An indigenous reservation in the Colombian Amazon was included in two separate carbon market projects that were approved and have sold credits, in what may have constituted a case of double counting. The promoters of the newer project, which sold credits to the US airline, claim to have made the necessary corrections. However, situations like this undermine the credibility of that market in Colombia.

Andrés Bermúdez Liévano (CLIP)

In September 2022, U.S.-based Delta Airlines purchased 1.3 million carbon credits from a project in the Colombian Amazon so contentious that its fate will have to be decided by the country’s Constitutional Court.

The case reached the highest constitutional court in Colombia after a group of indigenous leaders from the jungle territory of Pirá Paraná that houses it filed a legal challenge against the Baka Rokarire project, arguing that it violated their fundamental rights and that since it was a novel issue it warranted being examined by the Court.

The indigenous plaintiffs claimed that the contract underpinning the initiative was signed by an indigenous leader who had been removed from the legal representation of that territory, in the department of Vaupés, and that it was never taken to the highest governance body of Pirá Paraná. Even before the case reached the Court, the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (CLIP) had uncovered the details of this conflict.

The purchasing airline didn’t comment at the time, but four months later acknowledged that there was a “local dispute over who authorized the project.” Still, Delta stressed its commitment to buying “high-quality carbon offsets,” in line with its 2020 plan to become the first carbon-neutral airline in the United States. This goal, as defined by the company, involved investing in cleaner fuels, more efficient aircraft and, until a change in its sustainability strategy last year, also the preservation of forests – such as the Pirá Paraná -where emissions avoided by reducing logging offset those from the airplanes.

However, this is not the only carbon market project with potential irregularities that Delta has purchased credits from. On December 15, 2022, almost two months after the story warning about the problems with the Vaupés project was published and five months after the indigenous leaders filed their legal action, the airline bought 115,000 credits from a second project with problems in another corner of the Colombian Amazon.

That new project, called Jocū Bucūrō Apūrō, is in southern Guaviare and was approved in September 2022. It was given the green light despite the fact that one of the three indigenous reservations that hosts it already took part in a different carbon project, Redd+ Dabucury, which was active and had sold hundreds of thousands of credits by late 2021.

These are the findings of an investigation conducted by the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (CLIP), as part of the Opaque Carbon journalistic alliance that brings together 13 media outlets from eight countries to investigate how the carbon market is working in Latin America.

By being part of two carbon market projects that were active simultaneously, this indigenous territory and its developers sold the same environmental result twice – something that, in the world of carbon offsets, is known as a form of double counting. In practice, the problem is that when the same environmental result is traded twice by two different projects, it creates a sort of deception of the atmosphere and might lead people to believe that twice as many emissions were reduced than were actually the case. This might question the integrity of a financial scheme designed to connect private companies seeking to offset their environmental footprint with local communities caring for forests to mitigate the global climate crisis. It is also a red flag for the Colombian state, whose digital tool for identifying project overlaps has been out of service since August 2022, coinciding with the timeframe in which Jocū Bucūrō Apūrō was approved.

A developer in charge of each of the projects, as well as the certifier of the newer of the two and the airline that bought the credits, acknowledged to this journalistic alliance that the overlap occurred. They argue, however, that the second project already excluded that indigenous territory from its polygon and that together they found a solution that allowed them to avoid double counting. Despite this, this investigation found that there are still unanswered questions about the due diligence carried out by several actors in those carbon credits’ value chain, about the lucrative sale that had already been made and about how it may affect the credibility of the Colombian carbon market.

The indigenous reservation with two projects

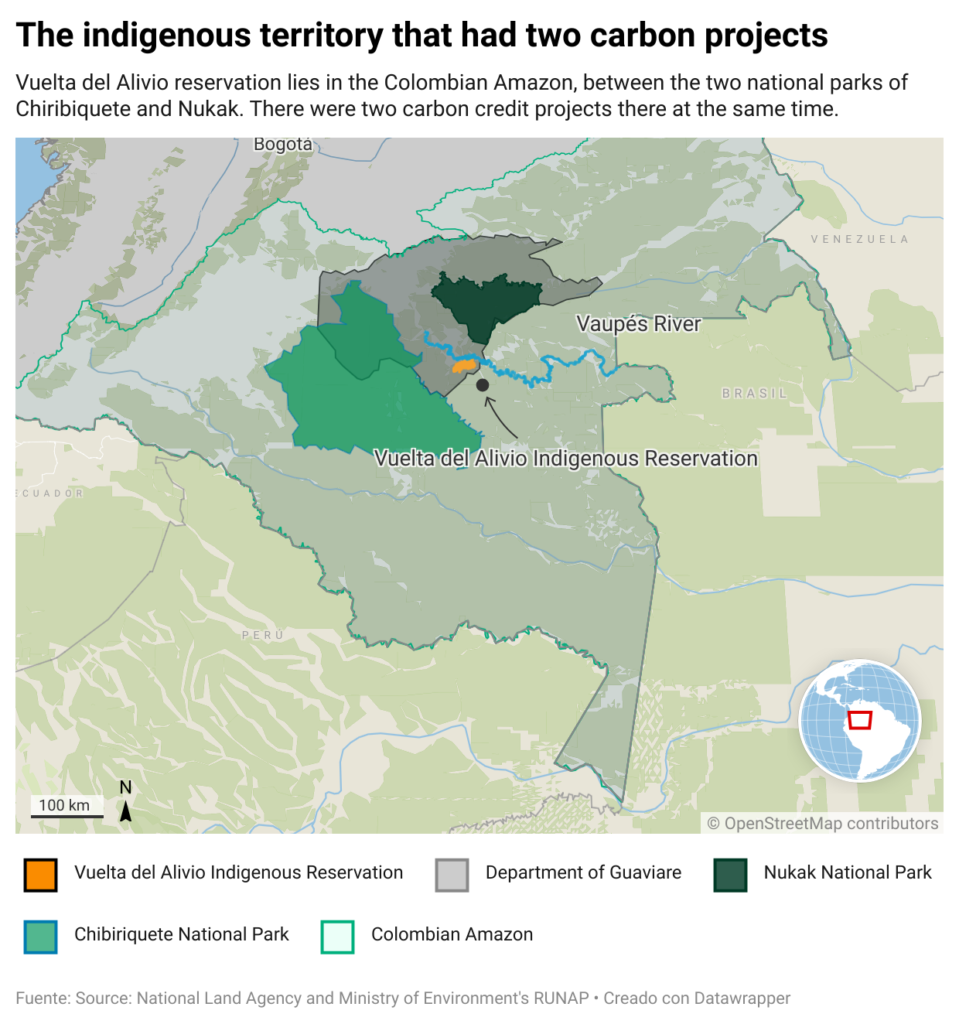

At the center of this conflict is the Vuelta del Alivio indigenous reservation. Created in 1998 and inhabited by some 850 indigenous Wanano people, it lies in a jungle corridor that connects two Amazonian national parks. One of them, the Chiribiquete Range National Park, is the largest in Colombia and also the largest tropical rainforest in the world, considered a world heritage site because of its natural wealth and the thousand-year-old rock paintings that ethno-botanist and explorer Wade Davis dubbed “the Sistine Chapel of the Amazon”.

It is also an area where logging has been on the rise in recent years. The jungle municipality of Miraflores, crossed by the Vaupés River and with the presence of dissidents of the former Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) guerrilla who opted out of the peace agreement, frequently appears as a deforestation hotspot in early warnings published by the Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology and Environmental Studies (Ideam). Between April 2021 and March 2022, it lost 2,742 hectares of forest, according to the Foundation for Conservation and Sustainable Development (FCDS).

That combination of factors makes it perfect for a carbon project. It is a scheme that was incorporated into the United Nations Convention on Climate Change to connect national governments that are slowing deforestation with others that want to pay for those results, but which was then expanded to include private projects. Since then these projects, known as Redd+, have expanded into the raiforests of the Colombian Amazon and Pacific.

There are three reasons for this bonanza. The first is that in 2017 the Colombian government created a tax incentive that allows companies that use fossil fuels to reduce their carbon tax if they buy these credits. The second is that a large part of Colombia’s jungles and forests – totaling 600,000 square kilometers, an area equivalent to the size of Ukraine – is guarded by indigenous and Afro-descendant communities that usually have collective ownership and effective governance of their territories, which is why many companies began to seek them out to promote private projects in the voluntary carbon market. In addition, there is a third one: the possibility of obtaining high profitability, especially when they are being developed without major state supervision of the projects in technical, social and environmental aspects.

In this sense, the conditions of the Vuelta del Alivio’s safeguard seem to have been so perfect for a carbon project that they ended up being chosen by two groups of companies almost at the same time.

The two projects in tension

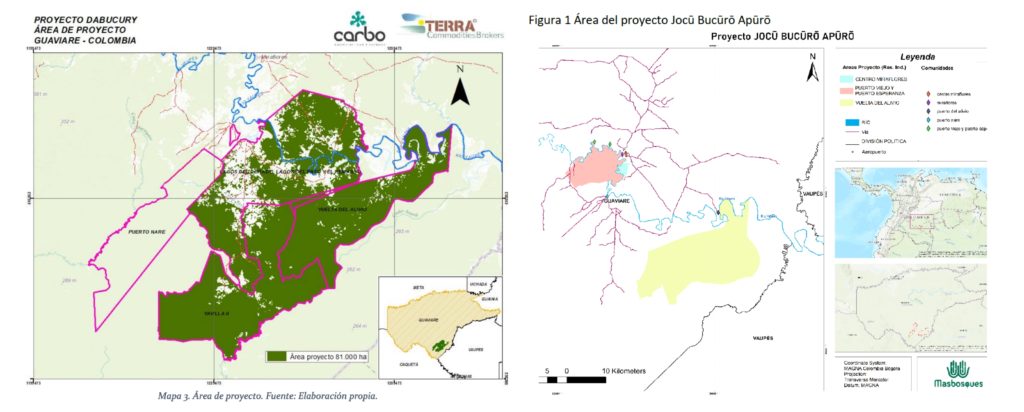

The oldest project, Redd+ Dabucury, took shape and was approved during 2021. Promoted by the Colombian companies Carbo Sostenible, Terra Commodities and Plan Ambiente, it encompasses three neighboring indigenous reservations in southern Guaviare: Yavilla II, Puerto Nare and Lagos El Dorado, Lagos del Paso y El Remanso, as well as Vuelta del Alivio. In the future, the initiative, which is part of the CommunityRedd+ alliance, plans to include a fifth reservation called Barranquillita.

The second, Jocū Bucūrō Apūrō, came to life during 2022. It is promoted by Corporación Masbosques, an environmental NGO from Antioquia that has several public entities as partners, in partnership with the company Soluciones Proambiente. In addition to Vuelta del Alivio, it includes two more reservations to the north, Puerto Viejo y Puerto Esperanza, and Centro Miraflores near Miraflores village.

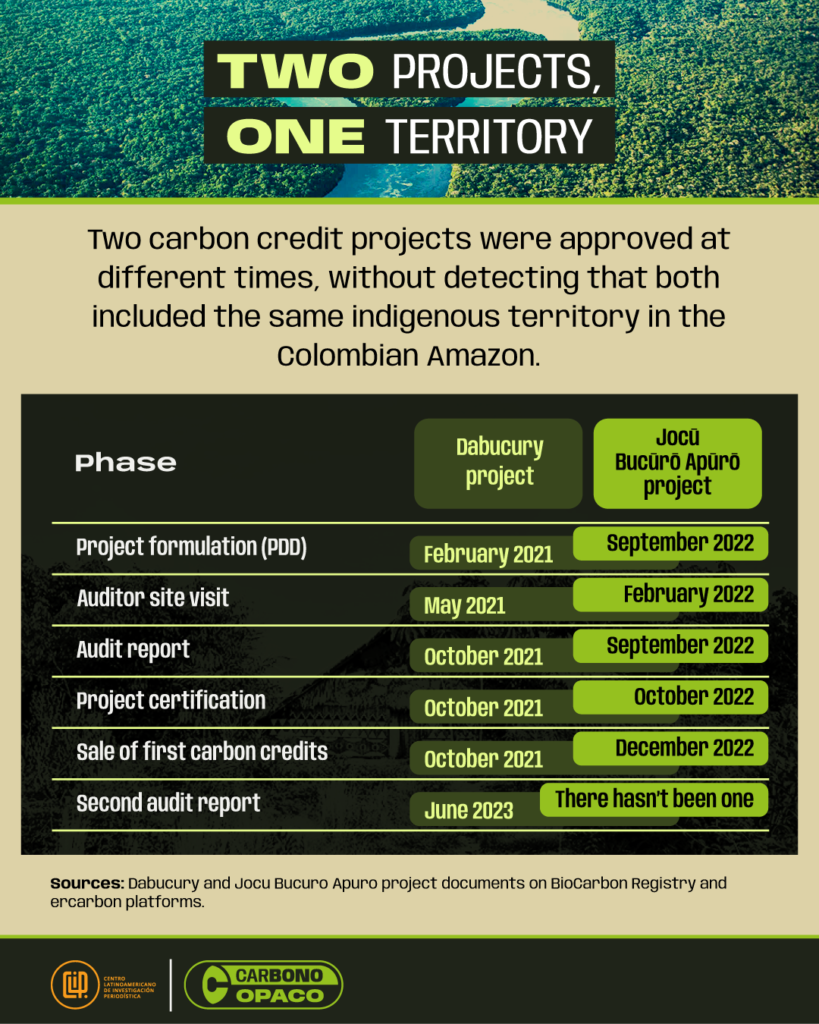

Both initiatives were registered and certified after a validation process. Dabucury went first: it was approved by Colombo-Brazilian auditor Verifit in October 2021 and registered by the Colombian certifier BioCarbon Registry (formerly known as ProClima) that same month. Within five days of being approved, on October 20, 2021, its first 700.000 credit batch was redeemed by gasoline distributor Primax Colombia. Over the next two months, gas distributor Petrobras Colombia reported using 138.000 credits and Biomax used another 5.601 credits. In total, until early 2023, it had sold some 843 thousand credits.

Almost a year later, Jocū Bucūrō Apūrō followed suit: in September 2022 it was validated by U.S. auditor Ruby Canyon Environmental and in October it was registered by Colombian certifier Cercarbono. Two months later, all of the approved credits were redeemed by Delta Airlines.

The supporting documents show that there is an overlap between the two, in space, in time and in the very activity of avoiding deforestation and forest degradation.

The two projects include the same polygon of the Vuelta del Alivio resguardo-408 square kilometers, or the size of the Caribbean country of Barbados-as part of their areas. According to Dabucury’s project design document (or PDD, in industry jargon), that project is on 81,000 hectares of forest, a quarter of which corresponds to Vuelta del Alivio.

Something similar happens with the sales made by both projects. The certificates issued for the credits sold by Dabucury show that they refer to environmental results for the years 2019 to 2020, while those of Jocū Bucūrō Apūrō correspond to January 2018 to December 2021. In addition, both projects list the reduction of deforestation and forest degradation as their activity, and mention the same indigenous leader, Martha Lucía Pedroza, as representative for Vuelta del Alivio.

At least one Colombian state agency, the Sinchi Institute for Amazonian Research, warned of the reservation’s involvement in both initiatives in its report on Redd+ projects in the Amazon launched in July.

Developers of the two projects, as well as the certifier Cercarbono, acknowledged to this journalistic alliance that the overlap occurred and was not detected until the middle of this year, eight months after the second initiative was certified and six months after it sold its inaugural batch of credits.

Indigenous leader Martha Lucía Pedroza of Vuelta del Alivio did not answer Whatsapp messages asking why she signed two contracts for almost identical projects and why she didn’t inform the promoters of both of them of that fact.

Federico Ortiz, one of the promoters of the Dabucury project, said that in June of this year they noticed the overlap and notified Cercarbono, the certifier with whom they have also worked. The latter, in turn, informed Masbosques. “We were stunned. They hadn’t realized,” said the director and shareholder of Terra Commodities. “When they signed for the second time, the project with us was already operating, there was implementation and there were activities.”

Cercarbono confirmed having received this alert, explaining that they immediately ran the polygons through an anti-overlap tool they had recently developed and confirmed that there was indeed a problem. Masbosques noted that it learned of the overlap in an email from Cercarbono on June 15 and met with the certifier and its auditor Ruby Canyon Environmental the following day to corroborate it.

The Antioquia-based NGO says it still cannot explain how the overlap occurred. In a written response, it said it began talks on the carbon project with the local indigenous association Asatrimig in 2020 and signed contracts with the three reservations in November 2021, which it ratified seven months later. Structuring the project, they said, took them a total of two years, between 2020 and 2022. “Masbosques operates from the principle of good faith, fully believing that stated by communities and their legal representative, who indicated that they weren’t participating in another Redd+ initiative,” it added. (Read their full answers here).

As part of that process, Masbosques says it checked that there were no overlaps in Renare, the state platform for mitigation initiatives, and that it corroborated that information through a manual review of the different certifiers’ platforms, finding four projects in Guaviare but none in the area of their interest. “As of April 2021, the date on which the project was registered in Ecoregistry under the Cercarbono standard, no possible overlap was detected,” the NGO argued, adding that it has a no overlap format generated by the government tool.

However, their project didn’t reach the certification stage until a year and a half later. And in that time Dabucury had already come into being and sold its first environmental results, without Masbosques, Ruby Canyon or Cercarbono knowing about it.

The overlap solution

On August 9, 2023, a month and a half after discovering the overlap, the promoters of both projects met in person, with Cercarbono in the mediator role. After acknowledging the existence of the problem, they agreed on a solution. “It was decided to voluntarily withdraw the overlapping areas (…) so that this situation would not cause disputes and divisions within the community,” Masbosques explained to this journalistic alliance.

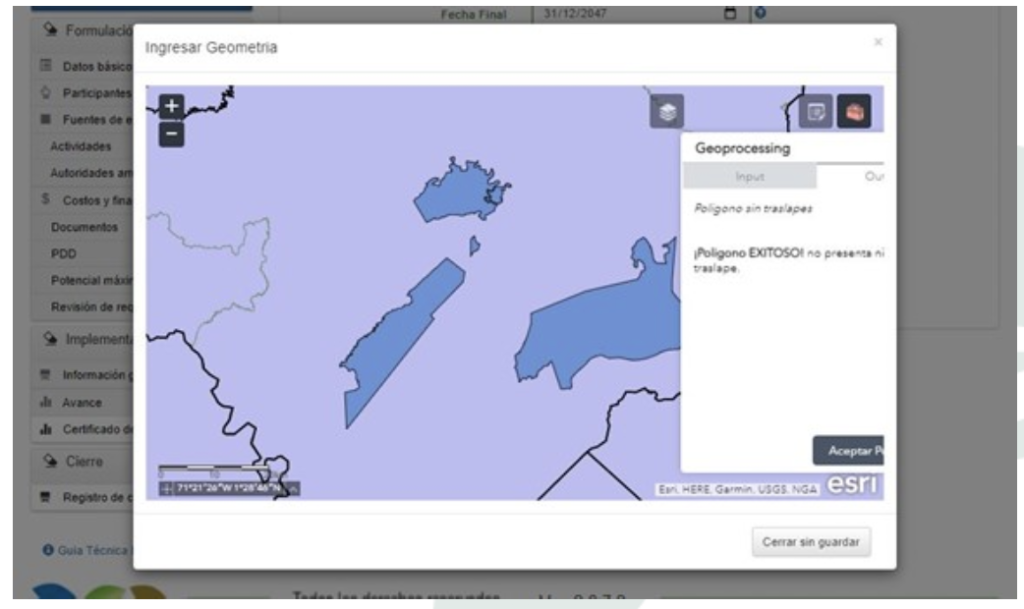

Two weeks later, the legal representative of the Vuelta del Alivio territory formally withdrew from the project and the project’s polygon in Cercarbono’s public registry was redrawn. Jocū Bucūrō Apūrō thus lost four-fifths of its area, going from 51.646 hectares to only 10.776 (although Jocū Bucūrō Apūrō’s documents, however, still include Vuelta del Alivio).

Cercarbono then proposed another solution to solve the second problem they all had: the double counting of the credits already sold. The credits issued by Jocū Bucūrō Apūrō for that territory would be deducted from a buffer that each certifying standard keeps and to which all projects contribute in order to cover -in the manner of insurance- possible risks such as fires or deforestation leaks to neighboring lands. More specifically, Cercarbono covered the overlapping credits with its collective buffer, which is fed with a percentage of credits from all the initiatives it has certified. In doing so, they sought to prevent the Jocū Bucūrō Apūrō project -and all of them- from being held accountable for allowing the double sale of the same environmental outcome. Masbosques then pledged to replace those credits to the certifier with others, something the NGO says it already did “by purchasing credits from other projects from other developers.”

“The area was adjusted, eliminating from the aforementioned project the area corresponding to the existing overlap,” Alex Saer, Cercarbono’s CEO and former director of climate change at the Ministry of Environment during the Iván Duque’s administration between July 2021 and August 2022, told this journalistic alliance. He explained that the certifying standard followed the procedure it outlined for this type of double counting cases, where a number of credits are registered in two different standards, and that it remedied that double issuance through two sanctions that it calls minimum and moderate. These steps, in addition to the agreement between the parties, mean that in Saer’s view “at present we cannot speak of double counting, since the credits issued from the overlapping areas were supported by credits from the collective buffer and in turn compensated by credits acquired by the project to replace them”. (See Cercarbono’s answers here).

That decision satisfied Dabucury’s promoters. “The problem has already been solved,” says Ortiz, explaining that their project just passed a new round of audit with Icontec and that they were waiting for absolute certainty of a resolution before issuing and selling this new batch of bonds from November this year.

When asked by this journalistic alliance how many credits were affected, Masbosques replied that 95.292 – or 82.5% of the total issued by their project. Regarding the resulting revenues, the ONG said that “there was no effect, considering that the funds hadn’t been drawn”.

Delta Airlines told this journalistic alliance that its sustainability strategy changed in 2022, “shifting away from investing in offsets and instead, focusing on decarbonizing our airline operations through efforts including investing in sustainable aviation fuel, renewing our fleet for more fuel-efficient aircraft and reducing overall emissions through implementing operational efficiencies”.

The airline added that, even if it no longer uses offsets to meet its carbon neutrality goal, while it did so it sought to “secure high-quality offsets to achieve their intended, meaningful impact”. Their way of ensuring this, it explained, had been to work with “established carbon market registries that validate offsets with due diligence and credibility at their foundation”. Regarding the problem with Jocū Bucūrō Apūrō project, Delta said that “in this case, the registry -Cercarbono- applied buffer credits from that pool to address the overlap and therefore the process worked as planned.” (See Delta’s complete response here).

In addition to Miraflores and Pirá Paraná, Delta has purchased credits from two other Redd+ projects promoted by Masbosques: in December 2021 it used 300.000 credits from Makaro Ap+ro in Vaupés and a year later, at the same time as those of Jocū Bucūrō Apūrō, it used almost one million from Awakadaa Matsiadali in Guainía.

Everyone blames the government

While the promoters and backers of Jocū Bucūrō Apūrō acknowledge the overlap, they place the primary responsibility on the Colombian government for their own failure to detect a crossover with another initiative.

In its audit report, Ruby Canyon explained that it sought to verify in the state platform but that “at the date of preparation of this report, the Renare web platform was not operational, so it wasn’t possible to carry out this verification”. Masbosques argued something similar in its PDD, explaining that the project was registered in Renare, but that “as of the date of submission of this document and, since last March 2022, the platform is out of operation”. When asked what was the last date it checked, the NGO replied that February 2022 and that it tried again “in the following months but the website was in maintenance”.

Both refer to a Renare digital tool that allows to automatically identify overlaps between uploaded polygons in terms of space, time or activities. In the event of detecting an overlap, it could declare an initiative as “non-compatible” to avoid double counting. A project with such a situation, warns the resolution that regulates the market, “in no case will be able to verify and cancel emission reductions or removals” of greenhouse gases.

Indeed, Renare is currently out of service, but not since March 2022 as Masbosques points out, but since August 9, 2022. As CLIP reported in another report, this was due to a combination of factors including maintenance and a ruling by the Council of State that ordered it to be suspended while it resolves a lawsuit. When asked about this inconsistency in the dates, Masbosques responded that indeed the platform has been down since the second half of 2022, but that “since the first quarter of the year (…) it presented operating errors”.

Even Dabucury promoters share the view that the primary responsibility lies with the Colombian government. “If the state has a tool in operation, why would one distrust it?” asks Federico Ortiz of Terra Commodities. “It’s like a person directing traffic, who usually doesn’t get involved. There has to be a neutral entity that is not judge and jury.”

Even so, Ortiz admits that his competitors lacked due diligence. “When we start a project, although it is not our responsibility, we always find out who the neighbors are, which are the neighboring projects and that there are no overlaps,” he says. Especially because in the absence of Renare there are other ways to check for a possible overlap, such as searching the platforms of the four certifiers operating in Colombia for projects in Guaviare. As of October of this year, according to a manual verification made by this journalistic alliance, there were records of 12 other initiatives, only one of which is active and selling credits.

Dabucury developer Ortiz also points out that the indigenous people of Vuelta del Alivio must have known that they could not sign two different contracts -which usually have exclusivity clauses- for the same type of project. In his words, “they signed with the others having one already in place, probably to benefit their community and without knowing that they were screwing up”. This is a problem, he adds, that can be solved by gradually strengthening their governance capacities.

Overflight audit

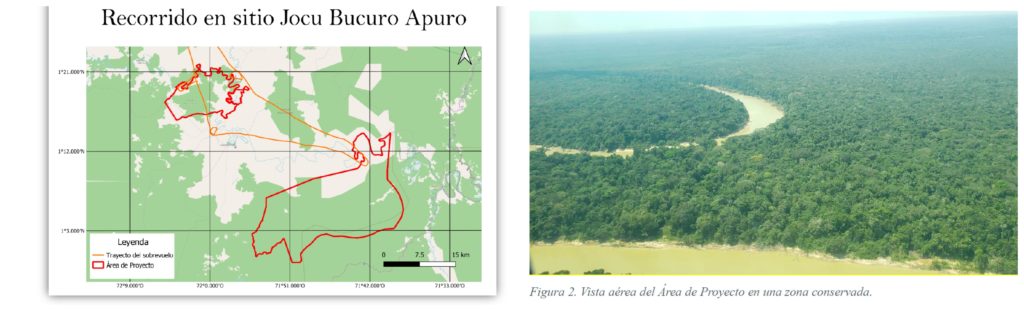

A look at the approval process for the Masbosques and Soluciones Proambiente project reveals a problem that may have contributed to the overlap going unnoticed: the Ruby Canyon Environmental auditors who validated the project did not visit the Vuelta del Alivio reservation, nor did they meet with the community in person.

Their two employees were unable to arrive, their report explains, “due to particular circumstances that arose in and around the project area, related to the activity of armed and criminal groups that generated violence during a period that included the dates of the site visit.” This meant that, according to the document, “the visit had to be adjusted and carried out in a way that included two main activities”: a meeting in February 2022, in the departmental capital of San José del Guaviare, with one of the leaders of the initiative and overflights of the project area.

They only met with Isidro Lomelin Gil, president of the Association of Traditional Indigenous Authorities of Miraflores Guaviare (Asatrimig) to which the reservation in the area are affiliated, given that -according to the report- “due to logistical problems, the rest of the community leaders could not be interviewed in person”. For this reason, telephone calls were held with them, although the report does not say with how many or with whom.

According to the government-affiliated Sinchi Institute, this failure of the auditor shows that “the verification and audit is omitting social and cultural safeguards”.

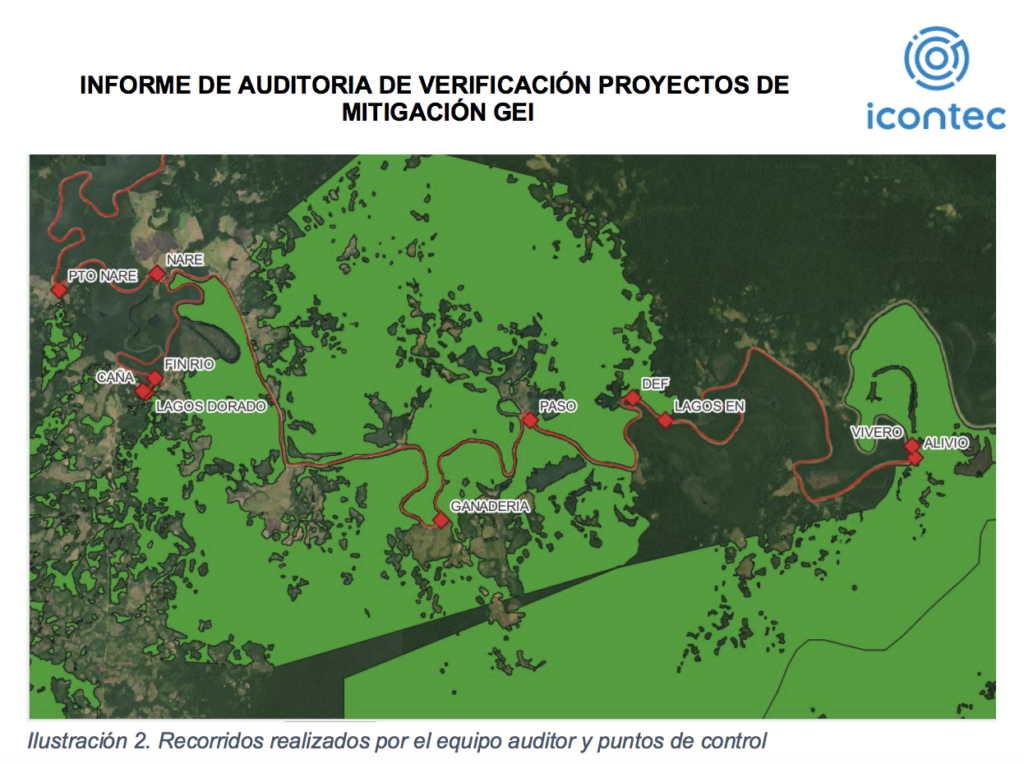

Ruby Canyon’s inability to reach Vuelta del Alivio contrasts with the field visits made by the two external auditors that the Dabucury project has had, both before and after its rival project was validated. First, in May 2021, an auditor from Verifit spent six days in the Miraflores area, going down the Vaupés River to Vuelta del Alivio and meeting with the community, according to its verification report.

Then in December 2022, ten months after Ruby Canyon’s fieldwork on Jocū Bucūrō Apūrō, a second team of auditors from Colombian company Icontec referred an almost two-week visit to Miraflores in its report. They traveled along the Vaupés River to the settlements of Alivio and Vivero, where they met with 21 community members, according to the document.

Ruby Canyon did not respond to an email inquiring about the circumstances that prevented them from visiting Vuelta del Alivio, whether it tried to make a new trip and the reasons why its competitors were able to go.

Curiously, the words that appear in Ruby’s report to explain the reasons why it couldn’t make an in-person visit are -as CLIP’s investigation showed– verbatim the same words that appear in another document made by the same auditor for the project in Pirá Paraná in February 2022, a fact that may have contributed to the auditing company not being aware of the acute conflict that the Masbosques initiative had already generated there and that the Constitutional Court is close to resolving.

When asked why Cercarbono also failed to detect the overlap, CEO Alex Saer explained that the certifying standard always does so using “publicly available information and supporting documentation” and that Jocū Bucūrō Apūrō “complied with Cercarbono’s requirements”. He added that they now have an anti-overlap tool, which he describes as a “state-of-the-art software to assess overlaps more accurately” and “unique in its kind,” but that at the time it didn’t yet exist. “No one could have detected it with the elements available,” said Saer, who in his previous position as Ministry of Environment director of climate change was the government official responsible for overseeing the carbon market in the country.

For the promoters of the affected project, the absence of a field visit meant that the overlap was not identified in time. According to Terra Commodities’ Federico Ortiz, “anyone who goes there should be aware of the project’s implementation” because there are visible signs, like indigenous persons wearing project caps or forest rangers wearing marked vests that they use on their patrols of the territory.

“They explain that due diligence was difficult because of public security concerns. And they are right: it is difficult. But just because it is doesn’t mean they can excuse themselves and not do it,” he says. He did not disclose how much an audit costs, but said that “it’s expensive enough for one to be very picky.”

Same actors, different problems

The Miraflores project is not the first Masbosques project to leave open questions.

As explained previously, in July 2022, the Indigenous Council of Pirá Paraná filed a legal action requesting the protection of three fundamental rights that, in their view, were violated by both Masbosques and the three companies that promoted or validated the Baka Rokarire project (Cercarbono, Ruby Canyon and Soluciones Proambiente), as well as by one of the national authorities that should ensure the proper functioning of this type of climate solutions. “Their actions and omissions in the registration, formulation, validation, verification, certification, overseeing and follow-up of the initiative,” wrote the Pirá Paraná authorities in their legal action, “are seriously violating our fundamental rights to cultural integrity, self-determination, self-government and territory.”

The Constitutional Court decided in April of this year to select the case, after first and second instance judges denied it at the end of 2022. The highest Colombian court for constitutional affairs considered that it meets two of its selection criteria: on the one hand, they will look at whether the judges have observed or disregarded their jurisprudence and, on the other hand, they see it as a novel constitutional issue. Their decision, which could set precedents for the voluntary carbon market, should be announced in the coming months.

This project in Vaupés had two other peculiarities, linked to two other actors involved in the carbon credit value chain.

First, the company that appears in documents as a consultant in the formulation of the Pirá Paraná initiative, Soluciones Proambiente S.A.S., was also its financier and received up to 40 percent of the income the Baka Rokarire project generated, according to what Masbosques employees explained to CLIP at the time. Indigenous leaders critical of the project said that they hadn’t been informed by the NGO leading the project that the company –founded in Itagüí by Mauricio Fernández Posada as the sole shareholder in June 2020- was a capitalist partner of the company.

That company also appears in the PDD of Jocū Bucūrō Apūrō in Guaviare as “project formulator” and in the audit report as the company that hired Ruby Canyon. Masbosques confirmed that Soluciones Proambiente is its “financing partner” in Guaviare -as part of an alliance they now named Sumare- and that it is entitled to 40 percent of revenues minus operating costs.

The second peculiarity of Baka Rokarire is that its credits weren’t purchased from the beginning by Delta Airlines, but by a technology company called Latin Checkout which didn’t use them. The three founding shareholders of Latin Checkout were in turn, as CLIP showed, the same ones in charge of the certifier Cercarbono, meaning those who marketed the credits of a project with potential problems ended up being the same ones who had certified it. On that occasion, Latin Checkout did not answer to whom it sold the credits or in what other projects it has played the same intermediary role. (A Latin Checkout minute, dated March 2023, shows that two of them, Andrés Correa and Alejandro Celis, are now listed as shareholders, with the third one, Carlos Trujillo, having left. The most recent publicly available minutes of Cercarbono, dated February 2021, showed all three as shareholders of that company).

This journalistic alliance asked Masbosques if the company bought or sold Jocū Bucūrō Apūrō credits, but the NGO responded that “unfortunately we cannot provide the requested information as there are confidentiality and reserve agreements in place”. Cercarbono CEO Alex Saer also declined to disclose whether Latin Checkout – which operates its Ecoregistry platform – sold credits from the overlapping project. “Cercarbono is not responsible for the commercialization of carbon credits and therefore has no communication with the end users of these,” he said, adding that “there is no corporate relationship with Ecoregistry and therefore the assumptions stated are not applicable at the present time.” Latin Checkout’s Andres Correa did not respond to two emails asking him the same question. Delta Airlines also did not respond to questions about who it purchased the credits from.

On the affected project’s side, at least one initiative by Carbo Sostenible and Terra Commodities in the Colombian Amazon has run into problems. Their two projects in the Monochoa reservation in the middle Caquetá River excluded two indigenous communities that have historically been part of it, but -as shown in this investigation- included the territory they inhabit within their initiatives. As a result of this, they were marginalized from the benefits it generated and at the same time prevented them from participating in a different initiative. Carbo Sostenible and Yauto, a third company promoting those projects, acknowledged the exclusion and explained that they had already reached an agreement with these two communities to include them. The leaders of these two communities, Aménani and Monochoa, confirmed the agreement. The companies promised that the technical documents would be corrected to reflect this change during 2023, something that had not occurred as of the date of publication of this investigation.

A second group of projects promoted by these same companies in the Brazilian Amazon, Jutaí-1, Jutaí-2 and Río Biá, was pointed out by an Infoamazonia investigation for not having carried out prior consultation with local indigenous communities and ignoring the guidelines of the Brazilian State’s authority in indigenous affairs (FUNAI) on carbon projects in ethnic territories. The companies argue that they were invited by the indigenous people to develop these projects and that they have done so with the knowledge of the local FUNAI office of the Brazilian government.

A credibility problem

The promoters of both projects insist that the overlap problem has been solved and see it as a normal stumbling block in a fledgling industry of which Colombia is a pioneer.

“A lot of people were killed in the first 40 years of the automobile until the safety belt was invented and surely Henry Ford had a number of problems that he gradually straightened out,” says Federico Ortiz, of Terra Commodities. “All industries have these types of flaws when they start, but those who don’t comply are left behind and those working well endure”.

Indeed, there is much to be corrected so that this market, born of good intentions, doesn’t end up discredited. The Miraflores case leaves several alerts that may affect the reputation of the Colombian carbon market. On the State’s side, the non-availability of Renare for more than a year hinders its so far meager efforts to fill the existing regulatory gaps, oversee the market and investigate possible irregularities. The Environment Ministry has a draft norm ready with which it seeks to return it to operation, but there is still no clear timetable as to when this will happen. On the side of the developers, auditors and certifiers, questions remain as to how well they are fulfilling their duty to detect overlaps and serve as checks and balances to each other. And on the side of buyer Delta Airlines, its commitment to buy only “high-quality offsets” might have been undermined by its reliance on “established carbon market registries that validate offsets with due diligence and credibility at their foundation” but who missed spotting the overlap. Add to this the lack of transparency throughout the value chain as to how much carbon credits are sold for and who is involved in these transactions.

Ultimately, flaws such as these undermine the credibility of Colombia’s carbon market and allowed an overlap of two projects that issued credits in the same territory at the same time and for the same activity. In doing so, they gave promoters a free hand to monetize the same positive environmental result twice and companies to also claim it twice as offsets, at least until they detected the problem and sat down to solve it.

Opaque Carbon is a project on how the carbon market is working in Latin America, in partnership with Agência Pública, Infoamazonia, Mongabay Brasil y Sumaúma (Brazil), Rutas del Conflicto and Mutante (Colombia), La Barra Espaciadora (Ecuador), Prensa Comunitaria (Guatemala), Contracorriente (Honduras), El Surtidor (Paraguay), La Mula (Perú) and Mongabay Latam, led by the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (CLIP). Legal review: El Veinte. Logo design: La Fábrica Memética.