The Argentinean consultant, an excentric and provocative character, broke into South American politics in 2020 for his intervention in electoral campaigns in digital media for the far-right. Although his past is a mystery, Cerimedo has installed himself with controversial campaigns that included disinformation in Chile and Brazil. His next goal is to make far-right MP Javier Milei President of Argentina.

By Iván Ruiz (CLIP), Manuel Carricone and Martín Slipczuk (Chequeado), Francisca Skoknic and Ignacia Velasco (LaBot), Alice Maciel and Laura Scofield(Agência Pública), Juliana dal Piva (CLIP/UOL Noticias) and Tomás Lawrence (Interpreta).

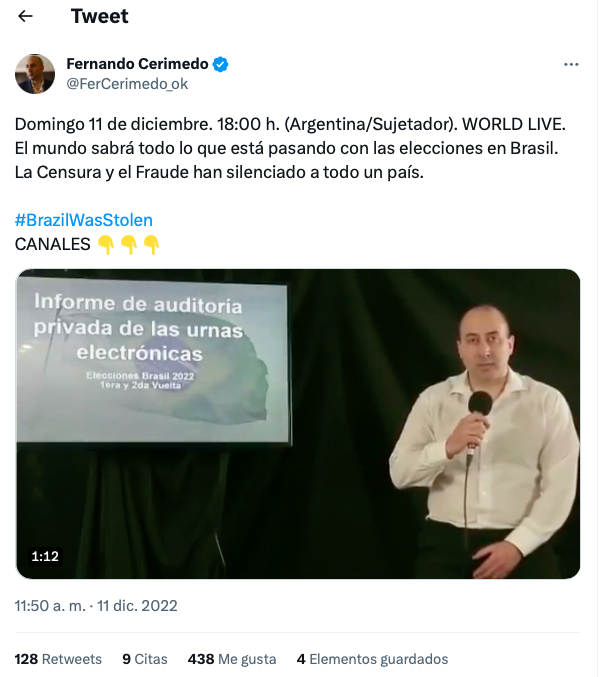

Jair Bolsonaro’s defeat in the Brazilian elections opened an opportunity for Fernando Cerimedo to position himself as a reference of digital communication for the Latin American ultra-right by replicating the story of “the big lie”. “This Sunday, the world will know everything that is happening with the elections in Brazil. Censorship and fraud have silenced an entire country. #BrazilWasRobbed,” the Argentinean consultant wrote on Twitter. This would be the prelude to the service he performed for Bolsonarismo at the end of last year, when he gathered 400,000 people in a YouTube “live” to question, with false information, the legitimacy of Lula da Silva’s victory.

Cerimedo’s intervention, which he later repeated before the Brazilian Senate, fuelled the violent demonstrations staged by Bolsonaro fanatics throughout Brazil that culminated, days later, in attacks on Congress and the Government Palace in Brasilia. The Brazilian right spread messages like those with the help of the Argentinean, sowing doubts about the legitimacy of the Brazilian electoral system through channels such as Telegram. The Brazilian Superior Electoral Court ordered the suspension of Derecha Diario accounts on social media, of a video by Cerimedo and of the personal account (which was later reinstated) he used for misinforming. For the same reason, Bolsonaro himself was disqualified at the end of June from holding public office.

Disinformation about Brazil’s alleged electoral fraud was the end for Bolsonaro, but it boosted Cerimedo. “I am a hero to half the country. They call me the most beloved Argentinean in Brazil” says the consultant proudly. With similar antics, the Argentinean intends to become a reference for the South American right after having spread messages based on lies in Brazil, Argentina, and Chile, as told by a journalistic alliance of 20 media, five organizations specialized in digital research and students of a master class at Columbia University coordinated by the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism, CLIP.

“I took on this role as consultant to the Latin American right because everyone is afraid to put on that suit. For many people, saying you are right-wing is a bad word, but not for me,” he said. With similar ease he admitted to this investigation that he does have many trolls, referring to fake accounts in social networks that interact with a defined script to falsify conversations. But he maintains that he doesn’t use them to attack political opponents or to put likes on his candidates’ content, but to trick the algorithms and, in that way, position his clients’ messages more effectively.

Cerimedo appeared as if out of nowhere. From being practically unknown, in less than four years he set up a business group based in Buenos Aires integrated by his advertising agency, Numen SRL, and an academy that offers digital and political marketing courses, according to official sources consulted by this alliance. He claims that he also manages 30 small websites and a private security company, and in total hires almost 200 employees. Among his websites is “La Derecha Diario” a domain he owns since 2018 and a news portal he created to “influence” the right’s ideological sector. His partner, chemical engineer Natalia Belén Basil, is the platform’s director and is listed as its founder, as well as appearing as Cerimedo’s business partner in Numen Publicidad and Academia Numen.

Despite the great deal of evidence of the falsities published by this outlet, Cerimedo denies the claim. On a videocall with us, he disputes accusations one by one, using arguments often based on half-truths to come out unscathed of the interview. “Calling us serial disinformers for two or three minor things is the only way they have of beating us. I am against fakes news”, he assures, as he downplays the disinformation published by Derecha Diario, calling them “pranks”, “banter”, and “silly jokes”. But they are not.

“La Derecha Diario is the only one of my outlets that makes mischief”, he concedes. He is referring to pieces such as the one that claimed that Kirchnerism had prior knowledge of the assassination attempt against Cristina Kirchner because the TV channel C5N (partial to the vice-president) had miss-dated a piece as if prior to the attack, due to a technical error with time differences in the server, and which was used by the right to add fuel to an already inflamed social environment. “Yes, it was a childish thing to do. They told me the following day that we had published it, and I said: ‘if it was staged, nobody is stupid enough to publish the news five hours earlier. These are minor things,” he insists.

Cerimedo, 42 years old, is full of contradictions. Today a self-described right-wing activist, just three years ago was organizing the digital activities of the Peronist Youth in La Matanza, a key district for Kirchnerism. He crossed over, he says, for love: “My wife is a fan of Javier Milei”. His appearances alongside the Bolsonaros allowed him to get closer to Milei, a congressman who aspires to win Argentina’s presidential race this year. Cerimedo is now head of communication of Milei’s campaign, but he will also be overseeing voting. In a sort of Brazilian deja vu, the consultant has already asked the Argentine government for information on the electoral system to avoid “irregularities” in the elections, the same steps taken by Bolsonaro and Trump to question the results of the elections they lost.

From Obama to Peronism

Cerimedo loves to present himself as a globetrotter who has lived more than one life. As a 19-year-old law student he left his hometown of Mar del Plata, he says, with a Harvard scholarship for his sporting skills in triathlon. But he could not study at the prestigious university because he did not speak English, so he settled in Puerto Rico. His American journey included a supposedmilitary training with the Navy Seals (a special operations force of the U.S. Navy), after which he did a PhD in marketing at the University of Phoenix. “One day my thesis tutor told me he loved what I had presented and took me to work for [Barack] Obama’s campaign in the Democratic Party primaries. Because we won, I then led teams in the presidential and went on to work in the White House. I spent a few months in the International Affairs office. Then I went to a government security agency that sent me to different countries in Latin America to help politicians that the US was interested in”.

A source close to the Obama campaign and who worked in his administration said he did not recognize Cerimedo’s name or that of his alleged mentor. There is no office in the White House with the name International Affairs.

Beyond his own version peppered with big names, Cerimedo’s past seems a mystery. His name only started gaining recognition after the creation of Numen in 2020. Before that, his employment history, as far as it can be reconstructed from other sources, seems a little bit less grandiose. Cerimedo appears as an employee of a cab company in Mar del Plata in 2014 (Mardeltax SRL), then worked for an insurance company in Buenos Aires (Europ Assitance Argentina SA), for a computer products business (Sentey SA) and for a plastics factory (Alfavinil SA) in 2015, according to information in the private Nosis database. He was creative director of advertising agency McCann in Argentina until 2018. That same year, and then in 2019, before founding Numen, he worked for a few months as a high school teacher for the City of Buenos Aires, as official sources reported.

On his interview with this alliance, Cerimedo said that a course at Harvard opened an opportunity for him. “I took a postgraduate course in Political Communication at Harvard University in 2010 and there I met Eduardo Bolsonaro. We were the two Latinos who spoke mixing Portuguese and Spanish. Eduardo is very fond of everything related to the police and since I have a military background, I trained for a long time with the Navy Seals, we hit it off well”. This journalistic team asked Harvard University about this course, but the university said that there were no records of “Eduardo Nantes Bolsonaro” or “Fernando Gabriel Cerimedo” as students of the institution. When asked about it by e-mail, Cerimedo stated that he took four open courses at the university and so he is not listed as a student.

Despite his dubious version of how he met Bolsonaro, Cerimedo says he worked on his 2018 presidential campaign. “I entered in the last 40 days, when everything had gotten very rough. We worked in parallel to the official campaign to convince Bolsonaro haters, like homosexuals. We also did contrast campaigning, which is to show everything that the rival candidate does not want to be known.” This is also known as negative campaigning.

Cerimedo was unknown at the time in Argentine politics. Malvinas Argentinas, a municipality in the province of Buenos Aires, hired him in 2019. He had been commissioned to do “social media positioning” work for the municipal elections that ended with the re-election of Peronist mayor Leonardo Nardini, a leader who had been an advisor to Alicia Kirchner, the sister of the former president. His good performance opened the door to the strongest electoral bastion of Peronism: the municipality of La Matanza, in the province of Buenos Aires, the most populated in Argentina. Peronism has never lost in La Matanza since democracy returned to the country in 1983, and Cerimedo did his bit to ensure that Peronism remained in power in one of the poorest districts in the country.

“We were the world champions in winning elections in the street. We knew how to knock on neighbors’ doors and convince them, but we knew nothing about the new territory of social media, where militancy is also needed. Cerimedo brought Matanzas Peronism into this unknown world”, a Kirchnerist source recalls. His advice was key to organize the work that the younger militants were already doing in social networks: “He taught us how to organize ourselves, how an algorithm works, how to better position a topic, how to reach segmented users”. Mayor Fernando Espinoza was re-elected in 2019. Kirchnerism in Matanzas still fondly remembers the “charming madman” who suddenly crossed over to the opposing party.

The first strike that gave Cerimedo media prominence did not occur in Argentina, but in Chile. In September 2020, newspaper El Mercurio published a survey carried out by Numen that assured that the gap was narrowing between In Favor and Against the referendum for a new Constitution for Chile. It was a surprising result because all studies up to that moment predicted a comfortable triumph in favor of the new Constitution.

Cerimedo’s company claimed to have conducted more than 18,000 online surveys, an unusual number for a poll, which usually does not exceed 3,000 participants. The study, which had been financed by businessmen supporting the “Against” vote, was later used in social networks by those same sectors to try to change the electoral mood. At that time, poll results did not credit the manipulation attempt: “In favor” won with 78% of the votes. But in the imagination of the right wing the idea remained that it could win. (See more details in a story by this journalistic alliance “Arbiter of the Chilean constitution is partner of a disinformer”).

Cerimedo qualifies that intervention as a “failure”. “The error was we analyzed and projected the data with mandatory voting, 100% voter turnout”, he justified himself in an interview with La Tercera, where he attributed the error to a presentation problem, obviating the fact that the vote was voluntary, that a 100% turnout was impossible, that his calculation of likely voters was overestimated, and his methodology had been questioned. In other words, it was a misleading survey to favor the position of the businessmen who commissioned it. In the interview with the Chilean newspaper, Cerimedo further argued that “we are not pollsters, we are not a polling company” (although they offer this service on their website) and said that they use them as input to design a “digital strategy plan for the “Against” vote”.

With Gabriel Boric now in power, Cerimedo appeared again in Chile for the referendum regarding the text of the new constitution. “I did all the part of the communicational strategy and the traditional agencies followed me”, he says. This time, the consultant took the medal for the triumph at the polls, but two people from the team that led the official “Against” campaign, in which all the right-wing parties participated, denied to this journalistic alliance that Cerimedo had any involvement. One does not know him and the other says that his name “is always going around”, but that he “works very much from the guerrilla of the networks”.

After the electoral triumph of the “Against” vote, La Derecha Diario did its own thing: it spread a news item indicating that President Boric had had a “nervous breakdown” after the electoral defeat. The Chilean government denied the fact and so did several information checkers, but the rumor was exploited by militants of the ultra-right. An analysis of social networks byChilean organization Interpreta, an ally in this journalistic investigation, detected that the hashtag #Boricinternado (Boric hospitalized) was already moving minutes before the news was published on the site.

His leap to the right

The pandemic found Cerimedo in Zoom meetings with Patricia Bullrich, former minister of Mauricio Macri, who at that time was contemplating running for congress in Argentina for the 2021 elections. “He is a snake charmer. A great swindler who sells half-truths that are impossible to verify. For example: he told us that he worked for (Donald) Trump’s campaign, but this is so broad that we are never going to be able to know. He also said that he had thousands of databases, but he never showed us anything,” said a person present in some of those online meetings. “When Bullrich decided not to be a candidate for congresswoman, he got angry, said we had no thirst for power and disappeared.”

Cerimedo replied with the same vehemence: “it is the worst team I worked with. Patricia is a fan of trolls and they spent a lot of money in companies that supplied them. I left because of that kind of thing”.

The pandemic was also a good time for politics. La Derecha Diario was attacking the Argentine government for applying strict sanitary policies different from the relaxed ones Bolsonaro wanted to impose in Brazil. In times of doubt about the coronavirus, Cerimedo’s site spread disinformation related to Covid, a recipe used by the right in several countries during this period. They published that the Argentinean state entity in charge of approving the vaccines had confirmed that the doses contained graphene, a harmful substance, but this was later verified as a lie by Chequeado.

The last elections in Brazil would make his turn to the right more blatant. Cerimedo was Eduardo Bolsonaro’s host in an official trip to Buenos Aires last October, after his father’s defeat against Lula da Silva in the first round. La Derecha Diario broadcastedBolsonaro’s son’s tours, which showed Argentines complaining about inflation and other economic problems. In one of them, Eduardo enters a supermarket, opens an empty refrigerator and says: “that’s what socialism does”, a reference to the fake news about supermarkets being out of stock in Argentina.

“I don’t agree with that kind of thing, but that is not fake news. At that time there was a shortage of meat because there were no prices due to inflation. Eduardo used it to campaign. But disinformation is something else”, Cerimedo argues in the interview. The consultant took advantage of the last hours of Bolsonaro’s son in Buenos Aires to organize a breakfast with Javier Milei, his new client, the leader of the Argentine “libertarians” (see more details in the story by this journalistic alliance “Eduardo Bolsonaro traveled on official mission to meet with Argentine who lied about ballot boxes”).

Cerimedo was key in that proselytizing trip to Buenos Aires, although he had chosen to have a secondary role before the cameras. But that changed after Bolsonaro’s defeat in the second round, when the Argentine called a “live” on YouTube on November 4, 2022, to broadcast a study that had been shared with him by private entities about alleged fraud in Brazil. The live broadcast, entitled “Brazil was stolen”, was shared by pro-Bolsonaro politicians and influencers during a heated post-electoral climate in Brazil that led to the coup attacks on January 8.

The Argentinean spread false information about the electoral system during his live broadcast, which he later repeated in a public hearing before the Senate called by an allied legislator, as verified by Agência Lupa, Aos Fatos, EFE, AFP and Estadão. Following that video, the profiles of La Derecha Diario Brasil on Twitter, Instagram and Telegram were suspended by the Superior Electoral Court for spreading lies about the Brazilian electoral system.

“It was judicially proven that I did not spread disinformation. They suspended my accounts in November and unblocked me when January 8 happened because they found that I was not responsible,” Cerimedo argues in the interview. “I never said there had been fraud in Brazil, but that it had to be investigated”, he argues despite the evidence. And he adds that the blocking of the accounts had been a temporary measure.

As we were able to verify, La Derecha Diario’s accounts remain blocked in Brazil at the closing of this edition.

In addition, two statements issued by the TSE contradict him. The court stated last November 9 that “contrary to what [Cerimedo] said, it is not true that the previous models of electronic voting machines were not submitted to auditing and inspection procedures”. Days later, the TSE published another note about Cerimedo: “in a new live broadcast, carried out on December 11, an Argentine channel again questioned the result of the ballot boxes and spread lies about the Brazilian elections”. Despite the sanctions, his expertise in misleading has made Cerimedo the go-to guy of the right wing in South America.

The lion’s keeper

“My wife is a fan of Milei and always insisted that I had to meet him,” he recalls. Things moved quickly, because only a few months later Cerimedo was appointed head of communications for Milei’s presidential campaign. What’s more, he was put in charge of overseeing the whole party, taking care of votes both at the polls and in the digital world. “I work for Milei for free. Today I could ask for any number I want, but Javier could not pay me even if I charged him little. The campaign does not have those resources.” Congressman Milei has already designed his character: he calls himself “the lion” because of his whiskered mane, a histrionic economist who accuses “the caste”, the Kirchnerist and Macrista political leadership, to position himself as an outsider, the formula that proved successful for Bolsonaro four years ago.

A spokesman for Milei defined Cerimedo as “a worker” and told this alliance that they do not find ethical problems having him in their team because the accusations against him are unfounded. He accused leftist groups in Chile, such as Acción Antifascita(Antifa), of damaging his reputation and assured that the sanctioned accounts in Brazil were not his but those of homonyms, despite the evidence already presented by the TSE of that country.

Cerimedo says he can work for free because he does not live off politics. His business group makes profits from his private activities, he clarifies. His main source of funding are corporate clients of his advertising agency, complemented by the earnings of the Numen Academy, a space that offers online training courses in political marketing, community management and cybersecurity, among others. “Today politics represents 10% of my income”. This journalistic alliance could not verify this data because none of his five main companies have submitted balance sheets to the General Inspectorate of Justice. Four of these companies, being limited liability companies, are not required by law to file balance sheets. However, one of these is a corporation that is required to do so and has not. When questioned on this matter, Cerimedo assures that all his accounts were submitted in due time and form.

“Come and train as a leader to make Argentina great again!”, invites the web page of the School of Political Leadership, another of Cerimedo’s ventures. Milei is a teacher there and lectures on the subject “Argentina and economic growth”. The consultant is also a teacher, lecturing on “Electoral Campaign”. The director of this space called “Ciudadanos” is Camila Duro, Milei’sparliamentary advisor. People looking to sign up from abroad to take the course online must pay 25 dollars.

With the electoral campaign already starting in Argentina, Cerimedo has placed electoral advertising on Google, aimed atprovinces where Milei’s party, La Libertad Avanza, is running candidates. He also held, he says, long meetings in Meta’s offices in Buenos Aires, but he is not listed as an advertiser with the network. This new liberal party, almost without territorial structure, sustains the diffusion of its message through social networks. Cerimedo’s aim is focused on absorbing social discontent to get Milei into the second round of the Argentinean elections.

Cerimedo looks to next year’s U.S. elections as the next step in his career. La Derecha Diario covers what happens in that countrywith constant interest. It replicated the story known as “the big lie” about alleged fraud in the 2022 elections, denounced by supporters of former President Donald Trump, although dozens of state officials and local judges had not found a single piece of evidence. It was a Trumpist political strategy to weaken faith in an institution central to democracy, as reiterated by several analysts. They also spread disinformation about Latino migration to the United States and even about President Joe Biden’s health.

Cerimedo, of course, is betting on a Republican win in 2024. He tweeted a photo in March with an adviser to Trump’s former defense secretary. “Great breakfast meeting. Great things are coming these next few years,” he wrote. Always willing to talk to this journalistic alliance, Cerimedo chose silence for the first time when asked about him possibly working for the founder of American populism. “I can’t share that information,” he replied. Perhaps this is what’s next for Cerimedo, the electoral consultant of the new Latin American right that is willing to lie in order to win.

Mercenarios digitales es una investigación de Chequeado (Argentina), UOL y Agência Pública

(Brasil), LaBot (Chile), Colombiacheck y Cuestión Pública (Colombia), CRHoy,

Interferencia y Lado B (Costa Rica), GK (Ecuador), Factchequeado (EEUU) Ocote

(Guatemala), Contracorriente (Honduras), Animal Político

y Mexicanos Contra la Corrupción y la Impunidad (México), Confidencial y República 18

(Nicaragua), Ojo Público (Perú), El Surti (Paraguay), La Diaria (Uruguay) y tres

periodistas investigativas (Bolivia y España/Colombia); las organizaciones de

investigación digital Cazadores de Fake News (Venezuela), Fundación Karisma

(Colombia), Interpreta Lab (Chile), Lab Ciudadano (Honduras) y DRFLab (EEUU);

y estudiantes del curso de maestría Using Data to Investigate Across Borders de la profesora Giannina Segnini (Universidad de Columbia EEUU), con la coordinación del Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística, CLIP. Revisión y asesoría legal: El Veinte.

Con apoyo financiero de Free Press Unlimited, el programa Redes contra el silencio (ASDI), Seattle International Foundation y Rockefeller Brothers Foundation.