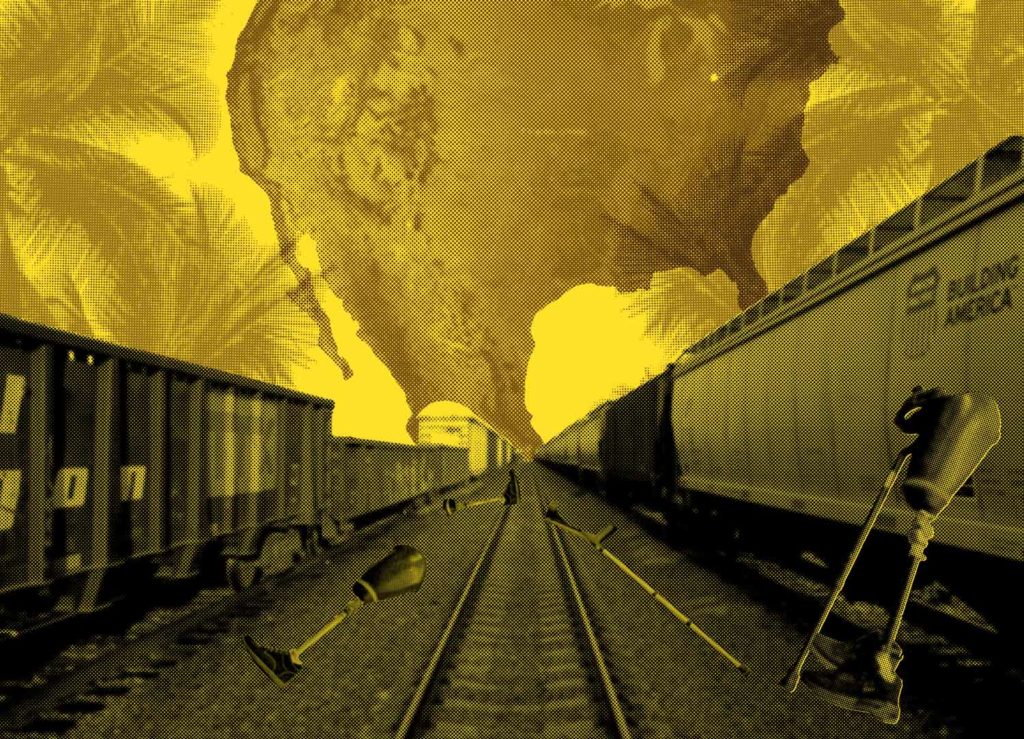

The Beast, the north-bound train that crosses Mexico, has maimed hundreds of migrants over the last decade. Despite this, migrants fleeing from five continents have no other choice but to ride on its back to reach the U.S. While most victims used to be from Central America, migrants from Venezuela, Haiti, Cuba, and other countries have also fallen prey to The Beast. For many, losing a limb is the end of the road, but others continue their journey north.

Text: Bryan Avelar

Photography and video: Paula Villela

Irapuato, Mexico/ Choluteca, Honduras

I. Encountering The Beast

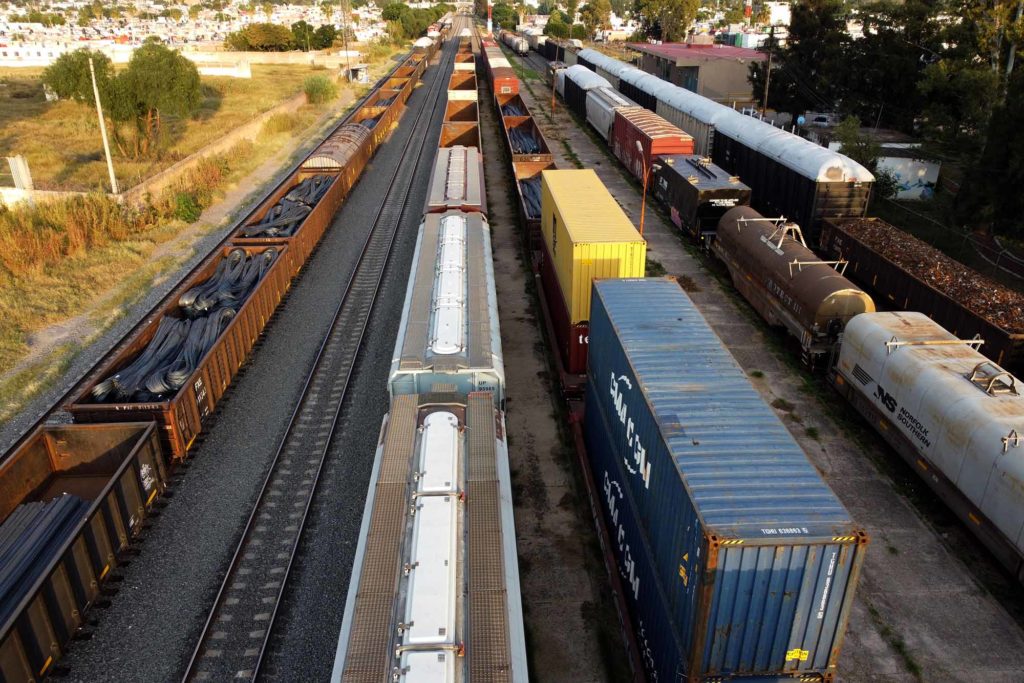

A hoarse whistling comes from the dark, and the ground shakes as The Beast gets closer. It hisses as it pulls the freight cars that clash with each other, roaring like an old metallic animal that tries to bring itself to a halt. Dozens of migrants are hiding under a bridge a couple of meters away from the railroad. They have been protecting themselves for hours from the cold that this evening in Irapuato, Mexico, has brought. It’s 8 degrees Celsius outside, and their hands and faces are in pain. They are also hiding from robbers, rapists, kidnappers, and migration officers who prowl near the rails. On hearing the train is arriving, they come out of their hiding place and adjust their worn-out backpacks.

Migrants gather in small groups near the rails and give each other advice on how to board the train. Their accents give their nationalities away: some of them come from Honduras, Nicaragua and El Salvador, while others from Venezuela and Colombia. There’s also a group of Cubans who seems apprehensive as the train arrives. They are all part of a record-breaking migratory flow heading to the U.S. In 2023 alone, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) registered 782,176 encounters with undocumented migrants in the U.S. Once they arrive at the U.S.-Mexico border, they will make the headlines. But tonight, standing next to the rails, they are anonymous.

The train will stop soon, but a Venezuelan man in his thirties, with a bony face and sunburned skin, wants to test his agility. The journey has its own rules, and he knows it takes refined skills to ride this animal. He holds his hand close to the iron, getting a sense of the speed as it touches his fingers. Fear is reflected on his face. He knows if he slips, or if he doesn’t get a firm grip, the train will claim an arm, a leg, or his life.

“You coward!” yelled a group of Hondurans who were huddled together for warmth several meters behind him.

“You try then!” The Venezuelan man said defiantly. They don’t utter a word; they know the risks too.

He comes closer to the rails, firmly places his cap backwards and rolls up his sweater. He runs alongside the train, which is moving slowly, and grabs one of the handrails with both hands. His legs hang for a few seconds while he swings until he manages to step on the last rung. The train advances, and his silhouette fades in the dark.

Part of the Honduran group applauded with merriment the efforts of the Venezuelan man, whom they had challenged a few moments before. Others simply watched in awe and shock.

Migrants’ greatest fear on this evening of November 2023 is not the cold at night or the heat during the day; nor being caught by security personnel from Ferromex, the company that owns the trains; nor being robbed by criminal groups who control the routes; nor being stranded in a shelter at the mercy of criminals in one of the most violent cities in the world. That comes later. Their greatest fear right now is being devoured by The Beast.

“What happens if you let go of the train?” I ask one of the Hondurans.

“You’re fucked,” he says while shivering with cold. “If you let go, The Beast will suck you in, ripping your legs and arms. It tears you to pieces.”

Although this is his sixth journey on the train in a month, he’s afraid, he says.

“The fear never goes away, but we don’t have a choice. The wall is not coming to us. We have to keep moving,” he adds.

Migrants know that riding on The Beast is the only way of moving fast toward the U.S. without paying. The second option is to walk almost 1,800 kilometers from Tapachula, a city close to the Guatemalan border, to Matamoros or Reynosa, two border cities in northern Mexico. The third option is to take buses, getting off the bus before each checkpoint and walking around it through the thickets. These dynamics compel migrants to get away from other people and risk their lives on the back of The Beast.

II. Attacked by The Beast

“I had seen trains before, but this one was impressive,” says Jerónimo Pérez, a 23-year-old amateur salsa dancer and novice tiktoker from Venezuela, recalling his first encounter with The Beast.

In June 2023, Peréz was in the outskirts of Mexico City, in a place known as El Basurero, where hundreds of migrants were waiting for the train to leave. Many of them also hailed from Venezuela, a country that saw the exodus of more than 4 million people between 2015 and 2022 and whose citizens constitute the fifth largest group of migrants seeking asylum in Mexico and the U.S. Some of them showed Pérez how to board the train.

On his first trip, the train made a halfway stop, and security guards fooled them into getting off the train: “We had to wait for the next one,” he said. The second time he boarded the train, he recalls the cold: “I felt I was going to freeze.”

Upon arriving in Irapuato, he got off the train and hid underneath a bridge near the rails. The following morning, a group of volunteers from the NGO Amigos del Tren welcomed him to the shelter, where he could use the restroom, take a shower and eat.

Before boarding The Beast for the third time, Pérez rested and went out the following day to earn some money to get back on the road. He boarded the first bus he saw to tell jokes to passengers. “I like to make people laugh. I enjoy it very much and I get paid for it,” he said.

One of the passengers gave him a bag with food instead of money, but he happily accepted it and got off the bus. “Then I saw my friends waiting for me at the other side of the rails, but the train was just arriving. It was right between us.”

As soon as the train stopped, he held the bag with his teeth and started climbing it to get to the other side. When he got to the top, The Beast jolted, starting abruptly and pulling the freight cars beneath Pérez. He then fell to the ground while the train was picking up the pace.

“It was strange because I felt agonizing pain. But I didn’t feel anything after a few seconds. It was like being in a dream,” he recalls.

One of his friends dragged him out of the rails. Pérez’s memories then become confusing. He remembers a hospital, blood, and darkness.

“I woke up with only one leg,” he said.

This would not be his last encounter with The Beast. But for many, losing a limb is the end of the road.

III. Learning to walk again

In Honduras’ Choluteca department, near the border with Nicaragua, at about 2,000 kilometers from Irapuato, there’s a small, modest house in an alley where hope is brought back to those who were attacked by The Beast. Fundación Nueva Vida – an organization that gives prostheses to amputees, including migrants, with the help of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) – launched a program in Mexico and Honduras in the last decade and has assisted close to 1,300 migrants maimed by The Beast.

Walter Aguilar, a Honduran in his forties, makes prostheses for people whose American dream turned into a nightmare. Although not as a migrant, he also lost a leg at the age of 17 while working as a duck hunting guide for Americans. That day in the mountains the pick-up truck in which he was riding overturned, severing his leg.

“My leg was amputated in Nicaragua. Doctors were very kind to me and kept my hopes up. They told me a young man, an amputee, would come and teach me how to use the prosthesis. He showed me that life was not over yet and that I could lead a normal life,” Aguilar recalled.

After a long physical and emotional recovery, he is now a prosthetist.

Aguilar has a kind, good-natured demeanor and an impeccable haircut. He moves around his workshop with agility, hardly revealing his use of a prosthesis. There’s a large board on the wall where he hangs the tools with which he makes and repairs his patients’ prostheses.

On an October afternoon, five Hondurans are waiting in the small reception while Aguilar repairs their leg prostheses. The men, whose ages range from 20 to 50, converse about their journeys and how they lost their legs. “I didn’t get a good grip; I only held on with three fingers and since I was heftier back then, I lost my grasp. Then, I woke up in hospital without my leg,” one of them says.

Most of them, in good spirits, even made jokes about how unmerciful the road was, recalling anecdotes. Some of them said they are not going back, while others want to try again.

One of them said he has made the trip more than eight times and is waiting for Aguilar to repair his prosthesis to try again. “I made it to the U.S. in 2008 and 2012. I was working in Texas, but then I had the accident. Now that I got used to the prosthesis, it won’t take me long to be back on the road.”

IV. The Beast’s secret

The Beast has a secret very few people know about. This unstoppable, giant, metallic animal has a weakness. There’s a handle in the back of the last freight car that can stop the train. But doing so has a cost: Ferromex’s security guards will show up.

“On our way here, we took the train in Coatzacoalcos with the intention of getting off in Tierra Blanca. Halfway through the trip, we noticed the train started to slow down, and a group of young men were running toward us and yelling that we should get off. We thought that was the station, and migration officers were going to detain us. We got off the train and noticed that security guards were coming our way. They grabbed us, hit us, and put our necks on the rails. They said they would let the train cut our heads off. They forced us to the ground, which was hot, for about 30 minutes before letting us go,” said Javier, a Honduran who had hidden under the bridge in Irapuato in early October.

Although Ferromex’s armed security guards are responsible for overseeing the railways, criminal groups in fact control the routes. It could be a cartel, a gang, or a local group who robs migrants. They are extorted as The Beast travels at high speeds. Those who don’t pay run the risk of being thrown off the train, which has maimed and killed many.

There are no records of the people The Beast has killed or maimed. Undocumented migrants are usually buried alongside destitute Mexicans, rendering the actual numbers incalculable.

By 2005, railways extended up to Tapachula, on the Mexico-Guatemala border. Many migrants died there, and their remains were buried in the Jardín cemetery. Old-timer gravediggers told me: “The bodies were torn apart. We dragged them but their parts would often fall off. Dogs ate the feet or hands that fell from the carts since they were not brought in coffins and were already decomposing,” related Santos, a gravedigger who has buried migrants for more than 25 years.

For many years, The Beast’s victims came from Central America. However, U.S.-bound migration patterns changed in 2018. Not only Hondurans, Salvadorans, Guatemalans, Nicaraguans and Mexicans ride on trains but also Venezuelans, Ecuadorians, Haitians, and even migrants from other continents. In 2023, Mexico’s National Immigration Institute (INM), issued close to 100,000 temporary permits to migrants from 103 countries from all continents. Nowadays, it’s not improbable to find migrants from Africa or Asia.

V – The journey north continues

One month after having his left leg amputated, Pérez wrapped his stomp with a black, elastic bandage, made a knot on his pants and packed his belongings. Then he grabbed a pair of crutches and hobbled toward the train to ride on it again.

Standing next to the rails with a backpack on his shoulder, Pérez said goodbye to four dear friends who had given him shelter, food, medicine, and company in Irapuato during a month of convalescence. Before the train arrived, he had instructed his cousin and travel partner to get ready. He listened attentively to the train’s hoarse whistling, the hint that it was time to leave.

At that moment, his phone rings. His father is calling from Venezuela, more than 5,000 kilometers away, asking him to stop this madness. If he waits, together they will find a safer way to travel, his father promised him.

Although he’s not the kind of person who waits, they all convince him to stay, to go home and heal this sore stomp while they find another way.

A pastor and a group of people who had been watching him a few meters away rejoiced to see him walking back and took him to a temporary home downtown.

In October 2023, I met him in a small room in a suburb of Irapuato. He leaned out of the window facing the street to see who was knocking at the door.

He was surprised we were interested in his story and welcomed us with a smile.

“What was going through your mind when you were about to board the train again?” I asked him.

“Nothing. I just wanted to leave.”

Although the accident changed Pérez’s life, he has set his sights on reaching the U.S.

“What would you do if you had to come back?” I ask him. But that’s an option. He doesn’t even have a well-thought answer. That’s simply not a possibility.

Pérez is one of the thousands of migrants fleeing from violence, hunger, and dictatorships. “My dream is to travel the world and create content,” he says while showing us one of his videos dancing salsa in a small, white-painted room. He was an agile dancer; his face saddens as he watches the video.

But now, with one leg and against all odds, Pérez found a way of continuing his journey. Armando Gutiérrez, the pastor who helped him recover, found a place for him in a shelter in Ciudad Juárez, a city that borders the U.S.

Shortly before noon on November 3, 2023, the pastor picked him up. He packed some shorts, three shirts, extra pants, underwear, a speaker to listen to his favorite salsa songs, and a phone charger; light luggage for such a long trip.

Before getting in the car, he turns around one last time and says goodbye. He made a gesture of victory by slightly lifting his crutches. The car drove away, leaving a buzzing in the air. Pérez is now a small dot on the road that leads to the U.S. Always heading north, and never looking back. His gesture, rather than a farewell, seemed like a greeting to the road. The Beast had attacked him, but he kept walking.

VI. Epilogue

In early January 2024, Pérez sent me a message: “Happy new year. I’m in Tennessee.”

He wrote to me again a few days ago. “I’m working. Sometimes I drive a cab or sell candy on the streets. I’m getting by while I look for a good job and realize my dreams.”