In 2023, more than half a million undocumented migrants, most of whom came from Venezuela, crossed the border into Honduras – where many of them can save money and rest before continuing their journey to the U.S. Friends and families spend their days in improvised or illegal shelters remembering their experiences and planning for an uncertain future.

Text: Daniel Fonseca

Photography: Fernando Destephen

Jeremías carries a blue elephant, an orange F1 car and a toy shovel, which he received in a migrant shelter, on his backpack. He’s wearing a Spider-Man shirt and a Mickey Mouse cap. While his mother, Yosimary, asks for money to continue their journey north, he’s playing on the sidewalk next to the traffic light between the Third Avenue and 9th Street in Comayagüela, in Honduras’ Francisco Morazán department. When cars stop, Yosimary, who’s pregnant, hands out strawberry popsicles to drivers as a gesture of gratitude, hoping they give her some money.

A driver gives her food and drinks from Burger King. The traffic light turns green, and the vehicles accelerate. Another person gives her 11 lempiras (around $0.44) which fall to the ground, but she calmly picks them up. I like this country very much; Hondurans show solidarity for others, she says.

More than half a million undocumented migrants crossed the border into Honduras in 2023. These numbers, which had been rising since the end of the COVID-19 pandemic, almost tripled from 2022, according to the National Migration Institute (INM). Most migrants in transit through Honduras are Venezuelan, but citizens from other countries started migrating north over the last five years. The highest number of migrants come from Cuba, Haiti, Ecuador, Colombia, China, Guinea, Senegal, and India, and migration from other countries is increasing.

Children, in addition to their status as migrants, are particularly vulnerable. Between January and April of 2024, 35,617 children of various nationalities crossed the border into Honduras en route to the U.S., where most families will apply for asylum. Migrants are fleeing from poverty and violence in their countries but also on the road. Of those children, 16,863 are 10 years old or younger.

More restrictive immigration policies in Panama, such as expediting the transit of migrants, have turned Honduras into a stopover for many families as they need to save money or receive medical attention after crossing the Darien Gap.

When Jeremías is not accompanying his mother on the streets, he thinks about what he wants to do when they reach the U.S. He wants to be a police officer, to help his sister and grandmother in Venezuela get to the U.S. and learn things he doesn’t know yet.

“When I grow up, I’ll be an intelligent person,” he says.

When they are done for the day, Yosimary and other migrants get together to tell each other ghost stories. They are renting a room in a house owned by La Profe, a former university professor who provides migrants with accommodations. They sit around a gas stove, on which they cook food for 23 people, and talk about what they left behind in Venezuela, what they’ll do when they get closer to the U.S. border and when they cross it. But they mostly talk about the Darien jungle – a territory between Colombia and Panama controlled by organized crime – where human rights violations against migrants occur every day.

“At about 3 a.m., a Haitian man let out a terrifying scream, which was followed by a clap of thunder. I thought the hill we camped on was landsliding; it was a moment of despair. But the young Haitian had seen or was having a nightmare where he was being eaten by a giant snake. When he left the tent, he noticed marks on his body as if a snake had been wrapped around him,” Yosimary relates.

Jeremías is watching Masha and the Bear on a cellphone, and the other children are running around, but they are listening.

The other migrants share similar stories. They say a man once jumped off a cliff because the jungle had driven him to desperation: sightings that disappeared among the trees saying that they should not continue, tents with dead bodies, a crimson river that smelled like blood and the children’s efforts to keep their eyes closed, most of the time in vain. “I did what I could to prevent Jeremías from watching these things, but he heard what adults said, so I try to help him forget those images. If those experiences leave an impression on adults, can you imagine what they do to children? But seeing how days went by without getting to the other side of the jungle was the main cause of our desperation,” she said.

Yosimary left Venezuela in September 2023. She was an officer in the navy but abandoned without leave after her superiors refused to release her from duty. If she returns to the country, she’ll likely go to prison. Besides her job in the navy, she worked as a manicurist to earn an additional income. “Although I had two jobs, it was not enough to maintain a family; we lived paycheck to paycheck,” she says. Having two jobs, she spent less time with her children, so she decided to migrate. She doesn’t have any relatives in the U.S. but is hopeful that she’ll cross the border, find employment and earn enough money to reunite her family.

Her 12-year-old daughter stayed in Venezuela, and the father of the baby she’s expecting died of malaria, a preventable and curable disease, months ago.

La Profe’s house is in Tegucigalpa, Honduras’ capital. She has asked us not to disclose her name and address because “there are people who do not approve of what she does.” That is, renting rooms to migrants of different nationalities for 250 lempiras (about $10) a day. There are eight bedrooms in her house, where dozens of migrants have stayed while saving money before continuing their journey. Of the 23 persons staying in the shelter now, 13 are children under the age of 13.

“I never thought I would work helping migrants who seek a better life, but I think migration is a right. We help them not to make a profit but because we are aware of that right to seek a better life,” La Profe said.

In Tegucigalpa, migrants have found refuge in several places. Some of them have been made available by the citizens themselves who charge a small fee or none. Migrants have also occupied public spaces where they sleep to avoid spending the night in the open. During most of 2023, migrants in transit through Tegucigalpa stayed in the empty facilities of the Trans-450, an unfinished public work and a reminder of corruption in the Mayor’s Office that became a refuge for hundreds of people in transit who did not have a place to stay. However, in late 2023, the municipality decided to lock the facilities, and migrants who had made a camp there were moved to the border.

Those families had not saved enough money, and those who were receiving medical treatment were left without a place to sleep.

In addition to La Profe’s rooms for rent, clandestine shelters in abandoned buildings have emerged. Here, migrants stay a few days and save money for a ticket to Guatemala. A young woman, who wishes to remain anonymous, provides shelter to migrants in an unoccupied building owned by her family.

“I was saddened to see older women and children on the streets getting wet when it rained. So, I asked my father if they could stay in the building,” she says.

Around 500 people have stayed in her shelter in recent months; most of them travel with their families.

Migrants at this shelter say migration authorities have looked for the building on multiple occasions to evict them, but so far they haven’t been successful. Ten children and their families will have to look for another shelter in three days and make room for other migrants.

Although the Honduran government offers humanitarian assistance in border areas like Trojes or Danlí, migrants say that such assistance is practically nonexistent in other parts of the country. Most shelters are privately funded or receive support from international organizations. According to Red Cross’s app Red Safe, there are 15 official humanitarian assistance centers in Honduras, but there are many more shelters in churches and houses.

Those who have access to these centers, which have trained personnel and more resources, receive purchasing cards for supermarkets, menstrual and personal hygiene kits, food, toys and clothes. The Red Cross alone has been assisting about 200 people a week for months. There was a drop in the number of migrants seeking assistance recently; significantly less than in October of last year when three times as many migrants were seen, according to a report by health care providers. “We provide them with psychosocial support and sometimes follow up on cases of sexual abuse, violence, etc.,” explained Andrés Medrano, a doctor at the Red Cross.

However, they acknowledge that psychological support, especially in cases concerning children, is limited. Glenda Hernández, head of social development at the Red Cross, says, “We have to keep in mind that migrants in transit receive support for a very short period of time.”

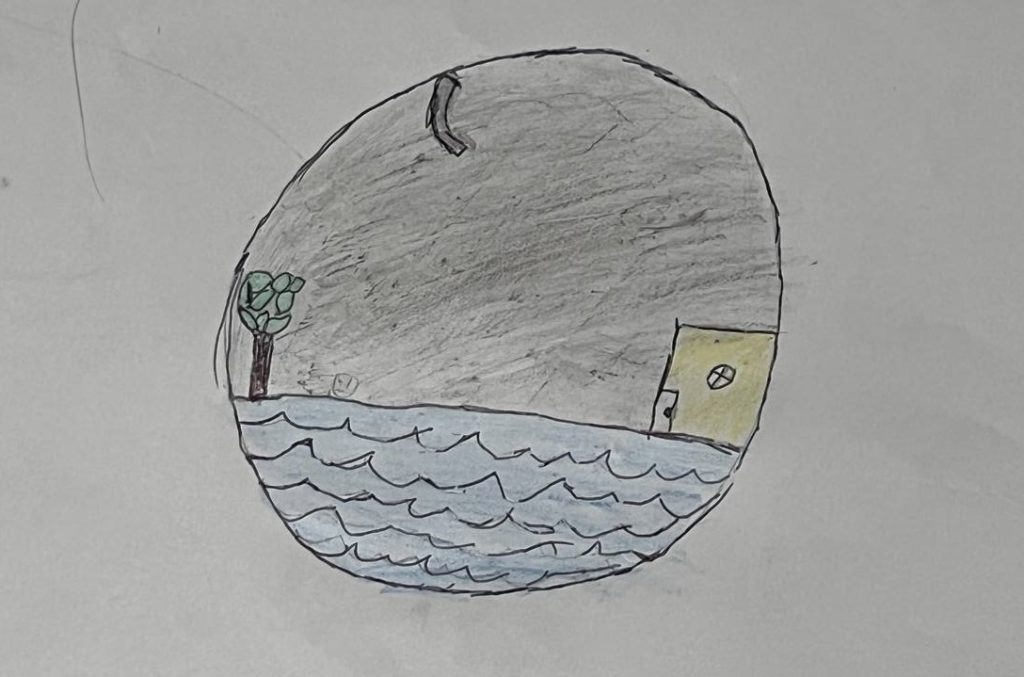

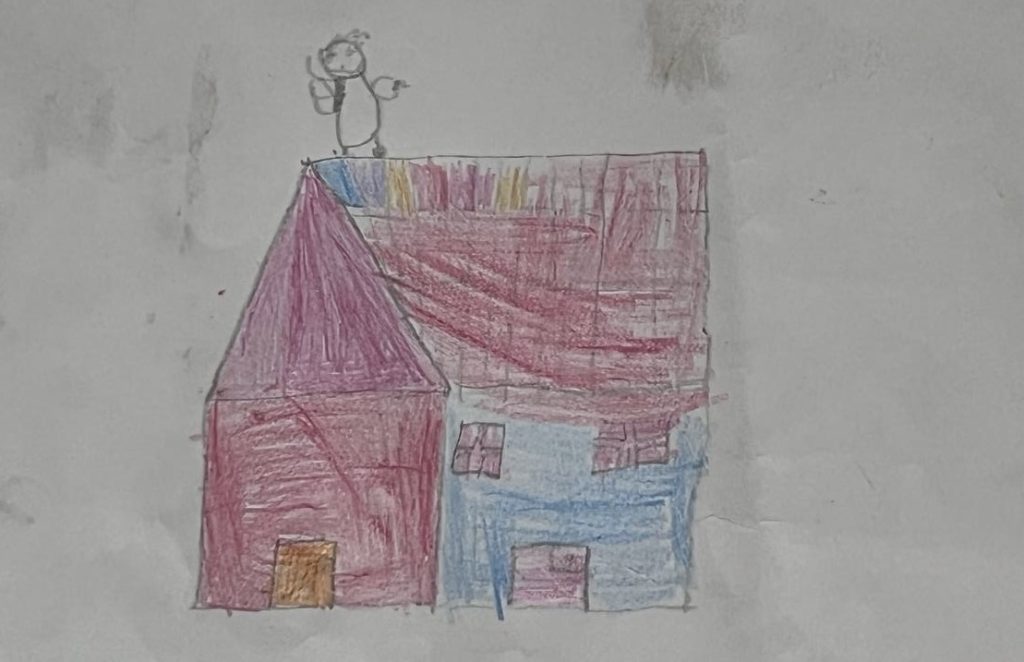

While adults can receive psychological support if they suffered abuse or trauma, children are usually treated with playful and pedagogical activities like drawing. “Providing psychological support to migrants in transit is complex because they want to get back on the road and in many cases don’t turn to organizations for help due to time constraints,” Hernández said.

It’s Sunday afternoon; they won’t go out to ask for money today.

In La Profe’s patio, there is a table tarnished by soot, five chairs, a gas stove, a sink to wash clothes and a sign with the names of the persons responsible for cleaning each day of the week. All the way to the end are the bedrooms, where migrants keep the few belongings they have procured so far. Children are playing, running around and drawing. They talk about their experiences up to this point, what they have left behind and what they’ll do once they arrive in the U.S.

Sebastian, 4, recalls the stars and the colors in Venezuela’s flag: yellow, blue and red. Bianca and Camila, 3, are twins who don’t remember anything. Patricia, 6, doesn’t either. Many children left their countries before having memories of a homeland and lived in other countries in the region – Colombia, Chile and Peru – before their families decided to migrate north to the U.S. Dahilyn, 13, remembers everything but misses the beach and the food, which in Honduras she finds too spicy.

Dahilyn (13): My mother simply said that we are going on a trip.

Yosimar (9): What did you feel when you were crossing the jungle?

Dahilyn: Nothing.

Yosimar: Well, when you crossed the river! The current was strong. What did you feel?

Dahilyn: Nothing. It was alright for me. The water was low, and the soil was dry when we crossed the river.

Yosimar: I crossed a mountain, but the ground wasn’t steady. I was crying, but a young lad, who is my father’s friend, grabbed me. I thought I was going to fall.

Dahilyn: Well, that’s how I crossed, by myself.

Yosimar: That’s because you’re a grown up; you’re an adult.

Dahilyn: I’m not an adult.

Since they met – in the Darien jungle, in a migrant camp in Panama or in Honduras’ south border – families staying in La Profe’s house treat each other like cousins. Older children protect, scold and fight with younger ones, who, even in a foreign country, find ways to get in trouble. Their caretakers – parents, uncles, older siblings – plan the route together: when is it less dangerous to go and how to stay together until they reach the border.

Yosimar: Honduras is nice; it’s better because I think there are schools where I can study.

Dahilyn: There are schools everywhere.

Yosimar: I want to study, read, write, and solve math problems when we get to the U.S. That’s what I want to do. When I grow up, God willing, I will become a doctor; my father will teach me how to be a doctor.

Dahilyn: Professors will teach you that. You finish high school and you get a diploma and then . . .

Their reasons for going to the U.S. are not very different. Darwin wants to go to school there and see the snow. Jeremías says there will be many children to play with.

Yosimary is not traveling with the rest of the group because of her pregnancy. She wants to get to the U.S. soon, but she has received obstetric treatment in Honduras because she experienced a discharge of amniotic fluid after crossing the jungle. Now, despite spending most of the day on her feet, she says her baby is healthy.

She hopes she’ll find work that allows her to spend time with her children once they arrive in the U.S. But for now, her concerns are similar to those she had in Venezuela: to get food, pay the rent, take care of Jeremías and find a biblical name for her baby, who will be born in a promised land.

I never thought I would go through a pregnancy in this situation. I never thought I would migrate and spend all day on the streets. I hope I’ll be in the U.S. by the time I give birth to my baby, but God has the last word.

She’ll leave the country in a few weeks, and someone else (another parent, another family) will take her place in the shelter, on the streets and under the traffic light between the Third Avenue and 9th Street in Comayagüela.

This story was covered as part of Cambiar la mirada. Nuevas narrativas sobre migración, a training program for journalists led by the United Nations Humans Rights Regional Office for Central America and the Caribbean, in collaboration with the Department of Media, Communication and Culture of Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and the Centre d’Estudis i Recerca en Migracions, and produced by Contracorriente.