On December 9, 2021, on a highway in the Mexican state of Chiapas, a trailer truck overturned. It was transporting about 200 people traveling towards the American dream; 56 of them died. Investigating this tragedy, a cross-border journalistic alliance uncovered the story of how organized criminals charge migrants exorbitant fares to stuff them, like merchandise, into these steel boxes leaving a long trail of corruption in their wake. The central corridor of Chiapas, with two main border crossings, is the preferred route for this brutal trafficking of people in trailer trucks. Thousands of migrants from more than twenty countries have traveled north like ghosts. And only when they have accidents or die, they become visible.

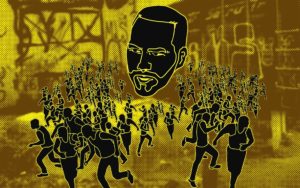

By Ángeles Mariscal (Chiapas Paralelo), María Teresa Ronderos (CLIP), Jody García (Plaza Pública and Brenda Medina (ICIJ). Ilustración: Alejandra Saavedra Lopez

Guatemalan survivors of the accident that occurred in Chiapas, Mexico, on December 9, 2021 identified the “Chiapanecos” as the people who came to their communities to offer them transportation services to the United States. Chiapanecos also coordinated their truck trip, which made national news for its fatal toll of 56 people dead and 113 injured. Other victims testified that they heard them speaking in an indigenous language.

The witnesses, perhaps unknowingly, were pointing to the Chamula Cartel, composed mainly of Tzotzil indigenous people from the town of San Juan de Chamula in the highlands of Chiapas. This cartel controls migration along the central corridor of that state on the border with Guatemala. This was confirmed by Jorge L., a former federal officer with expertise in migration, who chose not to reveal his name. The government had only recognized Chamula as a criminal group in November 2021, shortly before the December 9 accident.

Since the 1990s, many Tzotzil people from Chamula had come to know the routes through experience, as they themselves were among the largest communities of migrants to the United States. At the time, they were the group with the most deportees from that country.

“If you managed to get to the United States as an indigenous Tzotzil Chamula, of course you returned to your community and wanted to take more family with you; then a dynamic began, as a moral, ethical thing, so to speak, of sharing the wealth,” said another expert in this region who chose not to reveal his name for safety reasons. Later, he explains, other people began to pay that person, “and this began to generate this story of the polleros (traffickers) of Chamula, but the beginning has more to do with an exchange and with strengthening the community itself.”

After President Felipe Calderon’s administration declared war on organized crime in 2006, dozens of drug traffickers took their families to quieter areas of the country where they could protect them, Chiapas among them.

Sinaloa Cartel arrived from the north and “came up against the strong sense of community and control of the Chamula territory (…) ‘Here we are the cartel’, the Chamula said, and they agreed on the conditions of passage,” explained Jorge L., adding that with support from the national cartel, the Chamula gained in infrastructure and strength.

Their client base also grew enormously. Central Americans were leaving their countries en masse after the economic devastation caused by Hurricane Mitch in 1998. Other waves followed, driven by poverty, climate change and violence. To contain them, U.S. and Mexican policies tightened. Later, republicans – under President Donald Trump – put migration control and xenophobia at the center of their programs.

Crossing the previously symbolic border between Chiapas and Guatemala, which had come into existence in 1824 when Chiapas ceased to be part of the Capitanía General de Guatemala, became difficult, as did traversing Mexico towards the United States. And as the road grew harder, prices increased. Once a part of community life, traffickers started seeing the transportation of people as a lucrative business.

Crossing had been a gesture of solidarity among Tzotzil people helping each other navigate a flexible and porous border in cars or small trucks; now it had become a semi-industrialized trade with trailer trucks and mainly through the central corridor.

According to records sent by the National Migration Institute (INM) in response to requests for information made by this journalistic team, each trailer carries hundreds of people. One registered at the end of 2021, carried 468 migrants. With so many human beings crammed together, some standing with nowhere to grab onto, any jolt or mechanical failure can result in death. It is a deathtrap.

A recent occurrence revealed that the Chamula force now controls the smuggling of migrants in this border corridor. According to press reports, on March 2, people from Betania blocked the highway to Tuxtla Gutierrez in protest, claiming that neighboring residents had detained three men from their community. The neighbors announced they were in fact holding the men from Betania because they were armed and were using their territory as a passageway for smuggling migrants.

However, documents from the Secretary of National Defense (Sedena) leaked by Guacamaya reveal that in recent years there have been other groups disputing migrant smuggling along the border. The Jalisco Cartel – New Generation (CJNG) and even members of Salvadoran gangs have a presence in Tuxtla Gutierrez, the capital of Chiapas, and in San Cristobal, the state’s most touristic city. In 2023, in that state, armed disputes between the CJNG and the Sinaloa Cartel nearly quadrupled compared to 2022, as reported by the ACLED project, which tracks data on armed conflict around the world.

These are some of the findings of the cross-border investigation carried out by Noticias Telemundo, the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (CLIP), Pie de Página and its allies Chiapas Paralelo in Chiapas, En un 2×3 in Tamaulipas and journalists in Veracruz, Contracorriente in Honduras, Plaza Pública in Guatemala, ICIJ for the Dominican Republic and Bellingcat.

After nearly 25 interviews with experts and authorities, multiple requests for information through transparency laws, searches in open sources and reporting with main actors and migrants in Mexico, the United States, Guatemala and the Dominican Republic, this alliance established another cause for the boom in human trafficking in trailer trucks. Namely, the existence of criminal networks articulated in a sophisticated and transnational manner, and taking advantage of the voluminous transportation of merchandise that takes place between Mexico and Central America in this type of trucks. This is detailed in the main story of this investigation.

The present story focuses on the border region between Guatemala and the state of Chiapas. Through the Ciudad Hidalgo customs office in southern Chiapas alone, 128,000 cargo vehicles crossed in 2016, according to Mexico’s SAT. Upon entering Mexico on the way back, a few of these trucks are loaded with containers to carry migrants determined to make a new life for themselves in the United States.

In almost five years (between 2019 and September 2023) the INM has found 21 trailers going through Chiapas, either due to random searches or because they were left stranded or had accidents. In them, 3,356 men, women and children were being transported. They came mainly from Central America, but also from Ecuador, Haiti, Cuba, Dominican Republic, India, and Bangladesh, among other nationalities.

The INM told this journalistic team that 80 of these migrants died in Chiapas. The figure may be underreported because a database constructed by our team with public reports from the INM itself and press releases yields a lower number of migrants found but a higher number of dead. Our database records that at least 101 people died in Chiapas alone, between October 2018 and November 2023, while trying to cross Mexico in trailers.

The accident

Sitting on the terrace of her house in Cañafistol, a town of 8,000 inhabitants in the province of Peravia, in the Dominican Republic, Dulce Soto, mother of six children and grandmother of Yuniel Baez, told that she and her daughter-in-law spent those days in December glued to the TV and to their phones checking videos and WhatsApp groups, waiting for news of the accident in Chiapas. After a second day with no news from Yuniel, she and her grandson’s girlfriend saw in a video his body lying on the pavement, wearing orange striped pants. “That’s Yuniel, that’s him!”, said Dulce and the girlfriend nodded. The boy was 23 years old. They embraced in tears.

The tragedy happened at 3:23 pm on December 9, 2021, some 140 miles inside Mexico’s border with Guatemala. The trailer truck had passed three minutes earlier through the toll booth at Chiapas de Corzo, on the road that leads to Tuxtla Gutiérrez, capital of Chiapas. The driver of the trailer truck -who was driving with “flushed cheeks and dilated eyes”, as one of the survivors described him – took a curve at over 60 mph and overturned. Dozens of people who had been hiding in its box flew out. Eleven Dominicans died, almost all of them from the same part of the island as Yuniel, and 42 Guatemalans, according to the authorities of those countries.

“I raised him like a son, the only thing I had left of my own son,” Dulce told the journalist of this alliance who visited her at her home in April 2023. Yuniel’s father had died at the age of 21 on his way to Puerto Rico on a raft. He disappeared at sea. “He came and handed me his son with a little bed and even a bedsheet and said, ‘take care of him until I come back’.”

Yuniel’s body arrived in the village on December 24. They also returned the corpse of a neighbor on December 25. “Imagine, it was sad, a wake here and a wake there,” said Dulce. She consoles herself with the fact that “at least I have him (Yuniel) here and I can go see him, but my son was swallowed by the sea, I never heard from him.” Two of her other children have already left for the United States through Puerto Rico or Mexico.

Yuniel’s cousin was injured in the accident and was sent back to the Dominican Republic. He stayed there until his broken bones healed. A few months later he made his way back to the United States through Mexico and this time, he made it. They say he is in New York.

In the village of Xenimaquin, municipality of Comalapa, department of Chimaltenango, in Guatemala, lives Paulino Quirá, who lost his 19-year-old son Marcos Gabriel in the accident. He contacted him, the fourth of his eleven children, the day before. Marcos told him that he was in San Cristobal de las Casas in Chiapas and that they would be leaving town the next day. He was in a hurry. He didn’t know when they were going to take him, and he wanted to leave. “I told him stay on it, don’t be ashamed, they (the coyotes) know the trip, they are the ones driving,” Paulino told a journalist from this alliance who visited him at his home in Xenimaquin.

“We always all have something to wish for,” said Paulino, “here you don’t really achieve anything. We have seen that those who go to the other side have always achieved something, that’s why he decided to leave, but unfortunately, he didn’t realize his dream. He wanted to build a house and buy land to farm. I am a farmer and he wanted that too.”

Paulino said that on Friday, the day after the accident, his daughter-in-law called him and told him that there had been an accident, and asked if Marcos might have been in it. He answered: “We hope to God no.” Then he continued his story: “In the afternoon I added internet credit on the phone and there I saw that many photos came out and I recognized that he was there, because of his haircut and a little of the profile of his face.”

Even today, two years after the accident, it is still unknown how many passengers were with Marcos, Yuniel, and his cousin. In an interview with the Mexican National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) that investigated the case, a copy of which we could access, one survivor said that about 300 people were on board. Another said he heard the organizer say that there were 210 travelers in the trailer.

When the relief corps arrived at the scene of the accident, they saw many of the surviving passengers leaving. INM official records -obtained using transparency law for this investigation- registered only 111 travelers, although the CNDH found a much higher number: just those affected were 169.

According to information the Guatemalana Ministry of Foreign Affairs gave to this investigation, 143 citizens of that country came in the container. The CNDH said in its report that there were 148 Guatemalans, and that among dead and injured there were 16 from the Dominican Republic, three from Ecuador, one from El Salvador and a young man from Colombia, later signalled by the prosecutor’s office as a possible member of the trafficking gang.

“We had hoped to give our families something better, that’s why we left (…) now with the accident, what are we going to return to the community with?”, 32-year-old Florentín Yatpop told Chiapas Paralelo, an ally of this investigation, hours after the rollover. He is a day laborer from Izabl, Guatemala, who lost his friend Santiago Bolom, 46, in the accident.

Yatpop was praying at a health center where he was recovering from his injuries when journalists approached him. “They (the traffickers) told us that we were going to go in some buses, not in trailers. When it took the curves we had nowhere to hold on. When it crashed, those who were standing up got hit harder, they hit their heads, I think that’s why so many people died.”

Dulce’s grandson Yuniel called her every one of the six days of travel before the accident. He told her he had flown from the Dominican Republic to another country before entering Mexico by land. The grandmother did not know which country.

Paulino traveled to Mexico to look for his son’s body. He inquired at the hospitals and the Red Cross gave him a list of the deceased, but his son was not listed. In the end, and after walking him through many offices, they did a DNA test and confirmed that his son was among the dead.

“The only ones who lent us a hand in Mexico were some journalists and other people who were also looking for their relatives, we had to walk a long way and then they told me to go back to my house.” The mayor of Xenimaquin promised to send Marcos’ body. About ten days later it arrived.

Florentín Yatpop, and another survivor – this one a minor – said that they were taken from their places of origin by public transport to the border crossing between Chiapas and Guatemala, known as La Mesilla – Ciudad Cuauhtémoc; others crossed through the Carmen Xhán community, a little further north. In all cases, they arrived at a town where, as one of them said, “there was a large embankment, there were several trailers (…) some spoke an indigenous dialect”. There, a first group was loaded onto a trailer, but there were so many migrants that they were loaded onto a second one, which crashed.