On Tuesday, January 31, at the Soto Cano air base, Arnaldo Urbina Soto, the former mayor of Yoro municipality, was handed over to the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) for extradition to the United States.

Soto will face trial in the US on charges related to drug trafficking. His extradition brings the number of Hondurans extradited to the United States on such charges to 36, including former president Juan Orlando Hernández.

Almost a year after the capture of Hernández on February 15, 2022, Contracorriente opens our photographic archive to tell the story of the extraditions from Honduras that have earned the country the label of ‘narco-state’.

Text and photography: Jorge Cabrera

Edited by Celia Pousset and Jennifer Avila

Cover art by Daniel Fonseca

Translated by Ann Louise Deslandes

In the last decade, extraditions from Honduras to the US have included prominent politicians, the process carrying the hopes of the population that justice, albeit in another country, can come to those who turned Honduras into a narco-state.

As a photojournalist, my work has been to illustrate the challenges, struggles, joys and frustration faced by those of us who live in this country. I do this by looking through a camera lens, capturing the big picture and the small details of our society.

The challenges of bringing those images to the Honduran people – for whom they are a beacon of hope – are enormous. For example, in covering the extradition of Carlos Arnoldo Lobo, alias ‘El Negro’, ten years ago, I waited for hours in position up a tree on the Chiminike Interactive Teaching Center grounds to get a photograph of the captured drug trafficker.

On March 27, 2014, ‘El Negro’ Lobo was arrested in an exclusive area of San Pedro Sula, while traveling in a luxury van. On May 9 of that year, Honduras extradited him to the United States.

The extradition request was raised through a bilateral extradition treaty that has existed between the United States and Honduras since 1909, but which only became effective through a constitutional reform in 2012 that allowed the surrender of Honduran citizens accused of drug trafficking, money laundering and terrorism. Previously, Article 102 held that “no Honduran may be expatriated or handed over by the authorities to a Foreign State”.

On December 9, 2014, federal judge Darrin Gayles sentenced ‘El Negro’ Lobo to 20 years in prison. However, that same judge modified his sentence and reduced it by 50%, so Lobo could regain his freedom in August 2023. That case opened a Pandora’s Box, with many more extradition requests being made along with wide media coverage.

Covering extradition has not always been difficult. Those involved are almost always presented to the media.

Miguel Arnulfo Valle Valle and his brothers Luis Alonso and José Inocente, were presented to the media at the National Police headquarters in Tegucigalpa on October 5, 2014. The Valle Valles became the cartel that controlled drug traffic through the Honduras-Guatemala border territories en route to the United States.

The brothers were captured in a police operation in Copan in western Honduras. The operation was carried out by the then chief of police, Ramón Sabillón, who was later removed from his post and went into exile to save his life. Sabillón returned to Honduras when Xiomara Castro won the elections in November 2021 and is now the security minister.

Within the profession, covering extraditions is sometimes a competition for the exclusive photo.

It is a ritual among photojournalists: we all arrive as early as possible to get the best spot; we measure the space, the light, the angle. We talk to each other so as not to get in each other’s way before each event and, despite the competition, there is camaraderie. When the action starts, cameramen and photographers run to get to the key point, tripods fly, there are blows, shouts and insults. The police try to control the thrusting of elbows and lenses and, for a moment, it seems impossible to do so until suddenly that fleeting moment arrives, the second of bated breath in which the captured character is in front of us, for us to capture with our cameras.

2014 was a year full of extraditions. The media had to wait until nightfall for the arrival of Juving Alexander Peralta, who was escorted by police officers to the Supreme Court of Justice on September 10 of that year. Peralta was charged with drug trafficking in the United States and captured near the coastal city of La Ceiba, 185 km north of the capital, Tegucigalpa.

Special security teams transferred Juving Peralta under strict security measures to Tegucigalpa and he was held in a maximum security cell at the National Police Special Forces ‘Cobras’ facility. He was initially sentenced to 17 years in prison in the United States, but made accords with the Attorney General’s Office and agreed to cooperate. He is currently on parole after being released from prison in February 2022.

Héctor Emilio Fernández Rosa, alias ‘Don H,’ was another of those extradited that year. He was presented to the media on October 7, a few days after that of the Valle Valle brothers. Fernández Rosa, another Honduran drug trafficker responsible for transporting cocaine to the United States, was arrested in an operation carried out by special forces of the Honduran police with the support of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in the El Hatillo neighborhood, north of the capital.

‘Don H’ was 48 years old when he was captured. He operated in Copan along with the Valle Valle family and until 1998 was in charge of receiving and transporting cocaine from Colombia to Honduras. From Honduras the product would be delivered to Guatemala where it continued on its way to the United States. In August 2019, when ‘Don H’ learned that he would be sentenced to life in prison, his defense appealed, arguing that procedural errors had been made in the trial when calculating the sentence. The appeal was denied in June 2021.

There were rumors that ‘Don H’ had paid millions of dollars in bribes to officials in 2006, including a former Honduran president, in order to “ensure the passage of drugs to the United States,” which was denied by former President Manuel Zelaya Rosales (2006-2009), now a presidential advisor to his wife, President Xiomara Castro.

The day ‘Don H’ was presented we had to wait at the Special Forces soccer field. For some reason, a high command officer had invited some colleagues to play soccer, “but without a ball” because the officer who had organized the game never arrived.

The fall of former President Juan Orlando Hernández

As I have said, photographing extradited people is full of challenges and adrenaline. The most shocking extradition – so far – was that of former president Juan Orlando Hernández, whom I had photographed so many times when he was in office.

Before his capture and extradition, it was already publicly known that Hernández was being investigated as a co-conspirator and then as the principal drug trafficker in a drug and arms trafficking network that implicated the Honduran political class – and even members of the economic elite – in a world of illegal markets. His brother, former National Party congressman Antonio Hernández, was not extradited, but was captured in the United States. He was the piece that toppled the domino line that also brought down former President Juan Orlando Hernandez. After the November 2021 elections, people celebrated Xiomara Castro’s win, but they celebrated even more that ‘JOH’ was going to New York, as the song goes.

His extradition occurred on April 21, 2022, 66 days after he was captured at his residence in Tegucigalpa on February 15, 2022. It had been more than two months of waiting for the Honduran people who had just elected a new President, the first woman President in the history of the country. The new government held great expectations among Hondurans after twelve years under the authoritarian and illegitimate mandate of Juan Orlando Hernandez.

The day of his capture, I remember running past the entrance of the residence before the security checkpoint was installed around the house of the former president, which is located in one of those gated communities that seem to be from another world, shielded from the poverty and inequality that surrounds them. I needed to be as close as possible to his house – all the media had thus objective, to get closer, but only four people managed to get there.

We waited all night under a security booth at the house of the ex-minister and deceased sister of JOH, Hilda Rosario Hernández. It was a cold and rainy night. We could not eat because if we left the police fence we could not enter again. Our senses were fixed on one single objective, to obtain the images of the moment when the former president was taken out. The national and international media were waiting for them, but the people in Honduras were waiting for them even more.

The night and early morning passed and the former president did not leave his house. The next morning, hungry and cold, we received, as if from heaven, some baleadas that a neighbor in the area gave us as a gift, a good Samaritan who had seen us since the night before. We were trying to charge our cell phone batteries since we had to report what was happening inside and we were the only ones who could do it.

Later in the morning, the police tried to remove us, but we managed to stay after convincing them that it was our duty to be there to report what was happening, as people were not going to believe anything until they saw the photographs and videos. The police even removed the military personnel who were guarding the Hernández house, the atmosphere was charged with distrust. It is said that a picture says more than a thousand words; it is true, especially when it comes to showing an ex-president captured to be extradited, the image makes it all real in the eyes of a people hurt by the abuses of their rulers. “There he is, I saw him in the photo” – so goes the ethical responsibility that weighs on the shoulders of us photojournalists.

At two o’clock in the afternoon, after more than 24 hours without enough sleep or food and under the command of the police, an operation was carried out and several armored vans arrived and the police covered the whole picture, the police opened two vehicular roads and an aerial one to throw the media off the scent – total chaos. I ran to the exit of the residential area, a marathon of 4 streets, loaded up with a backpack and cameras. When I got to where the media melee was, I got into the first van I could – it belonged to a well-known journalist. I jumped in the back – the paila, as we say in Honduras – and we started to follow one of the caravans. People could be seen in the streets shouting with joy at the capture, but my job was to catch up with the caravan.

Everything was very fast, there was no time for anything else. We got the photos of the moment the special forces arrived, and then we were taken away by the special forces. My photos of this capture went all over the media. I had done it – I thought. Little did I know that this was the beginning of the longest 66 days of my career waiting for extradition.

Together with other colleagues from the international media, we decided to rent a room near the National Police’s ‘Cobra’ special forces’ facilities where the former president was being held. We called this room ‘the bunker’. Its walls were pastel green and the floor was bean red, there was a tiny living room and, the crown jewel, a balcony. It was tiny too, but that little balcony was the reason that room was chosen. It gave us a privileged view of the police facilities and would allow us to keep an eye on all the movements and run wherever we needed to go to get the perfect picture. Organizing ourselves, we managed to get room for five people to sleep on mattresses on the floor.

The days went by and we had to divide the balcony into day and night shifts. We shared the expenses for food shopping and once we had to ask for a cistern with water because we didn’t even have enough to wash a dish. It was then that we started to share space with the new neighbors in the other rooms, mostly policemen who lived near their work in the Cobra facilities. We met many times; policemen and journalists, each one doing his job – for a while, thus, we shared our daily life. All to get an image. The day after we began to live in that state of alert, several media outlets did the same and very soon the surroundings were filled with television cameras.

Cameras were fixed on their tripods waiting to capture a clean image of the former president walking or moving around the facilities. Every day we saw members of the DEA come and go, but never the ex-president. We recorded every movement inside and speculated when we captured images, thinking it was JOH.

In the end, the wait paid off. From our little balcony, we saw a person running through the pool area of the Special Forces facilities, guarded by a Cobra agent. It was the former president taking his hour of sports and sun, wearing a blue cap, black shorts and yellow shirt.

After the dissemination of this image, media outlets rushed and filled the place where we had been waiting for days. But, even though all the cameras were ready to shoot, we never saw JOH walking again like that day.

On March 20, 2022, the rumor circulated that JOH was going to be extradited. Patrol cars sounded their sirens, police officers ran from one side to the other, helicopters could be seen flying over the facilities. In the distance, the heliport was guarded by the Cobras and a white Prado van was already waiting. Among those of us covering the event we were tense, saying, “this is going to happen”, “get ready for the extradition”. But it didn’t happen, it was all a simulation on the part of the Security Department. That night nobody slept.

The following days became even more tense as the Police had created perimeters that we had to resist in order not to be removed. In every conversation we speculated something different about what would happen. We made maps in our minds to the final result of our coverage.

Then came the long-awaited day, April 21, 2022. Honduras was waiting for an image of the extradited ex-president. All the media were called to enter the Special Forces to look for the best position; I do not know how many of us were there but I can say that we could not fit in that place, we were cramped and anxious. Suddenly a man in the center of the police guard with a blue jacket and blue pants was seen walking as if he did not hear the uproar of all the journalists shouting for their comments to be shown on their respective television channels. Every step was transmitted, every gesture, looking for an expression in the midst of their indifferent attitude.

The dust raised by the helicopter covered us, blurring the lenses of the cameras, but no one stopped, the protocol was broken and we all ran after the president, the special forces police intercepted me and beat me to make me back up. I’m not saying I didn’t feel the blows, of course I felt them, but on top of that, at that moment, my camera was an extension of my senses, of my whole body, my only focus was the guy in the blue sweatshirt, so I kept going.

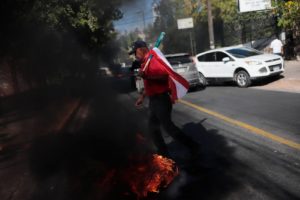

Once Hernández was secured, the helicopter left with such speed that I decided to run to my motorcycle to try to get to the Hernán Acosta Mejía air base where the ex-president would be handed over to the DEA. I did not manage to get in, but my mind was already calm, I got the picture, it was worth it. I went to Toncontin square, where the international airport used to be, there was a lot of noise, printed memes adorned the metal nets that separated the demonstrators from the plane where the unpopular ex-president was being flown to the United States. Those celebrating the moment shouted the slogan “JOH Out”.

In my more than 22 years as a photojournalist I have covered different situations, but never the extradition of an ex-president, and if you wonder what is the most difficult thing to do in this work that we lovers of the frozen image do, I have a clear answer: Time. If I persisted I would achieve it, if I achieved it my mind would be calm; it is a single objective, to get the photograph that has taken me the longest time to obtain.

The formal extradition indictment describes that between 2004 and 2022, Hernández participated in a corrupt and violent drug trafficking conspiracy to facilitate the importation of hundreds of thousands of kilograms of cocaine into the United States. He is accused of receiving millions of dollars to finance his political campaigns and of using his public office and security forces to support drug trafficking organizations in Honduras.

According to the indictment, Juan Orlando Hernández protected some of Latin America’s biggest drug traffickers, including his brother – and former member of Honduras’ National Congress for the National Party – ‘Tony’ Hernández, who is currently serving a life sentence in the United States for drug trafficking-related crimes.

The indictment states that the former president also provided confidential military and police information to drug traffickers to help them move tons of cocaine through Honduras and ordered the shipments to be protected by members of the National Police.

The new wave of extraditions

When Sabillón took over his position as Security Minister in 2022, he told Contracorriente in an interview that a main focus of the National Police in the new government would be to execute all pending extradition requests. Many of these have been blocked by the Honduran justice system itself, as in order for a person to be extradited they must not have open cases in the national justice system and, in addition, the Supreme Court of Justice must approve the extradition process through the appointment of a judge. All this must be done before the national police can capture and put any accused person on the plane.

After Hernández’s extradition came the memorable extradition of Juan Carlos ‘El Tigre’ Bonilla, former director of the Honduran National Police between 2012 and 2013 during the Porfirio Lobo administration (2010-2014).

Bonilla was charged in April 2020 with participating in conspiracy to import cocaine into the United States and was requested for extradition in May 2021 by the Southern District Court of New York.

When I became aware of the arrest of the former director of the National Police, my first reaction was to move to the Special Forces facilities. By the time I arrived there were already at least ten media outlets reporting. My cell phone kept receiving images of the moment Bonilla was captured at the Zambrano toll booth, 45 km from Tegucigalpa. I decided to wait there. Once again my colleagues and I saw each other’s faces and we commented that we would have to activate the ‘bunker’ again.

But everything suddenly changed. The Secretary of Security summoned us to El Ocotal, the offices of Ramón Sabillón, Minister of Security. It was 5 pm, which meant that the traffic in the city, as always, was going to be heavy. I was glad because I had taken my motorcycle with me that day, so I set off for the place. Night fell and once again the photojournalist’s ritual began: standing at the gate of the National Police convention center waiting to enter, one on top of the other, knowing that we had to pass through a narrow, half-opened gate.

Once inside the facilities, we found El Tigre sitting on a chair surrounded by special police. His gaze did not express fear despite the shackles he wore on his hands and feet. It was a strange sensation since the person they were exposing to the media was someone feared by all those behind him, who were also police officers.

After his capture on March 9, 2022, Bonilla was held in a cell in the First Infantry Battalion, located on the outskirts of the Honduran capital. His extradition was approved by a judge in Tegucigalpa on April 8 of that year and on May 10 he was taken to the Hernan Acosta Bonilla Air Base on the southern edge of the Honduran capital for extradition.

The extradition of Herlinda Bobadilla followed on July 26, 2022. Bobadilla was sought by the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia for the crime of conspiracy to bring non-controlled substances into the United States.

Bobadilla was arrested on May 15, 2022 in a mountain in the department of Colón. That same day she appeared at the first hearing before the extradition judge and was placed under provisional arrest at the Cobras barracks. She appeared to be a very humble woman, the sorrow could be seen in her eyes. On July 26 of that year she was transferred to the Honduran Air Force located at the Hernan Acosta Mejia military base by a police caravan. At least 70 police officers and 16 vehicles of the National Police were deployed for the transfer and subsequent extradition of the Honduran woman requested by the US Court. It was a contingent almost as large as the one used in the extradition of Juan Orlando Hernández.

Herlinda was considered the leader of the Montes Bobadilla clan, accused of controlling the Honduran Caribbean area where, through her links with drug cartels in Colombia and Mexico, they had managed to ship thousands of kilos of cocaine to the United States.

In case anyone wonders how extraditions work, I will try to explain, although I may be missing something. In general, the procedure is that the extradition order is sent from the U.S. State Department to the Honduran Foreign Ministry, which in turn forwards it to the Supreme Court, which must appoint a special judge who must verify that the documentation received from the United States meets the requirements of the law. Let us remember that this can be done with the accused already arrested or while he is being captured.

And so the extraditions continued. Michael Powery Wood, alias ‘El Caracol’ was captured on August 7, 2022 in Islas de la Bahia, in the Honduran Caribbean. Powery Wood will face trial in the United States for “conspiracy to manufacture and distribute five kilograms of cocaine with the intent and knowledge to believe that it would be illegally imported into the United States”.

We were summoned on January 27, 2023 at 6 a.m. at Hernan Acosta Mejia Air Base to report the extradition of El Caracol. But, with nothing being set in stone in this journalistic work, the DEA plane was delayed and had not landed at the air base so we had to wait, again. The journalists were watching an application on their phones that showed them the point where the plane that would have to take the person to be extradited was located, it was then when many of them, as good air traffic controllers, estimated the distance remaining for the landing. And confirming the calculations of their colleagues, at 10 o’clock in the morning the plane landed and began the delivery of the capture. It was fast, the adrenaline of the previous extraditions was not felt.

There has been so much coverage of extradited persons, that one begins to normalize the situation, when on the contrary, each one of them should shock us because it evidences the dysfunction of our justice system and the depth that the roots of drug trafficking have reached in our society and political system.

We come to the last one; better said, the most recently extradited for now. Arnaldo Urbina Soto was extradited on January 31, 2023. Due to the risk of a possible escape, the Special Forces made the extradition transfer on the runway of the Soto Cano air base in Comayagua. The former mayor of Yoro, dressed in white overalls – due to the risk of Covid-19 infection – passed from the hands of the Honduran authorities to those of the DEA agents. The detainee, who had already tried to escape from the Támara prison in November 2022 to escape extradition, spent his last months in Honduras in the cells of the First Infantry Battalion located in the village of Mateo in the department of Francisco Morazán.

Soto Urbina was sought by the Southern District Court of New York in June 2018 on charges related to drug trafficking and carrying weapons between 2005 and 2014.

U.S. Attorney Geoffrey S. Berman and DEA agent Raymond P. Donovan, filed an indictment against Arnaldo Urbina Soto and his brothers, Carlos Fernando Urbina Soto and Miguel Angel Urbina Soto. The indictment states that the brothers “took advantage of their power in Yoro and allied with other criminal organizations, such as Los Cachiros and Los Valle Valle, to receive cocaine shipments sent by small planes from different parts of the country, using clandestine airstrips and roads around Yoro.”

It is also noted that Soto Urbina and his brothers coordinated and formed part of heavily armed groups to monitor drug transfers and unloadings. In June 2019, a Natural Judge of the Supreme Court of Justice granted the extradition after examining the request and conducting an evidentiary evaluation hearing. However, the procedure for extradition of Honduran nationals, established by an ‘Auto-Accord’ of the Supreme Court of Justice in 2013, requires that the requested person has no pending charges domestically. Which was not the case for Urbina Soto until the end of 2022.

Indeed, in 2017 he was convicted for the crime of money laundering to the detriment of the economy of the State of Honduras and, in 2020, he was sentenced to 16 years of imprisonment. But recently, on December 15, 2022, the Criminal Chamber of the Supreme Court of Justice unanimously declared the appeal filed by Urbina Soto’s defense to be admissible. The criminal chamber applied the retroactivity of the law after the reform of the Money Laundering Law, so Urbina was acquitted of this crime and the way for his extradition was opened .

Part of my job before an extradition is to find out where the person will be transferred from and it has always been from the battalion or the Special Forces. A day before Soto Urbina’s extradition I had tried to get solid data, but nobody knew anything or, to be clear, I did not know anything. I asked a journalist colleague if she could get the data for me. My colleague was told that there would be no access for the media. I could not be calm, so I stayed as close as possible to the base where the Hondurans requested by the United States have always been delivered. At 9 a.m. that morning, I received a message on my phone saying that everything was going to happen in Palmerola, where the new international airport and the still active U.S. military base are located. It was a strange, things almost never happen that way. Access to the U.S. military base is difficult so for a moment I thought I was not going to be able to cover it. But we all have bosses and I am no exception, I had to do my job, not doing it is not an option – it includes that you who read us, see in pictures what is happening in Honduras. So I took my car and went to the Palmerola base in Comayagua. I entered quickly but once again we had to wait because of the delay of the DEA plane. Once the plane arrived, Urbina was already waiting in a white Prado. Minutes later, he could be seen walking in white overalls among the police escort.

This is not over, the extraditions will continue and so will the coverage. The next extradition is that of former congressman Midence Oquelí Martínez Turcios, who is wanted by the Southern District Court of New York for crimes related to arms and illegal drug trafficking. He was captured in December 2022 in the department of Colón, after being a fugitive from justice since 2018. Martínez Turcios, was deputy of the Liberal party for the department of Colón during two terms, from 2010 to 2018. Colón, the birthplace of the criminal organization Los Cachiros, also imprisoned in the United States. On January 17, 2023, a Supreme Court of Justice judge granted the extradition request.

According to the police commissioner and Special Forces director , Miguel Perez Suazo, there are 27 arrest warrants to be executed, which means that our work on this issue is not finished. One might think that the high-impact extradition of Juan Orlando Hernández made this coverage exceptional. But they all are. In the end, at one end of the camera is the extradited person, someone who has surely done a lot of damage to this country, and at the other end is me, someone who, like my colleagues, lives day by day the consequences of the acts of those people whose photos and videos become the memory of this country, that hopefully one day will lose the label of ‘narco-state’.

I cannot know what the circumstances will be, but I will be reporting on that along with colleagues from other media – hopefully calmly or again negotiating elbows and flying tripods. Nothing personal, just part of the ritual of the trade. What I do know is that we all go with the same objective, the image, and in the end, despite all the adversities, we will say goodbye knowing that another extradition is on its way.