed in an emotional problem exacerbated by my time there.

They were years of professors, generally related to religious fundamentalism, and student supporters of Agustín Laje or similar, engaging in homophobic and transphobic rhetoric.

It also didn’t help much that the Department of Psychological Sciences was full of religious people deciding what was “ethical” or not, or making passive-aggressive comments against homosexual affection.

At the time, I was going through stressful experiences unrelated to my sexuality but the messages of the traditional media worsened my condition. The hate speeches against sexual diversity, defending religious people with the excuse of freedom of worship, as the cases of Evelio Reyes and Marlen Alvarenga further contributed to my depression. The first one stigmatizes us with the absurd phrase “enemies of God’s models” and the second one cataloged us as “aberrations”, both discourses that curiously manifested prior to elections.

The justice system did not sanction them and even justified them with “biblical truth”, as if human rights did not matter or the secular state was not recognized. Inside me there was a clear message being sent to us by the decision makers: “This country hates us”.

There is no such thing as “love the sinner, not the sin”, my homosexuality is part of me, no one should or can separate it. We were definitely hated to the point that every death of a fellow queer person at the hands of hate meant additional pain for us and no pain for those who ruled at the time.

In the present not much has changed, there are still people with fatal comments and acts against sexual diversity. Religious fundamentalist figures such as Evelio Reyes, Roy Santos, Alberto Solórzano, among others, who continue to issue harmful comments against LGTBIQ+ people with total impunity. There continues to be religious interference in the State’s attempts to recognize our rights; media that lend themselves to stigmatization and orchestrate a media war against our demands and struggles, as happened in July 2022 in collusion with the Pastors Association of Tegucigalpa, who even organized a protest where they “invited” us to convert. To know the serious implications of promoting “conversion” I invite you to read my article on “Ecosig en Honduras.“

But among all this pseudo cultural fecal matter and false morals, I found three exceptions that make me think that the Christian religion can genuinely respect sexual diversity.

Father “Melo” and his work with the Jesuit Church, for example, who have supported formative processes in favor of human rights and sexual diversity.

The Ecumenical Advocates for the Right to Decide, who have been in favor of our demands and advocating for a theology respectful of LGTBIQ+ dignity.

And, finally, those independent churches that, with efforts, try to implement a liberation theology, where our rights, including equal marriage, are valid and necessary to consider us citizens of equal status as cisgender heterosexuals.

These are not spaces exempt from criticism, but they are definitely lessons that I believe other religious organizations need to learn.

Personally, I will never go back to Christianity. I believe that the wounds I have are a gentle reminder that the first sign of self-love is self-acceptance. I accept myself as I am: I was never straight, I have always been LGTBIQ+ and I always will be. Regarding my parents, the situation on the subject has improved, especially my relationship with my mother, something which I thank the God that I believe in. Because I do believe in one, one of love.

Today, I have an emotional relapse, but I believe I can come out of it with better results than before, because one of my main stressors no longer has that power over me.

I took away the power from that religious rhetoric that I’ve lived with for almost all my life.

I wish peace and love to all LGTBIQ+ people: we need it.