Daniel Valencia is editor-in-chief of La Prensa Gráfica in El Salvador and coordinator of the Redacción Regional journalism project. Jennifer Ávila Reyes is director of Contracorriente in Honduras. José Luis Pardo Veiras is editorial director of Dromómanos in Mexico.

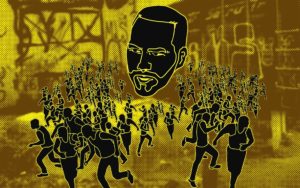

Last week, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) traveled the usual migration route in reverse during a four-day tour of Central America. He visited Guatemala, where his counterpart Alejandro Giammattei has presided over the destruction of the country’s justice system, to the extent that prosecutors are now systematically persecuted. In El Salvador, Nayib Bukele has solidified his grip on the country by extending a state of emergency. In Honduras, Xiomara Castro just completed 100 days as president, an office that she won on the promise to end the criminal behavior of past governments. Yet her family has already interfered in the legislative and judicial branches and has pursued pardons for former officials accused of corruption that served with her husband, former President Manuel Zelaya. AMLO then skipped over Nicaragua, oppressively ruled by Daniel Ortega, and headed for his last stop─ Cuba, seen by some as the oldest dictatorship in the Americas.

AMLO’s objective for this tour was to develop agreements that would slow the massive migrant exodus of recent years through a two-pronged strategy of increasing investment and improving living conditions in the countries of origin. In pursuing this objective, he embraced several representatives of the very authoritarianism that has pushed so many people into exile, with nary a word on the subject.

The Mexican president also turned a blind eye to the daily attacks and threats against journalists and prosecutors in El Salvador, Guatemala, Cuba, and Honduras. At every stop, he and the other presidents asked the United States to make investments in the region. But in exchange for this investment, the United States will demand that these countries take concrete steps to combat corruption, respect the rule of law, and ensure judicial and fiscal independence.

Like his immigration policy, President López’s view of Central America is colored by many contradictions. During his early days in office, he promised independence from the United States, welcomed the first massive migrant caravan of his administration, and even announced a work visa program for migrants. Yet he later erected walls of soldiers along Mexico’s borders. In 2021, a military force of 20,000 was stationed along the northern and southern borders to “protect” Central American children.

During his tour, AMLO boasted about two of his flagship social programs: Sowing the Seeds of Life (Sembrando Vida) and Youth Building the Future (Jóvenes Construyendo el Futuro). In Tegucigalpa, he was greeted by a large banner that read, “Honduras welcomes our friend, Andrés Manuel, and thanks you for the Sowing the Seeds of Life program.” But in Mexico, these programs have cast more darkness than light.

Sowing the Seeds of Life is touted by the Mexican government as the “most important reforestation program in the world.” It seeks to foster rural development but instead has led to widespread deforestation. The Youth Building the Future program is designed to connect job opportunities and unemployed youth who are paid through government-funded scholarships. But in several municipalities, the reported scholarship recipients exceed the number of unemployed youth. Moreover, the program is absent in many areas with the highest unemployment, and some scholarship recipients have displaced full-time employees.

These two Mexican social programs have been implemented in countries like El Salvador, whose own governments openly encourage their citizens to emigrate. During AMLO’s visit, Salvadoran president Bukele told him, “We know that we need to solve the migration issue. It’s best for our people to stay here─ we don’t want productive, hardworking people seeking prosperity abroad.” Yet just a few weeks earlier, Ernesto Castro, the president of El Salvador’s Legislative Assembly and a Bukele crony said, “Give the [journalists] asylum, they can get out of here.”

Climate change, violence, economic insecurity, and now authoritarianism have turned Central America into an efficient, migrant-producing machine. These factors have caused the number of Central American refugees and asylum seekers to skyrocket by 70% in the last five years (41,851 in 2016 to 296,863 in 2021). More than 200,000 people have fled Daniel Ortega’s repression in Nicaragua.

The United States has been trying to turn Mexico into a retaining wall for migrants since 2014. That’s when Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto and U.S. President Barack Obama jointly agreed to implement the Southern Border Plan, causing migrant detentions in Mexico to double in just one year. Anti-immigrant sentiment intensified when Donald Trump became president. The Trump administration implemented its Migrant Protection Protocols and Title 42 policy, both of which made it more difficult for migrants to enter and remain in the United States.

With so many people fleeing their home countries to a destination that’s locking its doors even more tightly, Mexico has gone from being a waystation to becoming the final stop for many migrants. In 2021, a record number of migrants (131,000) applied for refugee status in Mexico, 220% more than in 2020, putting the country in third place for refugee applications behind the United States and Germany.

As immigration overwhelms governments and migrant shelters, and U.S. courts continue to block President Biden’s efforts to repeal Title 42, Mexico does well to seek solutions south of its borders. But exporting ineffective social programs and forging alliances with anti-democratic governments that attack their own citizens will not stem the staggering Central American exodus.

A few days after returning home from his Central American tour, AMLO stated that he would not attend the next Summit of the Americas if the United States vetoes the participation of Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela. While he is right to attribute partial responsibility for the migration crisis to the U.S., he should not ignore the problems that plague Mexico’s neighbors to the south. Many people who leave those countries are fleeing repression by the same presidents AMLO has embraced.

*This editorial is by República Finquera, a journalism project focused on authoritarianism in Central America and Mexico, which is part of Redacción Regional, a media and journalism alliance that includes Contracorriente.