President Castro’s decision to denounce the US-Honduras extradition treaty is not a response to “US intervention through its embassy,” but a way of protecting political allies with ties to organized crime, says Fátima Mena, lawyer and congressional member of the Salvador de Honduras Party.

Text: María Celeste Maradiaga

Photography: CC Archive

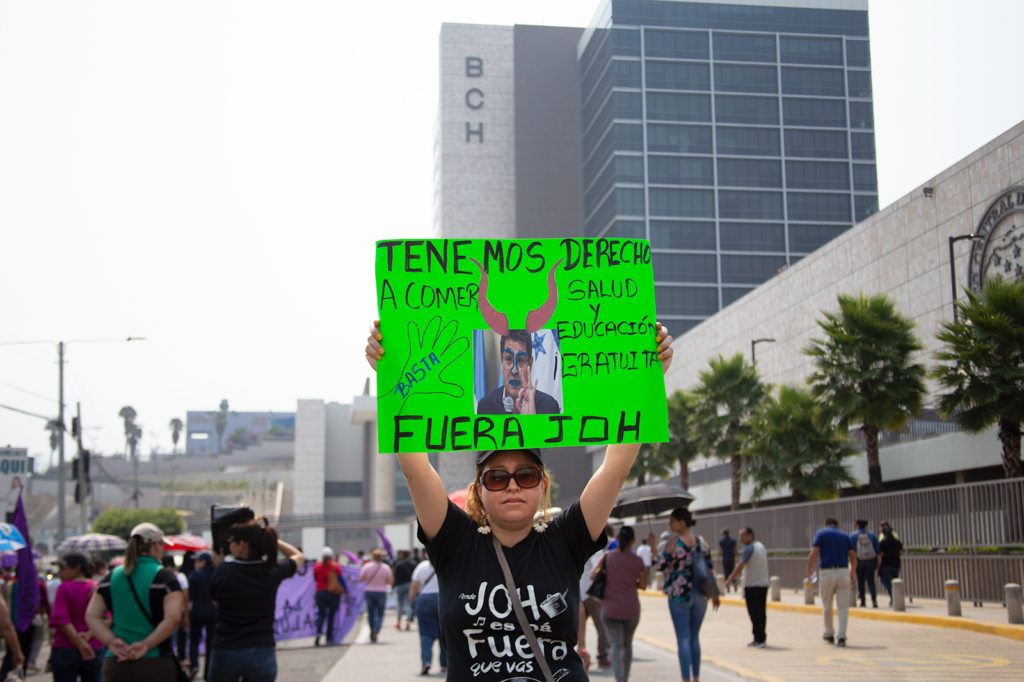

On August 28, President Castro ordered Foreign Minister Enrique Reina to denounce the US-Honduras extradition treaty as “interventionism from Washington” in the country’s affairs.

The announcement was made via X in response to statements by the US Ambassador to Honduras Laura Dogu criticizing a meeting between the Honduran and Venezuelan Defense Ministers, José Manuel Zelaya and Vladimir Padrino. Dogu said she was surprised to see members of the Castro government meeting with “drug traffickers.”

José Manuel Zelaya is the son of Carlos Zelaya, secretary of the Honduran National Assembly, and nephew of President Castro.

Reina, who did not respond to interview requests by Contracorriente, told media outlets that the treaty had not been terminated yet and the denunciation, for which there is a provision in the treaty, has to be followed through.

“I think there is nothing wrong with having dignity. Mutual respect is the basis for bilateral relations. This decision was made by the president and ought to be supported [. . .]. During meetings with officials in the US, we have made it clear that relations should not be strained by the ambassador’s opinions,” Reina told media outlets. He later posted a letter addressed to the US government via X, announcing Honduras’ withdrawal from the extradition treaty, in accordance with Articles 1, 15, and 245 of the Constitution.

Presidenta @XiomaraCastroZ he procedido a cumplir su orden de inmediato, remitiendo la Nota No. 111-DGAJTC-2024 mediante la cual comunicamos oficialmente la denuncia al Gobierno de los EEUU del tratado de extradición entre Honduras y EEUU. pic.twitter.com/aNhT9RduT3

— Enrique Reina (@EnriqueReinaHN) August 28, 2024

Article 14 of the extradition treaty stipulates that any signatory may withdraw from the agreement, provided the other signatory is informed six months in advance.

According to Mena, Castro’s decision is not a response to interventionism from the US in domestic affairs, as she and several officials have stated, but rather a way of protecting Libre Party’s allies.

“It seems to me that this decision had already been contemplated to protect members of the ruling party who have ties with organized crime. The president’s decision has nothing to do with statements by the ambassador. This is an assault on the justice that Hondurans have had, thanks to the extradition treaty,” Mena said.

She stressed that the treaty made it possible for Honduran authorities to extradite former President Juan Orlando Hernández and former Chief of Police Juan Carlos “El Tigre” Bonilla, both of whom were tried and sentenced in the US over drug trafficking charges. In addition, high-ranking officials with political and economic power have also faced justice. That degree of accountability has not taken place in Honduras.

The extradition of Hondurans to the US began after a supplement was added to an article of the Constitution that allows the extradition of Honduran nationals charged with drug trafficking, terrorism, and organized crime, and which invokes the US-Honduras extradition treaty of 1912.

The first drug-related extradition order was issued in 2014, when the US District Court for the Southern District of Florida indicted Carlos Arnaldo Lobo “El Negro” Lobo. Since then, at least 40 Hondurans have been extradited for their involvement in drug trafficking, migrant smuggling, and money laundering.

On September 4, Mario Cálix, a.k.a. “Cubeta,” will be the next Honduran to be extradited to the US. He is among the list of 16 extraditable persons issued by the Secretariat of Security, which includes Henry Fernández of the Valle Cartel, Juan Carlos Montes Bobadilla, and Alexander “El Porkys” Mendoza, leader of the MS-13 gang in Honduras.

Recommended reading: The Valle Cartel: a criminal organization that returned to Honduras, where they are untouchable

Extradition treaty must be repealed by means of a constitutional reform in the National Assembly

Raul Pineda Alvarado, constitutional lawyer and political analyst, says that in order for the US-Honduras extradition treaty to be terminated, Article 102 of the Constitution has to be amended. The article stipulates that no Honduran national may be exiled or handed over to foreign authorities, except in cases involving drug trafficking, terrorism, and organized crime if a treaty or agreement exists with the country issuing the petition.

Pineda recalls that access to the press was restricted during the legislative session that saw the approval of the constitutional reform. At that time, Juan Orlando Hernández was president of the National Assembly.

“Only the National Assembly is allowed to make constitutional amendments, and the article has to be amended before the State decides not to extradite Honduran nationals. The president’s denunciation does not suffice because she doesn’t have the authority to amend the Constitution,” Pineda said. A majority vote, 86, is needed and the reform must be approved in two legislative sessions.

Extradition law: A step backwards in the fight against organized crime

Regarding the possibility of discussing the Extradition Law in the National Assembly, Mena says this would not be effective since this project would obstruct the swiftness with which Hondurans have been extradited to the US, thanks to the resolution approved in June 2013.

“We knew that some factions of Libre would obstruct extraditions, but it is inconceivable and dangerous that in a country where the political system protects drug and crime lords, the government denounces a treaty that has been so effective in bringing them to justice. A withdrawal from the treaty would grant impunity to people who have not faced justice in the country,” Mena said.

In February of 2023, following the appointment of the Supreme Court magistrates, Rebeca Raquel Obando said during a press conference that it is possible to regulate extradition in Honduras. This renewed the debate about the Extradition Law, which had been shelved since March of that year.

However, the special commission in charge of this project has not made pronouncements or progress in the discussion of this law.

After signing oil agreements with officials and President Nicolas Maduro in Venezuela, Manuel Zelaya Rosales, former Honduran President and current presidential advisor, stated that no branch of government may end the extradition treaty.

“It is not possible to end the extradition treaty,” Zelaya Rosales repeated three times. “And there is no intention to obstruct that process. What media outlets are saying is just blah, blah, blah.”

El expresidente @manuelzr, aclaró que el gobierno de la presidenta @XiomaraCastroZ no tiene ninguna intención de cancelar, retrasar, obstaculizar o entorpecer el tratado y los procesos de extradición. pic.twitter.com/WM2opXzGMB

— Secretaría de Prensa de Honduras (@gobprensaHN) March 7, 2023