According to official data, Tropical Storms Eta and Iota caused the death of 96 people. One devastated family speaks out about the government’s unreliable death tally, demonstrating that the true number of deaths is unknown.

By Fernando Silva

Photos by Deiby Yánes

It was after dark on November 4 when the Sabillón family heard the sound of water overflowing from the ravine behind their house. The water flowed into the street as they began to take videos with their cell phones. They heard the rushing waters of the Cececapa River right before it swept them, and the trees and walls that lined the neighborhood, away.

The Sabillón family lived in the village of San José de Oriente in northwestern Honduras (Ilama Municipality, Department of Santa Bárbara). Tropical Storm Eta hit this area hard, causing the flooding that swept away 30-year-old Argenis Sabillón, his father Oscar, his sister Andrea, his daughters Daphne and Sharon, his sister-in-law Maritza, and his month-old nephew, Didier.

As morning broke the next day, the community began a desperate search among the debris for the Sabillón family. They found Argenis still clinging to life and carried him to the nearest clinic. He succumbed to his injuries 10 days later at Mario Catarino Rivas Hospital in San Pedro Sula. The community searched for the other family members for over a week, eventually finding all of their decomposed bodies.

The government emergency management agency (The Permanent Contingencies Commission – COPECO) only recorded the deaths of four members of the Sabillón family, leaving the fates of Argenis, Daphne and Oscar in limbo. Not long after Tropical Storms Iota and Eta devastated the country, government authorities ended the official tally of the storm victims. This was a marked departure from international standards established by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which recommend that storm after-effects should be assessed until the full impact has been recorded.

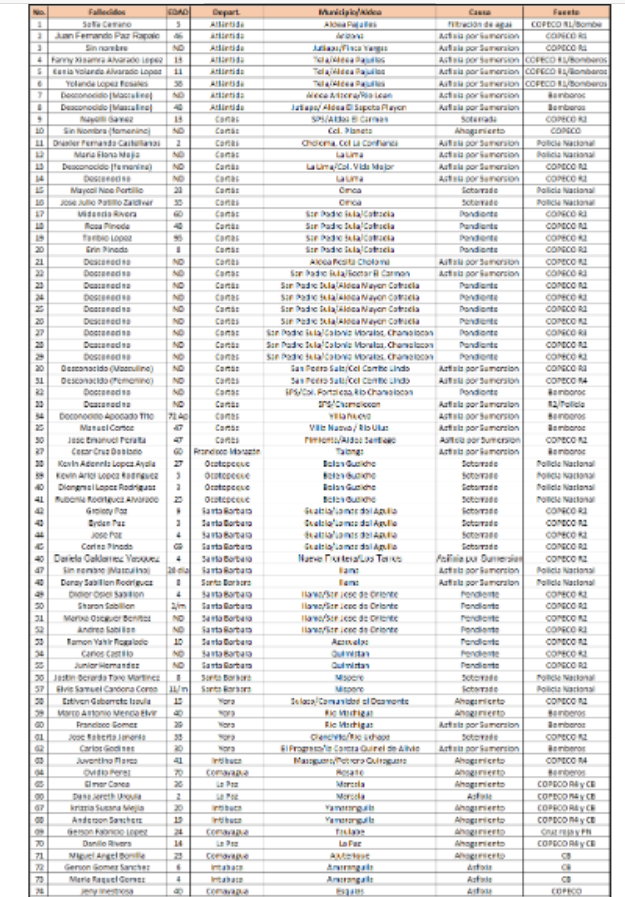

Contracorriente requested COPECO’s official records of the number of deaths caused by the two storms, which had their greatest impacts on the departments of Cortés, Santa Bárbara, Colón and Yoro. A COPECO communications official eventually produced a blurry list of 74 deaths caused by Eta, the most damaging of the two storms.

COPECO recorded 96 deaths caused by Tropical Storms Eta and Iota. However, experts say there is widespread underreporting because the government lacks the necessary data collection capability.

Dr. Fidel Barahona, a public health specialist, says that Honduras has no plan for ongoing surveillance of people with chronic health problems or to record the health status of storm victims. This is due to the disorganization of, and lack of experts in the institutions responsible for this function.

“By now we should have a report of the number of displaced people, the number of deaths, and the different types of diseases suffered by storm victims. All that information should be readily available if you have a well-designed epidemiological surveillance plan,” says Barahona, who proceeded to compare Honduras with other countries that do have these plans.

After Hurricane Florence hit North Carolina in September 2018, the Associated Press published an article citing experts who said, “It’s normal for fatalities from natural disasters to increase in the subsequent weeks and months, as many deaths are indirectly caused by those disasters.”

The article cites the example of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, where an initial figure of 64 deaths only included people whose death certificates reference the storm. However, the outcry by thousands of families who lost loved ones in the aftermath of the storm compelled the U.S. government to contract George Washington University to conduct a study that reported a final tally of 2,975 deaths – a number corroborated by other similar studies.

Citing this article, Dr. Barahona said “Many people die from infections caused by contaminated water, are electrocuted by downed power lines, or die because they couldn’t get dialysis treatments due to power outages. Deaths directly caused by storms include drowning victims and people crushed by collapsing buildings.”

“Furthermore,” said Dr. Barahona, “if deaths directly caused by storms are underreported, we can expect even less reliable data on indirect deaths, such as heart attacks caused by the extreme stress suffered by flood victims who return home and realize that everything they have worked on for years has disappeared and they are now condemned to complete misery.” A clear example of this is Argenis, who died in a San Pedro Sula hospital 10 days after being rescued.

Mirna Rosales, a cousin of Argenis, sent us a message with photos of the tragedy that showed uninhabitable, mud-filled villages, clogged by tree limbs and huge stones. It included photos of the seven family members who died in the Eta floods that destroyed the flimsy houses of the village. The most heart-wrenching photo shows a blue tarpaulin with the bodies of the baby and one of the young girls, who were found after a three-day search.

When Argenis’ neighbors found him unconscious and with seriously injured legs, they fashioned a stretcher out of a hammock to carry him to the hospital. Since the roads were impassable, they carried him 17 kilometers to a private clinic in the village of Peña Blanca, Cortés. He was taken from there to the hospital in Santa Barbara, and was transferred on November 16 to Mario Catarino Rivas Hospital, the main emergency care facility in northern Honduras.

According to Mirna, the doctors found that his leg wounds were severely infected, and he had gastrointestinal bleeding due to swallowing contaminated flood waters. He eventually died on November 16, but his body couldn’t be moved from the Justice Ministry morgue until four days later since he had lost his identification papers. This only added to the anguish of family members waiting to bury their dead.

Even though his fatal injuries were clearly caused by the storm and he died shortly thereafter, Argenis does not appear in the official records of victims maintained by COPECO, by the Ministry of Justice’s forensic medicine unit, or by the Mario Catarino Rivas Hospital.

According to Armando Ramírez, president of the special commission (Comisión Interventora) appointed to manage Mario Catarino Rivas Hospital, the hospital treated patients rescued from rooftops after the Ulua River flooded, but he told Contracorriente “We only treated them for dehydration. We didn’t have any immediate fatalities after admitting storm victims to the hospital.”

Ramírez admits that they are unable to collect comprehensive data on deaths in northern Honduras, and that some deaths attributable to the storms are not counted when people die in their own homes. “Someone can die from a heart attack or stroke when they are cleaning up their homes after a storm. But because they die in the communities and neighborhoods, this information isn’t reported to the hospitals. That’s a job for forensic medicine,” said Ramírez.

Dr. Vladimir Núñez, regional forensic medicine coordinator in San Pedro Sula, also acknowledged that they don’t keep records of deaths indirectly caused by disasters, and that doing so would require a thorough examination of the available records.

An article in Criterio.hn reported on November 18 that Ramón Cruz, a Choloma municipal commissioner who collaborates with the Municipal Emergency Committee (Comité de Emergencia Municipal – CODEM), said that many bodies still had not been recovered, and that justice ministry officials had only provided him with some equipment so he could recover the bodies himself.

Requesting funds without any accountability

“I invite you to come to Honduras and see the destruction of infrastructure, bridges, homes, schools, hospitals and crops left behind by these two hurricanes with your own eyes,” said President Juan Orlando Hernandez last December in his speech at the Climate Ambition Summit 2020. However, the Honduran president’s invitation is supported by questionable data on both deaths and missing persons.

As unrelenting rains from Eta and Iota fell from November 5 to 19, Facebook groups sprung up to locate people stranded on rooftops. Social network posts named hundreds of missing people, but the government ended up reporting that only six to nine people were still missing.

The Honduran government has requested an advance of $35 million from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) to address the impacts of Tropical Storms Eta and Iota. However, the government does not maintain the reliable records of victims and missing persons needed to fully understand the impacts of these storms.

“There is no official list of missing persons, which is why it’s difficult [for the government] to say that it keeps records of all those deaths. The system is definitely not designed for that – it’s their lowest priority,” says Dr. Barahona.

The government’s top priority appears to be obtaining international funding to begin reconstruction work in the most heavily affected areas, but there is no evidence of an effort to quantify the human impact or respond to the needs of storm victims. Gustavo Boquín, a member of the special commission appointed to manage the government’s strategic investment agency, Invest-h, (Inversión Estratégica de Honduras) estimates that Honduras will need to invest 10 to 12 billion lempiras (US$410 million) in post-storm reconstruction.

Hernandez made sure to remind leaders attending the Climate Ambition Summit 2020 that “Honduras is a victim of climate change caused by industrialized countries. Therefore, access to climate change funds is a right – it’s not charity.” These were the words of a president who, in an effort to revive the economy, urged the public to travel and enjoy the annual Morazan holidays two days before the first storm hit the country.

The storm’s other impact

“It’s a tragedy – everyone has different needs. My mother was so traumatized that she had a heart attack. The doctors are going to evaluate her in January about inserting a pacemaker,” said Mirna Rosales. Two days later, she sent us another message about the death of Brenda Sabillón, a cousin of Argenis, who was diagnosed with cancer a few years ago. Brenda survived her cancer, but suffered a hemorrhage shortly after the storm and died on December 18.

Mirna told me about that tragic night for her family when only two of the nine people living in the house survived – Argenis’ brother, Milton, and their mother, Isabel Mendez. “Isabel lost her husband, children, grandchildren, home, and business. She also suffered hearing loss and is being treated by a psychologist.”

Marta Jiménez, a doctor with Doctors Without Borders in Choloma, said in an interview with Contracorriente, “I consider this post-hurricane situation to be a humanitarian crisis for several reasons. First, the public has no safe access to their homes or any other safe housing. Homes in many communities are still flooded, and even where the water has receded, the homes are full of mud. Families don’t have a safe place to live.”

Jiménez says the health ministry estimates that over 250,000 people currently have limited or no access to health services because of the country’s damaged infrastructure. After Hurricane Mitch in 1998, 123 health centers were severely damaged, affecting nearly 100,000 people. Many people displaced by Hurricane Mitch moved to vulnerable areas that were once again heavily affected by the recent storms.

According to Doctors Without Borders, other risk factors to consider are mental health needs. “The post-hurricane period is precisely when mental health needs rise sharply, as people struggle with the stress, anxiety and grief of losing material possessions, family members, other loved ones, and even the loss of animals,” said Jiménez.

Dr. Julissa Villanueva, former director of the forensic medicine department of the Attorney General’s office, says that disaster-related deaths will continue to quietly increase for these very reasons.

“The epidemiological surveillance of diseases and deaths related to natural disasters is not part of the government’s reporting effort. Neither the Ministry of Public Health nor COPECO have expressed any interest in this, and the Ministry of Human Rights should be tasked with investigating why not,” said Villanueva, adding that anyone looking at the official data will quickly realize that Honduras has always underreported this type of information, which ultimately obscures the reality of the situation.

Dr. Villanueva explained that national and international guidelines for handling dead bodies during natural disasters require that the authorities identify the bodies and return them to their families with an explanation of the cause of death. But it was the people of San José de Oriente who took it upon themselves to recover and identify the bodies. Mirna Rosales noted that Agustín Muñoz, mayor of Ilama, never showed up to offer help.

“Underreporting affects us because we don’t know if Honduran society is being adequately protected by effective public health policies. How many hundreds of people died from the hurricanes? These people deserve to be properly buried. But nobody is interested in determining the true numbers. This information will soon disappear for good and everyone will eventually forget all about it,” says Dr. Villanueva.