Lideni is a Lenca person; one of the main Indigenous peoples of Honduras. A young girl, Lideni and her family were not allowed to return to their home in Tierras del Padre after her mother was issued a restraining order. Lideni eventually returned, but three attempts at eviction have made her fearful of losing her land, gardens, crops, and friends all over again. This story was co-produced by Agenda Propia and Contracorriente.

By Persy Cabrera and Luis Lezama

Photos: Fernando Destephen and Persy Cabrera

Video: Persy Cabrera and SentARTE

Lideni, Eliezer, and their cousins all begin to whistle. “They’re summoning the wind, it’ll come soon,” said their mother, Yessenia.

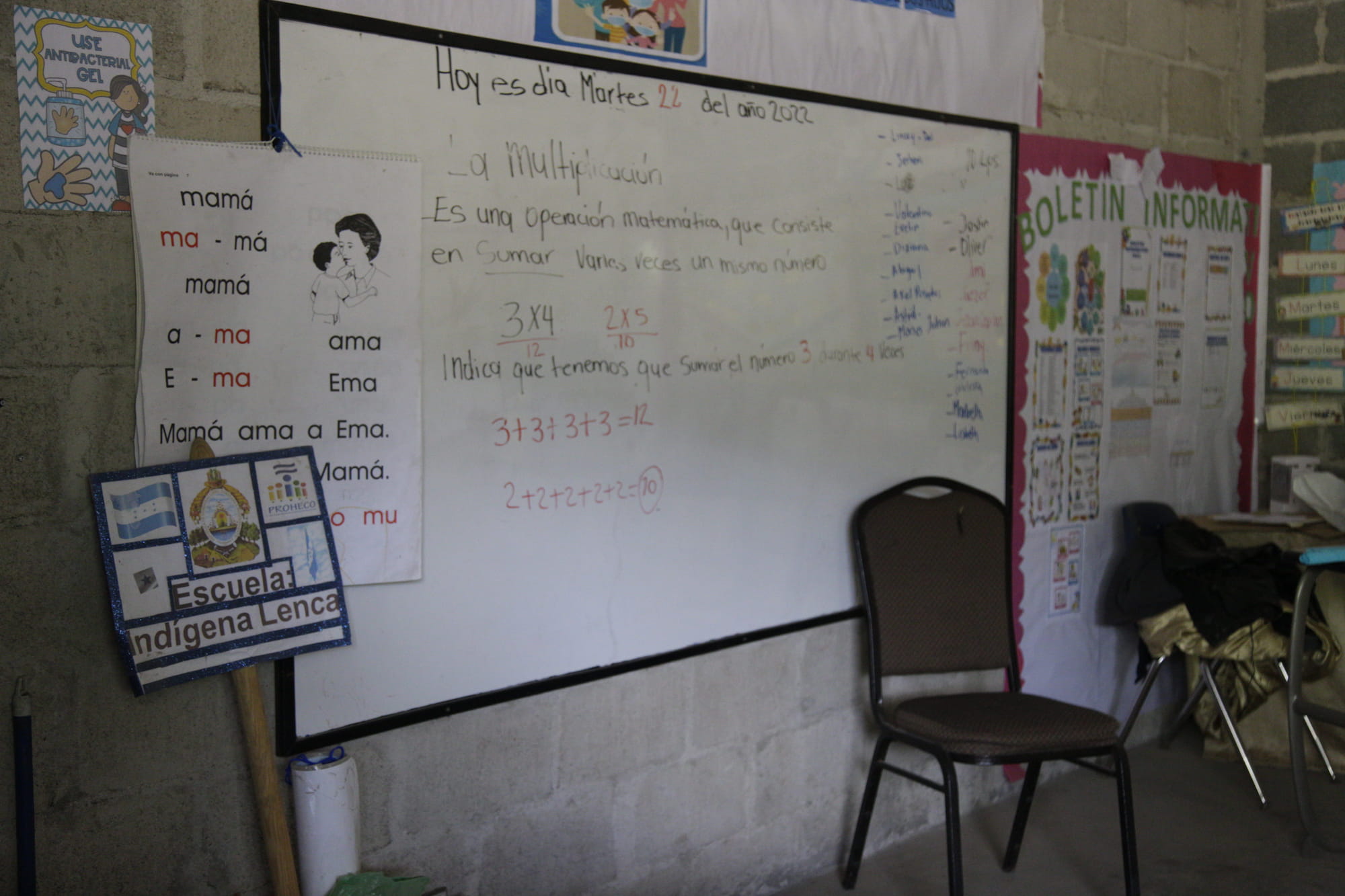

Within seconds, a gust of wind rustles through the pine forest behind the elementary school in Tierras del Padre. It’s a community of Indigenous Lenca people about an hour’s drive from Tegucigalpa, the capital of Honduras.

When she was only nine years old, Lideni Alonzo was forced to leave relatives and friends in Tierras del Padre, where if she wanted a mango, she would climb a nearby tree. She and her younger brother, Eliezer, would reminisce about that mango tree when they fled their community to Tegucigalpa. When asked if she made any friends during her two years in the city, Lideni scoffs, “Friends? Enemies are more like it.”

Near the house where Lideni and Eliezer lived in Tegucigalpa was another mango tree, but the neighborhood children didn’t want to share the fruit. Even though one of the adults in the neighborhood gave them permission to pick mangos, the local children said Lideni and Eliezer were thieves, so they decided not to. They couldn’t seem to enjoy the fruit anymore because it made them think of home.

The two children were forced to leave Tierras del Padre in 2017, when a Honduran court issued a restraining order to their mother, Yessenia Posadas, a Lenca school teacher who was prosecuted along with 11 others from the same community for land usurpation. They were all ordered to leave their land and homes.

The Lenca Indigenous people have lived in parts of Honduras and El Salvador since pre-Columbian times. They have been subjected to a steady process of cultural assimilation by multiracial people. According to a 2001 study by the Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences (Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales – FLACSO), this assimilation has resulted in the loss of their native language and the dissipation of many traits and customs due to direct and indirect discrimination, human rights violations, and the privatization of ancestral lands.

The Lenca struggle is symbolized by Lempira, a Lenca chieftain from the 16th century who died resisting the Spanish invasion and became a Honduran hero. The national currency and one of the country’s departments are named after him.

Five centuries after Lempira’s death, the sword and the cross no longer threaten Tierras del Padre. Instead, it’s an aptly named real estate company: Inmobiliaria Siglo XXI (Century 21 Real Estate).

It was on Lideni’s seventh birthday – September 18, 2017 – that Yessenia received the restraining order. “I couldn’t enjoy my birthday because we were busy moving our belongings,” said Lideni.

Yessenia was a teacher at the Lenca Indigenous Education Center in Tierras del Padre and taught the Lenca language to approximately 70 children, including her own three children. But all this came to an end when she was prosecuted for land usurpation and issued a restraining order, forcing her out of her home and school.

Yessenia is known in her community for being the driving force behind the school’s creation and for teaching the Lenca language, which is almost extinct. The school is a crucial factor in teaching future generations the Lenca language and culture. It’s also the most readily available educational provider for an ethnic group that has a 17% illiteracy rate, according to a 2013 census conducted by the National Institute of Statistics (Instituto Nacional de Estadística – INE). Illiteracy worsened in Honduras during the COVID-19 pandemic since much of the population didn’t have access to the Internet and remote learning technology.

“Our language is being extinguished,” said Yessenia, “and this has been going on since colonial times. Anytime we try to get ahead, we are persecuted and evicted. We’re just trying to protect what little we have, and what happens? Persecution and prosecution.”

The court order forced her to quit her teaching job and move to Tegucigalpa with her three children on September 18, 2018. Once a month, Yessenia had to appear in court and sign a statement proving that she hadn’t left the country. The day they arrived in the city, the family slept in the central plaza, in front of the statue of General Francisco Morazán and the cathedral. “We had nowhere to go, and it was already dark,” she said.

Lideni remembers a shopping mall in the city she liked but didn’t enjoy much else about Tegucigalpa because there was nothing to do except sit in front of a television. She talks much more fondly about her community, their chickens and livestock, running through the forests, hunting for mangos, and tending the garden with her family in Tierras del Padre.

But the forest, the mango trees, and the garden are part of the 10,000 hectares claimed by Inmobiliaria Siglo XXI, and for which Yessenia and 10 other people from the community are being prosecuted for resisting eviction by the police. According to Pedro Lagos, president of the Lenca Indigenous Council of Tierras del Padre, the court has ordered three evictions of about 120 families from Tierras del Padre.

The final eviction attempt happened on February 9, 2022. Media coverage showed the villagers resisting the eviction as their children sang the Honduran national anthem in the Lenca language. When the dramatic images of the eviction were broadcast, inconsistencies in the eviction order were revealed and it was canceled.

Lideni told us Eliezer was among the children who sang the national anthem. In addition to Lenca, they also know a few words in English, thanks to their teacher and mother, Yessenia. “Their mommy is trilingual,” laughs Yessenia.

Yessenia locked herself and her children inside their home that day. “We’re not leaving here,” she told herself. “I’ll only leave if the children are in danger.” They heard nothing for a while and decided to go to the main road where some Tierras del Padre residents were battling with the police. Lideni lamented the violence of February 9, “Our people were beaten, even some pregnant women.”

Honduras is a multicultural and multiethnic country, but ethnic groups have faced historical exclusion, marginalization, and discrimination, according to a 1999 report by the Inter-American Development Bank, Ethnic Poverty in Honduras. Nothing has changed since that report was issued and the Lencas of Tierras del Padre now have to endure a slow legal process conducted by government agencies that community leaders say are biased against them.

When presented with the eviction order on February 9, the people of Tierras del Padre noticed that it bore a 2021 execution date, so they quickly denounced the inconsistency to the media and the authorities. Pedro Lagos said that judge and Inmobiliaria Siglo XXI promptly corrected the error and within two hours, a new eviction order was presented to the residents of Tierra del Padre. However, the Lenca Indigenous Council took advantage of this respite to file two appeals with the Supreme Court that are still pending resolution.

With all the violence and insecurity in Honduras, inadequate protection of the country’s Indigenous peoples endangered the lives of Lideni and her family. During their two years away from home, they also lived for a time in Santa Ana, a municipality near Tierras del Padre. That’s where they were robbed by “more enemies,” said Lideni. “We shouldn’t have gone there because they stole our things.” The thieves took a stereo system, a DVD player, and a set of “brand new” pots and pans, according to Eliezer.

The entire experience was traumatic for her children, says Yessenia. They kept asking questions.

“Mommy, when are we going back?”

“Why did they take our house?”

“Why were the others allowed to stay, and we weren’t?”

As a mother and a teacher, she had always been able to answer their questions, but not anymore.

“I don’t know,” she would say.

Yessenia talks about the impacts of being forced to leave their community and thinks that the authorities don’t care about the economic and psychological damage to her family.

“The Honduran government thought that this was a simple restraining order,” she said, “but they didn’t think about everything that comes with it. That’s why I said a million dollars wouldn’t be enough to compensate for all the damage they have done to us and our children.”

But the dispute persists, and the people of Tierras del Padre continue to worry about more eviction attempts and restraining orders. The villagers have hired a lawyer that they pay with contributions from the entire community. They also have help from several NGOs that provide legal advice.

Land grabs

Inmobiliaria Siglo XXI wants to build houses on the disputed Tierra del Padre land. The real estate development company is headed by Mario Facussé, who belongs to one of the wealthiest families in Central America, according to a2017 report by the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC).

Facussé is disputing 10,000 hectares of land in Tierras del Padre he claims to have purchased from another company, Corporación Inmobiliaria de Inversiones. But Pedro Lagos says that these are Lencan ancestral lands and points to a property title issued in 1739 as proof. Facussé is accusing them of land invasion and says this is why the 11 people who resisted eviction are being prosecuted. Facussé has a supplementary title granted in 2013 to back him up and notes that the judge who heard the 1739 ancestral land title case was dismissed.

Not having property titles is a long-running problem for Honduras’ Indigenous peoples: the Pech, Tawahka, Miskitos, Tolupanes, Garifunas, and Lencas. According to areport by the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA), in 2010, only 10% of the Indigenous population in Honduras had land titles.

“We have been victims of pressure, humiliation, and military force,” said Hermes Posadas, Yessenia’s father and president of the Council of Elders. “They have attacked and tried to remove us by force at the behest of a landowner that the government supports. We are an Indigenous people and are only defending our property, nothing more. We just want to be left alone so we can work and farm our land.”

Like his daughter and grandchildren, Posadas was forced out of his community where he practiced natural medicine in an area that has no public health center. He is a community leader who is demanding that the ancestral title be accepted in court as legal proof of their rightful ownership of these lands.

“We dreamed of going home someday, and we did”

Despite their youth, the Alonzo siblings have had a tumultuous childhood marred by exile. Their experience parallels other Indigenous struggles in Honduras. Lideni and Eliezer remember spending four days with the Viva Berta! protestors that camped in front of the Supreme Court during the trial of David Castillo, who was convicted of the murder of environmentalist and Lenca Indigenous leader, Berta Cáceres.

“They held up posters about the man who killed Berta. And they handed out flyers that said, ‘Justice for Berta.’ Then the man came … I think his name was David,” said Lideni.

“David Castillo,” said Eliezer. “The day of the court decision, they built a bonfire and demanded that he be found guilty.”

On the day they were forced out of their home – the toughest day of their lives – the children left some belongings behind in hopes of returning someday. “We only took a few things with us because we dreamed of returning home someday, and we did,” said Lideni. This young girl shares the same hope that Berta Cáceres felt.Murdered in 2016 for opposing the government concessions to exploit the country’s rivers, Cáceres used to say, “When we started the fight against Agua Zarca [hydroelectric dam project], I knew it was going to be very hard. But I also knew we were going to prevail. The river told me so.”

The Lenca belief system is a mix of colonialist religion and pre-Hispanic beliefs. One of its fundamental tenets is an animist vision of reality. Carlos Brenes, in his report about the role of nature in Central America’s Indigenous communities (Programa de Árboles, Bosques y Comunidades Rurales en Memoria Taller Indígena Centroamericano) says that the biggest danger in the efforts to restore Indigenous knowledge is to fall into a rationalist trap that removes the ability to feel from its system of knowledge. This is the type of knowledge that comes from feeling, exemplified by Lideni, Eliezer, and their cousins whistling to the wind. It comes from their close relationship with nature in Tierras del Padre, where their families involve them in farming the land and where their school is committed to reclaiming their culture.

When asked if she knows why her mother had to leave Tierras del Padre, the undaunted Lideni doesn’t hesitate to say, “We left because my mom had a restraining order against her for defending our lands.”

Yessenia smiles as she hears this, privately proud that she has passed on this commitment to defending the Lenca’s ancestral lands. But maybe it was the wind that taught this lesson to her children, the wind that responds every time the children summon it with their whistling.

“It’s coming,” says Yessenia, as the wind rustles quietly in the pines behind the school.

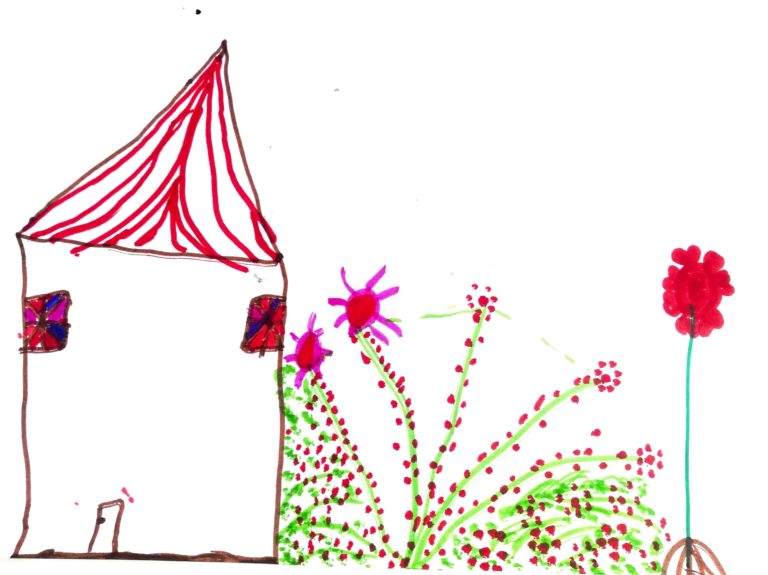

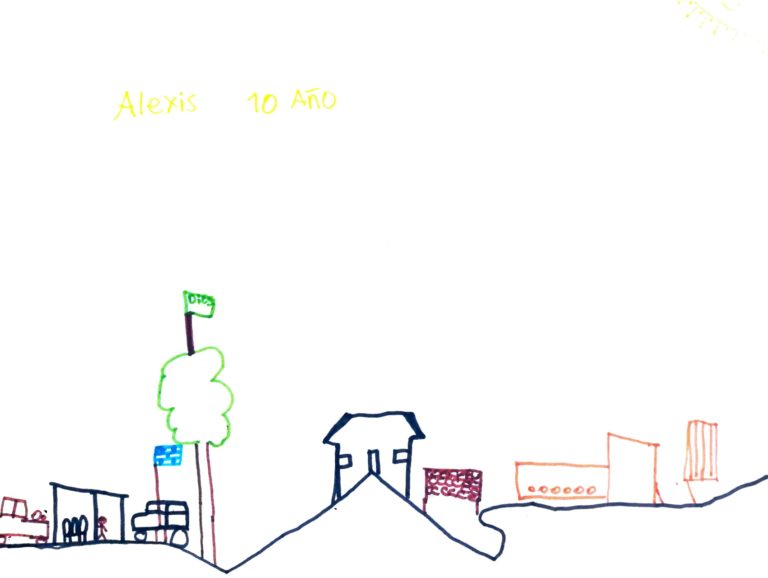

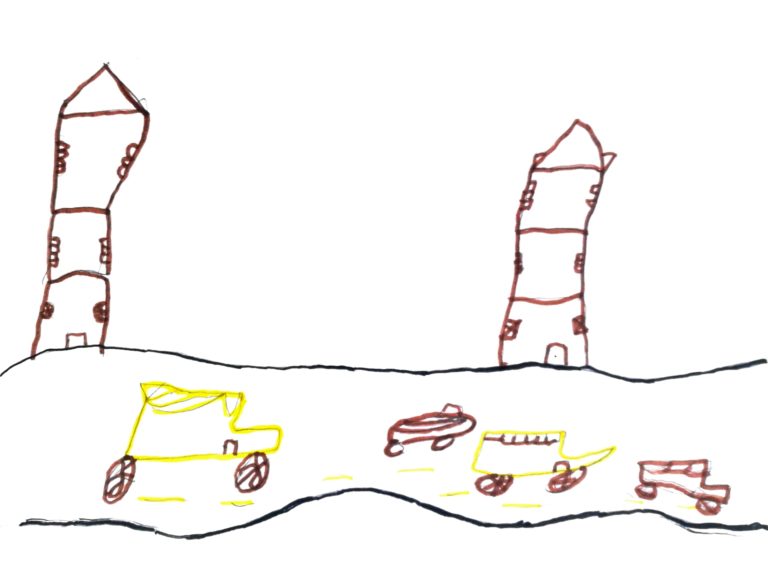

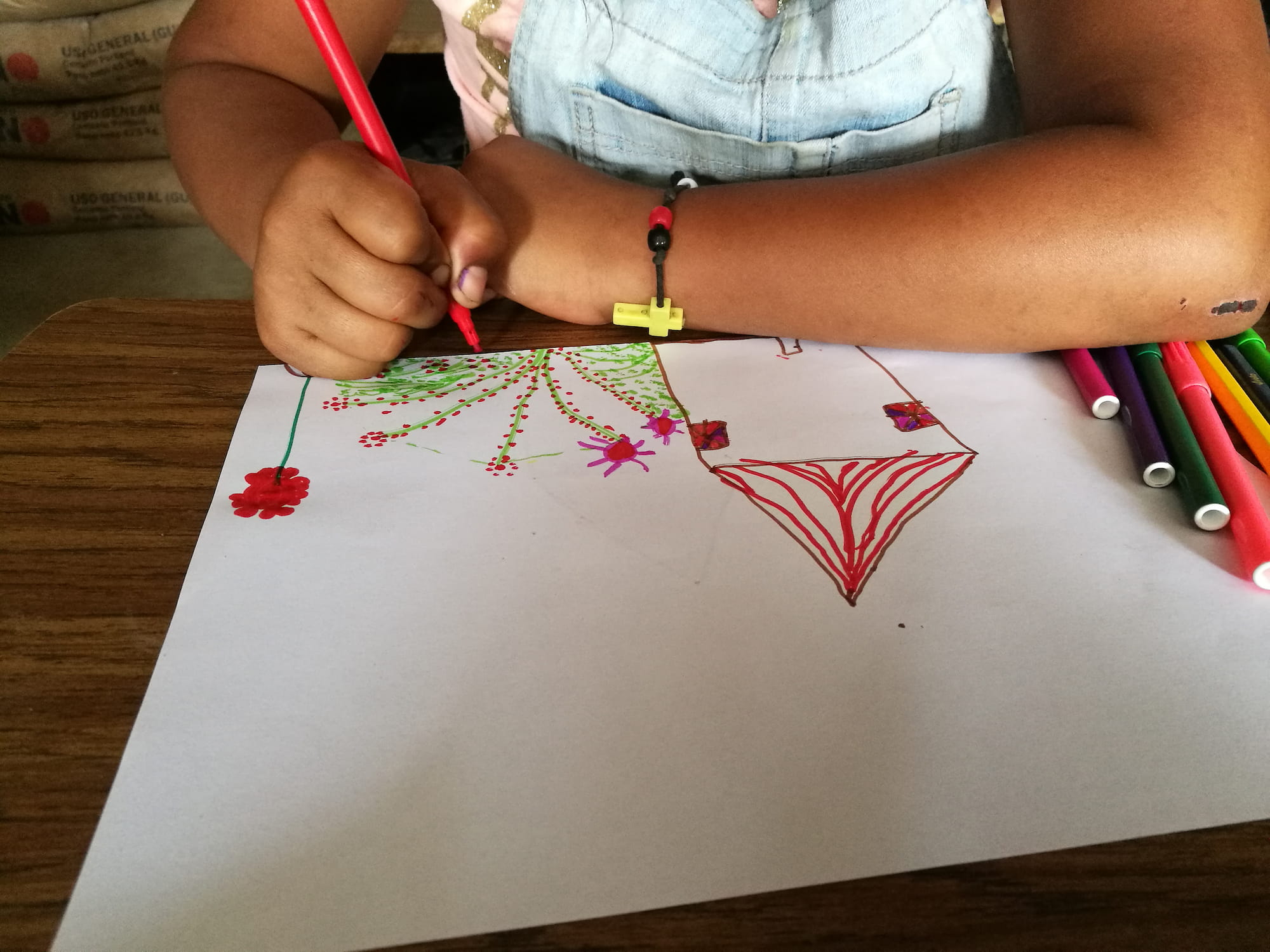

* Note: This story is part of a journalism project called “Drawing My Reality” (Dibujando mi realidad, #NiñezIndígena en América Latina) about Latin America’s Indigenous children. Participants include Indigenous and non-Indigenous children, journalists, and communicators from the Weaving Stories Together Network (Red Tejiendo Historias / Rede Tecendo Histórias). Independent media outlet Agenda Propia is the editorial coordinator for the project.