By: Martín Cálix

Translated by Emma Beaver

Approximately 350 families from the sector of Chamelecón are seeking refuge underneath a bridge; shelters are not an option. The families hope to avoid both flooding and the violence of the gangs who control their community. The Honduran state has not been able to guarantee their security amidst the two tropical storms that destroyed their homes. Now, they calculate that the reconstruction will take a year if the government does not allocate resources for their repair.

Twice, the Chamelecón river has inundated and destroyed the neighborhoods that sit on its banks in the sector that bears its name. Chamelecón is one of the epicenters of violence in San Pedro Sula, a city that has the second highest number of homicides in the country— 438 in 2019, according to Sepol. In addition to the gangs and their permanent war for control of the territory, the sector of Chamelecón has also been met with the inclemency of two tropical storms that have destroyed everything in its wake in a number of days.

On the shores of the river, 1500 live among the mud; the sand, pulled loose by flood’s current; the stalled water beginning to smell from the putrefaction. In Chamelecón, one walks through destruction.

Roxy is a 25-year-old trans woman who, along with her family, lost everything in the flood. Accompanied by her 24-year-old friend Fernando, they surveyed what possessions could be saved from her house. Roxy and Fernando didn’t only lose everything in the area where they were born and grew up; they also know that the rebuilding of their neighborhoods will have to be done by the people who live there, without the help of the government. In Chamelecón help never arrives, they said, walking among the remains of what used to be their neighborhood.

For a trans woman, growing up in a place like Chamelecón is to grow up invisible among the invisible. Homophobia and transphobia manifest in jokes and teasing that at first appear as friendship, or a false acceptance, but it’s one that Roxy and Fernando have normalized in order to be able to survive.

When the river rose, they fled, leaving everything behind, including a life represented by a few material belongings that now do not exist. Roxy also lost contact with an aunt in the middle of the disaster, and she doesn’t know if she’s dead or alive. Before the hurricanes, Fernando only lived with his two grandparents, of whom he took care. But now that he has had to move them out of the neighborhood, he has to sleep some nights under a bridge with other people from his sector. Roxy and Fernando have not received help from any state organizations or institutions, nor any LGBTI organizations, they asserted.

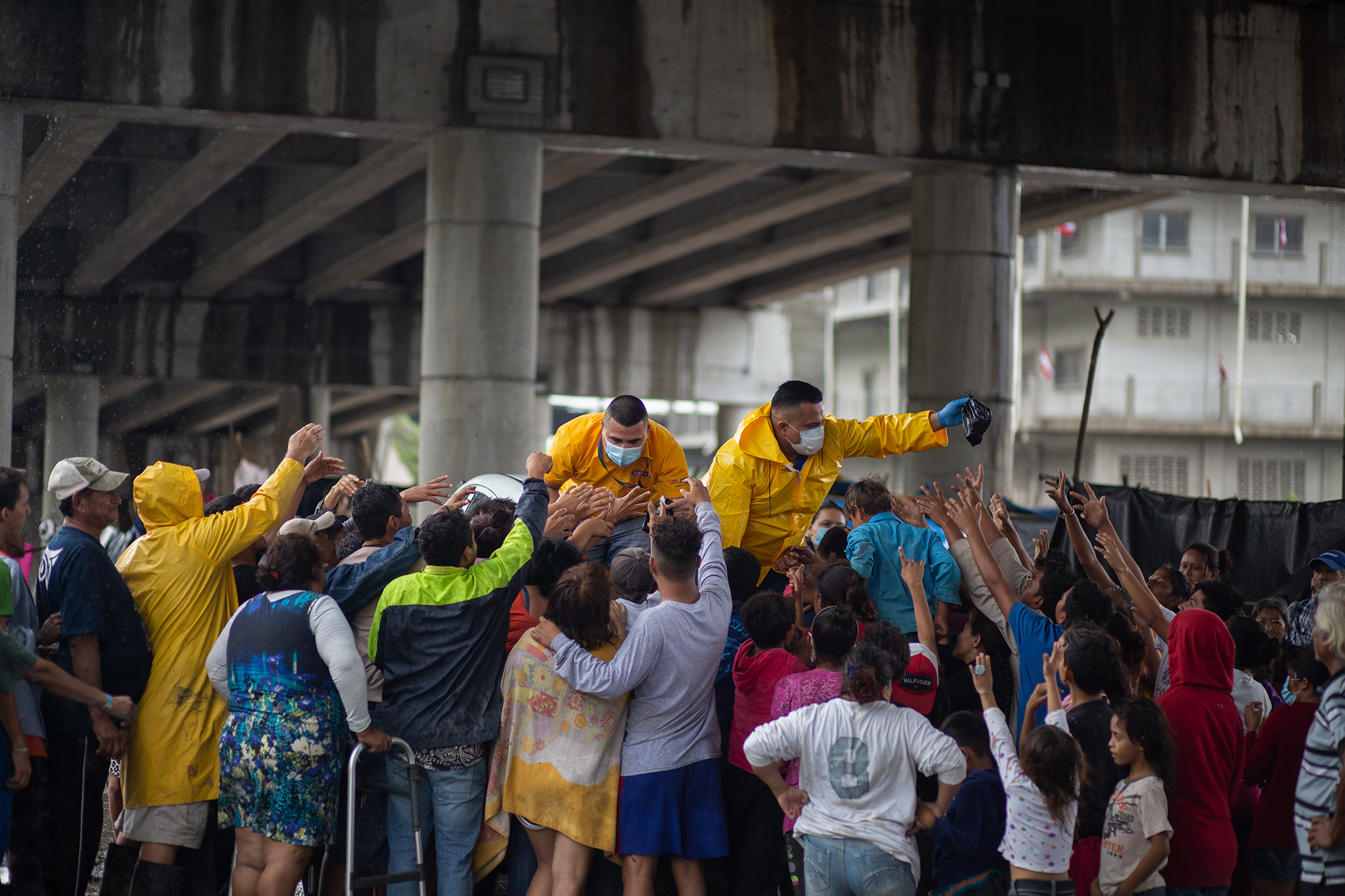

Under the bridge that leads from the city of San Pedro Sula to the exit to the center and west of the country, are at least 350 families. They are there because of tropical storm Eta, which caused the Chamelecon river to overflow and flooded their homes. Before tropical storm Iota came to top off the devastation, many of these families had intended to clean their houses and return to live in them. This is no longer an option.

Despite the cold, hunger and conditions that seem insurmountable, they settled under this bridge. The one shelter set up in their area does not have the capacity to provide refuge to all of the families from this part of Chamelecón. The rest of the shelters are in the territory of the opposing gang where they are not able to go due to violence.

Being homeless makes people forget about the pandemic because there are other problems to be solved, Santos España, an old man seeking refuge under a bridge near his community, said.

Those who live on the banks of the Chamelecón have decided to remain outdoors because they distrust the military — the only presence of the Honduran state under this bridge — and the few institutions attending to the tropical storm emergencies. Living outdoors is the least among a long list of evils that afflict them.

In Chamelecón even the headquarters of the Honduran Red Cross has been converted into a shelter where the 24 volunteers and their families are staying, also affected by the storms. Odalma Henriquez of the Red Cross in Chamelecón said they haven’t received enough supplies to attend to the affected families from the 60 neighborhoods that were wiped out by the floods. This is also the reason they are not able to continue testing for COVID-19, though Copeco insists that testing is part of all shelters’ protocols during the emergency spurred by the two tropical storms.

The families of Chamelecón hope that the water recedes so they can return to their homes and rebuild their lives. This reconstruction will be faced alone; no one from the government ever comes to Chamelecón, said those living under the bridge

While the families of Chamelecón wait for conditions to improve, in the Valley of Sula, it continues to rain. The banks of the rivers are beginning to rise, putting ideas of reconstruction on hold because the neighborhoods are going to flood. Sadness and tears are all the residents have had since Eta drowned their homes a little more than two weeks ago. These neighborhoods have survived the violence of gangs, the violence of the government’s absence, the COVID-19 pandemic and now, the hunger and the cold, in conditions of absolute adversity.