Despite strict measures by the Honduran government, gangs have been taking more territory each year. Could these criminal structures be dismantled by seizing guns and drugs? Are micro and large-scale trafficking the only reasons behind territorial conflicts?

Text and photography: Fritz Pinnow

Valeria Solis contributed to this report

Jason, a member of the Barrio 18 gang, entered a small, dim room and sat on a sofa facing his homeboys. A spontaneous chattering was suddenly heard on a radio: “Guys, we’re leaving Paris and heading to Germany [. . .]. Everything is in order here. Everything is in order! [. . .] Shots fired! Shots fired on the other side!”

Those are Jason’s spotters informing him of every development taking place in La Planeta, a neighborhood controlled by Barrio 18 and one of the most marginalized and poverty-stricken in northern Honduras.

“Take my word for it; the moment you enter our neighborhood, we already know what car you are driving, where you are going, and with whom you are going to meet. You won’t see any of our spotters, but they always see you,” said Mario, a hitman from Jason’s clique.

Since the 1990s, policies and operations, both national and international, have been aimed at tackling gangs in the Northern Triangle as a public enemy, but these criminal groups have increasingly taken over more territory, especially marginalized urban areas.

MS-13 and Barrio 18 are the largest and most notorious gangs that emerged after the massive deportation of gang members from Los Angeles, their place of origin, to Central America.

In 2012, San Pedro Sula, Honduras’ second largest city, had the highest homicide rate in the world, earning the notorious title of “murder capital.” But the homicide rate has significantly decreased and reached the lowest point since 2004. However, the population still perceives that violence is prevalent, and gangs’ control over a large number of neighborhoods remains.

According to a study carried out by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in Honduras, in 2022, extortion increased by 153 percent compared to the previous year, the second highest number in a decade. Sixty-two percent of the 1,824 complaints came from the Central District and San Pedro Sula, the two cities with the strongest gang influence in the country.

Furthermore, the sudden success of Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele, who waged war against gangs, has put pressure on the Honduran government to follow in his footsteps.

This led to the three-phase operation Solution against Crime (Plan Solución contra el Crimen). One of its most important measures is the state of emergency, which suspends Hondurans’ constitutional rights, allowing warrantless arrests and seizing of property.

Mario Fu, spokesperson for the Police Directorate against Gangs and Organized Crime (Dipampco), said one of their main goals under this plan is to bring police officers into communities that have been classified as dangerous because of gang-related crime.

According to Fu, Dipampco’s most important work in the fight against organized crime is to gather intelligence, which helps them identify “hot spots.”

“We are gathering intelligence and conducting investigations in those areas to find and arrest individuals charged with extortion, drug trafficking, murder, forced displacement, criminal association, money laundering, and others.”

Fu explained that gangs’ efforts to control territories are owed to their need to distribute and sell drugs, a “catalyst for violence.” However, he doesn’t discard extortion as an integral activity of gangs.

“It is uncommon for a gang member who sells drugs to not commit extortion [. . .]. As a general rule, if they commit extortion, they are likely to sell drugs and carry out murders for hire,” Fu said.

In line with “iron fist” policies against gangs, in June 2024, President Castro announced on a nationwide broadcast the deployment of security forces, ordering “interventions in parts of the country with the highest gang-related crime rates – that includes murder for hire, drug and weapons trafficking, extortion, kidnapping, and money laundering.”

Historically, micro-trafficking has been a major source of income for gangs and supposedly a way to consolidate power. According to a report by the National Police from mid-2023, the success of the state of emergency is due in part to the seizure of 4,895 pounds of marijuana, 475 kilos of cocaine, 17,633 kilos of crack, as well as 1,373 vehicles and 6,441 motorcycles allegedly used to sell the drugs.

But those figures are a small percentage compared to the amount of tons that Honduran cartels traffic internationally.

In Honduras, drug trafficking generates close to $700 million a year, 4 percent of the GDP, according to data published by Insight Crime in 2016.

According to the Honduran government, drug trafficking is one of the reasons behind the violence perpetrated by gangs.

Barrio 18 and MS-13 gang members have revealed that the seizure of guns and drugs doesn’t address the root cause of gangs’ control over marginalized areas of the country.

In an interview with Insight Crime, the notorious MS-13 leader Alexander Mendoza, aka “Porky,” gave an account of the gang’s evolution into a structured mafia with multiple sources of income, including selling and trafficking drugs. However, he said that a gang like MS-13 cannot completely depend on drugs and that “earning the trust of businesses in areas where they operate” is at the core of their expansion.

The war on drugs is not enough

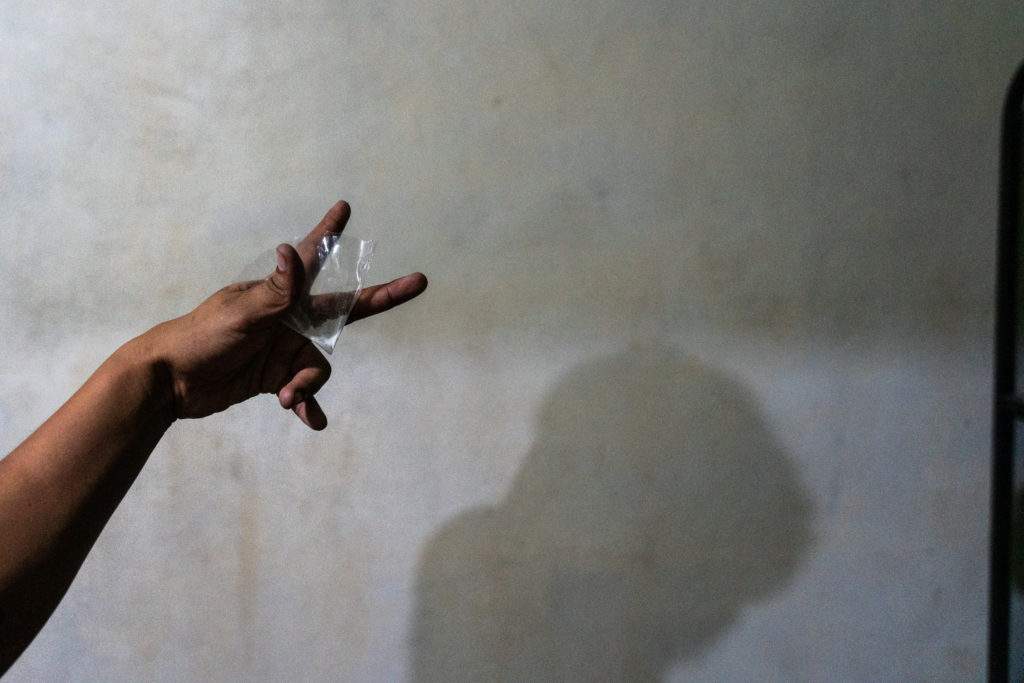

Frederick, a member of Barrio 18, grinned and shrugged his shoulders: “We don’t make a lot of money by selling drugs. This gram of cocaine costs only 100 lempiras ($4). Keep in mind that we sell drugs to poor people. [. . .] Most of our money comes from extortion, which is by far a major source of income.” Businesses in areas controlled by the gang pay the so-called “war tax” or extortion – a fee for being allowed to run a business in gang-controlled territory.

He says the key to charging this fee is to have absolute control over the area. “We have complete control over this area,” said Mario, who presents himself as a Barrio 18 hitman.

“If someone steals, rapes or rats, we kill them. That’s why you could leave your phone anywhere and no one would steal it. People leave keys on their motorcycles and don’t lock the doors of their homes. We don’t just kill because we can. There has to be a reason, and processes have to be followed.”

This has led to the community relying on gangs to solve internal problems. “The boys are the government here,” said Giovani, a resident of the La Planeta neighborhood. “The land where I built my house is not officially registered to me, but I’ve been living here for 24 years.” He came to the district a long time ago looking for new opportunities in the city. A man claimed to own the land and charged large sums of money to the community to live there. “He had a friend in the mayor’s office and was able to exploit us for what little we had. His bodyguards killed 12 people during the dispute, and we begged the government to help us, but nobody listens to the poor around here.”

The dispute culminated in the murder of the owner, Miguel Carrión, and his two bodyguards in downtown San Pedro Sula, but the property deeds were never issued to the community, Giovani said.

“The boys [gang members] at least acknowledge that this property belongs to me, and I can count on them for protection from rival gangs who come here. The police don’t dare come here, and if they do, they damage property, harass locals and then leave.”

Giovani is one of the few people who has lived in an area known as the invisible border, a division between La Planeta, which is controlled by Barrio 18, and the Rivera Hernández district, which is controlled by MS-13 and other small gangs.

The invisible borders are “hot spots” where abandoned houses usually stand and rival gang members constantly try to infiltrate to obtain intelligence.

“Where there’s an invisible border, there’s gunfire!” said Mario. “There are many shootings in the area. We recently captured two MS-13 members who were snooping around [. . .]. After capturing them, we torture them for information, and if we get what we want, we make them disappear. It’s that simple.”

According to Jason, a leader of Barrio 18, every gang has undergone a significant transformation. “It’s no longer smart to be violent and kill people on the streets. We are more than that now. We focus on gathering intelligence and maintaining better control over the area [. . .]. If the police come and seize our guns and drugs, we don’t resist. If they take one of our boys, we are usually able to buy their freedom. That’s how the police make extra money.”

Jason’s account reveals that the National Police capture gang members and demand a ransom to relatives for their freedom. Such negotiations and corruption are not sporadic or exclusive to territories controlled by Barrio 18, said María, who carries out murders for the MS-13 gang. “The police sometimes come and take one of our boys, so we have to buy their freedom. But we have people in the police.”

María explained that MS-13 has evolved and is now focused on consolidating power in its territories by gathering more intelligence and establishing a closer relationship with the police.

Drugs also play a secondary role in MS-13-controlled territories, where violence is a recourse to consolidate power, not to fight for the opportunity of selling drugs.

“We sell different kinds of cocaine that cost between 200 lempiras ($8) and 400 lempiras ($16). In addition, we have our own special brand of marijuana called tiburón, which is more potent.” It is more expensive and only small amounts are sold.

None of the gangs are deeply worried about Phase III of the government plan, which is supposed to be carried out soon.

“They have done this before but always leave in the end. We’ll probably just wait for it to pass. One of our bosses always bribes one of theirs,” said María.

Jason has a similar opinion: “If the police come, we don’t confront them. They can kill us without repercussions. If one of us kills a police officer, they come at us with everything and kill everyone, including the family of that person, even their grandparents.”

But Jason explained that it is not necessary to confront the police while they carry out raids because people from the area do not trust them: “No one is going to help them [the police] because they don’t solve any problems or take responsibility for the neighborhood. We are the only ones who do.”

Conversations with Barrio 18 and MS-13 gang members revealed that by seizing drugs and weapons, authorities are not addressing the root causes of gangs’ control over marginalized neighborhoods.

Although some members of MS-13 traffic drugs on a large scale, drug consumption in neighborhoods remains a source of income for gangs who control them.

However, according to gang members and residents, gangs maintain control through violent governance, and the absolute authority over neighborhoods is owed to the constant marginalization and lack of trust in the police and armed forces.

The government’s new plan to deal with gangs and organized crime is a war on drugs. But gangs are fighting for territorial sovereignty, a way of surviving current aggressive policies aimed at taking away their control of neighborhoods.

The names of persons interviewed for this article have been changed to protect their identities.