Text: Jorge Paz Reyes

Photography: Jorge Cabrera

Yesterday, Guatemala held the second round of its presidential election. During the first round in June, the country experienced something unexpected: the underdog, a party founded by academics and progressive reformists, garnered enough votes to make it to the second round. During the first round, Semilla received little to no attention, and no one ever really considered its candidate, Bernando Arévalo, as a possible forerunner in the second round, let alone the winner. But yesterday history was made.

To put it in a U.S. context, Bernardo Arévalo is like the Bernie Sanders of Guatemalan politics; his platform is anti-corruption, progressive, and appeals, especially to the youth. He is even called Tio Bernie online, and his social media presence is powered by Semichi, a cat who made a famous appearance during one of the party’s press conferences. Well, now Semichi is all the cats that are Guatemalan and leftist.

The Semilla movement is driven by young university students and professionals. It was founded in 2015 by a group of intellectuals, political consultants, members of civil society, and university students. Since then, the party has secured 23 seats in Congress out of 160, a decent amount but definitely not enough to make a presence. All experts agree that the youth played a key role in giving Semilla a chance in the first round, and yesterday they achieved the unexpected.

Conozcan a Semichi 🌱✨😺

— Movimiento Semilla 🌱 (@msemillagt) July 13, 2023

Gracias @ColectivoGUASA pic.twitter.com/mMdIkHNaUI

“Semichi against the corrupt rats”

“The unlikely result of conviction and perseverance!” said Bernardo Arévalo when he learned he had made it to the second round in June.

The chances of Arévalo making it to the second round were slim, he was ranked 8th in several polls, but the likelihood of him winning the election was unthinkable.

The surprising thing about the results is that Arévalo was running not only against Sandra Torres, former first lady, representative of the UNE party, and hand-picked candidate of the establishment but against an entire corrupt system.

In politics, it is never wise to label one side as bad and the other as good, but in this case it was clear who the villains were. The force behind Torres’ campaign is known in Guatemala as the “Pact of the Corrupt,” a group of politicians, military officials, businessmen, and alleged drug traffickers who have taken over the country’s Congress and judicial system.

According to international organizations and several Guatemalan officials, the Pact has co-opted the country’s Attorney General’s Office, the Supreme Court, and several government institutions. In Congress, the pact, made up mostly of the UNE party (28) along with the current governing party of President Alejandro Giammetti, VAMOS (39), holds 67 seats, giving it control of almost all branches of government.

This control allowed Sandra Torres and other right-wing candidates with close ties to the “Pact” to dominate the presidential elections and eliminate any potential challenger. Before the first round in June, Guatemala’s electoral tribunal barred 4 candidates from running. Three days before the first round, on June 22, the New York Times revealed that members of the president’s party had bribed judges at the electoral tribunal to prevent some candidates from running.

Semilla did not appear to be on the radar and was allowed to remain in the race. However, her unexpected rise to the second recond definitely set off alarms.

The past month has not been easy for Semilla and Arévalo. After the results of the first round, the Attorney General’s Office announced an investigation into Semilla for corruption and irregularities in the party’s guidelines. The investigation was initiated by two prosecutors sanctioned by the United States for their links to corruption.

Semilla has had to deal not only with the legal challenges of the system but also with the smear campaigns launched by Sandra Torres. Since Arévalo’s political agenda focuses on leftist reforms and social diversity, the “pact” went for the old standby of accusing Semilla of being radical communists. Its supporters pushed the same narrative that we hear throughout Latin America when leftist movements appear on the political scene: “They will turn Guatemala into another Nicaragua, Cuba, or Venezuela.

But despite the odds, Semilla succeeded: as of 12 a.m. on Monday, August 21, the election results show an irreversible trend that favors Bernardo Arévalo as the winner of Guatemala’s 2023 presidential elections. With 98% of the ballots counted, Arevalo leads with 58.8% compared to Torres’ 36.4%.

History repeats itself. But in a good way, we hope

But who is Bernardo Arévalo? Well, Arévalo is not a nobody; in addition to being a sociologist with a Ph.D. in philosophy and a career politician, he is also the son of Guatemala’s first democratically elected president, Juan Jose Arévalo.

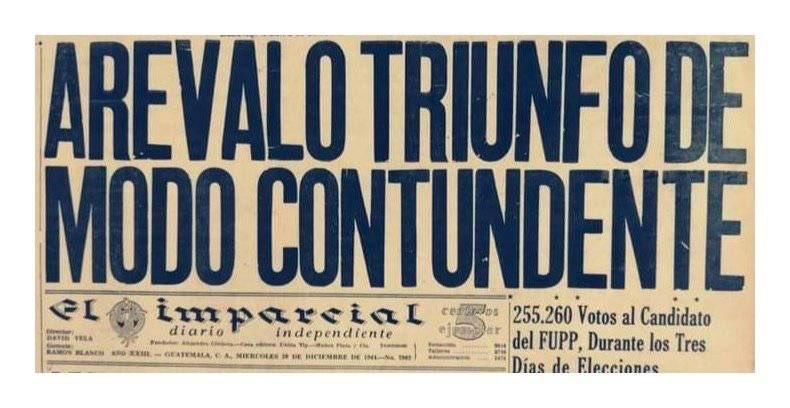

Before the infamous U.S.-backed coup of Guatemalan President Jacobo Arbenz in 1954, his predecessor, Juan Jose Arévalo, laid the groundwork for what is now known as Guatemala’s 10-Year Spring (1944-1954). Former President Juan Jose Arevalo was elected president in 1945 after a political uprising in 1944 against Guatemalan dictator Jorge Ubico, who controlled the country for 12 years and catered to the United Fruit Company.

During his tenure, Juan Jose Arévalo dealt with more than 25 coup attempts and was under constant pressure from outside forces such as the United States. But he continued to push for reforms and led the country to prosperity. When he handed power to President Jacobo Arbenz in 1951, he remained in the government and pushed for progressive legislation. But when the U.S.-backed Guatemalan elite staged the coup against Arbenz in 1954, he left the country in exile. Bernardo Arévalo was born in Uruguay and did not return to Guatemala until he was 15.

The parallels between Arévalo the father and Arévalo the son are striking. Both Arévalos rose to the presidency in a highly unstable political scene, and like the father, the son hopes to implement a series of reforms that will help move the country forward.

But like his father, Bernardo Arévalo now faces the challenge of fixing a system that has been broken for years. Almost all branches of government are controlled by the “pact,” including the current members of the country’s Attorney General’s Office, which Arevalo will now have to deal with for at least two years until the next elections.

In an interview with Contracorriente just before the elections, Arévalo addressed the challenges his administration would face within Guatemala’s political scene.

Regarding the judicial system, Arévalo stated, “…the corrupt are not going to go away and [they will] stay in power, they are going to be there and they are going to be a problem. We have been very clear, we do not have the legal capacity to intervene in the justice system and we are not going to do it because if we really get involved in violating laws then we are justifying whatever they want to present and they have no cover, so it makes no sense, we are going to respect and we are going to work within that”.

But when it came to Congress, he was clear. “Everyone says to me, but how are they going to do it with a Congress that is totally full of corrupt people, well, how are they going to be corrupt when we are going to close the stream that feeds corruption, which is the public works budget, because today the budget is where the business between mayors, deputies and public officials is tied up,” he explained.

The reality is that the prospect of Arévalo’s administration is not one of compromise but of challenges and needed reforms. Despite the results, many are still unsure how things will play out in the long run. History repeated itself yesterday, in a good way, but let’s hope that this time democracy comes out on top.

Central Americans: hopeful but skeptical

For hope to really take hold, the current government needs to transfer power, Semilla needs to form a government, and promises need to be kept.

As a community, Central Americans are very hopeful but at the same time skeptical. Bernando Arévalo triumphed over a sea of corrupt candidates, but there is still work to be done.

First of all, he has to make it to the presidency. He won, but in the Central American region, the future is always uncertain, especially in a country as corrupt as Guatemala. Second, he needs to consolidate his government and get the ball rolling in the right direction.

Defeating the establishment does not always mean that the problems go away. We saw something similar in Honduras when President Xiomara Castro won the 2021 elections. The establishment was defeated and the narco-state was over, hooray! Everyone was momentarily hopeful for change.

But soon after, President Castro began to move in the wrong direction. What began as a government for the people, with the goals of demilitarization and democracy, has now become a nest of nepotism, where civic spaces are increasingly undermined by mano dura practices like those seen in El Salvador and Nicaragua.

The good sign is that, unlike Libre, the political party of President Xiomara Castro, Semilla has different origins. The Semilla movement was founded with a clean slate by independent minds and intellectuals with an evolving vision for Guatemala’s future. Libre, on the other hand, was founded in the context of the 2009 coup and an already highly polarized political past.

Arévalo also explained, “There is an expectation, what we have to do is to start demonstrating two things: one, that the fight against corruption was not an electoral slogan so that they would vote for me, and then once [the election] happened I would start behaving like everyone else, appointing relatives, doing business, and so on. The second thing is to get the institutions to start producing results, that there are tangible, small things that can be done because we are going to get a state in pieces, but we are going to start showing that there are things that are happening.

Another thing is that Bernardo Arévalo’s campaign was always straightforward; Sandra Torres gained much of her support through clientelist practices, a vote for a bag of food. But the Semilla movement has always kept a low profile, far from populism and patronage. Its goals have always been the same: democracy, equity, a humane economy, a pluralistic nation, and respect for the environment.

In the region, Guatemala has always been a precursor of change. When the Guatemalan dictator was overthrown in 1944, Hondurans were inspired to begin their own socio-political changes to remove their own dictator. When President Arbenz was ousted from power in 1945, Che Guevara began to question the role of U.S. imperialism in the Latin American region. And when Guatemala established the International Commission Against Impunity (CICIG) in 2006, it set a precedent and a desire for the entire Central American region to clean up its corrupt governments.

Currently, the region is facing a democratic crisis. As our editor-in-chief, Jennifer Avila put it, the governments of Central America are “all from different ideological tints, from the far right to the left to tropical libertarianism, but they all agree that democracy is a nuisance”. So let’s hope that the seed that was planted yesterday will become a model of reform for its siblings and that we all move away from this authoritarian chapter of our history.

This note was possible thanks to the coverage of our editor-in-chief, Jennifer Avila, and political science expert and analyst, Otto Argueta Ramirez. They, along with our photography editor Jorge Cabrera, have been out on the streets of Guatemala documenting the reality that millions of Guatemalans are living right now.