Text and photography: Fernando Destephen

Translation: José Rivera

It’s been over 44 years since the disappearance, torture and murder of hundreds of people in Honduras, and Berta Oliva, coordinator of the Committee of Families of Disappeared and Detainees in Honduras (COFADEH), doesn’t feel like crying anymore because her main objective is to “contribute, serve and help.” She’s focused on creating awareness about the disappearances that took place in the 1980s and wants to preserve the historical memory so that the violence of a silent war against ideas doesn’t occur again. For that reason, she established the Museo Contra el Olvido.

According to COFADEH, at least 184 people were kidnapped, tortured and disappeared during the 1980s and 1990s. Those crimes took place during the administration of the Military Junta led by Policarpo Paz García (1978 – 1980 – 1982), following the doctrine of State national security under the guise of a civil government.

The Museo Contra el Olvido, an initiative by COFADEH, is not open to the public yet and goes back many years. The idea was born in the 1980s, when a place called Aldea Bonita in Valle de Amarateca was mapped with data obtained from the testimony of survivors of torture and statements from three 3-16 Intelligence Squad agents. There, a country house with a normal appearance was found, but the main house’s design had certain specifications. There are no rooms and there’s a wooden door with glass on the front and another door in the back that leads to a garage. According to investigations by COFADEH, victims were brought to the garage and then forced into the torture chambers.

Outside this house of torture, there was an area for grilling; it was the perfect way to convey the appearance of a normal country house. A few meters away stood a small structure made of red bricks with a water tank on top, but it didn’t contain a water system. The metal warmed up and turned into an oven. It’s a seven-block property where people were tortured and murdered.

Victims were taken to this clandestine location to make them feel fear, anxiety and isolation from the rest of the world. Many survivors only remember a chimney, a window and the cries of pain.

A health facility was built for the treatment and recovery of Nicaraguan and Salvadoran counter revolutionaries who had been injured in confrontations with guerrilla groups in the Honduran border. From the outside, the facility looked like a foster home (Aldea Infantil SOS), but it was in fact operating as an incognito hospital, where victims were expected to recover for further interrogations.

The seven-block property in the community of Aldea Bonita, previously owned by Colonel José Amílcar Zelaya Rodríguez, was bought by Mario Rivera López in 1976. The property became a clandestine cemetery and due to its proximity to a river called Río del Hombre the blood, odors and the remains of victims and part of the truth were washed away. Two structures stood in the country house, the foreman’s house, which was used as a jail to keep victims, and the main house, where they were sent to be tortured.

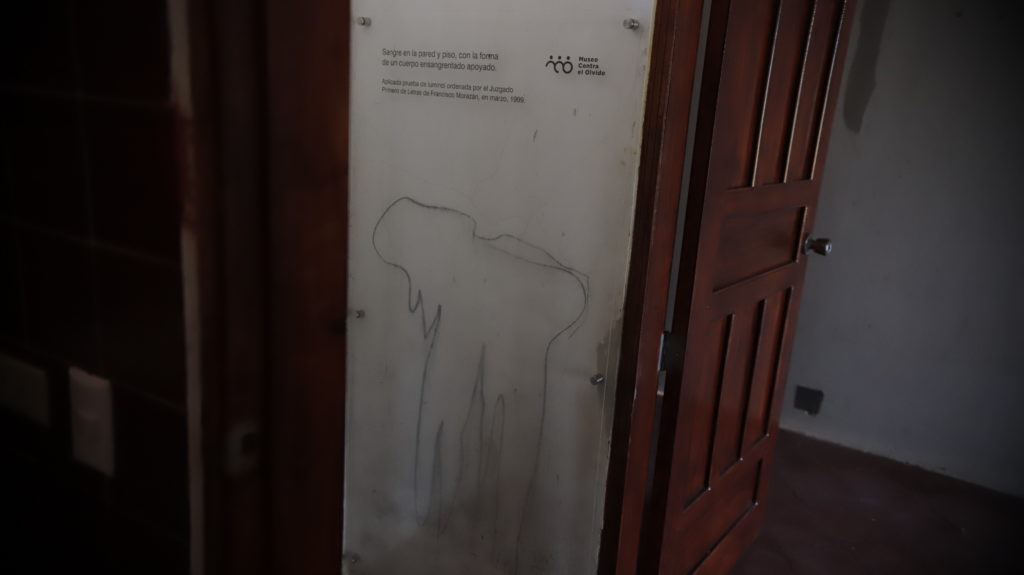

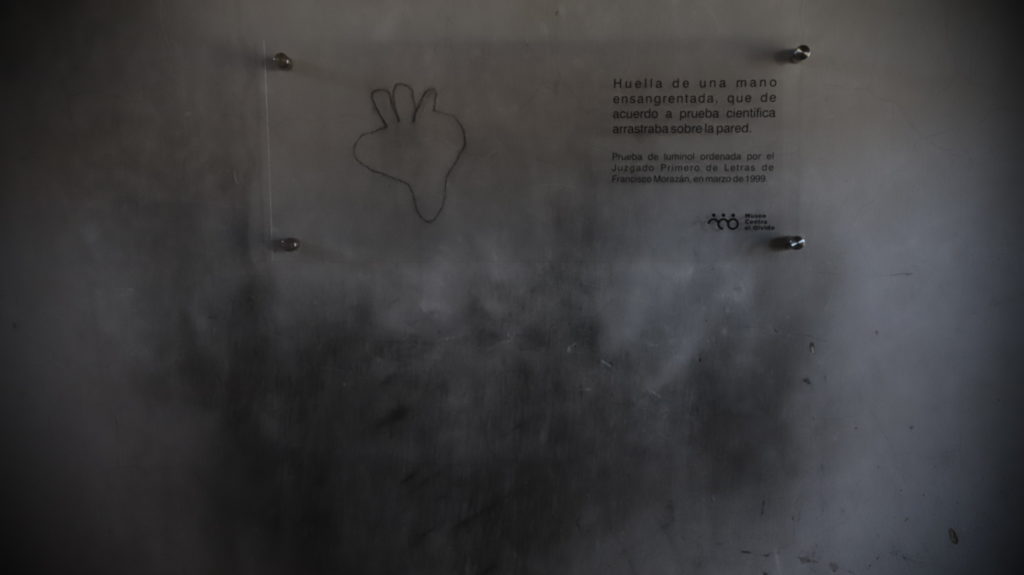

The main house evokes a dismal and gloomy feeling. Luminol uncovered handprints and traces of bodies in the walls enclosed by glass and the legend of what happened there: punishment, beatings and deaths. The silence reaches every corner of the house; a speechless witness that hides truths as gruesome as the skinning of people. According to COFADEH, there were two fires in the houses, one in 2009 and the other one in 2018, since the process to establish the museum began.

COFADEH located the house in 1987 and requested an intervention by the government in the 1990s. That’s how the process to acquire the property began, which continued until the administration of Manuel Zelaya Rosales (2006-2009).

The Inter-American Commission of Human Rights (IACHR) issued a ruling against the Honduran State in an emblematic case regarding the kidnapping and torture of six students, “Guillermo López Lone et al. vs. Honduras”. Milton Jiménez Puerto, a survivor who was kidnapped and tortured, was chancellor of Honduras in 2009, which contributed to promoting the museum. The coup against Zelaya in June 2009 and the three subsequent administrations of the National Party (2010 – 2022) delayed the project significantly, but it continued despite the obstacles.

The Museo Contra el Olvido is a way to recover the historical memory in the same way as the Location to Prevent Forgetfulness in Santa Ana, in the department of Francisco Morazán. There were no tortures there, but in nearby locations. Nowadays, it’s a place of healing and a meeting point for forums and educational activities. Both houses stand on top of a hill. From atop, it’s possible to see the entire property, two mango trees and weed-covered concrete sheets, under which it’s believed that human remains were buried. A forensic anthropological work should be conducted to disinter the truths of a place with such an eerie history.