Eighteen deals have been registered in the name of Indigenous Carbon, a new company with ties to U.S. entrepreneur Michael Greene, who has been accused of public land theft by the Pará Public Defender’s Office

By Claudia Antunes (Sumaúma)

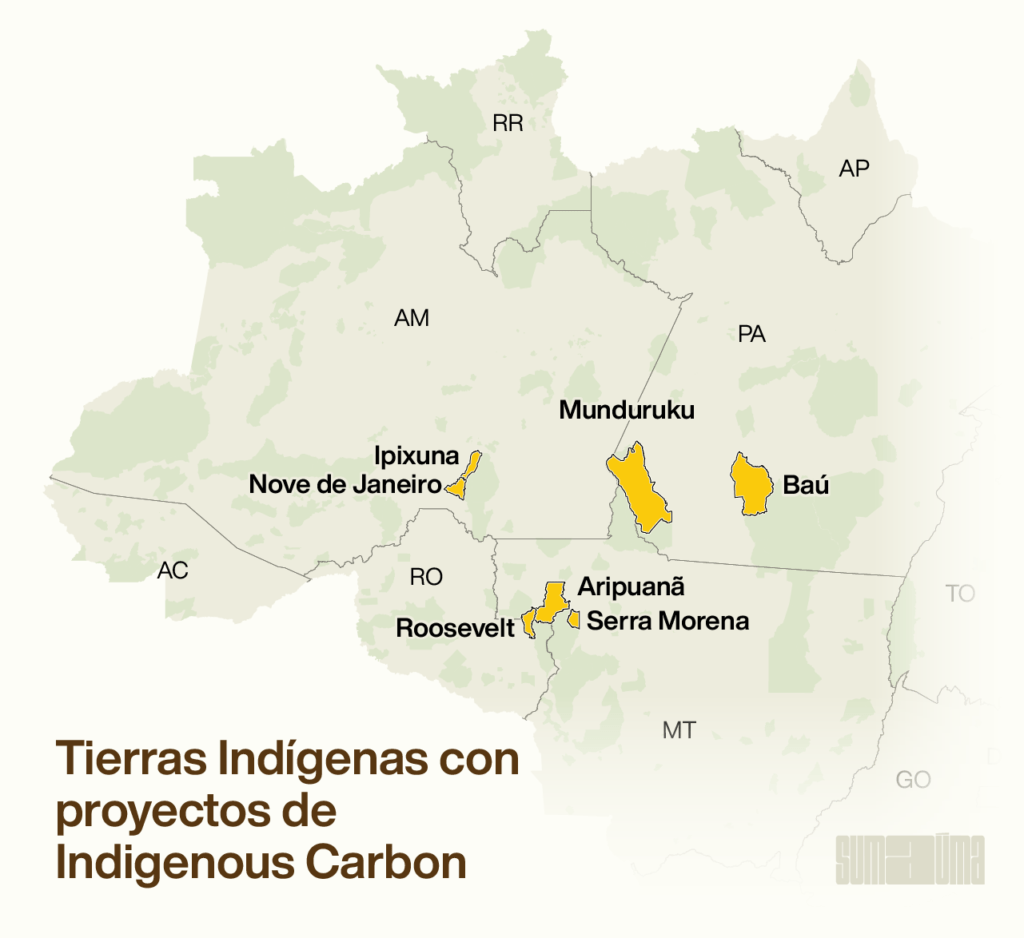

U.S. entrepreneur Michael Greene, who has been charged by the Pará State Public Defender’s Office with land grabbing related to carbon deals in the municipality of Portel, is behind 18 carbon credit projects registered by a company called Indigenous Carbon, in conjunction with Indigenous territory associations in the Brazilian Amazon. The projects involve the territories of the Parintintin Indigenous people in Amazonas state; the Cinta Larga in Rondônia and Mato Grosso; and the Munduruku and Kayapó, both in Pará. Except for the lands of the Parintintin, the territories that are the subject of Indigenous Carbon’s initiatives have been suffering from the invasion of illegal gold mining operations, which has sparked tension and division in the communities.

Based on interviews with people involved in project negotiations and records of an administrative process opened in Rondônia and a civil inquiry opened in Pará, both by the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, questions have been raised in these territories about the destination of the funds transferred by Greene for project implementation. Among other problems, this money includes the payment of salaries to Indigenous people, something that is intensifying disputes over the amount involved. There are also indications that protocols established by the Indigenous peoples themselves were not followed during contract consultations with them and that the associations did not have independent legal advice, although the latter is not a legal requirement. Additionally, according to a former project manager in the Munduruku Indigenous Territory, there were disagreements over the price Greene set for himself to buy and then resell the credits generated by one of the projects in the territory.

The Indigenous leaders who defend the contracts argue that raising funds through the sale of carbon credits is a way of protecting their territories from deforestation and putting an end to illegal activities, including gold mining and timber smuggling. However, at a time when the carbon market is under scrutiny, Greene’s participation raises doubts as to whether these projects will actually be able to sell enough credits to generate the hundreds of thousands of dollars in income expected by the Indigenous peoples.

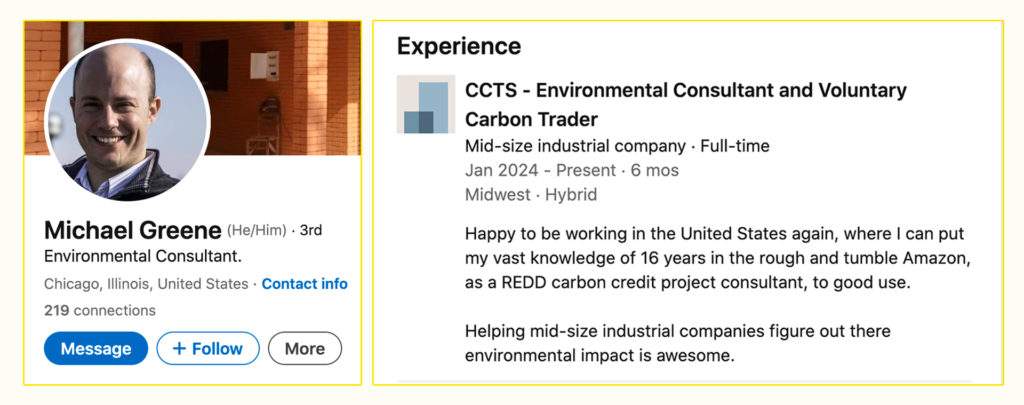

Michael Greene calls himself an “environmental consultant” and carbon credit trader. Married to a Brazilian, Evelise da Cruz Pires Greene, he claims to have lived in Brazil for 14 years. Greene appears as a partner in at least ten companies in the states of São Paulo, Minas Gerais, and Pará, with activities ranging from forest conservation to real estate. The first of these was opened in 2008. On LinkedIn, he says he has been working since January in the United States, where he hopes to use the knowledge he has accumulated as a carbon credit project consultant in the “rough and tumble Amazon.”

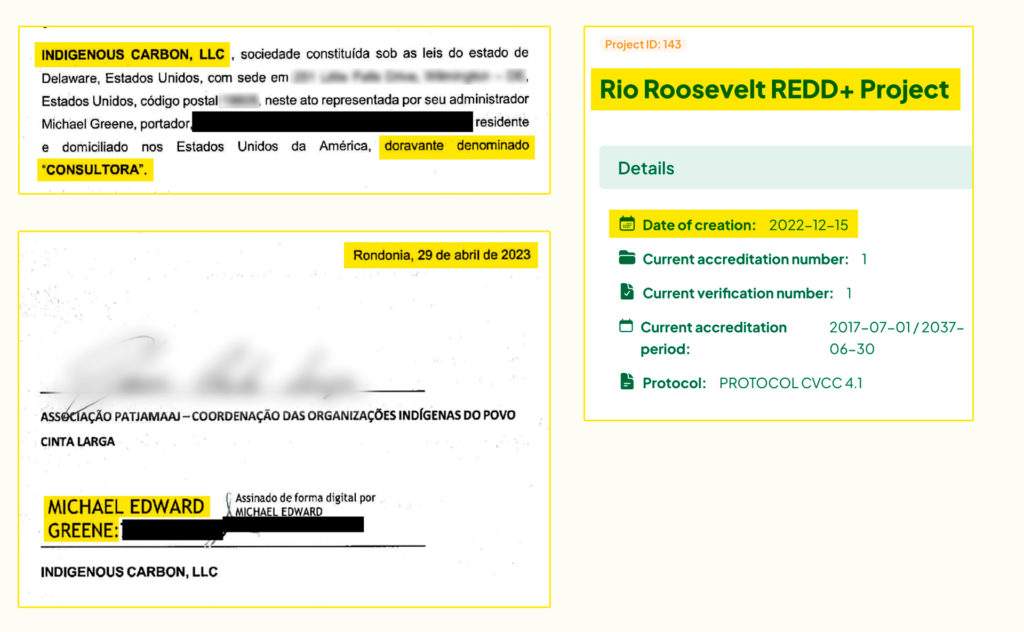

Indigenous Carbon was registered in July 2022 in Delaware, a U.S. state considered something of a tax haven because of its low level of financial transparency: it is possible, for example, to open a company there without revealing its owners. In late 2022 and early 2023, requests were filed for certification of the projects involving the Indigenous associations, a process that in theory should prove the credits are legitimate, in other words, that they actually represent a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, the main culprit behind global heating.

The four suspended projects in Portel had been submitted for certification to the U.S. organization Verra, one of the largest in the field. The Indigenous Carbon projects were registered with the Colombian firm Cercarbono, a lesser-known certifier that has yet to earn a seal from the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market, or ICVCM, a body that defines itself as independent and aims to raise quality standards in this market.

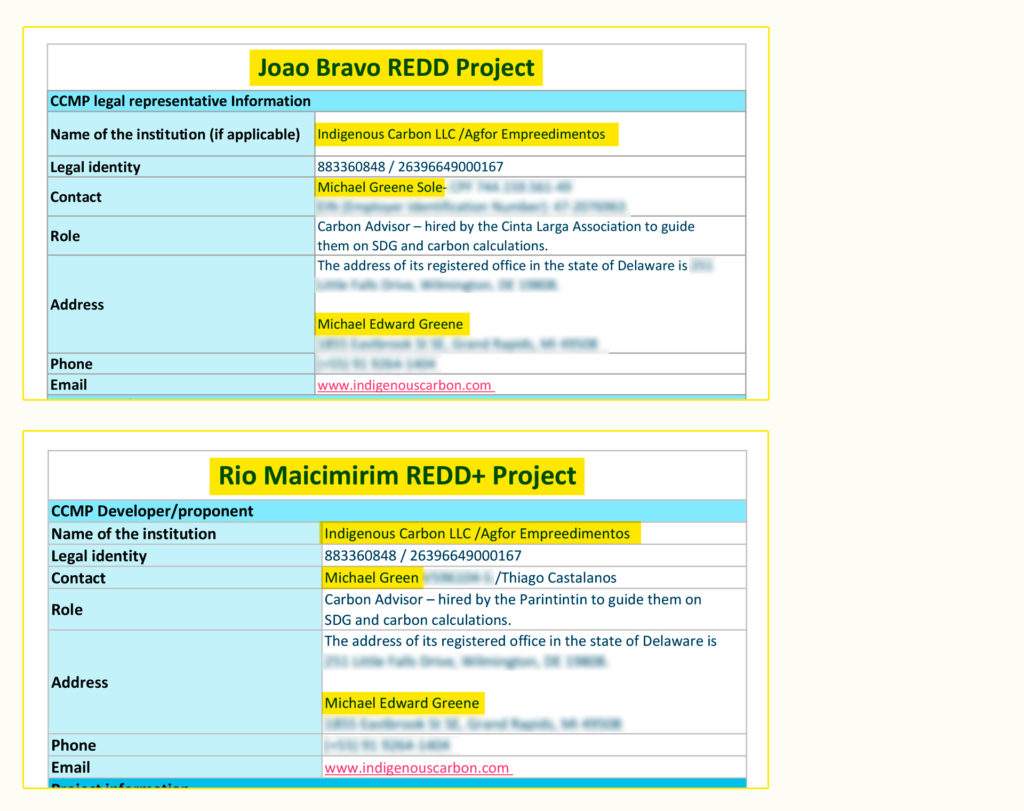

Of the 18 projects, six were certified between December 2023 and February 2024 and can therefore sell carbon credits to companies who want to offset their emissions. Greene’s name only appeared in connection with Indigenous Carbon when Cercarbono released the certification reports. In these documents, the businessman is cited as a “carbon advisor,” while the company is referred to as the “legal representative” of four of the certified projects and as the “developer and proponent” of the other two.

After certification, however, the Project Description Documents (PDDs) that are submitted when the initiatives are filed with the certifier were modified on EcoRegistry, the website Cercarbono uses for registration. In a new version of the PDDs for the six certified projects, Indigenous Carbon is no longer listed as the co-proponent, leaving only the Indigenous associations. In this version, Indigenous Carbon only appeared as providing “technical support” to the six projects.

In late May, another change was made: three of the PDDs where Indigenous Carbon did not appear as proponent were withdrawn, while a previous version remained, in which the company was indicated as playing this role. SUMAÚMA has copies of the original PDDs, where the company appears as a proponent, and also of the six PDDs where it no longer does. On the EcoRegistry website, Indigenous Carbon is no longer listed among the proponents of the six certified projects. The reason for these changes is unclear; they may have been made to avoid public exposure of Indigenous Carbon and minimize its role in the carbon projects—in Portel, Michael Greene claims he is the proponent of only one of the projects targeted by the Public Defender’s Office.

When asked by SUMAÚMA, the certifier Cercarbono said project “holders” can make this type of change. According to the certifier, the documents that prove this change will be checked when projects are re-verified, which happens every few years so new carbon credits can be generated. As Cercarbono defines the term, the holder is the project’s legal representative.

All Indigenous Carbon projects are audited by the Indian firm 4K Earth Science Private Limited, a private company hired by the project proponents to provide in-field validation of what is described in the PDDs and attest that they can generate the projected carbon credits. In the verification and validation reports for the six certified projects, in four projects the clients are the Indigenous associations plus Indigenous Carbon (João Bravo, Rio Maicimirim, Rio Jacareacanga, and Juina) and in two cases, the Indigenous associations alone (Rio Roosevelt and Ipixuna).

As required by Cercarbono in the validation and certification process, 4K Earth Science has filed declarations stating there is no conflict of interest between it and its client in eight projects registered by Indigenous Carbon. On all of these declarations, the company, which registered in the United States, was initially called the “holder” of the projects. The statements related to two of the projects were subsequently altered, so the Indigenous people alone appear as the holders of the Rio Maicimirim project and as co-holders of the Juina project, together with Indigenous Carbon.

In addition to the six certified projects, four of the 18 projects filed in 2022 and 2023 were retired from Cercarbono while eight are still being validated. The four that were retired had been proposed by Indigenous Carbon and the Kayapó people’s Mantinó Indigenous Association, of the Baú Indigenous Territory in Pará. Mantinó was founded in 2019 by a group that split off from the territory’s traditional association, the Kabu Institute. When contacted, Mantinó’s coordinator, Elissandra Soares, said the association had been approached by Agfor, another of Greene’s companies, but that they had not signed any carbon contract with the firm and that no services had been carried out in the territory. When asked about the documents submitted to the certifier in which the name of the association and its leaders appear, Elissandra again denied that Mantinó had signed contracts with Agfor or Indigenous Carbon and said “no company has been authorized to speak for” the association.

The negotiations with Indigenous territory associations were in fact initially conducted on behalf of Agfor Empreendimentos, a Brazilian subsidiary of Brazil Agfor, a company registered in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Both Agfor Empreendimentos and Brazil Agfor, as well as Greene, are among the defendants cited in the public civil lawsuits filed against these carbon projects in Portel by the Pará State Public Defender’s Office, in July of last year. In the Brazilian legal system, a public civil lawsuit is a legal instrument aimed at protecting collective interests. It is used to sue for damages to public and social assets, the environment, and consumers.

According to the indictment, three projects were set up wholly or partly on lands that are sites of state agro-extractivist settlements, on the basis of invalid property registrations. A fourth project, which was never certified, used anomalous records filed with the national environmental registry of rural properties, or CAR, which were canceled. Because of the lawsuit, the certifying company Verra suspended the sale of carbon credits from the three projects that had already been certified, under numbers 2252, 981 and 977.

Arguments are still being examined and defendants subpoenaed in the cases, and no decision has been handed down. The state of Pará and the Pará Land Institute are acting as assistants to the prosecution. The Federal Police have opened a confidential investigation into the matter, and those involved are being called to testify.

The Cinta Larga and Munduruku Indigenous peoples have signed contracts with Agfor Empreendimentos, according to documents seen by SUMAÚMA. In these contracts, Greene’s company was defined as the project developer. Later, the Cinta Larga’s contract with Agfor was replaced by contracts with Indigenous Carbon, now appearing as the “advisor” to the Indigenous associations. There are indications that a similar switch was also made with other ethnic groups. The switch occurred after November 2022, which is when the website Intercept Brasil reported that the carbon projects in Portel were overlapping with public lands.

In the Indigenous Carbon contracts seen by SUMAÚMA, Michael Greene is defined as the corporation’s “administrator.” The contracts stipulate that the company will keep 30% of the credits generated by the projects, considered standard on the so-called voluntary carbon market, an international market not ruled by government regulations.

Although Indigenous Carbon is named as advisor, the contracts state the company will have the “exclusive right to help find international and national buyers for the carbon credits.” According to attorneys consulted by SUMAÚMA, this means it can be held responsible if the credits it sells are questioned.

In one case, with the Cinta Larga of the Roosevelt Indigenous Territory, in Rondônia and Mato Grosso, the contract with Indigenous Carbon was signed on April 29, 2023, more than four months after the project applied for certification from Cercarbono.

Unlike the situation in Portel, the Indigenous association projects seemingly do not involve the theft of public lands, which is the illegal conduct underpinning the charges brought by the Pará State Public Defender’s Office. Although their territories belong to the nation of Brazil, Indigenous peoples have the exclusive right to their use. However, while projects on the voluntary market are governed by private contracts, they still must comply with Brazilian legislation, in terms of both property rights and the rights of the communities living in the territories where the credits are generated.

Voluntary market, rights, and legal uncertainty

On the voluntary carbon market, companies voluntarily purchase credits to offset their greenhouse gas emissions in order to reduce their environmental footprint, improve their public image, or respond to shareholder pressure. This is different from what happens on regulated markets, where governments set emissions ceilings for companies. In this case, companies that have emitted less than the ceiling can sell credits to those that have exceeded it.

In Brazil, and especially in the Amazon, projects on the voluntary market generate credits from what is called “avoided deforestation,” basically, a promise to reduce emissions caused by deforestation. These are known as Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation projects, or REDD+, a mechanism created under the U.N. Convention on Climate Change. Initially designed to remunerate countries for conserving their forests, the mechanism is now used on the voluntary market as well. In this case, proponents must prove that their projects will help reduce deforestation in comparison with what would otherwise happen, if their business didn’t exist. This is why most such projects take place in areas of preserved forest that are under pressure from deforesters. If well executed, these projects can yield financial resources for the Indigenous and traditional communities who care for the ecosystems that play a strategic role in climate crisis mitigation.

Because the companies that are developing carbon projects are putting pressure on Indigenous territories and extractivist reserves, where Nature is generally more conserved, the Lula administration, Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, and Public Prosecutor’s Office of Pará have suggested rules for contracts on the voluntary market that would reinforce the protection of the rights of the populations living in these territories.

A 2018 resolution by the National REDD+ Commission, linked to Brazil’s Environment and Climate Change Ministry, defined some rules in this regard. In 2023, the government included an article detailing socio-environmental safeguards for voluntary market projects on Indigenous and community lands as part of a draft bill to establish a regulated carbon market in Brazil. The bill, however, awaits a new vote in the Senate after suffering changes in the Chamber of Deputies. While members of the lower house kept the safeguards in place, they also added some controversial clauses to the proposal that would enable agribusiness to sell carbon credits generated by REDD+ projects on the regulated market, without being subject to any emissions ceiling.

The safeguards provided for in the bill stipulate that populations involved in the projects must approve the contracts as the result of a free, prior, informed consultation, pursuant both to Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization and to Brazilian law. According to the text, this consultation process should also comply with the terms of any existent community consultation protocol or plan. In addition, the process should be supervised by either the Indigenous Peoples Ministry, the federal agency of Indigenous affairs Funai, or the Indigenous Populations and Traditional Communities committee of the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office.

The safeguards also state that money obtained from carbon credit sales must be deposited in “specific accounts”—that is, accounts established for this sole purpose—and the contracts must guarantee a “fair and equitable” distribution and “participatory management” of the funds. Furthermore, the contracts must include a clause providing for the compensation of populations “for collective material and immaterial damages” that may arise from carbon projects.

Some of the safeguards are also recommended in a so-called technical note released in July 2023 by the Public Prosecutor’s Office of Pará and the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office to guide their attorneys in cases of carbon projects on Indigenous and community lands. The technical note suggests that the free, prior, and informed consultation process should not only be supervised by public authorities but also conducted by them.

The document also says that carbon contracts should be public and registered at official records offices (something the draft bill does not stipulate) and recommends that they include a “flexibility clause” to allow for their revision at a community’s request.

Indigenous Carbon’s contracts state that Indigenous associations must pay a fine of 20% on the 30% of credits belonging to the company if they break the agreement “without cause” after the projects have been certified. The contracts fail to make clear what might be considered “without cause,” but they do specify that not selling credits or selling them for less than expected is not a valid cause, since the carbon market is challenging and volatile.

While the technical note is based on current Brazilian legislation, it is not legally binding.

‘Consent’ by the Indigenous affairs agency

To complicate matters, the Indigenous Carbon projects were negotiated in 2021 and 2022, during the administration of far-right president Jair Bolsonaro (Liberal Party). At the time, the Indigenous affairs agency Funai had been practically abandoned, some of its regional coordinating offices occupied by members of the military, and illegal mining was being encouraged in Indigenous territories.

All Project Description Documents registered with Cercarbono mention Funai as an “interested party,” and some state that the agency took part in project-related meetings and events. Three contracts between Indigenous Carbon and the Cinta Larga that were submitted to the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office as part of the administrative process opened in Rondônia say that Funai gave its “consent” to the consultation process that approved signing. But there are indications that there was no rigorous monitoring by the agency.

The administrative process was opened in February 2023 to monitor carbon project negotiations, following a meeting in the town of Cacoal in which Cinta Larga leaders informed the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office that they had signed a contract with Agfor the previous year. The leaders said they were being threatened by miners and loggers “because of the possibility of carbon credit sales.” At the time, they also said that Cinta Larga of the Aripuanã Indigenous Park were negotiating with Carbonext, another carbon project developer. At the time, however, Indigenous Carbon had already registered five projects in the Aripuanã Indigenous Park with Cercarbono.

At the next meeting, in August 2023, the Cinta Larga presented the contracts with Indigenous Carbon, digitally signed by Michael Greene. On this occasion, they said they had no prior consultation protocol and had not been accompanied by their own attorney during negotiations with the company, but that the then-regional coordinator of Funai in Cacoal, Sidcley Sotele, had been at the meetings. The Public Prosecutor’s Office then advised the Indigenous people to have an attorney analyze the contracts.

Sidcley Sotele was dismissed from Funai’s regional coordination in January 2023, early in the new Lula administration. Sotele, formerly agriculture secretary in Cacoal, told SUMAÚMA that although he had been appointed under Bolsonaro, his name had been suggested for the post by the Paiter Suruí, another Indigenous people in Rondônia.

Sotele said he had attended two carbon project negotiation meetings at the request of the Cinta Larga, but that he had only sat in. “That’s how I followed the process, without the power to speak. They didn’t ask for any guidance; they just wanted me to be there,” he claimed. He said he couldn’t guarantee there had been any prior consultation, apart from the meetings between Cinta Larga leaders and representatives of Agfor, because he left Funai “and they continued the talks.” He also said he was unaware of the contracts with Indigenous Carbon.

The former Funai coordinator doesn’t believe the carbon projects on Cinta Larga lands will be able to move forward, since mining continues, “albeit disguised.” “If the Public Prosecutor’s Office or some other agency doesn’t intervene, demanding explanations [about the projects] and how things are being done, things won’t move forward,” he said.

SUMAÚMA tried to hear two Cinta Larga leaders who signed contracts with Indigenous Carbon, Raimundo Cinta Larga and Gilmar Cinta Larga. Raimundo said he would have to speak to his community before giving an interview; Gilmar wanted to know about the “intent of the report” and whether it would be “negative.” In a second contact, SUMAÚMA sent questions via WhatsApp but received no reply. Thalia Assiry Cinta Larga, president of the Cinta Larga Indigenous People’s Development and Production Cooperative, or Cooperbravo—which appears as a proponent on some of the projects, along with Indigenous Carbon—said via WhatsApp that she would first have to consult with the group’s lawyer, but she didn’t say who that was.

In December 2023, four months after the August meeting, the Cinta Larga met with the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office again and promised to set up a “territorial monitoring project” to put an end to illegal activities inside their territories. They then introduced an attorney for Cooperbravo, Karen Roberta Miranda de Sousa Falcão.

The attorney submitted a statement in which she says the contract signed with Indigenous Carbon is “fair and compatible with Brazilian and foreign carbon market regulations.” The document also says “the final decision” on signing the contract “was taken during a meeting chaired and coordinated by the Indigenous people, observing their own traditions, as stipulated in regulations safeguarding the rights of Indigenous people.”

Karen Falcão is also an attorney for the Association of Parintintin People of the Ipixuna Indigenous Territory, which was founded in January 2024. Following certification of the carbon project in the Ipixuna Indigenous Territory, in Amazonas, in December 2023, the Parintintin association was listed in the EcoRegistry as a proponent, alongside the Organization of the Parintintin Indigenous People of Amazonas, or Opipam. Thiago Castelano, a member of the Parintintin people and association coordinator, said he could not give an interview without consulting with the population of the territory and asked SUMAÚMA to speak to their attorney. Castelano is listed as Indigenous Carbon’s contact on the certification reports for four projects: two with the Parintintin, one with the Cinta Larga, and one with the Munduruku.

In regard to questions sent by SUMAÚMA via WhatsApp, Karen Falcão said the report’s approach was “invasive” and based on “positions taken in advance.” According to the lawyer, the Indigenous people in the Ipixuna Indigenous Territory would first have to “decide if they wanted to give an interview and how they wanted to do so,” in accordance with their consultation protocols. Lastly, she said the interview could only be done in person, in the territory.

The project in the Ipixuna Indigenous Territory is the only one in the EcoRegistry that shows it has already sold credits: 17,605 of the over 2.5 million available. The buyer was GreenLand Investments S.A.S., a Colombian group of agribusiness firms that own banana and avocado plantations. The price of each credit generated by a REDD+ project varies greatly, depending on the year in which the corresponding carbon emission was avoided. During the last quarter of 2023, this price averaged USD 3.76 for 2017 credits and USD 13.71 for last year’s.

In 2021 and 2022, carbon project negotiations in both Parintintin territories—Ipixuna and Nove de Novembro—were conducted by the Organization of the Parintintin Indigenous People of Amazonas. Raimundo Parintintin was the association’s coordinator at the time, but since May 2023, he has been serving as regional coordinator of Funai in the Rio Madeira region. He told SUMAÚMA that his contacts were with Agfor and that he wasn’t even aware that a company called Indigenous Carbon had registered the projects with the certifying body. At the time, Raimundo said, Agfor hired some Parintintin Indigenous people to carry out the projects.

Raimundo said he signed the contracts under pressure from members of his ethnic group. “I didn’t feel very secure at the time, because there was no participatory construction, no consultation, how things would work, the division [of the money],” he explained. “Since I’m from the [Indigenous] movement, I know it’s not very easy, when people come along deceiving Indigenous people, [saying] they’ll make a lot of money. Folks get excited. They said there would be social matters, that they’d build schools, houses, before the project started selling carbon credits. But businesses work on profits. How are they going to invest in something without being sure it’ll work out? Nothing that was talked about then is happening.”

According to Raimundo, there wasn’t exactly a prior consultation with the population but rather a meeting. Under the current administration, the Indigenous Peoples Ministry held a seminar on REDD+ in Brasília, and Funai staff were told to monitor carbon talks closely. At the time of negotiations with Agfor, Army captain Claudio Rocha was Funai coordinator in Rio Madeira. According to Raimundo, the Parintintin met with him to advise about the project, and company representatives also spoke with Rocha. “But there was no effective, direct participation on Funai’s part,” he said. “What [Funai] said was: ‘If it’s good for you, go ahead; we don’t want to get in your way.’”

Domingos Parintintin, current coordinator of the Organization of the Parintintin Indigenous Peoples of Amazonas, asked SUMAÚMA to speak with Joel Joveliano Parintintin, the association’s executive secretary. Joel in turn directed us to the press secretary, who asked for the questions via WhatsApp but did not reply with any answers

Attorney Adriano Camargo Gomes provides legal advice to the National Council on Extractivist Populations, which has been dealing with the matter of carbon project proposals in community territories. Given that Funai’s actions can change depending on the administration in power, he thinks it would be safer to recommend that negotiations be monitored by national bodies with ties to the communities, such as the National Council on Extractivist Populations or the Alliance of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB).

“We can’t treat communities like they’re incapable of expressing their wishes, but we have to recognize that there is an imbalance in terms of legal and technical knowledge compared to companies that have a lot of resources,” argues Adriano Gomes. “Precisely to avoid this imbalance, communities need to have advisory assistance. Calling in [the Alliance of Indigenous Peoples] or [the National Council on Extractivist Populations] is a low-cost remedy for solving the problem.”

SUMAÚMA asked Funai if it was aware of the 18 Indigenous Carbon projects, if the agency had in fact given its consent, and if it considers the contracts valid. The Indigenous agency did not respond.

Munduruku women against an association

The Munduruku Indigenous Territory is the most populous of the territories involved in Indigenous Carbon projects, with a population of 9,282, according to the 2022 census. Illegal mining has caused a rift between caciques and associations there, with Wakobor?n, a women’s association from the Upper Tapajós, leading the opposition to the Pusuru Indigenous Association, which negotiated with Michael Greene’s companies. It was because of a document issued by Wakobor?n, in January 2022, that the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office in Santarém opened a civil inquiry to investigate REDD+ projects in the Indigenous territory.

Initially, the inquiry was not related to the companies of which Greene is a partner or which he represents. The women filed their complaint about a Carbonext project on a ranch near the territory. What the Wakobor?n association had noticed was that the ranch belonged to a company owned by Leonel Babinski Marochi, who had been accused of public land theft in the community territories ofMontanha and Mangabal (the illegal land deeds were canceled by the courts). In September 2022, however, Carbonext reported this project had been suspended, precisely because of the questions raised about ownership of the land where it was to be implemented.

The investigation then turned to the arrival in the territory of another carbon company, at that point unidentified. At a meeting with the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office in October 2022, Maria Leusa Munduruku, then Wakobor?n coordinator, said she had learned that a group of Indigenous people was consulting about an agreement. She said the group claimed that each family would receive a salary and would no longer need to plant food. “The Indigenous people are worried; they know this isn’t a consultation, but that it harms them by pitting [one member of the group] against another,” she said at the meeting. The prosecutors pointed out that the Munduruku have a consultation protocol and that it should be followed before any contract is signed.

Only at the end of 2022 did it emerge that the Pusuru Indigenous Association had signed a contract with Agfor Empreendimentos. That is when Funai, at the request of the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, provided two documents: the minutes of a meeting organized by the Pusuru association and held on September 12, 2022, which had approved the contract, and a copy of the contract itself, likewise dated September 12, 2022. At the time, Funai’s regional coordinator in Tapajós was José Arthur Macedo Leal, who had spoken out in favor of mining on Indigenous lands. When the documents were submitted in December, four of the five projects in Munduruku territory were already being filed with Cercarbono, not by Agfor, but by Indigenous Carbon—the fifth was filed later, in January 2023.

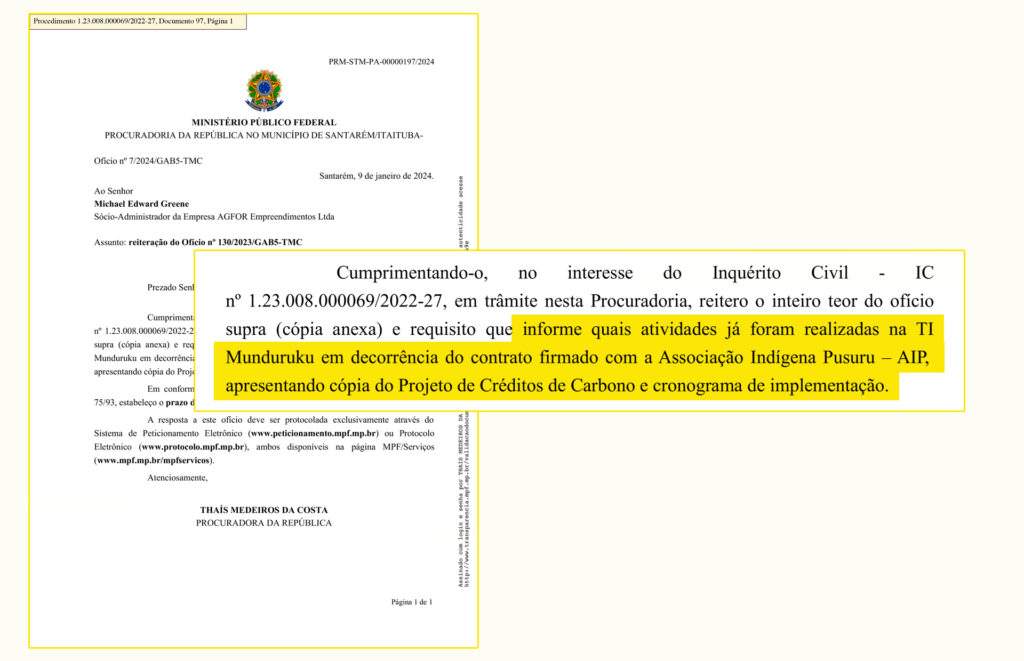

During this inquiry, the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office sent three official letters to Michael Greene, asking for information about what his company had already done in the Munduruku Indigenous Territory. The letters also asked for a copy of the carbon project plan and a timeline for its implementation. The last letter was sent in January 2024, but Greene never replied.

The five PDDs (Project Description Documents) about Munduruku lands have a peculiarity: they all report there was “unanimous” consent for four projects, but only 80% approval for one of them, and in the latter case the disapproval came from villages and lands where people had been excluded from the project.

Ediene Kirixi, current coordinator of Wakobor?n, disagrees. She told SUMAÚMA that the Munduruku consultation protocol was not followed and that the women’s association and five other associations who did not subscribe to the agreement were excluded from the process. “A group of Munduruku got involved in this project and were deceived by the food assistance, by the promise they were given of benefits,” she said. Ediene also says many caciques have asked about the money the company provided for implementation: “They ask if it’s true this money had arrived, and we don’t have a sure answer. We haven’t seen it.”

Following a request from the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office for information on activities carried out with Agfor Empreendimentos in the Munduruku Indigenous Territory, the Pusuru association submitted an “account report” on what it supposedly received as a result of the carbon project in 2023. The report includes “transfers” of just over BRL 238,000 (approximately USD 47,600). Most of the money, according to the table presented, was spent on rent for the association’s headquarters in Jacareacanga, payment of overdue electricity bills, gasoline, chartering motorboats, and bus maintenance, as well as chicken, rice, and other foodstuffs, including the purchase of two head of cattle for a “graduation.” There was also the payment of a “stipend” to four Munduruku and attorney fees.

The current Pusuru coordinator, João Kaba, was elected in March 2024. He replaced Francinildo Cosme Kaba, who negotiated the contract. João, who is a professor of Indigenous education, told SUMAÚMA that he has not yet had time to familiarize himself with the carbon accounts, but that he intends to continue with the projects at the request of the caciques. “Carbon credits protect the forest, replacing mining. They stopped doing these things and asked us to look for a project that doesn’t destroy. It seems like the only solution,” he said.

João Kaba noted, however, that the money received so far is very little in proportion to the population on Munduruku Land. “It seems these social assistance things were done, which I figure was the delivery of food assistance. Since the association doesn’t have a building, it also had to pay rent,” he said.

The amount the Pusuru association recorded in the accounts presented to the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office matches the accounts kept by Waldelírio Manhuary, former coordinator of the projects on Munduruku Land. Known as Waldé, he said he is not part of the association but was asked to work with the carbon credits because he is “highly articulate” and speaks Portuguese well. A resident of Jacareacanga, Waldé has been formally charged with an offense that in the Brazilian justice system can involve receiving, selling, transporting, or concealing the proceeds of a crime. The charge is linked to his alleged complicity in illegal mining. He says he has not yet been subpoenaed to testify in the case.

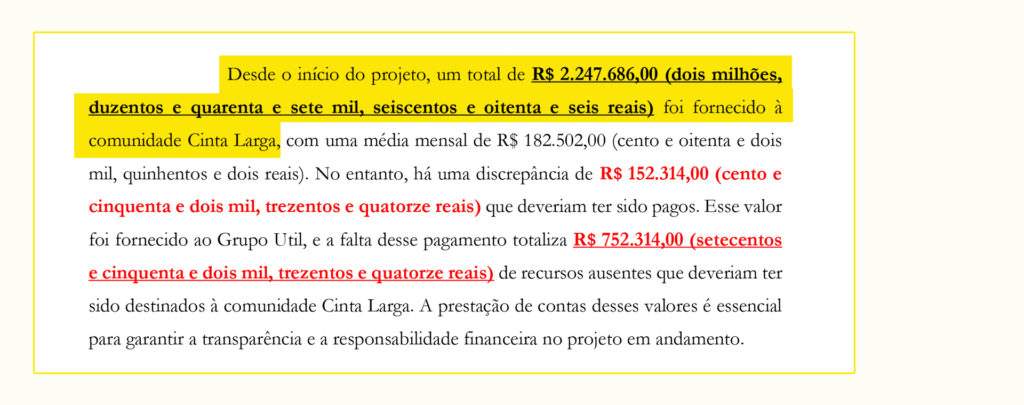

Waldelírio Manhuary worked on the projects until March 2024, when, he told SUMAÚMA, he had a disagreement with Michael Greene and was dismissed. Only then, he said, did he look for Indigenous Carbon’s registration but could not find it. Waldelírio said the rift occurred because he disagreed with the value of the carbon credits stipulated in “pre-sales” by the Munduruku to Greene, who bought them on behalf of Brazil Agfor. These credits would then be resold by Greene.

According to two pre-sale contracts SUMAÚMA was given access to, Greene supposedly bought a total of 32,000 credits in 2023, for a dollar and a half each—which corresponds to the USD 48,000 (approximately BRL 238,000) that the Pusuru association recorded as money transferred in. Also according to Waldelírio, when Greene submitted a third contract with the same value for the credits this year, he didn’t accept it, because the agreement in the carbon project negotiations was that each credit would be sold for five dollars. “He said sale negotiations had been difficult and it was only possible to sell a few credits,” the former project coordinator said.

Waldelírio Manhuary said that even now, when he is no longer working with the carbon project, he has been contacted by caciques who are unhappy with the way the deal is going. “In the meetings I held in the villages [during the negotiations], I said the project was going to work out, that they would benefit. But the caciques who signed [the contract] haven’t received a penny. So they want the contract to be revoked, to be halted, because there has been friction, social problems, among them,” he said.

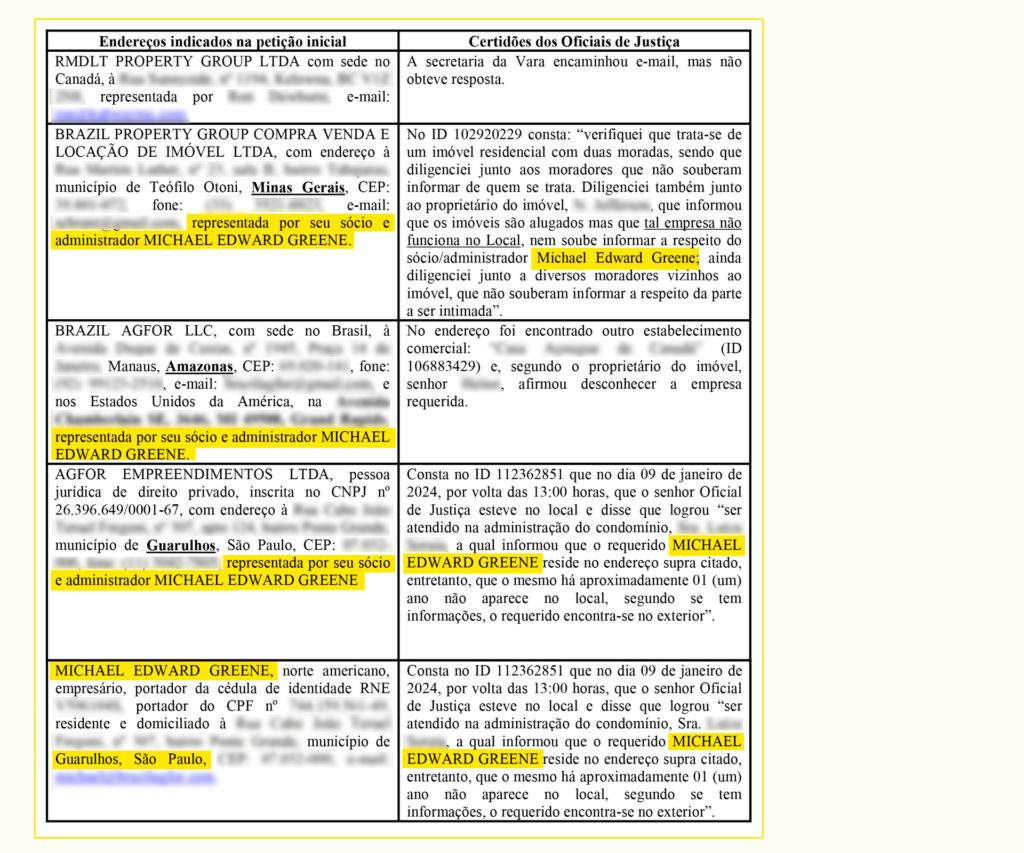

Waldelírio also said he used to hold a weekly video conference in which Michael Greene, who lives in the United States, took part with the help of an interpreter. He said he only met the U.S. entrepreneur in person once, at a meeting in São Paulo in May 2023, to which several Indigenous people were invited. Greene has an address in Guarulhos, São Paulo, but court clerks who went there in January 2024 to subpoena him for one of the Portel lawsuits were informed that he hasn’t been there for about a year and is out of the country.

Several people who worked for Greene said they never met with him in person, that instructions were given over the phone or in video conferences, and that his wife, Evelise da Cruz Pires Greene, sometimes also took part.

Portel, where everything started but nothing has ended

A target of the Public Defender’s lawsuits against four carbon projects in Portel, Greene is waging a parallel war in the courts against former service providers he hired in Brazil.

Last February, the U.S. businessman filed a lawsuit in Belém asking for an accounting of the money that one of his companies, Brazil Agfor, claims to have passed on to another company, Útil Serviços em Vigilância e Segurança Privada Ltda., belonging to Diego Tavares Pereira. Registered in 2013 in Belém, Útil is classified as a “small business,” with capital stock of BRL 400,000 (around USD 74,000). The lawsuit alleges that, starting in 2022, Brazil Agfor transferred more than BRL 13.4 million (almost USD 2.5 million) to Útil, while the company had reported BRL 10.4 million (around USD 1.9 million), resulting in a difference of almost BRL three million reais (around USD 550,000).

In the text of the lawsuit, Brazil Agfor is described as an “agent of change” in the Amazon and Greene as “an individual with deep ties to Brazil.” In Portel, he became known for his promises of social works. Speaking to the website Quantum Commodity Intelligence, which provides market information and in 2022 described Indigenous Carbon as a “mystery company”, Michael Greene said he was in negotiations with the “Brazilian development bank” regarding a program to reduce poverty in the Amazon. In a message to the Portel City Council, Greene stated that he is the largest developer of REDD+ projects in Latin America and that his business represents 50% of the carbon credit market in Brazil.

In contrast to these statements, the lawsuit against Útil suggests that the expenses related to Greene’s carbon projects in the Amazon were not paid directly by his companies, although he appears as a partner or administrator of at least ten firms registered in Brazil, including Agfor Empreendimentos. Greene supposedly passed the money on to Útil to cover the costs of the Portel projects as well as those on Indigenous lands.

Greene and his company Brazil Agfor claim in the lawsuit that a total of almost BRL 2.3 million (around USD 460,000) was spent on projects in Cinta Larga territories; BRL 518,000 (around USD 104,000) on projects in the Baú land of the Kayapó; and more than BRL 499,000 (around USD 99,800) on projects in Parintintin and Munduruku territories. There is a list of 37 people who allegedly received payments to carry out the projects, most of them Indigenous Munduruku and Parintintin. On some receipts seen by SUMAÚMA, the company making the payments is Amigos dos Ribeirinhos Assessoria Ambiental, one of Greene’s companies, registered in 2020 with capital stock of BRL 140,000 (approximately USD 25,800). The monthly amounts range from roughly BRL 1,400 to BRL 4,000 reais (around USD 250 to USD 735).

Diego Tavares Pereira told SUMAÚMA that Útil has still not been notified of the lawsuit filed by Greene. In December 2023, Útil sent a letter to Greene and Agfor terminating their services. The letter cites delays in payments Greene was supposed to make for security services provided by the company. The letter also mentions unfulfilled promises that Útil would have surveillance posts on Indigenous lands and says that “as of now, this work hasn’t begun.”

Pereira is also the defendant in one of the lawsuits brought by the Public Defender’s Office, relating to the Ribeirinho REDD+, project, the only one in Portel that was never certified by Verra, and therefore never sold credits. Pereira became the target of the lawsuit because he was president of the Association of Ribeirinhos and Residents, one of the project proponents. Contrary to what its name suggests, the association is not community-based but a private entity, created in 2018 with an address in São José dos Campos, São Paulo state.

In his response to the Public Defender’s lawsuit, Pereira claims he only took over the presidency of the Association of Ribeirinhos and Residents in October 2022, at Greene’s request, after the project was filed with Verra. Before that, according to documents presented by the defense, Greene himself was the president of the organization. Pereira also accuses the U.S. entrepreneur of being part of a carbon industry “orchestra of fraudsters and cowboys” and claims that he was duped by him. He says he is at the disposal of the courts to “clarify the facts and assign responsibility.”

Michael Greene is also suing contractor Miguel Rocha, owner of Agape Serviço e Representação Ltda., from Belém, alleging breach of contract. The company was contracted to build five schools, all, according to Rocha, within 12 hours of Portel. The contractor claimed to have delivered one completed school and finished 85% of another. But he said that complicated logistics, including river transportation of materials and changes he had to make to the projects to meet legal specifications, prompted him to ask to renegotiate payment. Rocha claims that Greene owes him more than BRL 780,000 (around USD 143,350), which he had to spend out of his own pocket.

But Michael Greene apparently still has some allies in Portel. Last March, an association claiming to represent the residents of an agro-extractivist settlement filed a lawsuit against Verra asking for BRL 40 million (around USD 8 million) in damages for the suspension by the certifier of the Rio Anapu-Pacajá REDD+ carbon project, whose proponent is Brazil Agfor.

The association argues that the population in the settlement was benefiting from work by Greene’s company, which was building schools and health centers and sinking wells; they don’t say whether they received part of the value of the credits directly, as should happen in the case of community lands. The lawsuit was filed with the Agrarian Court of Castanhal, the same court as the lawsuits brought by the Public Defender’s Office. Two other associations have brought similar lawsuits, asking for the same amount of damages.

Michael Greene doesn’t respond

SUMAÚMA tried to contact Michael Greene in June 2024 by phone, via WhatsApp and Signal messages, and through his and Brazil Agfor’s known emails but received no responses to questions posed about Indigenous Carbon’s projects. The reporter also tried to contact the Lopes Pimenta law firm, owned by attorney Leonardo Lopes Pimenta, who signed Greene’s lawsuit against Útil as well as the challenges he and his companies have filed against the Pará Public Defender’s Office’s lawsuits regarding the carbon projects in Portel. However, calls made to the cell phone that appears as the contact number on the Advocacia Lopes Pimenta website went to a recorded message that said the number was blocked, and messages sent to the email bounced back.

In the carbon projects with the Indigenous people, there is a contact telephone number in São Paulo, but no one answers or responds to WhatsApp messages. Another phone number is for Diego Tavares Pereira, who no longer works for Greene; Pereira said he was unaware his phone number was listed in the projects and learned about it from SUMAÚMA. The addresses included in the projects are those of the Indigenous associations, and the website www.indigenouscarbon.com did not exist at the time this article was published.

Greene and his companies have filed challenges to three of the Public Defender’s four lawsuits, and SUMAÚMA has copies of two of them, both relating to one of the projects, Pacajaí REDD+. In the documents, they state they have no involvement in the management of the Pacajaí project and that they only act as advisors in another (Ribeirinho REDD+) and as managers in a third (RMDLT). Michael Greene and his companies appear as proponents and managers in only one project, Rio Anapu-Pacajá REDD+, according to these challenges. These documents also question whether the Public Defender’s Office can legitimately act in matters involving land ownership and allege that the office does not have the “proper mandate” to act on behalf of the populations of the settlements where the carbon projects overlap with public lands.

The challenges also assert that, despite this overlap, the properties used for the carbon projects “are privately owned.” At the time the Public Defender’s Office started the lawsuits, 45 of the 50 private property registrations used to register the three projects already certified by Verra had been canceled. The remaining five did not overlap with state settlements. Greene argues that he received the registrations held in his name as payment for a debt. The challenges also claim that it is not within the purview of the Brazilian courts to adjudicate issues involving the carbon market, “which lacks specific regulation in the Brazilian legal system.”

In October 2023, in a written response sent to the website G1, which published reports on the Public Defender Office’s lawsuits in Portel, Greene said he had received the properties “in good faith” and that he would cooperate to “adjust whatever is not legally compliant and comply with any and all applicable judicial determinations.” Now, on his LinkedIn page, he accuses “a public official” of using “trumped up charges” to “help her corrupt friends steal all the land” on which his projects are located—an unsubstantiated accusation against the public defender who signed the lawsuits, Andreia Macedo Barreto.

The Pará courts tried to subpoena Greene and three of his companies to make a statement about the lawsuit they have not yet contested but were unsuccessful. Subpoenas sent to the U.S. entrepreneur and three of his companies were returned. In addition to finding that Michael Greene was not at his address in Guarulhos—also listed as the address of one of his companies, Agfor Empreendimentos—the court clerks serving the subpoenas found that the other two companies were not operating at the addresses indicated at the time of registration. A butcher’s shop was located at the Manaus address for Brazil Agfor, which is based in the United States. There was a private residence at an address for Brazil Property Group in Teófilo Otoni, Minas Gerais.

Public defender Andreia Macedo Barreto, who brought the lawsuits, wrote that the non-verifiability of the addresses means these companies are “a simulacrum [false representation] of their operation in Brazil, certainly part of the illegalities and fraud aimed at the illicit appropriation of public lands and forests in the Amazon.” In the challenges he has filed, Greene now only provides U.S. addresses for Brazil Agfor and Agfor Empreendimentos. This will force the Brazilian courts to subpoena him by letters rogatory, a type of formal request to the justice system of another country.

While the investigations into the Portel case continue, Indigenous Carbon’s projects add even more elements of distrust in a market that lacks transparency and where the expectations of those who most need to be rewarded for the work they do to conserve Nature often turn to disappointment.

Opaque Carbon is a project on how the carbon market is working in Latin America, in partnership with Agência Pública, Infoamazonia, Mongabay Brasil and Sumaúma (Brazil), Rutas del Conflicto and Mutante (Colombia), La Barra Espaciadora (Ecuador), Prensa Comunitaria (Guatemala), Contracorriente (Honduras), El Surtidor (Paraguay), La Mula (Perú) and Mongabay Latam, led by the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (CLIP). Logo design: La Fábrica Memética. Legal review: El Veinte