Text: Otto Argueta

Translated by: José Rivera

The electoral victory of Bernardo Arévalo and the Movimiento Semilla party in Guatemala, and the response of the people to the multiple attempts to prevent his inauguration and that of the party’s representatives in Congress are signs that a desire for democratic change is a latent force in society. His channels have been massive and diverse protests, international denunciations and legal actions, despite the fact that the judicial system has been one of the most coerced spheres at the hands of corruption. There hasn’t been violence —so far— and while there’s anger against criminal organizations entrenched in the State and the business elite, the population demands the resignation of several public officials (attorney general, special counsels, judges) to make way for the new government, of which much is expected.

Sectors of the population that go out to protest express their outrage at the lack of respect from public officials and the defeated political party, Unidad Nacional de la Esperanza (UNE), to the election results. Guatemalans went to the polls (twice) and voted, an individual decision that, added, becomes a collective decision by democratic means.

Is the outrage at the disrespect for the vote a sign that democracy, despite all its setbacks, has permeated the political culture of these societies? Why is it so uncomfortable to accept it? What does this say to Central America?

The democratic culture in Guatemala is not very different to that of other countries in the region. Like in El Salvador and Nicaragua, a devastating armed conflict marked the beginning of Guatemalan democracy in the nineties. I bring Honduras into the discussion because while it’s true there weren’t any armed conflicts, a counterinsurgent State similar to those in neighboring countries was established, i.e., authoritarian, militarist, corrupt and violent.

The Sandinista ideology didn’t save Nicaraguan society from authoritarianism either and although the discourse was different because of the role that country had during the Cold War, it inherited the same foundations in the transition to democracy: political leaders who had no choice but to participate in free elections and a society that was tired and devastated by so much violence, poverty and fear. Costa Rica is the only Central American country that stayed away from the mayhem and instead strengthened its democratic institutions and economic model to be more inclusive.

Inequality, poverty and injustice persist in Central America and in countries like Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador violent crime rates are the highest outside of war zones. Corruption has been present in every single democratically elected government. There was a transition from having corruption cases to a governmental machinery focused on extracting a country’s natural resources without restrictions and political parties turning into criminal organizations. They considered holding public office as a financial investment that has to be ensured, with profits, during a presidential term.

Those problems, and many more that afflict the region, have multiple causes and while it’s true it can be argued that these causes are structural and historical, it’s because of the consistent benefit they bring to the political and economic elite that makes them so. Behind the structural and historical there are names and institutions that have been in charge of what we know as democracy. Let’s leave aside the fallacy that democracy equals the people. The population votes and participates, but do so appointing representatives who then have the power to make decisions in institutions, which is why they are responsible for the state of democracy. They have the power to listen or suppress, include or exclude, and to strengthen or destroy democracy.

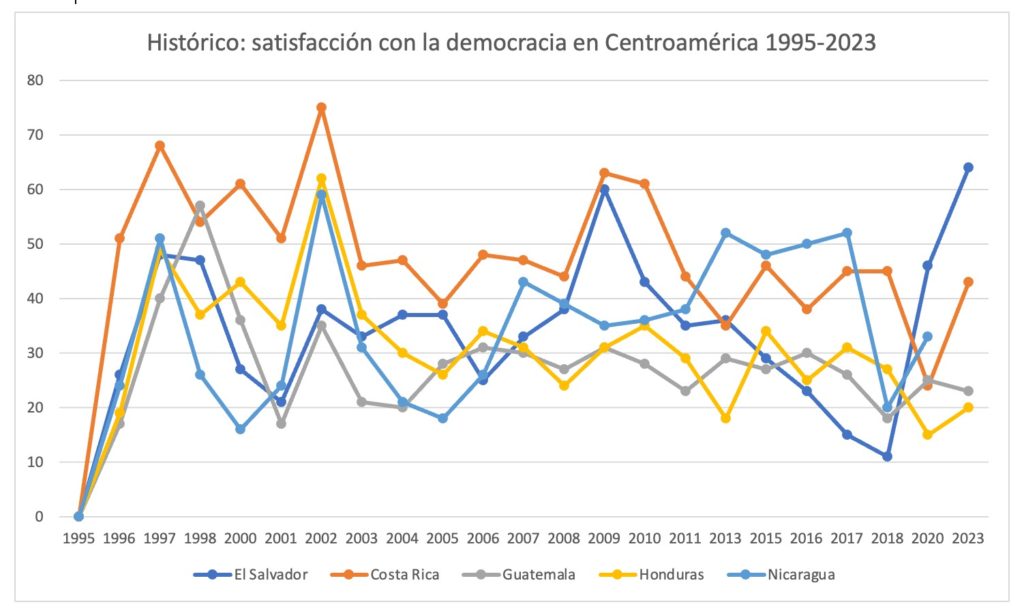

The «third wave» of democracy in Central America was first measured in 1996. Back then, Costa Rica was the only country that had been consolidating its democracy for decades, and according to data by Latinobarómetro, that year 51% of Costa Ricans were satisfied or very satisfied with democracy.

At that time, for the economic, political and military elite in the region democracy was uncomfortable due to the values it demands of its institutions and public officials. For instance, the rule of law, justice, freedom of press and speech, power checks and balances, free and fair elections, etc. For the rest, a population that had been under political violence for decades, democracy was a distant and foreign anomaly, but also what served as a basis for expectations. In 1996, almost a quarter of the population in El Salvador and in Nicaragua was satisfied with democracy, while those figures barely reached 19% in Honduras and 17% in Guatemala.

During the next 27 years, the population’s satisfaction with democracy has gone through different up-and-down patterns in each country. It’s difficult to determine the factors that influence the variability of satisfaction with democracy. There are, however, certain unquestionable factors when data is analyzed in relation to the current political context. It’s possible to infer that those changes are a response to situations in which the population perceives democracy has produced a positive, or negative, result according to their expectations.

In El Salvador, the highest satisfaction with democracy was reported in 2009 (60%) and 2023 (64%). The first government of the Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación (FMLL) party came to power in 2009, after more than two decades of rule by ARENA, a right-wing party that was unable to improve economic conditions for the population, and reduce increasing rates of violence. By 2013, during the second to last year of FMLN’s administration, which was led by president Mauricio Funes, satisfaction with democracy fell to 36%. One year into Nayib Bukele’s presidential term, that percentage rose to 46 and by 2023, it reached the highest point in the history of the country.

Guatemala showed the highest percentage (57) of satisfaction with democracy in 1998, two years after the signing of the Peace Accords. The expectations that the population had as a result of the Accords were reflected in its perception of democracy. Three years later, satisfaction with democracy fell to 17%. It’s possible that financial fraud by businessmen who belonged to Alfonso Portillo’s presidential campaign (2000-2004), clashes between different sectors of the economic elite, the populist rhetoric from the president and corruption during his administration had such an impact in the lives of people that they lost any expectations of democracy.

During the following years, satisfaction with democracy among the population did not surpass 30% and even fell once again to 18% in 2018. That was Jimmy Morales’ second year as president. He and the economic elite laid the foundation of what we now know as the “pact of corruption”, a kleptocracy that adopted a hue of authoritarianism during the term of current president, Alejandro Giammattei.

In 2002, satisfaction with democracy in Honduras was at its peak, 62%. Four years before, the country was devastated by hurricane Mitch, and poverty and the budget deficit for public spending reached such levels of deprivation that the country hasn’t fully recovered. President Ricardo Maduro (2002-2006) appealed to frustrated expectations caused by the mishandling of the crisis by his predecessor, and focused on economic recovery, the cancellation of foreign debt, investment on education and —the Central American recipe— a “tough on crime” policy.

However, as aggressive as these policies are, their effect on human rights and legitimacy do not go unnoticed by the population. By the following year, satisfaction with democracy had fallen to 37% and remained at that level until 2018, when it dropped to 18%. That year Juan Orlando Hernández began his second presidential term following a reelection that violated constitutional principles. Not even the 2009 Coup caused satisfaction with democracy (35% in 2010) to drop as much as cheating in the elections and the role of public institutions did. Hernández’ administration interpreted the law to their whim, and those institutions supported him when they should’ve ensured constitutional order.

Nicaragua had the lowest levels of satisfaction with democracy in 2000 during the administration of Arnoldo Alemán, head of a corrupt government who was later sentenced to 20 years in prison for money laundering and corruption. Arnoldo Alemán and Daniel Ortega, fierce opponents, polished the rough edges in their ideologies with a pact that ensured their continuity in power. One of the most important benefits Daniel Ortega obtained from that pact was to lower the percentage of votes needed to win the elections to 35%, that’s the highest percentage of votes he had, in the previous elections. The pact made way for the alternation of governance between Ortega and Alemán, but this changed when the latter was sentenced allowing Ortega to establish his long-standing dictatorship.

In 2002, satisfaction with democracy in Nicaragua reached 59% at the time when Alemán left office. Expectations rapidly declined and remained low to date, data that is not available anymore due to the government not allowing opinion polls from domestic and international institutions.

Satisfaction with democracy is a perception and, as such, it’s affected by multiple variables with a high amount of subjectivity and symbolism. That’s why it’s unstable and depends to a large extent on how political leaders behave, how they communicate and how people feel their vital needs are addressed, even if they aren’t. In Central America, political leaders have been erratic, contradictory and ambiguous when it comes to committing to democracy. From different ideological positions, public officials have justified their antidemocratic actions by blaming democracy. Nayib Bukele champions a libertarian discourse with which he discredits the State’s responsibility to ensure public accountability and respect for the rule of law. Daniel Ortega and Xiomara Castro champion a left-wing populist discourse that discredits democracy for being “liberal and fitting of the middle class”. In Guatemala, Alejandro Giammattei simply ignored any stance on democracy undermining it by granting antidemocratic and criminal actors the liberty to act without restrictions. Those are few of the many actions by a political and economic class that undermines democratic support for the population.

According to Latinbarómetro, Guatemala is one of the countries that is going through a democratic recession. Guatemala and Honduras, with 29% and 23%, respectively, are the two Latin American countries that show the lowest percentages of support for democracy. But most of the population show a worrying indifference to the regime in power, whether it’s democratic or authoritarian. Honduras scored the highest on indifference in the continent with 41%. It’s in that portion of the population that the possibility to reinforce democracy or expand populist authoritarianism lie.

Political leaders who degrade democracy by burdening their principles with irresponsibility or lack of commitment are indifferent to the fact that dissatisfaction among the population is with the actions of the political and economic elite, not with democracy as such. For a large part of the population in the region, democracy may have its problems, but it’s the best system of government, as polls showed, 80% in El Salvador, 72% in Costa Rica, 57% in Honduras and 52% in Guatemala. In other words, the population may accept an authoritarian or populist regime after a political or social crisis, but sooner or later, they will demand those same freedoms lost supposedly in response to needs authoritarian populist governments pretend to address.

When political and economic elites accumulate wealth and power by undemocratic means, democracy makes them uncomfortable. Accountability of the use of public resources, independent press, autonomous and organized civil society, democratic checks and balances don’t make them uncomfortable because of ideological reasons, but rather because they expose the injustice, impunity and corruption of the elites to the rest of the population. With that in mind, just like Latinobarómetro shows, the higher the social class, the lower the support for democracy. In Latin America, support for democracy among the upper class is just 37%. It’s important to note that in Central America, where most of the population is poor (for instance, 7 out of 10 Hondurans are poor), the upper class constitutes a large part of the State’s bureaucracy. Support for democracy among the lower class in Latin America is not too high either (44%), which is logical considering that most people are more concerned about surviving. The highest support for democracy in Latin America is found among the middle class at 51%.

The problem is that in Central America the middle class is very small and keeps shrinking, According to a study by the Central American Institute of Fiscal Studies (ICEFI) with data from the World Bank, a person who earns between $13 and $70 a day is part of the middle class; someone who earns less than $5.5 is poor, and someone who earns more than $5.5 but less than $10 is at risk of falling into poverty. In 2019, of the 49.7 million inhabitants in Central America, about 17.2 million were poor (1 out of 3). Forty percent of the population was living in vulnerable conditions and just 26.2% was considered middle class. After the pandemic in 2020, poverty increased in the region and the middle class shrank by 8.8%, that’s 1.1 million Central Americans who are no longer part of the middle class. A large percentage of the population in vulnerable conditions became poorer, 2.1 million Central Americans fell into poverty by 2020. The Honduran middle class was the most affected and the World Bank calculated that there was a reduction of one-fifth and that 70% of people who recently became poor live in Honduras and Guatemala. The middle class represent 50% of the population in just two countries, Costa Rica and Panamá.

Under these conditions, democracy is uncomfortable because its principles put the continuity of the model at risk. A model that seeks the accumulation of wealth and feeds on poverty and the indifference it produces. In addition, populist and authoritarian governments turn aggressively against the middle class, and build their messianic rhetoric appointing themselves as the voice of the people. It matches the eagerness of the traditional economic elite who feels threatened by democracy. In Central America, the political and economic elite support one another as an upper antidemocratic class. Authoritarian populists extol “the poor” without changing the economic structures that perpetuate their social condition and this is convenient for the upper class because its accumulation of wealth lies in the continuity of those structures and the existence of poor uneducated workers who accept meager wages. Both tend to reject the democratic voices of the middle class demanding liberty, equality, equity, justice, free markets, transparency and public accountability.

The shrinking middle class in Central America clings to authoritarian populists to the extent that they obtain an assurance that doesn’t allow them to fall into vulnerability or poverty, especially if a large part of that middle class lives off the State’s bureaucracy. But sooner or later, the middle class, maybe temporarily indifferent to the type of regime in power and unlike other segments of the population, will demand fundamental liberties.

That same middle class in Guatemala rejected the political elite and the traditional private sector, and chose democracy instead. In every Central American country there are medium-sized businesses owned by young people who are affected by the traditional large businesses. There are also political leaders who no longer identify with the overused left and right-wing ideologies and see communists or agents of the empire in every corner. When they understand that favoring one group, dogmatic ideologies and the concentration of power are a gamble and, sooner or later, will be counterproductive; and betting on them will only contribute to perpetuating a culture of violence, blackmail and discredit that increasingly exhausts, impoverishes and disenfranchises the population. That’s when they will be able to defend that democracy is something more than just elections, it’s a set of guiding principles from inclusive institutions, a future in which individual well-being is not excluded, but nurtured by the collective well-being, and liberty is an incentive, not a threat.

In view of the rise of right and left-wing populists who are united by corruption and crime, it’s revolutionary to be a democrat, to establish the basis of democracy and to keep doing so.