A carbon offset project in Honduras’ La Moskitia has set off alarms among a faction of Miskito indigenous authorities, who claim that there was no prior consultation. This project, which has been promoted by the Spanish non-governmental organization Ayuda en Acción and designed by the Swiss company South Pole sparked concern at Verra, the U.S.-based certifying standards body that rejected its approval due to the absence of a consultation with local communities and doubts about the validity of data presented in its documents. This case underscores that while President Xiomara Castro promised to protect environmentally valuable areas by allowing Honduras to enter global carbon markets, some of these projects have been put in motion without consulting Indigenous peoples, who should be the main beneficiaries.

Text: María Celeste Maradiaga

Photography: Jorge Cabrera

Cover: Daniel Fonseca

Translation: José Rivera

Extensive cattle ranching, illegal logging and drug trafficking have threatened forests in Honduras’ eastern region of La Moskitia for over a decade. While the region is neglected and impoverished, it’s also one of the most biodiverse in Honduras and Central America. This is one of the reasons why politicians, companies and environmental organizations have shown interest in designing projects that seek to make a profit from natural resources while promoting environmental conservation.

They have been particularly interested in launching carbon offset projects that allow local communities, who protect ecosystems that are central to mitigating climate change, to sell carbon credits to global corporations trying to reduce their environmental footprint. On paper, it seems like a win-win scenario for companies and a region whose population is as diverse as its nature but lives in poverty.

Mirna Wood, an Indigenous leader in La Moskitia, first heard about this climate initiative 15 years ago in an event hosted by the cultural organization Ecos de la Moskitia as she helped decorate a ceremonial parade float in La Ceiba. A friend told her about carbon credit projects and explained how they work. Since then, she has been attentive to the development of these projects.

More than a decade later, in 2021, Wood—who is also vice president of a faction of Masta, a Miskito organization—was contacted by the developers of a carbon project in La Moskitia called Greentree and was asked by the leaders of the Bakinasta and Tawahka territorial councils to represent their communities during the consultation. That initiative never materialized, but Wood found out that there was a more developed and much larger project led by Ayuda en Acción and South Pole that leverages the absorption of carbon by mangroves – a concept known as blue carbon. She knew the project was well underway but suspected that communities had not been not properly consulted.

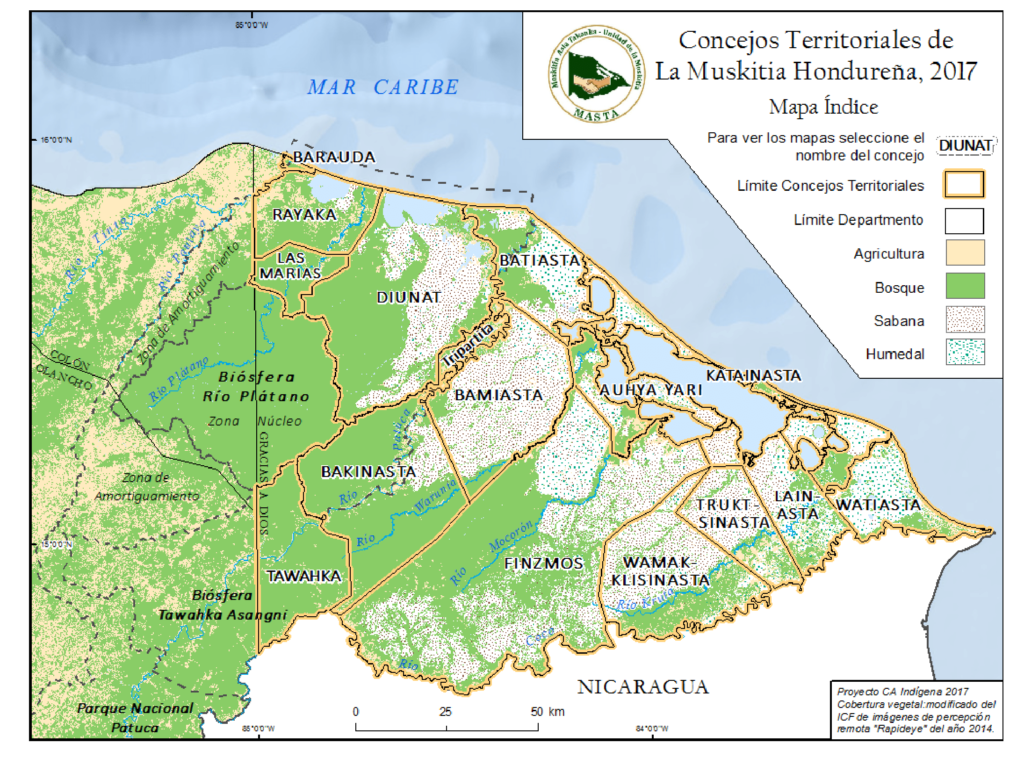

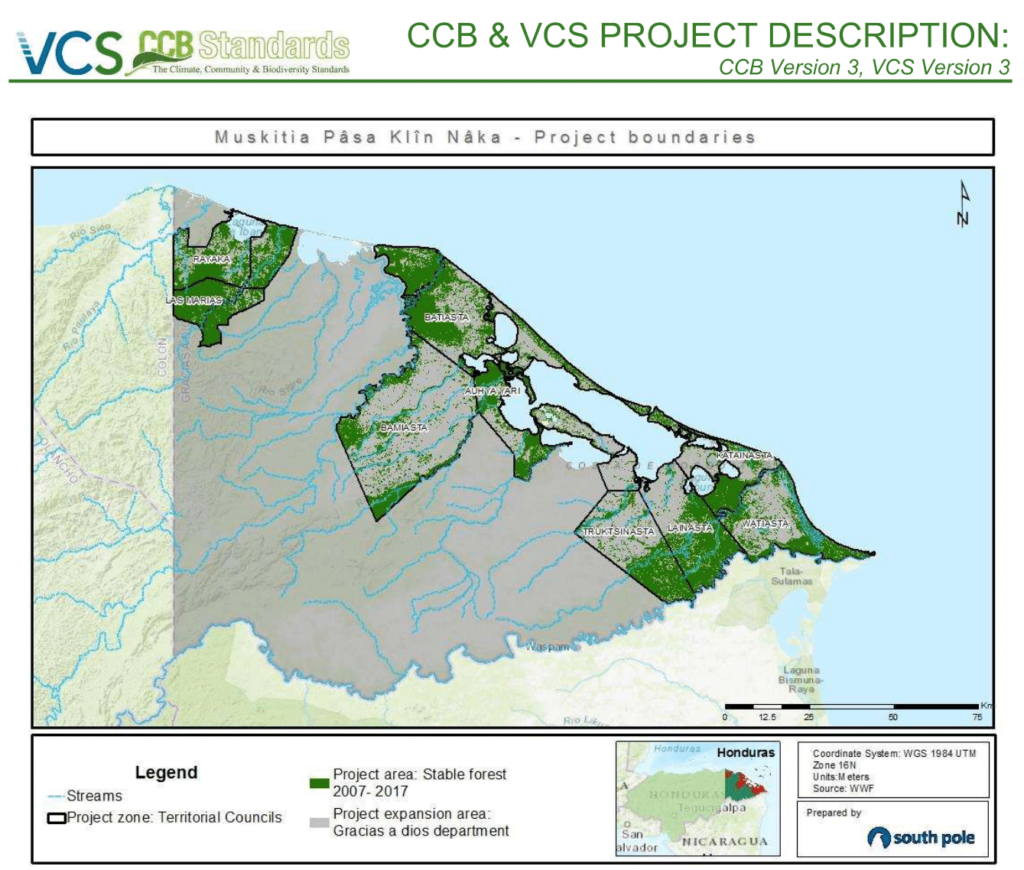

The project is called Muskitia Pâsa Klîn Nâka, which means “Muskitia, reservoir of pure air.” It seeks to reduce greenhouse gas emissions during a 30-year period by preserving mangrove, tropical and rainforests in 275,000 hectares spanning nine territorial councils in La Moskitia.

These nine territorial councils are part of the 15 that comprise La Moskitia in Honduras since 2012, when the State began granting land titles. According to ancestral land titles, the population and leaders of each territorial council hold complete authority over their territory. Although four Indigenous groups—Miskito, Pech, Tawahka and Garífuna—are settled in the region, the project covers land of the first two.

Greentree, the project whose developers contacted Wood, did not materialize in part because it was in conflict with the carbon project developed by Ayuda en Acción and South Pole. Wood said that communities within the project Muskitia Pâsa Klîn Nâka are not familiar with what it entails, and a free and informed consultation was not conducted; a requirement for any project developed in Indigenous territories in Honduras, as established by the International Labour Organisation’s 1989 Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention.

Wood told Contracorriente that she called Diego Iván Escobar, a Colombian employee of South Pole, to warn him that they needed the permission of Indigenous groups. After two calls, she said, Escobar stopped answering his phone.

Wood also contacted South Pole and Ayuda en Acción, but says they told her the matter would be settled between them and the leaders of the territorial councils and that Masta should not get involved. She filed a complaint with the Attorney General’s Office over possible irregularities in the process of consulting Indigenous groups in the region. The Attorney General’s Office confirmed, through its spokesperson Yulissa Gomez, that the complaint was admitted and that it initiated an audit into Ayuda en Acción, but that confidentiality bars it from providing further details.

This irregularity and others were underscored by Verra, the world’s largest certifier of carbon offset projects involving local communities (also known as Redd+), when they refused to proceed with the project’s registration. As a result, it placed the project certification on hold until its developers resolve possible flaws found in its design and development.

These are some of the journalistic findings made by Honduran news outlet Contracorriente as part of the Opaque Carbon investigation, led by the Latino American Center for Investigative Journalism (CLIP) and bringing together 14 media outlets from eight countries to probe how the carbon market is functioning in Latin America.

A project that promises progress for La Moskitia

The project Muskitia Pâsa Klîn Nâka is presented as a way out of the rampant deforestation and the difficulties that the Indigenous Miskito and Pech peoples in the nine territorial councils face. Unemployment is high, the health care system precarious and education deficient. In addition, illegal logging and wildlife trafficking are widespread.

“In the long term, the project is expected to make significant progress in the conservation and sustainable management of mangrove, broadleaf, and coniferous natural forests by means of strengthening local governance, maintaining the sustainable traditional community practices, protecting the indigenous culture, and achieving the economic empowerment of vulnerable groups,” the document presented to Verra reads. The initiative seeks to avoid the liberation of 399,286 tonnes of greenhouse gasses during the first 10 years.

Ayuda en Acción, one of the organizations behind the project, has been operating in Honduras for more than 20 years, including 11 in La Moskitia. This NGO and its director in Honduras, Roberto Buzzi, are not only known for signing treaties for the protection of Indigenous children and strengthening fishery and livestock husbandry under other administrations, but also for their involvement in forums to promote employment programs for Indigenous groups working in the cocoa and fishing production chains.

According to the project’s design, it will be conducted in two phases. An initial one will take place in seven Miskito territorial councils: Lainasta, Katainasta, Watiasta, Ahuya Yari, Truktsinasta, Bamiasta and Batiasta, which constitute 214,934 hectares suitable for carbon capture. The second phase will include Rayaka, a Miskito territorial council, and Las Marías, a Pech territorial council, for an additional 56,594 hectares. After the second phase, developers expect to expand the project throughout Gracias a Dios, in other words, in the entire region of La Moskitia.

Contracorriente found two documents that Ayuda en Acción presented as proof that Indigenous groups were consulted about the project. The Project Design Document (PDD) doesn’t specify the number of people who were consulted and only includes a timeline of meetings with council leaders, State authorities and Indigenous organizations from the region between December 2018 and March 2022.

According to the extended version of the Project Design Document, communities signed a cooperation agreement “to formalize their participation in the project” in June 2021. Ayuda en Acción has stated on several occasions that they have met with communities to discuss the project. For instance, its climate change coordinator, María José Bonilla, talked on a live television broadcast about a “demanding construction process to communicate and meet with communities and the rest of the population in La Moskitia”. Bonilla’s name appears on the report as the project proponent’s contact person.

Contracorriente contacted Bonilla to inquire about the consultation of the carbon offset project in La Moskitia and the socialization workshops organized by Ayuda en Acción. Despite attempts to reach her by phone and WhatsApp since February of this year, Bonilla had not responded to our inquiry by the time this investigation concluded.

Contracorriente then asked Lizzeth Ordóñez, communications officer at Ayuda en Acción, about Verra’s refusal to certify the carbon project. She did not respond to our interview request but wrote in an email that the project “was collectively built with communities,” and that “an inclusive dialogue and process of socialization took place.” She also said that programs carried out by Ayuda en Acción had no connection to the carbon project, as suggested by the PDD and warned by Verra in its letter. On the status of the initiative, she only said that “the project is suspended.”

Continuamos en Honduras los talleres por las comunidades para dar a conocer la 'Iniciativa Carbono Azul y otros ecosistemas', que desarrollamos junto a @southpoleglobal.

— Ayuda en Acción (@ayudaenaccion) July 5, 2021

Si quieres saber más del proyecto 👉🏽 https://t.co/rLmevjzNgm pic.twitter.com/QJm2un5sdE

”Socialization workshop to inform communities of ‘The Carbon Blue Initiative and other ecosystems’ developed alongside @southpoleglobal continue in Honduras,” Ayuda en Acción posted on X.

Víctor Padilla, project evaluation and monitoring manager at Ayuda en Accion, assured Contracorriente that a consultation process with territorial council leaders has been taking place since 2017, and that disagreements among Miskito leadership are the reason why the project hasn’t been launched yet, not faults in the consultation. “Since 2017, we’ve participated in consultations with leaders who are highly regarded in their communities. The other faction of Masta’s board of directors did not participate in consultations for the project since we didn’t know all of them at the time, and they are spreading false information on social media and have already filed a complaint,” Padilla said during an interview at Ayuda en Acción’s office in Puerto Lempira, Gracias a Dios, in December 2023.

Padilla says that leaders of the territorial councils were consulted, and that it’s their responsibility to inform communities in La Moskitia, not the project proponent’s.

“The project has been thoroughly analyzed, and we’ve encouraged the participation of territorial council leaders. Territorial councils represent communities, who own the territory, so leaders should have a clear understanding of the project. It’s reasonable that they inform the communities they represent. And if there are conflicts with authorities at higher levels, that’s going to be a significant problem,” Padilla argues.

South Pole, a prominent company in the global carbon market, is mentioned as a consultant in the Project Design Document. The project was validated by the Instituto Colombiano de Normas Técnicas (Icontec), a Colombian auditing body. It was then presented to Verra, which leads one of the most widely utilized certification standards of carbon offset projects in the world, for its approval to then sell carbon credits in the market. But this is where the process stopped.

Verra’s doubts

Verra issued a letter denying registration of the project in La Moskitia in July 2023. They argued, among other things, that “the project description and the monitoring report contain incorrect and incomplete information.” As a result, “the VCS project status on the Registry has been updated to On hold”. Verra’s decision to deny Ayuda en Acción registration under its Verified Carbon Standards (VCS) program and another one named Climate, Community and Biodiversity Standards (CCB) means that the project cannot sell carbon credits on the market yet.

In the letter, which had not been posted on Verra’s website until we requested access to it, the company outlined its doubts and concerns. Verra coincided with Wood and warned that “the project proponent has not presented any information regarding consultations occurring before the implementation of the project activities” and that it “has not demonstrated that consent was obtained from communities prior to the implementation of project activities that impacted their rights.”

Verra doubted that meetings between Ayuda en Acción and communities had the outcome that the proponent claims. “These meetings are described as meetings with community leaders and local authorities to discuss the benefits and next steps of the project in the territory”, warned Ciara McCarthy, Verra’s director of natural climate solutions, on the letter which was uploaded to the certifying standard’s registry on February 2 of this year, but that “this does not indicate that these meetings were a forum to obtain free, prior, and informed consent.”

According to Verra, there is also a contradiction in the fact that Ayuda en Acción requested 17 June 2017 as the selected project start date, but initial meetings with communities would have taken place in December 2018. That is, 18 months after the project start date. While it’s common that carbon offset project proponents request retroactive starting dates, they should demonstrate that they have been working with communities since then.

Verra also pointed out several inconsistencies or inaccuracies in the PDD’s forestry data, including that it did not apply the spatialisation model to calculate a baseline of emissions in the project area; that it did not follow the methodological guidelines for outlining the reference area against which deforestation dynamics would be compared; and that it did not provide appropriate sources for analyzing historical deforestation there.

Moreover, Verra questioned the lack of a clear distinction between the carbon project and Prawanka, a program promoted by Ayuda en Acción which supports employment by means of fishing and cultivating staple grains. They explained that Ayuda en Acción requested a start date for the carbon project at the same time the Prawanka program was launched even though the report stated that “the Prawanka program does not appear to include the usage of carbon finance among its objectives.” As a result, it stated, “it is unclear if the project requires carbon finance to be developed.” This issue calls another important requirement of any carbon offset project into question: additionality, in other words, proving that the conservation outcomes would not occur without the existence of carbon credits.

Despite Verra’s refusal to register the project, their methodology gives Ayuda en Acción the opportunity to make the necessary corrections and send another request to register the project by July 4 at the latest.

Verra not only addressed the letter to María José Bonilla but also to Martha Ivan Corredor, representative of Icontec who audited the project.

This journalistic alliance was not able to verify if Icontec endorsed Ayuda en Acción’s claims regarding consultations in La Moskitia since their audit report was not publicly available on Verra`s website as of March 2024.

Icontec refused to send a copy of the audit report. “The report is not complete because the audit is on hold. Information about the project was made available to the public on Verra’s website,” wrote Laura María García, a specialist in validation and verification of forests at Icontec.

Regarding the verification of a prior consultation, Icontec said that “the audit team conducted a validation and verification process in accordance with current legal provisions” and that “it complied with the regulations that apply to the Moskitia region.” It did not provide details of said legal provisions. “Authorities and representatives of communities were interviewed,” they added without mentioning any names.

Finally, regarding the flaws detailed by Verra in its letter rejecting the carbon project, Icontec said that “findings were identified and will be reported and made public once the requirements of the standard are met.”

La empresa ICONTEC, acreditados bajo la ISO 14065, está realizando auditoria para verificar y validar el proyecto REDD+ Muskitia ba Pâsa Klîn Nâka sa de 7️⃣ Concejos Territoriales y un Concejo de tribu PECH.

— Ayuda en Acción (@ayudaenaccion) August 11, 2022

Esta iniciativa la facilitamos junto a @SouthPoleglobal. pic.twitter.com/BIEVif0yRs

A conflict within Masta

In addition to alerting communities, Mirna Wood filed a complaint against the project promoters, Ayuda en Acción and its representative, Roberto Buzzi, before the Special Prosecutor’s Office for the Protection of Ethnic Groups and Cultural Heritage within the Attorney General’s Office, for allegedly infringing on Indigenous peoples’ right to a free, prior and informed consultation.

The complaint was filed in July 2023 and demanded an investigation into the finances and assets of Ayuda en Acción and South Pole, including an inquiry into the possible embezzlement of funds destined for social projects.

The faction of Masta that Wood leads also filed a complaint against Norvin Goff, former president of the organization, for allegedly accepting the carbon offset project as well as signing an oil concession in the Miskito Cays and other projects on behalf of the Miskito people and in partnership with other leaders. They allegedly carried out these actions without informing and consulting the majority of the Miskito people and local communities they are supposed to represent.

The other Masta faction, of which Goff is a member, says that the people who have filed complaints against the project endorse the invasion of cattle ranchers from the department of Olancho. Goff’s faction accuses them of allegedly refusing a Miskito land reclamation process by advocating for the construction of a road that could cut through the Río Plátano Biosphere Reserve’s core zone.

This division within Masta, and also among the leaders of the different territorial councils revealed by the carbon project, has affected communities in the region since the land titling process in 2012 and has grown amidst state neglect and clientelistic negotiations.

The faction to which Goff belongs is led by Elvis Greham, who signed a letter of understanding to conduct studies related to the carbon project alongside Ayuda en Acción and South Pole in 2021.

Unlike Ayuda en Acción’s claim that a consultation took place between 2018 and 2022, Greham maintains that Masta, Ayuda en Acción, and South Pole signed a letter of understanding in 2021, but that a prior, free and informed consultation required to set it in motion has not been conducted yet. He also said that not much is known about carbon offsetting in La Moskitia.

“Eight hundred people were informed and consulted in eight territories. While individuals who have been involved in the process understand what the project is about, most people don’t. But some leaders are working to inform their councils,” Greham explained.

Greham says he was contacted by Ayuda en Acción and South Pole in 2021, and they asked him to endorse the carbon project. As president of Masta, he called for a meeting with the eight Miskito territorial councils, not including the Pech people, involved in the project. Members of communities were asked if they would like to be a part of it.

The problem is that 800 people were asked about the project, but 158,400 people live in 267 communities in the 15 territorial councils of La Moskitia, according to the National Statistics Institute (INE) and Masta. The Lainasta, Katainasta and Truktsinasta councils, which are part of the project, have a population of more than 20,000 inhabitants each. The Bakinasta and Batiasta councils, which are adjacent to the Río Plátano Reserve Biosphere, each have a population of 4,000 to 10,000 inhabitants.

Greham said that this preliminary consultation was just an “initiative” and should not be considered a prior, free and informed consultation. “We signed a letter of understanding, and if any party doesn’t feel comfortable and wishes to withdraw from the project, they’re allowed to. We are in the consultation stage and haven’t made more progress because of obstacles set by the government,” Greham pointed out. He’s referring to a moratorium issued by the Castro administration in June 2022 which puts all carbon offset projects in the country on hold until the Secretariat of Natural Resources (SERNA) and the Forest Conservation Institute (ICF) determine the forest carbon inventory anew.

“Perhaps they [Ayuda en Acción] considered that preliminary consultation an all-inclusive one. But we disagree. This is why we decided to amend Masta’s statute in August 2023 and added a provision, establishing that a consultation to the majority of the population should precede any initiatives,” Greham added.

Despite dialogues between both Masta factions, Greham says that the lack of information, land grabbing, political interests and conflicts in the process of land restitution have led to disagreements about governance among leaders in La Moskitia.

“I’m not in favor nor against the complaint [filed by Wood]. I was appointed president to look after the well being of my people, and I think we should conduct a proper consultation. The letter of understanding is not binding, and we want to make informed decisions in the interest of the population,” Greham said.

He promised to send us a copy of the letter of understanding that he and the project promoters signed in 2021. But he has not responded to any of our calls and messages since January 2024.

Yulissa Gómez from the Attorney General’s Office confirmed that the complaint made by the Masta sector to which Mirna Wood belongs was received by the Ethnic Prosecutor’s Office, which is currently working together with other prosecutors to carry out the corresponding audits of the Ayuda en Acción organization. Gómez did not give any further information on the case, stating that it should be kept confidential so as not to hinder the investigations.

Possible irregularities in the consultation

Tea mangrove trees or “laulu” in Miskito have an imposing presence around the Caratasca lagoon, also known as the “crocodile lagoon.” The trees attract seagulls and herons while fish flutter close to their roots. Locals arrive in canoes to catch shrimp, common snook, tilapia, and sea bass and to cut firewood. Caratasca is connected to smaller lagoons such as Tansin, Warunta and Tilbaca, forming the largest lagoon system in Mesoamerica.

At the other side of the lagoon away from Puerto Lempira is the Kaukira community, which is part of the Katainasta territorial council, one of several involved in the carbon project.

In Katainasta, land is mostly used for agriculture, hunting, cattle raising, and trees are harvested to build canoes and to sell lumber. On the Caribbean coast, fishermen catch sea cucumbers and jellyfish to then export them to China, while others leave on fishing boats for weeks to catch lobster, crab and shrimp. They risk their lives due to the inherent dangers of underwater fishing.

Few people know about the carbon project in this community. We asked elders on the beach, young men who drive motorcycles and women who sell products at the market, but of about eight people we talked to, no one knew about the carbon project or if it would benefit communities, which have managed public goods for years. They didn’t know about carbon offsetting either.

Joaquina Calderón, forest development coordinator at ICF in La Moskitia, said that communities in the region don’t know much about carbon markets, and that ICF, a government institution responsible for managing forests, was never consulted by Ayuda en Acción and South Pole about launching the project.

Guillermo Rosales, Christian pastor and member of Katainasta’s board of directors, is one of the individuals who accepted the project, but when he was consulted, it was limited to mangrove carbon sequestration and had not extended to other ecosystems and territorial councils in La Moskitia. “Territorial councils are always observant of what’s going on. If South Pole and Ayuda en Acción come back, we’re willing to negotiate conditions that benefit communities. When they were here, they talked about incentives worth millions for offsetting tonnes of carbon,” he explained.

The rampant deforestation that threatens La Moskitia is the reason why some individuals accepted the project in the Katainasta territorial council.

In 2023 alone, ICF documented 868 deforestation warnings in La Moskitia as well as 1,276 warnings in the Río Plátano Biosphere Reserve. In total, 5,869 hectares are under threat of deforestation in La Moskitia. Sixty-six percent of all deforestation warnings in Honduras were registered in this region in 2023.

The Prawanka mystery

Another aspect of the Muskitia Pâsa Klîn Nâka project that concerned Verra is its incorporation to three programs conducted by Ayuda en Acción that have no connection to carbon offsetting.

Prawanka is one of those programs; it’s financed by Switzerland and implemented by the Lutheran World Relief and the Mennonite Social Action Committee (CASM). The goal is to increase the income of communities in La Moskitia by supporting fishery and the production of rice, beans and cacao.

According to Ayuda en Acción’s website, a total of €24 million were destined for Prawanka between 2017 and 2024. During the administrations of both former President Juan Orlando Hernández and his successor, Xiomara Castro, Prawanka signed agreements with public institutions to promote the production of staple grains. One of those agreements was signed with the Secretariat of Agriculture and Livestock (SAG) in November 2022 “to benefit 8,000 fishermen” and another one with Senprende, a government institution that supports small and medium businesses, in August 2023.

This is the program that Verra questioned for not having any connection to the carbon project’s goals.

This seems to be the case with two other programs, Afro and Indigenous Peoples of Honduras (PIAH) and Yamni Iwanka, which also promote community development in several territorial councils in La Moskitia. The former is financed by the European Union and the latter by the Japanese government. These two programs are mentioned, alongside Prawanka, in the Project Design Document.

Although there’s no detailed connection between the three programs and the carbon offset project, and communities in La Moskitia are not aware of any, Ayuda en Acción has posted about a connection on social media. They described Yamni Iwanka as a project “that helps reverse global warming by nourishing the soil, allowing a higher offsetting of carbon.”

🌽Las familias tendrán ahora su propia granja avícola y las aves contribuirán a nutrir el suelo para que capture más carbono y así revertir el calentamiento global 🌍

— Ayuda en Acción (@ayudaenaccion) October 17, 2023

🤩Esta iniciativa la hacemos con el proyecto #YamniIwanka junto al @BancoMundialLAC y el Fondo Japonés 🙏🏽 pic.twitter.com/I16C2MY418

Victor Padilla, employee at Ayuda en Acción, told Contracorriente that none of these three programs promoted by the company are related to the carbon offset project in La Moskitia even though they are mentioned in the Project Design Document. “Not all projects carried out by Ayuda en Acción in La Moskitia are related to the Muskitia Pâsa Klîn Nâka project,” he added.

South Pole backs down

After Verra published the letter suspending the project’s certification, apparently one of the promoters changed their mind about the project.

Since mid 2021, South Pole has had a page dedicated to this project on their website, describing it as the source of “sustainable income opportunities that don’t depend on the forest being cut down” that brings about “a myriad of benefits. To address deforestation and protect Muskitia’s breathtaking landscapes the project is collaborating with 8 Indigenous and Afro-Honduran communities. Governance structures are strengthened and communal visions for the future are jointly developed with local councils, increasing participation and creating the foundation for long-term, shared prosperity,” the page read. On their social media accounts, they also published images of jaguars in the project area from camera traps and aerial shots of the Caribbean coast as well as a help request in the aftermath of hurricanes Eta and Iota, which caused destruction in communities.

That project presentation, however, was taken off their website sometime after November 2023, according to Internet Wayback Machine, suggesting that South Pole no longer wishes to exhibit the project in their portfolio.

Upon receiving an inquiry from Contracorriente, South Pole said that they are evaluating their participation in the project, although their doubts are not due to concerns expressed by Verra but to the decisions made by the Honduran government. “While we believe the Muskitia project is very important, the new legislation for the forest carbon market in Honduras creates a risk that hinders foreign investment in the future. Despite our significant equity investment in this project to date, we are reviewing our role and involvement in the future,” a spokesperson said via email. “We would like greater clarity and certainty on how forest carbon credits will be regulated as well as a clear timeline for when the pending regulation will be published and enacted.”

When asked about the exact amount of capital invested in the project, they reiterated the above-mentioned statements and stressed that they have no further comments. There was no comment regarding Verra’s concerns about the project.

Apart from the Castro administration’s policy on carbon markets, South Pole turned down an interview to discuss the project in La Moskitia. “Our work has entailed broad consultations to all parties involved since 2018, including close to 100 meetings and the participation of around 4,000 members who belong to 180 communities. But the project is still in the development phase,” the company responded via email.

A new carbon law promoted without consulting Indigenous peoples

In her speech at the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP28) in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, in December 2023, President Castro offered to mitigate the effects of climate change by leveraging carbon sequestration.

“As a representative of peoples in the global south who were colonized for their natural resources, we face the worst consequence of climate change while the wealthy talk about space travel to escape to other planets, leaving behind a devastated Earth,” President Castro said.

Although Castro promised to hold the largest polluters accountable, and actor Leonardo Di Caprio praised her commitment, stating that Indigenous peoples in La Moskitia would benefit, the Honduran government passed a law to join the global carbon market without consulting the people she claims she wants to protect.

This is her second executive action concerning carbon markets since she took office in January 2022. In June of the same year, SERNA and ICF declared a nationwide moratorium on the sale of forest carbon credits “to reduce potential risks and social, environmental and economic problems” associated with the illegal sale of carbon credits in private projects. According to the communiqué, the goal is to “avoid the carbon trading colonization of our forests.”

In July 2023, shortly before Verra refused to register the project promoted by Ayuda en Acción in La Moskitia, Honduras’ National Congress passed the “Special law for the sale of forest carbon credits for climate justice.” This bill aims at joining the regulated global carbon market, establishing modes of carbon transactions in the country that include a “debt for nature and carbon exchange” based on environmental results which would reduce Honduras’ foreign debt.

Elsser Brown, director of the Development Agency of La Moskitia (MOPAWI), said that Indigenous peoples in the region were not consulted prior to the special law’s enactment and this reflects the absence of Indigenous peoples’ participation in state affairs. “There was no plenary and effective participation of Indigenous peoples, and while I don’t want to say there’s discrimination, this law has no regard for their rights,” he told Contracorriente.

The Honduran government promoted the special law as a way of rewarding people who have protected the forests for years and as a mechanism of climate justice that holds the largest polluters accountable. “In this part of the country, 45 percent of protected areas are close to Indigenous territories. And we should support them because they have protected the forests, rivers and mountains for decades,” SERNA Secretary Lucky Medina said on a television broadcast.

Some of the most known Indigenous leaders reacted negatively to the climate justice narrative pushed by the Honduran government. “Indigenous peoples have lived in these territories for centuries, and I think it’s nefarious to trample on their right to a consultation in the name of environmentalism,” said Miriam Miranda, Garífuna leader of the Black Fraternal Organization of Honduras (OFRANEH).

Malcolm Stufkens, deputy minister at SERNA, told Contracorriente it was necessary to swiftly approve the special law in order to obstruct irregular projects within the voluntary carbon market and this is why socialization among the Indigenous population did not take place. The deputy minister added that the indigenous peoples will be considered at the stage of drafting the regulations for the implementation of the law.

He also said that under the voluntary carbon market “the country was being distributed to several companies,” and the State decided to step in and protect public goods. “The previous administration didn’t recognize land ownership and didn’t ensure the participation of Indigenous groups, but we’re doing things differently,” Stufkens said.

By nightfall, as rain threatened to bring heavy swells in the Caratasca lagoon, Seldita Pedro, a Miskito woman and vice president of Bamiasta’s board of directors, was looking at the pier when she told us about their predicament: La Moskitia is up against a multi-headed monster that overpowers communities and threatens to strip people of their land.

The Bamiasta territorial council decided to abandon negotiations concerning the carbon offset project in La Moskitia due to lack of transparency in the process and fear of losing the use of their own land. “Nowadays, our territory is being invaded, and we’re facing territorial governance issues. We can’t overcome all of this on our own. Invaders extract colored timber and other natural resources and traffic endangered species as our fauna dies off. We feel defenseless in this fight against outsiders,” Seldita Pedro said, referring to invaders who extract their resources.

Initiatives promoted by the government seem to benefit outsiders, and there’s serious concern about the legitimacy of consultations and campaigns to inform the population.

In May 2022, Spanish singer Alejandro Sanz said he would allocate funds for Ayuda en Acción and the conservation of mangrove forests in La Moskitia. By selling two limited edition stainless steel bottles that the Spanish company Quokka manufactured, Sanz promised to preserve and reforest 250,000 hectares of mangrove forest by means of carbon offsetting.

“I won’t tell other people what to do, but I’ll tell you what I’m going to do: I want to reduce my environmental footprint as much as possible,” Sanz said at the COP25 in December 2019.

Elvis Greham knows who Sanz is and has heard his songs, but he didn’t know of the singer’s involvement in the same carbon project that he’s been a part of. “I had no idea,” he said.

Or, as Sanz sings in “When Nobody Sees Me”, “there are things that are very much yours that I don’t understand.”

Opaque Carbon is a project on how the carbon market is working in Latin America, in partnership with Agência Pública, Infoamazonia, Mongabay Brasil y Sumaúma (Brazil), Rutas del Conflicto and Mutante (Colombia), La Barra Espaciadora (Ecuador), Prensa Comunitaria (Guatemala), Contracorriente (Honduras), El Surtidor (Paraguay), La Mula (Perú) and Mongabay Latam, led by the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (CLIP). Legal review: El Veinte. Logo design: La Fábrica Memética.